It's all about the classical music composers and their works from the last 400 years and much more about music. Hier erfahren Sie alles über die klassischen Komponisten und ihre Meisterwerke der letzten vierhundert Jahre und vieles mehr über Klassische Musik.

Total Pageviews

Tuesday, August 16, 2022

Yuja Wang: Schumann Piano Concerto in A minor Op. 54 [HD]

Monday, August 15, 2022

Love Theme from Romeo and Juliet - Joslin - Henri Mancini, Nino Rota

Love Theme from Romeo and Juliet - Joslin - Henri Mancini, Nino Rota

Manila Symphony Orchestra | Medley of Philippine Folk Songs by Bernard G...

Yuja Wang: Mendelssohn Piano Concerto No. 1 in G minor, Op. 25 [HD]

Friday, August 12, 2022

Reading Franz Liszt: The Poetry Behind the Piano Music

by Frances Wilson, Interlude

In the introduction to his new book, pianist Paul Roberts recounts a conversation with “an elderly and much celebrated piano teacher” when he was just starting out as the inspiration for a lifetime’s fascination with literature and language and the essential connections between literature and music: “I introduced myself. I cannot remember quite how the topic came about, but within a few minutes we were talking about Liszt’s great triptych of piano pieces known as the Petrarch Sonnets, inspired by the love poetry of the 14th-century Italian poet Francesco Petrarca. “Oh!” I enthused, “those poems …!” She entered her studio. “We don’t need them,” she said, and closed the door. I was deflated. And dumbfounded.”

In the introduction to his new book, pianist Paul Roberts recounts a conversation with “an elderly and much celebrated piano teacher” when he was just starting out as the inspiration for a lifetime’s fascination with literature and language and the essential connections between literature and music: “I introduced myself. I cannot remember quite how the topic came about, but within a few minutes we were talking about Liszt’s great triptych of piano pieces known as the Petrarch Sonnets, inspired by the love poetry of the 14th-century Italian poet Francesco Petrarca. “Oh!” I enthused, “those poems …!” She entered her studio. “We don’t need them,” she said, and closed the door. I was deflated. And dumbfounded.”

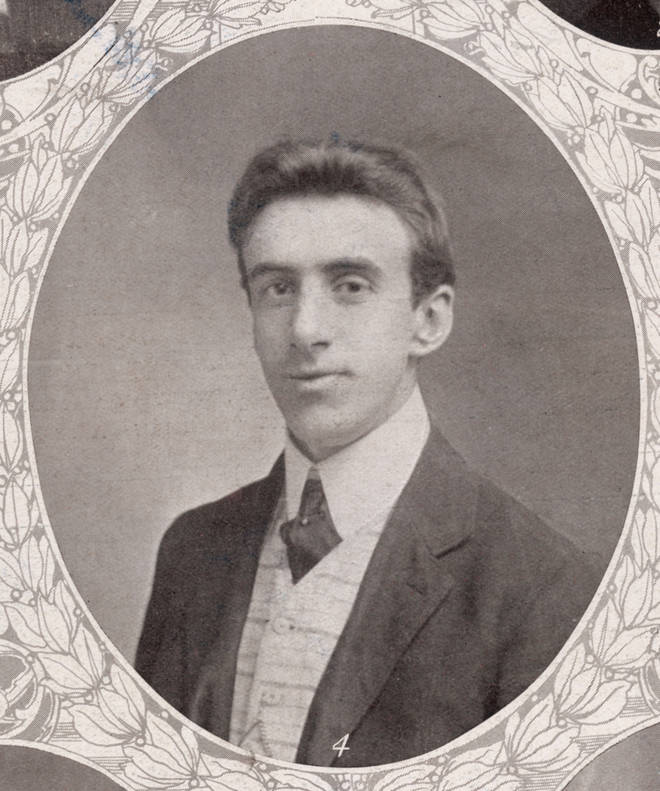

Paul Roberts feels that music comes from sources beyond simply itself – from, for example, the composer’s life experience, the influence of others, and, in the case of Liszt, poetry and literature, and that as pianists we do the music, and its composer, a disservice by not paying attention to these external sources of inspiration. In his engaging, eloquent and highly readable text, Roberts explores what he believes to be an inseparable bond between poetry and the piano music of Franz Liszt, and how literary inquiry affects musical interpretation and performance. For Roberts, an appreciation of the poetry which inspired or informed Liszt’s music gives the pianist, and listener, significant insights into the composer’s creative imagination, bringing one closer to his music and allowing a deeper understanding, and, for the performer, a richer, more multi-dimensional interpretation of the music. It also offers a better appreciation of Liszt the man: too often dismissed as a superficial showman, in this book Roberts reveals Liszt as a man of passionate intellectual and emotional curiosity, who read widely and with immense discernment, all of which is reflected in his music. As Alfred Brendel said, “Liszt’s music….projects the man”.

Paul Roberts © Viktor Erik Emanuel

Poetry and literature were meat and drink to Franz Liszt, who performed in and attended the cultural salons of 1830s Paris where he knew writers such as Victor Hugo and George Sand. He was familiar with the writing of Byron, Sénancour, Goethe, Dante, Petrarch and others, and his scores are littered with literary quotations which offer fascinating glimpses into the breadth of his creative imagination and what that literature meant to him. For the pianist, they provide an opportunity to “live inside his mind” and open “our imaginations to the wonder of his music”.

Perhaps the most obvious connection between Liszt and poetry is his Tre Sonetti del Petrarca – the three Petrarch Sonnets. They began life as songs which Liszt later arranged for piano solo, and included them in the Italian volume of his Années de pèlerinage. Liszt and his lover Marie d’Agoult spent two years in Italy and it was here that Liszt was exposed to the marvels of Italian Renaissance art and architecture and the poetry of Dante and Petrarch.

The poetry of Petrarch was central to Liszt’s creative imagination and in his triptych inspired by the Italian poet’s sonnets, we find an extraordinary depth of expression and emotional breadth. In the chapter ‘The Music of Desire’, Roberts explores Petrarch’s sonnets in detail and demonstrates how Liszt translates the passion of the poet into some of the finest writing for piano by Liszt, or indeed anyone else.

Perhaps because I have studied and performed these pieces myself, a study which included close reference to Petrarch’s poetry, it is here that I find Roberts’ argument most persuasive, that the pianist really needs this literary context and understanding to bring the music fully to life. He shows how Liszt responds to the ebb and flow of emotions in Petrarch’s writing, in particular in the most passionately dramatic of the three sonnets, No. 104, “Pace no trovo” (I find no peace), where the poet veers almost schizophrenically between extremes of emotion, from the depths of despair to ecstasy.

Franz Liszt

Subsequent chapters explore other great piano works – the extraordinary B-minor Sonata which Roberts believes is firmly connected to that pinnacle of nineteenth century European literature, Goethe’s Faust, the existentialism of Vallée d’Obermann, a work which exemplifies the Romantic spirit, and its relationship with Etienne de Sénancour’s cult novel Obermann, the “aura” of Byron and his Childe Harold’s Pilgrimage which pervade the Swiss volume of the Années alongside Liszt’s personal experience of the majestic landscape of Switzerland and the Alps. The final chapter explores the Dante Sonata and Liszt’s reverence for The Divine Comedy at a time when Dante’s poetry was being rediscovered by English and European Romantic writers like Keats, Coleridge, Shelley and Stendhal. Throughout, Roberts conveys the power of literature to awaken and inspire the Romantic imagination and sensibilities, and demonstrates how this might inform the way one performs Liszt’s music – from the physical cadence of poetry to its drama, narrative arc and emotional impact which had such a profound effect on Liszt and which infuses his music in almost every note. Here Liszt finds a new kind of expression in which, in his own words, music becomes “a poetic language, one that, better than poetry itself perhaps, more readily expresses everything in us that transcends the commonplace, everything that eludes analysis”.

A useful Appendix explores the influence of other poets such as Alphonse de Lamartine and Lenau, with analysis of other pianos works, including Bénédiction de Dieu dans la solitude, the Mephisto Waltz, the two St Francis legends, and Mazeppa, inspired by a poem by Victor Hugo.

In this book, Paul Roberts reveals the essence of Liszt literary world, providing the pianist with valuable insight and inspiration with which to appreciate, shape and perform his music.

Reading Franz Liszt: Revealing the Poetry behind the Piano Music is published by Amadeus Press, an imprint of Rowman & Littlefield, USA.

Musicians Divulge a Secret: The Pieces They Would Rather Not Play Ever Again!

by Janet Horvath, Interlude

Put Ravel’s Daphnis and Chloe or La Valse, Stravinsky’s Rite of Spring, or Rachmaninoff’s Symphonic Dances—or pretty much anything by Prokofiev or Mahler—in front of me and I’ll play them happily over and over, and I have. But dear readers I must confess there are pieces of music I hope I never have to play again, and I’m not alone. Some works we professionals play to death; others just get under our skin. Let me explain.

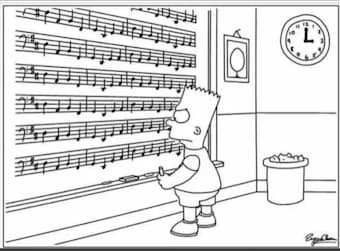

Perhaps you love the Pachelbel Canon. It’s a popular piece for weddings. While the violins soar through multiple variations the poor cellist plays the same 8 notes s-l-o-w-l-y, repeating the pattern D-A-B-F#-G-D-G-A. Each iteration takes 4 measures and is played 28 times! And some perform it extra deliberately. It’s a bit like detention for cellists! Funny enough, once a local National Public Radio classical music radio station played this continuously until they’d met their pledge drive donation goals. I imagine some listeners silently (or loudly) screamed, “Make it stop…”

Crazy instructions!

Ravel’s Bolero is another very popular piece of music but not for the snare drum player. He or she has to play the two-bar 24-note pattern unrelentingly steady in rhythm starting very softly or pianissimo and increasing in volume to a dramatic fortissimo. The piece is 430 bars; about 15 minutes. Need I do the math? That’s 5,144 snare drum strokes. Talk about repetition… And since we’re counting, did you know Tchaikovsky was fond of the cymbals? During Swan Lake, there are a total of 1,214 cymbal crashes in each performance. One of my colleagues sat very close to the percussion section. The din after 21 performances and 29,715 cymbal crashes, left her shell-shocked.

Other pieces can be tiresome because of the ubiquitous numbers of performances of them. One colleague told me, “I had a nightmare that I was playing Messiah, and I woke up and it was true!” Ditto Tchaikovsky Nutcracker. I remember during the Holidays the Minnesota Orchestra would be divided in two. Half played 10 Messiah performances and the other half performed The Nutcracker Ballet 13 times in two weeks—twice on weekend days—every season for years. May I remind you of the temperatures in December in Minnesota that dip well below zero? The nearest parking was several blocks away. I’d drag my cello in the bitter cold to the huge auditorium hoping to thaw in time for the performances.

Other pieces can be tiresome because of the ubiquitous numbers of performances of them. One colleague told me, “I had a nightmare that I was playing Messiah, and I woke up and it was true!” Ditto Tchaikovsky Nutcracker. I remember during the Holidays the Minnesota Orchestra would be divided in two. Half played 10 Messiah performances and the other half performed The Nutcracker Ballet 13 times in two weeks—twice on weekend days—every season for years. May I remind you of the temperatures in December in Minnesota that dip well below zero? The nearest parking was several blocks away. I’d drag my cello in the bitter cold to the huge auditorium hoping to thaw in time for the performances.

There are many works that are ever-present in our repertoire. Sometimes the consequences of often-played repertoire are that they are given short shrift in rehearsal. No musician enjoys walking on eggshells during a concert or conversely slamming through a work such as Liszt Les Preludes, Orff’s Carmina Burana, Tchaikovsky’s Romeo and Juliet or the Symphonies No. 4 or No. 5, or even Handel’s Water Music. There are always tricky passages and difficult transitions that should be rehearsed for ensemble.

There are many works that are ever-present in our repertoire. Sometimes the consequences of often-played repertoire are that they are given short shrift in rehearsal. No musician enjoys walking on eggshells during a concert or conversely slamming through a work such as Liszt Les Preludes, Orff’s Carmina Burana, Tchaikovsky’s Romeo and Juliet or the Symphonies No. 4 or No. 5, or even Handel’s Water Music. There are always tricky passages and difficult transitions that should be rehearsed for ensemble.

Perhaps a particular piece brings back bad memories. Did your mom force you to play Für Elise by Beethoven or Haydn Trumpet Concerto for Aunt Betsy, and Grandma Rose and every person who was invited over for dinner when you were growing up no matter how you protested? My parents were guilty.

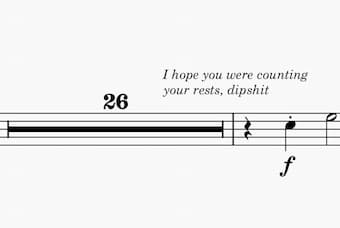

Please don’t blame the poor second violins and violas (and sometimes the horns) when they almost drop their instruments in boredom. While you’re elegantly waltzing, they have to play endless off beats in Strauss waltzes or Sousa Marches, and they rarely get to play the melody.

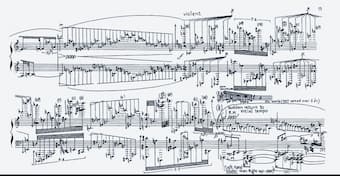

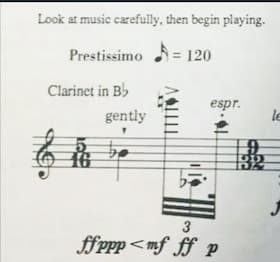

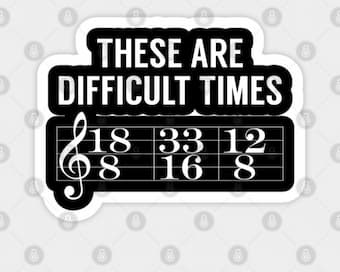

Unplayable!

We really have no patience for a composer who doesn’t know our instrument and writes nothing but rests. We relish performing pieces that are challenging unless the composer’s metronome markings suggest an unplayable tempo, contradictory (or silly) instructions, or if he or she uses an undecipherable meter, like something you’ve seen in a calculus textbook watch out. That’s when we might throw up our hands!

Even soloists must bemoan the fact that certain concertos, favorites and crowd-pleasers, are requested in every city despite the fact that an artist hopes to perform more unfamiliar works worth playing and hearing. But that said, we never tire of the great masterworks: Brahms, Sibelius, Barber, and Mendelssohn Violin Concertos, Brahms, Schumann, Grieg, Rachmaninoff, Prokofiev, and Tchaikovsky Piano Concertos and Beethoven of course.

Pianist Jon Kimura Parker tells us that he first played the Beethoven Third Piano Concerto in C minor, when he was twelve years old. It was his concerto debut in Vancouver, with the Vancouver Symphony and the first concerto he ever learned. This week, the 50th anniversary of performing the work, he still finds new revelations, after playing it countless times. Beethoven’s vehement music continues to speak to us. Surely music wouldn’t be where it is today without him. Listen to this rendition of the last movement of Beethoven’s First Piano Concerto during Covid. “One can only imagine what Beethoven would think of all of this,” says Parker. “That his music is being performed so much even now, when our logistic preparations have required extra imagination, would surely boggle his mind!”

Rather than predictable as some music is, this music never ceases to amaze performers and listeners alike. But even the masterworks of our repertoire benefit from a fresh approach by the artist and/or new ideas from the conductor.

Rather than predictable as some music is, this music never ceases to amaze performers and listeners alike. But even the masterworks of our repertoire benefit from a fresh approach by the artist and/or new ideas from the conductor.

My suggestion for programing a recital, a small ensemble concert, or a full orchestra season: it would be wise for small ensemble artistic directors, orchestra managements, and conductors to consider not only “good box office” but also what will challenge, inspire, and stimulate the musicians. That’s no secret!

Thursday, August 11, 2022

Love is in the Air - Gimnazija Kranj Symphony Orchestra

The 110-year-old Titanic violin that miraculously survived the sinking ship

By Siena Linton, ClassicFM

This violin holds a lifetime of stories in the grain of its wood...

Of all the instruments in the world, violins and other string instruments are often renowned for their longevity, with the centuries-old creations of Italian luthiers, Amati and Stradivari, holding hundreds of years’ worth of stories, and selling for millions of pounds today.

Few, however, can compete with that of the Titanic violin – the instrument played in April 1912, as the RMS Titanic sank into the North Atlantic Ocean after its fatal collision with an iceberg.

Today, the violin is held at the Titanic Museum in Tennessee, as part of their public display of artefacts and memorabilia from the ship.

But the story of how it got there is not quite so simple...

A wedding that never took place

The now-famous violin was crafted in Germany in 1910, and was gifted to Wallace Hartley of Colne, Lancashire, as an engagement present from his new fiancée Maria Robinson. An inscription on the instrument’s tailpiece read, ‘For Wallace, on the occasion of our engagement, from Maria’.

The sweethearts likely met in Leeds, where Hartley played as a musician in various institutions around the city. Having previously provided musical entertainment on the RMS Mauretania, Hartley was contacted shortly before the RMS Titanic departed from Southampton on its maiden voyage with a request that he become its bandleader.

After his initial reluctance at leaving his fiancée, Hartley agreed to join the transatlantic crossing, hoping to secure future work with some new contacts before returning for his June wedding.

Tragically, the wedding never took place. Four days into the crossing, the Titanic hit an iceberg in the North Atlantic ocean, and sank on the 15 April 1912, taking more than 1,500 passengers and crew members with it – Hartley included.

‘Gentlemen, it has been a privilege playing with you tonight’

In a depiction made famous by the 1997 film Titanic (see above), the eight musicians on board the ship continued to play amid the havoc, as women, children and first-class passengers were loaded hurriedly onto lifeboats.

At maximum capacity, the lifeboats barely had space for half the people on the ship, and as the wooden boats began to depart with seats still vacant, it soon became clear that many of those still on board the rapidly sinking cruise liner would not be saved.

As was his command, bandleader Wallace H. Hartley gathered his seven fellow musicians to play music in an attempt to calm the pandemonium and still people’s fears. Survivors of the ship report that the band played upbeat music, including ragtime and popular comic songs of the late 19th and early 20th century.

One of the popular myths surrounding the Titanic and its historic fate is that the band played the hymn ‘Nearer, My God, to Thee’ in their final moments. Some accounts dispute this, claiming that the musicians were last heard playing Archibald Joyce’s waltz, ‘Dream of Autumn’, before abandoning their instruments.

If the musicians were indeed playing music to the very end, it does seem likely that Hartley would have chosen the hymn as their swan song.

Hartley’s father, Albion, was the choirmaster at the Methodist chapel in the family’s hometown, and had introduced ‘Nearer, My God, to Thee’ to the congregation.

Hartley had also told a former colleague on the Mauretania that, should he ever find himself aboard a sinking ship, the hymn would be one of two pieces he would play in his final moments – a chilling foreshadowing of events to come.

Only three of the musicians’ bodies were recovered from the wreckage, including Hartley’s. A detailed inventory documents the personal effects that were found with him, including a gold fountain pen and silver match box, both engraved with his initials, and a diamond solitaire ring.

Rediscovered in an attic

Despite some reports to the contrary, there is no evidence that his violin was found strapped to his chest in its case. We do know, however, that it must have been recovered, along with a satchel embossed with Hartley’s initials, as a telegram transcript from Maria Robinson to the Provincial Secretary of Nova Scotia reads, ‘I would be most grateful if you could convey my heartfelt thanks to all who have made possible the return of my late fiancé’s violin’.

When Robinson died in 1939, her sister gave the violin to the Bridlington Salvation Army, who passed it on to a violin teacher. The teacher passed it on further, and in 2004 it was rediscovered in an attic in the UK.

Sceptics initially refused to believe that this could be the real thing, assuming that the violin would have been so badly damaged by water that it simply could not have survived.

However, after nine years of evidence gathering and forensic analysis, including CT scans and a certification by the Gemological Association of Great Britain, it was confirmed that this was, in fact, the violin that Wallace Hartley had played aboard the RMS Titanic.

Forensic experts certified that the engraving on the metal tailpiece was “contemporary with those made in 1910”, and that the instrument’s “corrosion deposits were considered compatible with immersion in sea water”.

Sold for nearly a million

On 19 October 2013, the violin was sold at auction by Henry Aldridge & Son in Wiltshire for £900,000 (equivalent to over £1,000,000 in 2022), a record figure for Titanic memorabilia. The previous record was thought to have been £220,000 paid in 2011 for a plan of the ship that had been used to inform the inquiry into the ship’s sinking.

The violin is irreparably damaged and deemed unplayable, with two large cracks caused by water damage and only two remaining strings. Its current owners are unknown, but believed to be British.

As for Hartley, he was buried in his hometown of Colne in Lancashire, at a funeral service that was attended by over 20,000 people, and included the hymn that will forever be associated with him, ‘Nearer, My God, to Thee’.

The headstone of his final resting place includes an inscription of the hymn’s opening notes, above a violin carved out of stone.

Tuesday, August 9, 2022

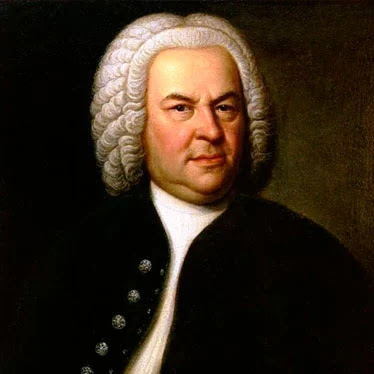

24 Amazing Facts About JS Bach

Published by Revelle Team on June 10, 2016

Baroque and Bach are two words that are very often linked together. Widely regarded as one of the definitive composers of the Baroque period, Johann Sebastian Bach’s works are still loved today as each new generation discovers his incredible gift.

However, many people are unaware that without some specific enthusiasm and recognition for this master’s classical works, Bach might have been relegated to obscurity. Only having been known as a skilled organist, musical mathematician, and that guy with the perfectly curled, white wig.

Fortunately however, his musical compositions were admired and appreciated by geniuses like of Mozart and Beethoven; and in 1829, nearly 60 years after his death, Felix Mendelssohn, carried Bach’s Passion According to St. Matthew out of oblivion and into the German concert hall for a significant historical event. Although it had been nearly a hundred years after this beautiful masterpiece had been composed, the concert ignited a flame of curiosity and re-evaluation of Bach’s work, resulting in a world-wide acknowledgement of his brilliance and importance to Baroque classical music.

Here are 24 additional facts and trivia about this famous composer:

Johann Sebastian Bach was born March 31, 1685 in Eisenach, Thuringia, Germany.

His father, Johann Ambrosius Bach was a 7th generation musician, and carried on the tradition by teaching him how to play the violin.

Bach lost both his parents when he was 10 years old. While living in Ohrdruf, Germany, his older brother Johann Christoph Bach taught him organ.

In 1700, he was granted a scholarship at St. Michael’s School in Luneburg for his fine voice.

During an inaugural recital on the new organ his talents earned him the job of organist in Arnstadt, in 1703, at New Church, where he provided music for the services at the church, as well as instruction in music to the local children.

Bach moved to Muhlhausen in 1707 to become the organist in the Church of St. Blaise.

Bach married his cousin, Maria Barbara Bach, and they had seven children. His sons Wilhelm Friedemann and Carl Philipp Emanuel became composers and musicians like their father.

Bach’s next position was as court organist in Weimer, in 1708 for Duke Wilhelm Ernst. It was here he composed his very famous Toccata in D Minor.

Bach was given a diamond ring in 1714 from the Crown Prince Fredrick of Sweden who was amazed at his playing.

Having angered Duke Wilhelm for requesting release from his position on short notice and desiring to go work for Prince Leopold of Koethen, Bach was arrested and put in jail for several weeks in 1716.

Upon his release from jail, Bach became the conductor of the court orchestra, in which Prince Leopold played.

In 1719, Bach tried to arrange a meeting with another prolific composer of that era, George Frideric Handel. Despite being only 130 kilometers apart, the two never did meet.

Bach’s wife, Maria, died suddenly in 1720 while he was away with Prince Leopold. She was 35 years old. The fifth and final movement of the Partita in D Minor for solo violin, “Chaconne,” was written to commemorate her.

In 1721, Bach married Anna Magdalena Wülcken. They had thirteen children.

Bach wrote the majority of his instrumental works during the Koethen period.

In 1723, he became the choir leader for two churches in Leipzig, Germany, in addition to teaching music classes and giving private lessons.

Most of Bach’s choral music was composed in Leipzig.

Bach’s deep religious faith could be found even in his secular music. He would put the initials “I.N.J.,” a Latin abbreviation that means, In Nomine Jesu, or “in the name of Jesus,”on his manuscripts.

The Brandenburg Concertos were written in 1721 as a tribute to the Duke of Brandenburg.

The Well-Tempered Clavier was composed as a collection of keyboard pieces to help students learn various keyboard techniques and methods.

Fredrick the Great, King of Prussia inspired Bach’s composition of a set of fugues called Musical Offering in 1740.

The Art of Fugue was begun in 1749 but was not completed.

After struggling with blindness and a failed surgery on his eyesight, Bach suffered a stroke and died in Leipzig, July 28, 1750. He was 65 years old.

His entire career was spent in a contracted area of Germany that is smaller than most of the States in America.

Johann Sebastian Bach is considered the quintessential composer of the Baroque era, and one of the most important figures in classical music in general. His complex musical style was nearly lost in history but gratefully it survives to be studied and enjoyed today. You can learn more about this icon by visiting his dedicated website. In the words of Johannes Brahms (1833-1897), “Study Bach: there you will find everything.”

30 Inspirational Quotes For Every Musician

Published by StringOvation Team on February 09, 2017

Most of us, from time to time feel discouraged. In fact, because we all need emotional boosts every once in a while, a large portion of social media content is motivational, designed to uplift your soul and the souls of others. So, in the spirit of time-honored encouragement, the following quotes are specifically for musicians. If you’ve been feeling down about your progress as a musician or just about where your talent might take you, the musings of these various composers and performers should help elevate your psyche.

The following inspirational quotes for musicians were gleaned from a variety of sources, including BrainyQuotes, Musicians Buy Line, Classic FM, and Quotes-Inspirational. They feature insights from musicians of all genres and levels of success, as well as a few from composers, philosophers, and other iconic thinkers.

Igor Stravinsky: "Lesser artists borrow, great artists steal."

J.S. Bach: "I was obliged to be industrious. Whoever is equally industrious will succeed equally well."

Robert Schumann: "To send light into the darkness of men's hearts - such is the duty of the artist."

Dmitri Shostakovich: "A creative artist works on his next composition because he was not satisfied with his previous one."

Elvis Presley: “The truth is like the sun. You can shut it out for a time, but it ain't goin' away.”

Mick Jagger: “Lose your dreams and you might lose your mind.”

BB King: “The beautiful thing about learning is that nobody can take it away from you.”

Bob Marley: “One good thing about music, when it hits you, you feel no pain."

Pablo Casals: “Music is the divine way to tell beautiful, poetic things to the heart."

Billy Joel: “I think music in itself is healing. It's an explosive expression of humanity. It's something we are all touched by. No matter what culture we're from, everyone loves music."

John Lennon: “Life is what happens when you’re making other plans.”

Marcus Miller: “It's a great thing about being a musician; you don't stop until the day you die, you can improve. So it's a wonderful thing to do."

Thelonious Monk: “All musicians are potential band leaders.”

Sting: “If you play music with passion and love and honesty, then it will nourish your soul, heal your wounds and make your life worth living. Music is its own reward.”

Ludwig van Beethoven: “Music is a higher revelation than all wisdom and philosophy. Music is the electrical soil in which the spirit lives, thinks and invents.”

Bono (U2): “Music can change the world because it can change people.”

Carlos Santana: “Just as Jesus created wine from water, we humans are capable of transmuting emotion into music.”

John Denver: “Music does bring people together. It allows us to experience the same emotions. People everywhere are the same in heart and spirit. No matter what language we speak, what color we are, the form of our politics or the expression of our love and our faith, music proves: We are the same.”

Plato: “Music is the movement of sound to reach the soul for the education of its virtue.”

Thomas Carlyle: “Music is well said to be the speech of angels.”

Roy Ayers: “The true beauty of music is that it connects people. It carries a message, and we, the musicians, are the messengers.”

William Congreve: “Music hath charms to soothe the savage beast, to soften rocks or bend a knotted oak.”

Oliver Wendell Holmes: “Take a music bath once or twice a week for a few seasons, and you will find that it is to the soul what the water bath is to the body.”

Chris S. Salazar: “Music is by far the most wonderful method we have to remind us each day of the power of personal accomplishment.”

Karlheinz Stockhausen: “Whenever I felt happy about having discovered something, the first encounter, not only with the public, with other musicians, with specialists, etc, was that they rejected it.”

John McLaughlin: “At the risk of sounding hopelessly romantic, love is the key element. I really love to play with different musicians who come from different cultural backgrounds.”

Billy Joel: “Musicians want to be the loud voice for so many quiet hearts.”

Neil Diamond: “Because my musical training has been limited, I've never been restricted by what technical musicians might call a song.”

Igor Stravinsky: “Too many pieces of music finish too long after the end.”

Plato: “Music gives a soul to the universe, wings to the mind, flight to the imagination, and life to everything.”

You may have already heard some of these inspirational quotes for musicians, but it never hurts to hear them again.

.jpg)