By Frances Wilson, Interlude

© Garry Gay

J.S. Bach: Jesu Joy of Man’s Desiring (arr. Myra Hess)

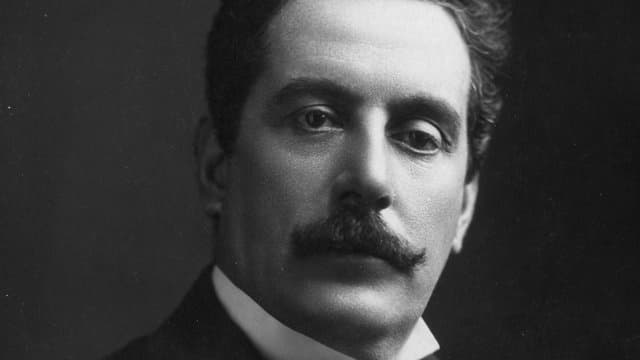

Myra Hess

Jesu, Joy of Man’s Desiring is the English title of the 10th movement from Bach’s cantata “Herz und Mund und Tat und Leben,” BWV 147. The British pianist Myra Hess published her transcription for solo piano in 1926 and later followed it with a version of piano 4-hands. Its simple elegance is underpinned by a resonant bass line which brings grandeur to one of Bach’s most enduring and popular works.

Percy Grainger: Sussex Mummer’s Carol

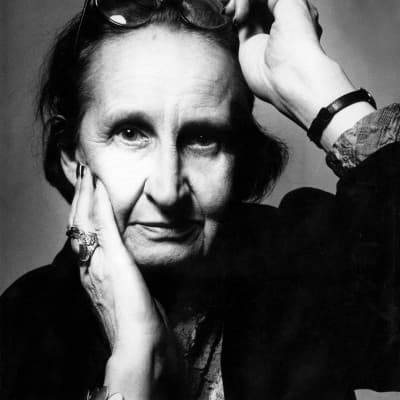

Percy Grainger

Percy Grainger had an avid interest in British folk songs and was a key figure in the folksong revival movement at the turn of the twentieth century. He made many wonderful transcriptions of folksongs from the British Isles, through which he introduced these pieces to concert audiences. The Sussex Mummers’ Carol is known to have been sung in the English county of Sussex as early as the 1800s and possibly even earlier (“mummers” were players who would go round villages re-enacting Biblical stories and folk tales for the local people). Grainger’s refined and peaceful transcription is a world away from the original setting in which a carol like this would be performed. Here, he demonstrates his skill in elevating a rustic tune into a concert miniature.

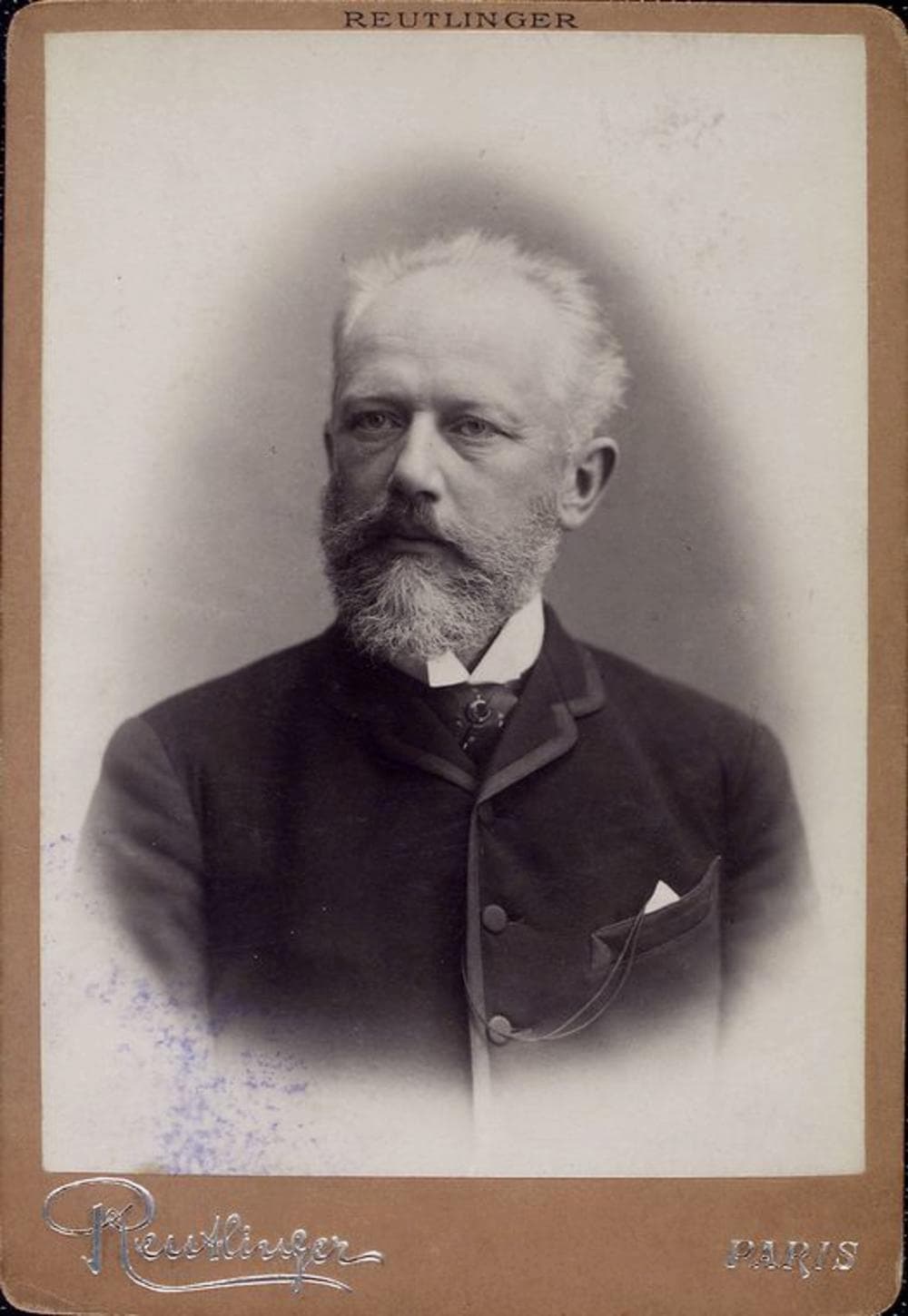

Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky: December – Noel from The Seasons

Tchaikovsky composed his twelve character pieces for piano, The Seasons, at the same time as he was writing his popular ballet, Swan Lake. December: Noel is scored in warm A-flat major and opens with a sweetly decorated melody. The piece evokes the good cheer and antics of Christmas.

Franz Liszt: Weihnachtsbaum (Christmas Tree)

Composed in 1873-76, Franz Liszt’s suite of 12 miniatures for piano was dedicated to the composer’s first grandchild, Daniela von Bülow (1860-1940; daughter of Cosima and Hans von Bülow). While some of the pieces directly reference well-known Christmas carols, including In Dulce Jubilo (No. 3) and Adeste Fideles (O Comes All Ye Faithful; No. 4), or evoke Christmas bells Chimes (No. 6), others are not connected with Christmas at all. The overall style and mood of the suite is reminiscent of Schumann’s Kinderszenen. The first recording of Weinachtsbaum was made in 1951 by Alfred Brendel.

Julian Yu: Jangled Bells

A witty, off-key take on that evergreen Christmas song by Chinese-Australian composer Julian Yu. After suggesting the well-known tune in the opening the music descends into a discordant middle section before the melody returns. The entire piece lasts just under 1 minute!

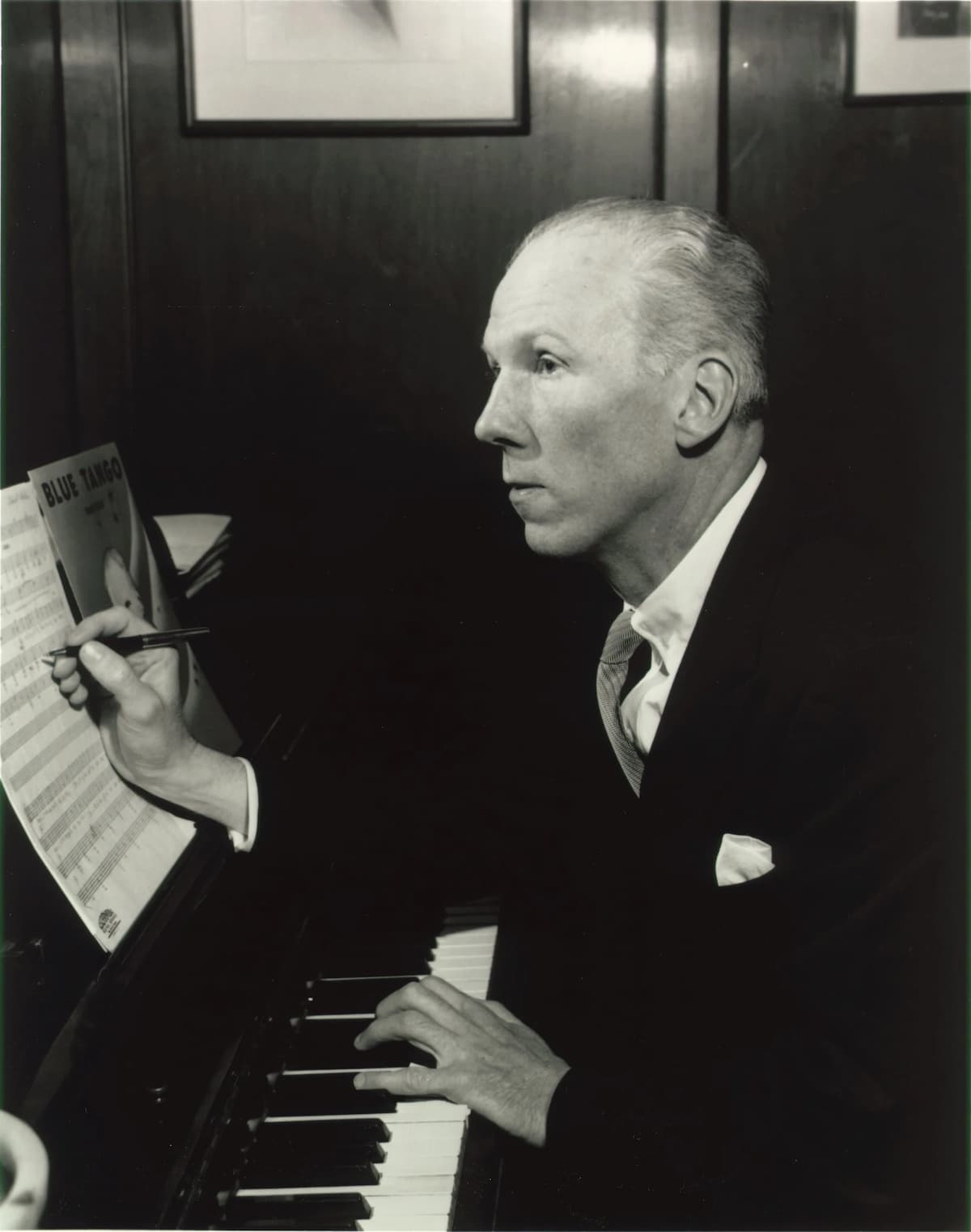

Leroy Anderson: Sleigh Ride (arr. Andrew Gentile)

Leroy Anderson

Composer Leroy Anderson had the original idea for Sleigh Ride during a heatwave! The work was completed in February 1948. Andrew Gentile’s dazzlingly imaginative transcription for solo piano is a masterpiece of virtuosity, complete with Lisztian flourishes and glittering glissandi, while honouring Anderson’s orchestral original. No Christmas playlist should be without this joyful, uplifting piece!