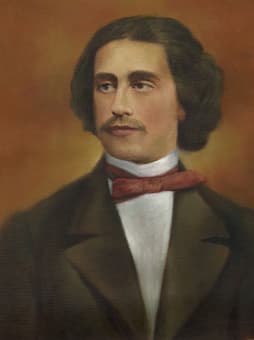

From lazy woodland creatures on a hot summer’s day to the plains of southern Spain, Claude Debussy is the unparalleled master of evocative musical imagery.

Forever entwined in the imaginations of his admirers with lethargic fauns, and idyllic woodlands thick with summer haze, Claude Debussy was classical music’s answer to the impressionist art movement which took Paris by storm in the mid to late 19th century.

As Monet, Cézanne and Renoir were masters of the visual arts, so Debussy was a master at crafting intricate and mesmerising soundscapes, transporting his audiences to dream-like worlds with his musical reveries.

Petite Suite (1907)

Originally written for piano with four hands, Debussy’s Petite Suite was orchestrated by his colleague Henri Büsser in 1907. Made up of four movements, the first evokes a picturesque seaside vista. Titled ‘En bateau’, or ‘Sailing’, it’s easy to imagine boats and dinghies bobbing over gently rocking waves, as a flute melody soars over sighing strings and glissandos.

Jeux (1913)

Debussy’s Jeux is a one-of-a-kind piece of music. Premiered in the Théâtre des Champs-Élysées in 1913, just two weeks before Stravinsky’s riot-inducing Rite of Spring, it was described by the composer as a ‘danced poem’. The piece was written at the request of dynamic ballet duo Sergei Diaghilev and legendary choreographer Vaslav Nijinsky, to be performed by Diaghilev’s company, Ballets Russes. It follows a vague storyline of a boy, two girls, and a tennis ball, which goes ultimately unresolved – much like many of Debussy’s harmonies.

Ibéria (1912)

The second movement of Images pour orchestre, ‘Ibéria’ consists of three movements itself, each depicting images of Spain: its streets and paths, the scents of night, and the ‘morning of a festive day’. It’s an adventurous musical wonderland of jingling percussion, clacking castanets and chiming church bells, evocative of the sunny Iberian peninsula.

La fille aux cheveux de lin (1910)

Debussy wrote two books of solo piano preludes, the first in 1909-1910 and the second in 1912-1913. By far the best known, is La fille aux cheveux de lin, or ‘The Girl with the Flaxen Hair’. With a performance marking meaning ‘very calm and sweetly expressive’, it’s a short and simple work that, over the course of just a few minutes, perfectly depicts the soft innocence that is often associated with golden hair in fine art.

Rêverie (1884)

Debussy’s Rêverie is another one of those beautifully dream-like solo piano pieces that cements its composer as one of the 20th-century greats. With gently oscillating motifs, contrasting rhythms in the left and right hands, and plenty of rubato, the music creates a blissful sense of floating and weightlessness.

Pelléas et Mélisande (1902)

Although he began to write several, Pelléas et Mélisande is the only that Debussy completed. As a young composer Debussy was in awe of Wagner’s operas, traveling to the Bayreuth Festival to see them. And yet, as he told a friend, he had to be careful not to allow the 19th-century opera titan’s works to influence him too much: he had seen fellow French composers attempt to imitate the style, and thought it “dreary”. And so Pelléas et Mélisande is the perfect melting pot of laissez-faire French impressionism and Wagnerian drama.

La mer (1905)

La mer, which translates to ‘The Sea’, was first performed in Paris in late 1905. Inspired by artists’ depictions of the sea rather than the sea itself, one of the criticisms following an icy reception at the premiere was, “I do not hear, I do not see, I do not smell the sea”. Other critics wrote that it did not depict the sea, but rather “some agitated water in a saucer”. Nevertheless, on consecutive performances the piece was much more favourably received, and remains a favourite among the world’s top orchestras to this day.

Clair de lune (1905)

Think of relaxing piano music, and Debussy’s gorgeous ‘Clair de lune’ probably comes to mind. It’s the third, and most famous, movement from Suite bergamasque, which Debussy began writing in 1890 and ultimately finished in 1905. So the story goes, Debussy didn’t originally want these early pieces made public, but eventually accepted a publisher’s offer – and thank goodness he did.

Deux Arabesques (1891)

Debussy wrote his Deux Arabesques for solo piano while still in his 20s, between 1888 and 1891. Despite the composer’s young age, the whimsical and dream-like character his music would come to be known and loved for can already be heard, carving the way for French Impressionism in music.

Prélude à l'après-midi d'un faune (1894)

Beginning with one of the most iconic orchestral solos ever written, Debussy wrote Prélude à l’après-midi d’un faune (‘Prelude to the Afternoon of a Faun’) in 1894. His inspiration was a poem by Stéphane Mallarmé, in which a faun awakes from his afternoon slumber and recounts a series of rendezvous with forest nymphs. Debussy’s meandering score and rich orchestration captivates his audience and brings them to the heart of the forest on a balmy summer’s day, to hear the tales of the faun’s afternoon amidst the heady pinewood scents, floating through the breeze.