by Georg Predota

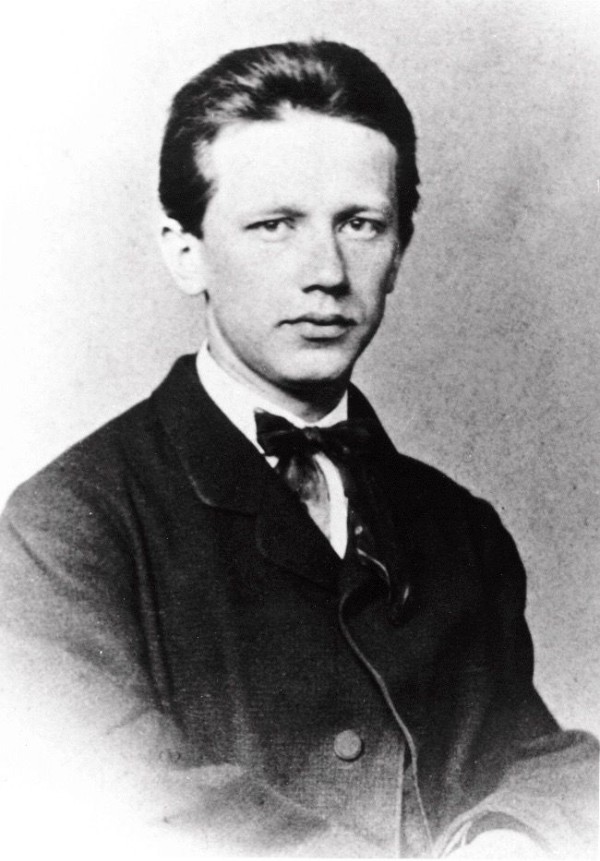

Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky at 23

Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky (1840–1893) stands as one of the most enigmatic and beloved figures in the Romantic era, a composer whose music pulses with raw emotion, sweeping melodies, and an unerring sense of drama. Born into the vast, turbulent landscape of imperial Russia, Tchaikovsky bridged the worlds of Western classical tradition and Slavic folk expression, creating works that resonate universally while deeply rooted in his personal struggles.

Recent scholarship has demythologised the composer’s image, moving beyond the mid-20th-century trope of a tortured homosexual soul to reveal a multifaceted artist. According to Simon Morrison, he was not “a tortured gay man but a fun-loving individual with a Monty Python sense of humour.”

His death on 6 November 1893 silenced a voice at its peak, yet his legacy endures in repertoires worldwide. “His art,” according to Morrison, “emerges as an abiding retort to the Romanticism of his time, directly expressive and self-controlled.” To commemorate his passing, let’s feature a composer who “changed the parameters of Russian music.”

From Ural Cradle to Conservatory Call

The young Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky in 1863

Tchaikovsky’s early life was marked by privilege and precocity, set against the backdrop of Russia’s cultural awakening. Born on 7 May 1840, in Votkinsk, a remote Ural mining town, to a middle-class family, he displayed musical talent from infancy.

A French governess introduced him to opera, and by age four, he improvised on the piano. Tragedy, however, struck early as his mother died from cholera in 1854. This left a scar that fuelled lifelong health anxieties.

Sent to St. Petersburg’s School of Jurisprudence, Tchaikovsky endured a regimented education, emerging in 1859 as a minor civil servant. Yet music called insistently. In 1862, at the age of 22, he enrolled in the newly founded St. Petersburg Conservatory under Anton Rubinstein, Russia’s pioneering musical educator.

The Hybrid Master

Scholarly accounts emphasise how this formal training shaped Tchaikovsky’s cosmopolitanism. Unlike the nationalist “Mighty Handful” consisting of Balakirev, Cui, Mussorgsky, Rimsky-Korsakov, and Borodin, who scorned conservatory “Westernism,” Tchaikovsky embraced it, blending Mozartian clarity with Russian soulfulness.

As Alexander Poznansky details in his publications on Tchaikovsky, the composer’s correspondence reveals a young man “eager to absorb European techniques while infusing them with Slavic passion.”

By 1866, he had joined Moscow’s Conservatory as a professor of harmony, a post that sustained him amid financial woes. This period birthed Tchaikovsky’s first masterpieces, where personal turmoil fuelled artistic fire. His Symphony No. 1 in G minor, “Winter Dreams” of 1868, evokes Russia’s frozen vastness with lyrical second themes that hint at the melancholy introspection defining his style.

Love Themes and Letter Scenes

Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky in 1893

But it was the Romeo and Juliet Fantasy Overture, scored in 1869 and revised in 1880 that catapulted him to fame. Inspired by Shakespeare’s tragedy and prompted by Balakirev, the work’s soaring love theme played by solo oboe and strings captures star-crossed passion in a mere 20 minutes.

Musicologist David Brown praises its “emotional directness,” noting how the friar’s chorale motif underscores fate’s inexorability. The musical highlight is the climatic love theme, swelling with harp arpeggios and horn calls. It is a sonic embrace that represents “a microcosm of Tchaikovsky’s heart-on-sleeve Romanticism.”

The 1870’s brought professional ascent and personal crisis. Tchaikovsky’s opera Eugene Onegin premiered modestly but endures as a staple. Its “Letter Scene,” where Tatiana pours out unrequited love in a soaring aria, exemplifies his gift for vocal lyricism. As scholars observe, “Tchaikovsky’s operas… throw considerable light on his creative personality, blending irony and pathos to mirror the composer’s own romantic disillusionments.”

Breakdown to Breakthrough

Tchaikovsky with his wife Antonina Milykova

A disastrous marriage to student Antonina Milykova in 1877, lasting six weeks, triggered a nervous breakdown. Fleeing to Italy and Switzerland, Tchaikovsky poured anguish into his Fourth Symphony in F minor. This symphony, dedicated to his secret patron Nadezhda von Meck, is a cornerstone of his oeuvre.

Von Meck, a wealthy widow, provided 6,000 rubles annually from 1877–1890, freeing him to compose without teaching. Their 1,200-letter correspondence, platonic and profound exchange deeply personal thoughts on music, life, and philosophy, though they never met in person.

The Fourth’s famed “fate motif” in the blaring horns in the opening recurs like a harbinger, symbolising life’s intrusion on happiness. Recent analysis locates a work “poised between East and West,” with Russian folk inflections in the scherzo’s pizzicato strings evoking sleigh bells.”

Ballet Revolution

Nadezhda von Meck

Ballets, often dismissed as “light” in Tchaikovsky’s canon, showcase his theatrical genius and rank among his most enduring highlights. Swan Lake of 1877, commissioned by Moscow’s Imperial Theatre, weaves a fairy-tale curse into orchestral splendour. Premiering to mixed reviews, its revised 1895 version triumphed. The “Swan Theme” has been interpreted as “a barometer of the aesthetic and political climates,” mirroring Tchaikovsky’s hidden self.

The Sleeping Beauty of 1890, scored for Paris’ Mariinsky Theatre, revels in opulent waltzes. Tchaikovsky took pride here, calling it “brilliant and organic.” The “Rose Adage” lilting horns and harp glissandi evoke courtly romance, a musical highlight of crystalline orchestration.

The Nutcracker of 1892 completes the triumvirate, although it flopped at the premiere.

A Christmas fantasia drawn from E.T.A. Hoffmann, it brims with invention. Gerald Abraham, “deems it characterful… with structural fluency.” Here, Tchaikovsky elevated dance music “into the ranks of the highest respected classical forms.”

Thunderous Keys and Dying Embers

Yosif Kotek and Tchaikovsky

Concertos reveal Tchaikovsky’s virtuosic flair. The Piano Concerto No. 1 in B-flat minor opens with iconic horn fanfares over piano thunder, a gesture initially rejected as “too showy.” Its martial first movement yields to a radiant second-theme melody, passed from piano to orchestra like a lovers’ duet. Its sweeping melodies and dramatic contrasts make it a staple for pianists.

The Violin Concerto, dedicated to pupil Yosif Kotek amid post-marriage exile, faced Auer’s initial scorn but premiered triumphantly in 1881. Its second movement’s “Canzonetta” is a tearful jewel, and the finale a Cossack romp. Auer later remarked, “its emotional depth stems from Tchaikovsky’s inner conflicts.”

Later symphonies plumb existential depths. The Fifth in E minor cycles a fate motto from brooding lament to victorious hymn. The Symphony No. 6, “Pathétique,” premiered days before his death, unfolds in tragic arcs. The first movement presents an anguished march, the third a despairing waltz, and the finale glows with dying embers. Tchaikovsky dedicated it to his nephew Bob Davydov, amid rumours of romantic attachment. Poznansky argues it reflects “no unbearable guilt” over sexuality, but a “natural part of his personality.”

Crucible of Soul

Tchaikovsky’s life and art, forged in the crucible of personal anguish and boundless imagination, transcended the rigid divide between Russian soul and Western craft. From the frost-kissed reveries of Winter Dreams to the heart-rending adagio of the Pathétique, his music remains an unflinching mirror to the human condition, expressive yet disciplined, intimate yet universal.

Where the “Mighty Handful” sought to banish Western influence in favour of raw folk idioms, Tchaikovsky absorbed Mozart’s architecture and Beethoven’s pathos, then refracted them through the prism of Slavic melancholy and Orthodox chant. The result was a language at once cosmopolitan and confessional.

Beneath the music lay a man who defied caricature. The old portrait of a suicidal homosexual, codified by Soviet censorship and Western pathos, has crumbled under scrutiny. Poznansky’s archival excavations reveal a correspondent who joked about bad reviews, teased von Meck about her hypochondria, and signed letters with playful diminutives. Apparently, Tchaikovsky once sent a mock-funeral march to a friend who overslept, complete with trombone glissandi.

Russian Soul and World Stage

This lightness coexisted with profound vulnerability, including health terrors, a six-week marriage that nearly unmade him, and the unspoken contract with von Meck that barred them from ever meeting.

Yet from these fractures emerged a creative discipline almost ascetic in its rigour. He revised Romeo and Juliet thrice, shaved excess from the Pathétique until its despair felt inevitable, and orchestrated The Sleeping Beauty with a jeweller’s precision.

Tchaikovsky did not merely change Russian music, but he globalised the Russian heart, proving that the most personal confession, when wedded to universal craft, becomes the common property of humankind.