by

Vltava in Prague

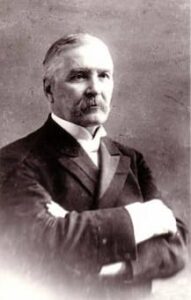

The conductor Adolf Čech (1841-1903) premiered a number of significant works by Antonín Dvořák, Zdeněk Fibich, and Bedřich Smetana. Such was the case on 4 April 1875, when he took the podium with the Orchestra of the Prague Provisional Theatre in a musical depiction of Bohemia’s longest river. Smetana tone poem Vltava (The Moldau), perhaps the most famous river journey ever sounded in music, was rapturously received by audiences and critics alike.

Adolf Čech

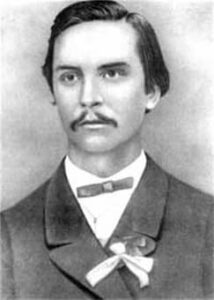

Smetana had actually composed the work after losing his hearing completely. He had noticed substantial hearing loss in 1874, and he informed the Provisional Theatre’s management of his situation. “It was in July… that I noticed that in one of my ears the notes in the higher octaves were pitched differently than in the other and that at times I had a tingling feeling in my ears and heard a noise as though I was standing by a mighty waterfall. My condition changed continuously up to the end of July when it became a permanent state of affairs and it was accompanied by spells of giddiness so that I staggered to and fro and could walk straight only with the greatest concentration.” And while he could no longer perform music, he certainly could still write. Almost immediately “he plunged into composing the first two movements of his Má Vlast (My Country) cycle.”

Bedřich Smetana

Like many educated Bohemians, Smetana spoke German rather than Czech, and his musical education and orientation were entirely Germanic. Yet, he was profoundly sympathetic to the patriotic yearnings of his fellow people. Political stirrings of national identity and pride ignited a great awakening across Europe in 1848. Urging an end to Habsburg absolutist rule, Smetana openly participated in this revolution, and he was barely able to escape arrest. Unable to establish a career in Prague, Smetana left for exile in Sweden. Once he was able to return, he devoted himself to a musical career in Prague that would honour his homeland. Stirred by the rhythms and melodies of Czech folk music, he created a new and unique poetic language. Smetana enthusiastically envisioned operas and symphonic works based on themes from Czech history and mythology, and he proudly proclaimed, “I am Czech in body and soul.” The establishment of the Provisional Theatre in 1863 celebrated the autonomy of a unique Czech nation, and it exclusively promoted Czech music, specifically Czech nationalist opera.

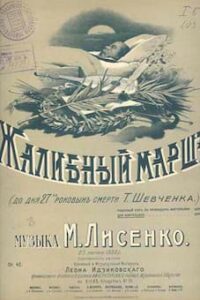

František Dvořák: Bedřich Smetana and Friends in 1865

Smetana’s comic opera The Bartered Bride is the intimate realisation of the composer’s artistic vision. Set in a country village with realistic characters, the spirited heroine has to use all her determination, charm and cunning to marry the man she loves. It is a joyous celebration of Czech culture and identity, and the distinct rhythmic inflections of the Czech language and of Czech folk dances combine irresistibly. Smetana said he was trying to give the music “a popular character, because the plot was taken from village life and demanded a national treatment.”

Provisional Theatre, Prague

In so doing, he rhythmically referenced the characteristic folk dances of Bohemia—the polka, the skočná and the furiant. Smetana provides only occasional glimpses of authentic Czech folk melodies, and the habitual emphasis on the authenticity of the setting and costumes in productions is primarily a matter of staging. Nevertheless, Smetana “clearly felt the pulse of peasantry” and the simplicity of the music not only connected to a broad folk base, but also proved highly inspirational to the emerging independence movement.

Vltava from Bohnice

The subject of turning the Vltava River into a tone poem first occurred to Smetana in August 1867. Traveling with his musical friend Mořic Anger to the western edge of Bohemia, near its border with Germany, Anger recalled. “Great and unforgettable was the impression made on Smetana by our outing to Čenek’s sawmill in Hirschenstein, where the Křemelná joins the River Vydra. It was there that the first ideas for his majestic symphonic poem Vltava were born and took shape. Here he heard the gentle, poetic song of the two streams. He stood there, deep in thought. He sat down and stayed there, motionless as though in a trance. Smetana looked around at the enchantingly lovely countryside, at the confluence of the streams, he followed the Otava, accompanying it in spirit to the spot where it joins the Vltava, and within him sounded the first chords of the two motives which intertwine and increase and later grow and swell into a mighty melodic stream.” Smetana’s river journey was well received across the political spectrum. For the feared critic Eduard Hanslick, “Smetana was at bottom a German composer; for the radical German nationalist critics, the composer’s Czech nationalism was seen as a salutary model for properly German national composers to emulate.

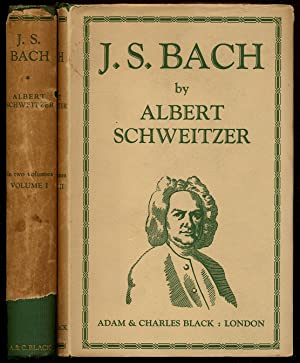

Schweitzer’s theological acumen also uniquely paved the way for his scholarly and practical interpretation of

Schweitzer’s theological acumen also uniquely paved the way for his scholarly and practical interpretation of

Arguably one of Rachmaninoff’s most famous pieces The Prelude Op. 3 No.2 is in C# minor and launched Rachmaninoff’s career after he performed this piece in 1892. Composers believe that particular keys evoke discernable and unique feelings. On the piano, this key uses many of the black keys with its slow chords, and one senses anxiety and tension from the beginning. There is a story that the inspiration for this work was a dream Rachmaninoff experienced: Set at a funeral where the coffin is prominently placed, he approaches the coffin, and to his horror he sees himself inside! That calls for a minor key!

Arguably one of Rachmaninoff’s most famous pieces The Prelude Op. 3 No.2 is in C# minor and launched Rachmaninoff’s career after he performed this piece in 1892. Composers believe that particular keys evoke discernable and unique feelings. On the piano, this key uses many of the black keys with its slow chords, and one senses anxiety and tension from the beginning. There is a story that the inspiration for this work was a dream Rachmaninoff experienced: Set at a funeral where the coffin is prominently placed, he approaches the coffin, and to his horror he sees himself inside! That calls for a minor key!

It really is too bad that Georg Philipp Telemann (1681-1767) did not have a large social network following! Throughout his long and industrious career, he wrote well over 3000 works. It’s no surprise that 18th-century critics unanimously considered him among the best composers of his time. Leading theorists held up his works as compositional models, and his fame extended to Holland, Switzerland, Belgium, France, Italy, England, Spain, Norway, Denmark and the Baltic lands. Yet by the early years of the 19th century, appreciation of Telemann’s music was in rapid decline. The main criticism turned out to be rather tongue in cheek. “In general,” a music historian wrote, “Telemann would have been greater had it not been so easy for him to write so unspeakably much. Polygraphs seldom produce masterpieces.” And once his music was compared according to the very different aesthetic standards of

It really is too bad that Georg Philipp Telemann (1681-1767) did not have a large social network following! Throughout his long and industrious career, he wrote well over 3000 works. It’s no surprise that 18th-century critics unanimously considered him among the best composers of his time. Leading theorists held up his works as compositional models, and his fame extended to Holland, Switzerland, Belgium, France, Italy, England, Spain, Norway, Denmark and the Baltic lands. Yet by the early years of the 19th century, appreciation of Telemann’s music was in rapid decline. The main criticism turned out to be rather tongue in cheek. “In general,” a music historian wrote, “Telemann would have been greater had it not been so easy for him to write so unspeakably much. Polygraphs seldom produce masterpieces.” And once his music was compared according to the very different aesthetic standards of  During his career as a composer of church music Telemann wrote at least 1700 cantatas! Always imaginative in his handling of vocal and instrumental color, Telemann’s transparent counterpoint was highly valued by his contemporaries. As you might well imagine, his cantata settings embrace a wide range of styles, forms and employment of instrumental forces. Significantly, a substantial number of Telemann’s sacred cantatas were not exclusively tied to performances in sacred venues, but could also be used for domestic devotions. In the foreword to the second collection of the Harmonischer Gottes-Dienst (Harmonic Service to the Lord) of 1731 he writes, “Two instruments of dissimilar kinds are so arranged that one person of his own can make us of the clavier without the addition of another instrument.”

During his career as a composer of church music Telemann wrote at least 1700 cantatas! Always imaginative in his handling of vocal and instrumental color, Telemann’s transparent counterpoint was highly valued by his contemporaries. As you might well imagine, his cantata settings embrace a wide range of styles, forms and employment of instrumental forces. Significantly, a substantial number of Telemann’s sacred cantatas were not exclusively tied to performances in sacred venues, but could also be used for domestic devotions. In the foreword to the second collection of the Harmonischer Gottes-Dienst (Harmonic Service to the Lord) of 1731 he writes, “Two instruments of dissimilar kinds are so arranged that one person of his own can make us of the clavier without the addition of another instrument.” Telemann is known to have composed approximately 125 orchestral suites, 125 concertos, several dozen other orchestral works and sonatas in five to seven parts, nearly 40 quartets, 130 trios, 87 solos, 80 works for one to four instruments without bass and roughly 250 pieces for keyboard. Now that’s what I call a life’s work! For the most part Telemann wrote his instrumental works for small performing forces, making them appropriate for domestic use. Historically significant, Telemann popularized the French-style orchestral suite in Germany paving the way for the works of J. S. Bach and others. Telemann was a kind and gentle man capable of witty humor, so entire works or individual movements have amusing programmatic titles. The Suite Burlesque de Quixotte includes the famous attack on the windmills, and the Suite La Bourse offers a musical account of the Parisian stock market crash of 1720!

Telemann is known to have composed approximately 125 orchestral suites, 125 concertos, several dozen other orchestral works and sonatas in five to seven parts, nearly 40 quartets, 130 trios, 87 solos, 80 works for one to four instruments without bass and roughly 250 pieces for keyboard. Now that’s what I call a life’s work! For the most part Telemann wrote his instrumental works for small performing forces, making them appropriate for domestic use. Historically significant, Telemann popularized the French-style orchestral suite in Germany paving the way for the works of J. S. Bach and others. Telemann was a kind and gentle man capable of witty humor, so entire works or individual movements have amusing programmatic titles. The Suite Burlesque de Quixotte includes the famous attack on the windmills, and the Suite La Bourse offers a musical account of the Parisian stock market crash of 1720!