Screen actors playing musicians: the best and worst examples

Actors ‘playing’ instruments on screen can be the stuff of nightmares. But, asks Michael Beek, to what lengths have they gone to make it look convincing?

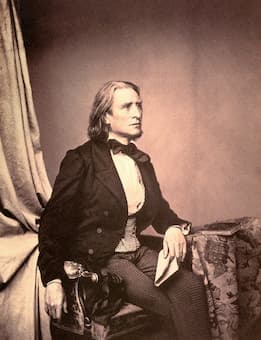

James Stewart learned the trombone for his role in The Glenn Miller Story © Getty

Michael Beek

In Humoresque (1946), John Garfield plays a virtuoso violinist. By then, Garfield was an Oscar-nominated actor, but he was no violinist. That said, his ‘performances’ are pretty convincing. Why? Because at least one of his arms is actually that of the great Isaac Stern. Similarly, in Deception (1946), a film released a few months prior, Paul Henreid plays a leading cellist. His performances were achieved thanks to the arms of a pair of professional cellists, accommodated by Henreid’s oversized jacket. Cosy...

Actors playing musicians: can you spot a fake?

Smoke and mirrors can only do so much, though, and not all filmmakers go to such creative lengths. So, is it fair to say you can spot a fake musician a mile off? Julian Lloyd Webber certainly thinks so. ‘When you see them, they’re pretty much always terrible,’ says the British cellist; ‘it’s rare that you see them and think they’ve actually got it right. I mean Deception does, because they’ve got people who are professionals doing that job. I think it’s not possible for someone who doesn’t play at all to make a convincing job of it – I don’t see how they can. Shine was pretty good… the fact he played the piano himself just says it all.’

He is of course referring to Scott Hicks’s 1996 film, in which Geoffrey Rush gave an Oscar-winning performance as Australian pianist David Helfgott. Rush played as a youngster and happily returned to the keyboard to put in the hours to take on the role; indeed, he performs on screen himself, even in close-up. The actors playing the younger Helfgott in flashbacks, Alex Rafalowicz and Noah Taylor, were hand-doubled in close-up by pianists Simon Tedeschi and Martin Cousin. It’s a well-tested means of capturing a more realistic performance.

Tricks of the camera: the hand double

Unlike Geoffrey Rush, and despite months of tuition and practice, actor Adrian Brody used a hand double for his role as Wladysław Szpilman in Roman Polanski’s The Pianist (2002). Janusz Olejniczak did the honours for the performance, which otherwise won Brody an Oscar.

Someone with experience of hand doubling is French pianist Alexandre Tharaud, whose fingers recently appeared in Anne Fontaine’s Boléro, about Maurice Ravel – he also plays music critic Pierre Lalo in the film. Actor Raphaël Personnaz portrays Ravel and while he undertook piano lessons for the role, it is Tharaud doing a lot of the work, as he explains. ‘When you see the hands with his face it’s him, but when you see only the hands it’s my hands. Sometimes you see his hands, then my hands, then his hands, and we have totally different hands! But nobody thought that was a problem...’

Tharaud shared a costume with Personnaz in order to match the sleeves on camera, pre-recorded the tracks for them both to play to on set, shot scenes at Ravel’s Parisian house and even played Ravel’s piano. He admits it was a surreal experience. ‘I wore the same suit and robe as Raphaël, so it was a little bit sweaty. I played to the playback of what I recorded three weeks before, on the same model of piano – when I recorded it, I tried to play with mistakes, because Ravel wasn’t a good pianist. So, I was dressed as Ravel, at his piano playing to my own recording, which was trying to imitate him! It was a very deep connection and it’s difficult to explain what I felt.’

Non-essential music making on screen

In these cases, the need for an actor to take to the keyboard or pick up a bow is unavoidable, music being at the heart of the story. But sometimes film or TV characters just happen to be written as musicians. Tim Burton’s Netflix series Wednesday sees the titular Wednesday Addams, iconic from decades-old comic strips, movies and TV series, recast as a cellist. For the producers it was a means of allowing the character (a closed book, emotionally) to open up, the cello an outlet for her feelings.

That’s all well and good, but for Jenna Ortega (who plays her) it meant not only breathing life into Addams but getting to grips with the cello. I show Julian Lloyd Webber a clip and ask what he thinks of her technique. ‘I was impressed by the fact that she’d bothered to actually learn the cello a little bit,’ he replies. ‘Although it’s obvious she’s not playing that complicated piece, at least you know she’s had a go.’

Actors learning instruments for a role... how good can they get?

Plenty of actors have ‘had a go’ with varying levels of success. James Stewart learned the trombone for The Glenn Miller Story (1954) and apparently had every intention of being heard in the film. Alas, the sound he made was so bad he mimed to recordings of his coach, Joe Yukl. Ryan Gosling learned at the keyboard for months before playing a fictional jazz pianist in La La Land (2016), while Emily Watson carried a cello around with her for a lengthy period ahead of portraying Jacqueline du Pré in Anand Tucker’s Hilary and Jackie (1998). Watson was coached by cellist Caroline Dale, who performed most of what we hear in the film, and Watson received an Oscar nomination for her portrayal.

It’s not a film Lloyd Webber is keen to champion, however, having known the real du Pré. ‘I think Emily Watson was very good, but it was a sort of hatchet job, really, and I’m very against the film. There were so many bad things in it; the worst, and the one that you know just would never happen, was when you see her leave her Stradivari out overnight in the snow in Russia. That is just stupid.’

Is it more difficult to pretend to play a violin than a piano?

Weather-related offences aside, I ask Lloyd Webber if it is perhaps more difficult to pretend to play a stringed instrument over, say, the piano, which an actor can hide behind to a certain degree. ‘I think it probably is more difficult,’ he says, ‘because if you need to do a full front shot – which would have been the case in something like Hilary and Jackie – you know it’s got to be right. And it seldom is!’

Alexandre Tharaud rightly points out that there is more to playing the piano than we might think, though. ‘On a piano it’s not just the fingers; it’s a chain of muscles. We play with the whole body, the legs, the feet; the position is your relationship with the stage. So, if an actor tries to play piano, they will play with the fingers, and they are too focused on the keyboard.’

It’s a huge amount for an actor to take on, then, whatever the instrument, and while the likes of Julian Lloyd Webber might prefer that actors simply leave it to the professionals, some actors have gone the extra mile in order to pass muster.

Actors playing musicians... success stories

In A Late Quartet (2012), the late Philip Seymour Hoffman played the second violinist of a fictional New York string quartet (the Fugue Quartet). He threw himself into learning the instrument months before shooting began and was coached by violinist Nanae Iwata. The pair had weekly lessons, and Hoffman immersed himself in the violin. And it wasn’t just hold and technique; he wanted to understand every facet of how to live and work with the instrument and his quartet mates, as Iwata shares.

‘He asked how he would shift in his seat, or how he would talk to the others; eyelines etc. I don’t even think about those things, so I was then paying attention to them in order to help him. Even things like how you would hold the case, how you would open it and chit-chat while getting the instrument ready. He really wanted to feel comfortable doing that, so he practised at home. He told me, “I practised for 20 minutes straight, just opening the case and putting it back while I was talking to someone, and it was really difficult!” He wanted to look legit, and he really worked hard on it.’

Iwata was on set, too, when Hoffman had to ‘play’ – his movement, body language, fingering and bowing were all carefully choreographed to the music: Beethoven’s Op. 131 String Quartet. This was after hours of time together, Hoffman sometimes videoing Iwata or practising fingering and vibrato to make it look like he was a seasoned player. She was impressed by his commitment. ‘He wanted to feel like it was really coming from within him,’ she remembers, ‘and I really respected that.’

Fooling the viewer... Camera tricks and CGI

Like Hoffman, fellow actors Mark Ivanir (violin) and Catherine Keener (viola) did all their own ‘playing’ on camera, with Christopher Walken (cello) the only one to use a hand double for close ups. Much like Paul Henreid in 1946’s Deception, Walken’s left hand was that of cellist David Bakamjian, who snuggled into the actor’s back wearing matching shirtsleeves to blend in.

Today, digital effects are another way that filmmakers can attempt to maintain the crucial musicality of a real player. For her 2019 film Blanche comme neige, director Anne Fontaine simply replaced a real viola da gamba player’s head with an actor’s. It’s an expensive option, but one Alexandre Tharaud tells me they discussed using in Fontaine’s Boléro. ‘We were told we had to choose; if we did that, the money would have to be taken from somewhere else in the budget. I would have been Ravel, but only up to my neck!’

Pasting an actor’s head onto a musician’s body might solve part of the puzzle when depicting realistic music-making on screen, but would we buy it even then? When we’re expected to believe that the person we’re watching is not just playing the music, but hearing it and feeling it as well, something will surely always be lost in translation.