It's all about the classical music composers and their works from the last 400 years and much more about music. Hier erfahren Sie alles über die klassischen Komponisten und ihre Meisterwerke der letzten vierhundert Jahre und vieles mehr über Klassische Musik.

Total Pageviews

Monday, July 28, 2025

Mozart - Piano Concerto No.21, K.467 / Yeol Eum Son

Sunday, July 27, 2025

50 Classical Music Pieces Everyone Knows - with Titles!

Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky / Peter I. Tschaikowsky - his music and his life

Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky (born April 25 [May 7, New Style], 1840, Votkinsk, Russia—died October 25 [November 6], 1893, St. Petersburg) was the most popular Russian composer of all time. His music has always had great appeal for the general public in virtue of its tuneful, open-heart melodies, impressive harmonies, and colourful, picturesque orchestration, all of which evoke a profound emotional response. His oeuvre includes 7 symphonies, 11 operas, 3 ballets, 5 suites, 3 piano concertos, a violin concerto, 11 overtures (strictly speaking, 3 overtures and 8 single movement programmatic orchestral works), 4 cantatas, 20 choral works, 3 string quartets, a string sextet, and more than 100 songs and piano pieces.

Tchaikovsky was the second of six surviving children of Ilya Tchaikovsky, a manager of the Kamsko-Votkinsk metal works, and Alexandra Assier, a descendant of French émigrés. He manifested a clear interest in music from childhood, and his earliest musical impressions came from an orchestrina in the family home. At age four he made his first recorded attempt at composition, a song written with his younger sister Alexandra. In 1845 he began taking piano lessons with a local tutor, through which he became familiar with Frédéric Chopin’s mazurkas and the piano pieces of Friedrich Kalkbrenner. Since music education was not available in Russian institutions at that time, Tchaikovsky’s parents had not considered that their son might pursue a musical career. Instead, they chose to prepare the high-strung and sensitive boy for a career in the civil service.

In 1850 Tchaikovsky entered the prestigious Imperial School of Jurisprudence in St. Petersburg, a boarding institution for young boys, where he spent nine years. He proved a diligent and successful student who was popular among his peers. At the same time Tchaikovsky formed in this all-male environment intense emotional ties with several of his schoolmates.

In 1854 his mother fell victim to cholera and died. During the boy’s last years at the school, Tchaikovsky’s father finally came to realize his son’s vocation and invited the professional teacher Rudolph Kündinger to give him piano lessons. At age 17 Tchaikovsky came under the influence of the Italian singing instructor Luigi Piccioli, the first person to appreciate his musical talents, and thereafter Tchaikovsky developed a lifelong passion for Italian music. Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart’s Don Giovanni proved another revelation that deeply affected his musical taste. In the summer of 1861 he traveled outside Russia for the first time, visiting Germany, France, and England, and in October of that year he began attending music classes offered by the recently founded Russian Musical Society. When St. Petersburg Conservatory opened the following fall, Tchaikovsky was among its first students. After making the decision to dedicate his life to music, he resigned from the Ministry of Justice, where he had been employed as a clerk.

Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky autograph score

Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky autograph scoreAutograph score of Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky's song “My Genius, My Angel, My Friend” (1858), the earliest known of his autograph scores.

Tchaikovsky spent nearly three years at St. Petersburg Conservatory, studying harmony and counterpoint with Nikolay Zaremba and composition and instrumentation with Anton Rubinstein. Among his earliest orchestral works was an overture entitled The Storm (composed 1864), a mature attempt at dramatic program music. The first public performance of any of his works took place in August 1865, when Johann Strauss the Younger conducted Tchaikovsky’s Characteristic Dances at a concert in Pavlovsk, near St. Petersburg.

After graduating in December 1865, Tchaikovsky moved to Moscow to teach music theory at the Russian Musical Society, soon thereafter renamed the Moscow Conservatory. He found teaching difficult, but his friendship with the director, Nikolay Rubinstein, who had offered him the position in the first place, helped make it bearable. Within five years Tchaikovsky had produced his first symphony, Symphony No. 1 in G Minor (composed 1866; Winter Daydreams), and his first opera, The Voyevoda (1868).

In 1868 Tchaikovsky met a Belgian mezzo-soprano named Désirée Artôt, with whom he fleetingly contemplated a marriage, but their engagement ended in failure. The opera The Voyevoda was well received, even by the The Five, an influential group of nationalistic Russian composers who never appreciated the cosmopolitanism of Tchaikovsky’s music. In 1869 Tchaikovsky completed Romeo and Juliet, an overture in which he subtly adapted sonata form to mirror the dramatic structure of Shakespeare’s play. Nikolay Rubinstein conducted a successful performance of this work the following year, and it became the first of Tchaikovsky’s compositions eventually to enter the standard international classical repertoire.

In March 1871 the audience at Moscow’s Hall of Nobility witnessed the successful performance of Tchaikovsky’s String Quartet No. 1, and in April 1872 he finished another opera, The Oprichnik. While spending the summer at his sister’s estate in Ukraine, he began to work on his Symphony No. 2 in C Minor, later dubbed The Little Russian, which he completed later that year. The Oprichnik was first performed at the Maryinsky Theatre in St. Petersburg in April 1874. Despite its initial success, the opera did not convince the critics, with whom Tchaikovsky ultimately agreed. His next opera, Vakula the Smith (1874), later revised as Cherevichki (1885; The Little Shoes), was similarly judged. In his early operas the young composer experienced difficulty in striking a balance between creative fervour and his ability to assess critically the work in progress. However, his instrumental works began to earn him his reputation, and, at the end of 1874, Tchaikovsky wrote his Piano Concerto No. 1 in B-flat Minor, a work destined for fame despite its initial rejection by Rubinstein. The concerto premiered successfully in Boston in October 1875, with Hans von Bülow as the soloist. During the summer of 1875, Tchaikovsky composed Symphony No. 3 in D Major, which gained almost immediate acclaim in Russia.

At the very end of 1875, Tchaikovsky left Russia to travel in Europe. He was powerfully impressed by a performance of Georges Bizet’s Carmen at the Opéra-Comique in Paris; in contrast, the production of Richard Wagner’s Ring cycle, which he attended in Bayreuth, Germany, during the summer of 1876, left him cold. In November 1876 he put the final touches on his symphonic fantasia Francesca da Rimini, a work with which he felt particularly pleased. Earlier that year, Tchaikovsky had completed the composition of Swan Lake, which was the first in his famed trilogy of ballets. The ballet’s premiere took place on February 20, 1877, but it was not a success owing to poor staging and choreography, and it was soon dropped from the repertoire.

The growing popularity of Tchaikovsky’s music both within and outside of Russia inevitably resulted in public interest in him and his personal life. Although homosexuality was officially illegal in Russia, the authorities tolerated it among the upper classes. But social and familial pressures, as well as his discomfort with the fact that his younger brother Modest was exhibiting the same sexual tendencies, led to Tchaikovsky’s hasty decision in the summer of 1877 to marry Antonina Milyukova, a young and naive music student who had declared her love for him. Tchaikovsky’s homosexuality, combined with an almost complete lack of compatibility between the couple, resulted in matrimonial disaster—within weeks he fled abroad, never again to live with his wife. This experience forced Tchaikovsky to recognize that he could not find respectability through social conventions and that his sexual orientation could not be changed. On February 13, 1878, he wrote his brother Anatoly from Florence: “Only now, especially after the tale of my marriage, have I finally begun to understand that there is nothing more fruitless than not wanting to be that which I am by nature.”

The year 1876 saw the beginning of the extraordinary relationship that developed between Tchaikovsky and Nadezhda von Meck, the widow of a wealthy railroad tycoon; it became an important component of their lives for the next 14 years. A great admirer of his work, she chose to become his patroness and eventually arranged for him a regular monthly allowance; this enabled him in 1878 to resign from the conservatory and devote his efforts to writing music. Thereafter he could afford to spend the winters in Europe and return to Russia each summer. Although he and his benefactor agreed never to meet, they engaged in a voluminous correspondence that constitutes a remarkable historical and literary record. In the course of it they frankly exchanged their views on a broad spectrum of issues, starting with politics or ideology and ending with such topics as the psychology of creativity, religious faith, and the nature of love.

At the beginning of 1885, tired of his peregrinations, Tchaikovsky settled down in a rented country house near Klin, outside of Moscow. There he adopted a regular daily routine that included reading, walking in the forest, composing in the mornings and the afternoons, and playing piano duets with friends in the evenings. At the January 1887 premiere of his opera Cherevichki, he finally overcame his longstanding fear of conducting. Moreover, at the end of December he embarked upon his first European concert tour as a conductor, which included Leipzig, Berlin, Prague, Hamburg, Paris, and London. He met with great success and made a second tour in 1889. Between October 1888 and August 1889 he composed his second ballet, The Sleeping Beauty. During the winter of 1890, while staying in Florence, he concentrated on his third Pushkin opera, The Queen of Spades, which was written in just 44 days and is considered one of his finest. Later that year Tchaikovsky was informed by Nadezhda von Meck that she was close to ruin and could not continue his allowance. This was followed by the cessation of their correspondence, a circumstance that caused Tchaikovsky considerable anguish.

In the spring of 1891 Tchaikovsky was invited to visit the United States on the occasion of the inauguration of Carnegie Hall in New York City. He conducted before enthusiastic audiences in New York, Baltimore, and Philadelphia. Upon his return to Russia, he completed his last two compositions for the stage—the one-act opera Iolanta (1891) and a two-act ballet Nutcracker (1892). In February 1893 he began working on his Symphony No. 6 in B Minor (Pathétique), which was destined to become his most celebrated masterpiece. He dedicated it to his nephew Vladimir (Bob) Davydov, who in Tchaikovsky’s late years became increasingly an object of his passionate love. His world stature was confirmed by his triumphant European and American tours and his acceptance in June 1893 of an honorary doctorate from the University of Cambridge.

On October 16 Tchaikovsky conducted his new symphony’s premiere in St. Petersburg. The mixed reaction of the audience, however, did not affect the composer’s belief that the symphony belonged among his best work. On October 21 he suddenly became ill and was diagnosed with cholera, an epidemic that was sweeping through St. Petersburg. Despite all medical efforts to save him, he died four days later from complications arising from the disease. Wild rumours circulated among his contemporaries concerning his possible suicide, which were revived in the late 20th century by some of his biographers, but these allegations cannot be supported by documentary evidence.

Legacy

For most of the 20th century, critics were profoundly unjust in their severe pronouncements regarding Tchaikovsky’s life and music. During his lifetime, Russian musicians attacked his style as insufficiently nationalistic. In the Soviet Union, however, he became an official icon, of whom no adverse criticism was tolerated; by the same token, no in-depth studies were made of his personality. But in Europe and North America, Tchaikovsky often was judged on the basis of his sexuality, and his music was interpreted as the manifestation of his deviance. His life was portrayed as an incessant emotional turmoil, his character as morbid, hysterical, or guilt-ridden, and his works were proclaimed vulgar, sentimental, and even pathological. This interpretation was the result of a fallacy that over the course of decades projected the current perception of homosexuality onto the past. At the turn of the 21st century, a close scrutiny of Tchaikovsky’s correspondence and diaries, which finally became available to scholars in their uncensored form, led to the realization that this traditional portrayal was fundamentally wrong. As the archival material makes clear, Tchaikovsky eventually succeeded in his adjustment to the social realities of his time, and there is no reason to believe that he was particularly neurotic or that his music possesses any coded messages, as some theorists have claimed.

His artistic philosophy gave priority to what may be called “emotional progression”—i.e., the establishment of an immediate rapport with the audience through the anticipation and eventual achievement of catharsis. His music does not claim intellectual depth but conveys the joys, loves, and sorrows of the human heart with striking and poignant sincerity. In his attempt to synthesize the sublime with the introspective, and also in the symbolism of his later music, Tchaikovsky anticipated certain sensibilities that later became prominent in the culture of Russian modernism.

Tchaikovsky was the leading exponent of Romanticism in its characteristically Russian mold, which owes as much to the French and Italian musical traditions as it does to the German. Although not as ostentatiously as the nationalist composers, such as Modest Mussorgsky and Nikolay Rimsky-Korsakov, Tchaikovsky was clearly inspired by Russian folk music. In the words of the Russian-born composer Igor Stravinsky, “Tchaikovsky drew unconsciously from the true, popular sources of our race.”

The first great Russian symphonist, he exhibited a particular gift for melody and orchestration. In his best work, the powerful tunes underlining musical themes are harmonized into magnificent, formally innovative compositions. His resourceful use of instruments allows easy identification of most of his works by their characteristic sonority. Tchaikovsky excelled primarily as a master of instrumental music; his operas, often eclectic in subject matter and style, do not find much appreciation in the West, with the exception of Eugene Onegin and The Queen of Spades. Whereas most of his operas met with limited success, Tchaikovsky nonetheless proved eminently successful in transforming ballet, then a grand decorative gesture, into a staged musical drama, and thus he revolutionized the genre.

Moreover, Tchaikovsky brought an integrity of design that elevated ballet to the level of symphonic music. To this end, he employed a symphonist’s sense of large-scale structure, organizing successive dances through the use of keys to create a cumulative feeling of purpose, in distinction to the more random or decorative layout in the ballets of his predecessors. His special sense of how melody can engender the dance gave his ballets a unique place in the world’s theatres. The influence of his experimentation is evident in the ballets of Sergey Prokofiev and Aram Khachaturian.

Tchaikovsky’s symphonic poems are part of the line of development in single-movement programmatic works initiated by Franz Liszt, and they run the gamut of expressive and stylistic features that typify the genre. At one extreme the early Fatum (1868) shows a freedom of form and modernist expression. At the other extreme is the classical poise of the Romeo and Juliet fantasy overture, in which passionate Romanticism is counterbalanced by the rigours of the sonata form. Furthermore, Tchaikovsky loosened the strictures of chamber music by introducing unorthodox meter in the scherzo of the Second String Quartet in F Major, Opus 22 (1874), and undermining the sense of key in the finale. His innovation is also evident in the second movement of the string sextet Souvenir de Florence (1890), for which he wrote music that revels in almost pure sound-effect—something more familiar in the orchestral sphere. His skill in counterpoint, the traditional bedrock of chamber music, can also be seen throughout his chamber works.

Tchaikovsky’s approach to solo piano music, on the other hand, remained mostly traditional, that is, it more or less satisfied the 19th-century taste for short salon pieces with descriptive titles, usually arranged in groups, as in the famous The Seasons (1875–76). In several of his piano pieces, Tchaikovsky’s melodic flair surfaces, but on the whole he was far less committed when composing these works than he was when writing his orchestral music, concertos, operas, and chamber compositions.

Tchaikovsky steered an unlikely path between the Russian nationalist tendencies so prominent in the work of his rivals in The Five and the cosmopolitan stance encouraged by his conservatory training. He was both a Russian nationalist and a Westernizer of polished technical skill. He put his personal stamp on the late-19th-century symphony with his last three symphonies; they demonstrate a heightened subjectivity that would influence Gustav Mahler, Sergey Rachmaninoff, and Dmitry Shostakovich and encourage the genre to pass with renewed vigour into the 20th century.

It cannot be denied that the quality of Tchaikovsky’s oeuvre remains uneven. Some of his music is undistinguished—hastily written, repetitious, or self-indulgent. But in such symphonies as his No. 4, No. 5, No. 6, and Manfred and in many of his overtures, suites, and songs, he achieved the unity of melodic inspiration, dramatic content, and mastery of form that elevates him to the premiere rank of the world’s composers.

Tchaikovsky: Piano Concerto No. 1, Op. 23 - Anna Fedorova - Live Concert HD

Tchaikovsky: Fantasy Overture 'Romeo and Juliet' -

Saturday, July 26, 2025

Johann Strauss (son) - Die Fledermaus - Overture | Manfred Honeck | WDR ...

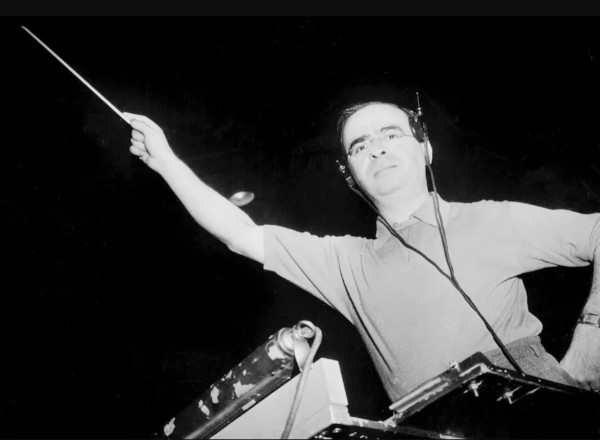

Max Steiner, the Movie Composer Injected With Amphetamines

By Emily E. Hogstad

Max Steiner, hailed as the “father of film music,” is one of the most influential composers in the history of Hollywood.

Over the course of a career that spanned half a century, Steiner crafted some of the most iconic scores in cinematic history.

Steiner was no stranger to the world of classical music. In fact, he took massive inspiration from Richard Wagner, his tutor Gustav Mahler, and even his godfather, Richard Strauss.

Today, we’re looking at the life of Max Steiner and his impact on the world of cinema…including the taxing work assignment with a deadline so tight, it required twenty-hour workdays and amphetamines to meet.

Max Steiner

Max Steiner’s Family Background

Max Steiner was born on 10 May 1888 in Vienna.

His family’s roots in Viennese arts and culture ran deep. He was named after his grandfather Maximilian Steiner, the theater director who popularised Viennese operetta and convinced Johann Strauss II to write for the genre.

Later, Maximilian’s son Gábor followed in his father’s footsteps and became an impresario himself.

Gábor’s wife Marie was also a music-lover and was a dancer early in her career, before giving birth to her only child, Max.

Max’s godfather was none other than composer Richard Strauss!

A Musically Precocious Childhood

Max’s voracious love of music was obvious from an early age. By the age of six, he was taking multiple music lessons a week.

He also started improvising on the piano, and with his father’s encouragement, writing the improvisations down.

At twelve, again with the support of his father, he conducted a performance of composer Gustave Kerker’s operetta The Belle of New York.

Max Steiner’s Musical Education

In 1904, he began attending the Imperial Academy of Music. While there, he was tutored by Gustav Mahler.

He breezed through four years of curriculum in one, studying composition, harmony, counterpoint, and a veritable orchestra’s worth of instruments.

Around this time, he also composed his first operetta, The Beautiful Greek Girl. No doubt to his disappointment, his father passed on staging it, claiming it wasn’t up to his standards.

Max rebelled by offering Greek Girl to another impresario. To his satisfaction, it was a success, running for a year.

Max Steiner’s London Career

The success of The Beautiful Greek Girl led to a number of conducting opportunities abroad.

A British production invited him to conduct The Merry Widow, an operetta by his father’s former colleague Franz Lehár.

Steiner moved to London and stayed there for eight years, conducting The Merry Widow and other operettas.

Escape to New York

Max Steiner

However, the onset of World War I brought his career to a screeching halt. Britain declared war on Austria in August 1914. Steiner was twenty-six years old.

Because of his nationality, he was interned in Britain as an enemy alien. He was only released because of his friendship with the Duke of Westminster.

Despite that friendship, he was ultimately ejected from Britain and his scores compounded, ending up in New York City with just $32 to his name.

A Broadway Career, and a Start in Film

Steiner soon found work on Broadway, orchestrating, arranging, and conducting. He conducted works by George Gershwin, Jerome Kern, Victor Herbert, and others.

He began watching the development of the nascent movie industry with great interest, speaking to studio founders and directors about the potential of music to accompany silent films.

In 1927, he orchestrated and conducted a Broadway musical by composer Harry Tierney. When Tierney was hired by RKO Pictures, he urged the studio to hire Steiner, too.

At the time, the potential of movie music was yet to be fully understood. It was thought by studio heads that soundtracks should come from a library of cheap pre-recorded tracks, as opposed to being written for specific films (an idea that Steiner would push back hard against). Steiner was hired as the head of the music department at RKO, but only on a month-to-month contract.

He scored Dixiana, the Western Cimarron, and Symphony of Six Million. Symphony of Six Million, with its extensive score, was a landmark in cinema history, and it helped to convince film executives of the impact that a soundtrack could have on a movie.

Max Steiner’s Hollywood Career

King Kong

Throughout the 1930s, Steiner was on the front lines of establishing the language of movie music, influenced by figures like Richard Wagner and Richard Strauss.

He scored King Kong in 1933, finishing the iconic score in a jaw-dropping two weeks. It has often been called the most influential soundtrack of all time, demonstrating for executives, producers, and audiences once and for all what exactly a custom-written score could do for a movie.

Steiner relied on the Wagnerian idea of leitmotif, i.e., playing specific themes during the appearance of specific characters or ideas.

King Kong (1933) – Beauty Killed the Beast Scene

He also composed for and conducted many of the Astaire/Rogers musicals.

In 1937, Steiner was hired by Warner Bros, where he continued his extremely productive output.

Scoring Gone With the Wind

Gone With the Wind

In 1939, Steiner was hired by Selznick International Pictures to score Gone With the Wind.

He composed the score to the nearly four-hour film in three months. At the same time, in the year 1939, he composed the score for twelve other films.

Producer David O. Selznick had concerns that Steiner wouldn’t be able to finish in time, so he hired Franz Waxman to write a backup score.

However, it wasn’t needed. Steiner ended up delivering by working twenty-hour days, aided by prescribed injected amphetamines. He also had the assistance of four orchestrators.

Today, it’s widely regarded as one of the greatest film scores of all time.

Max Steiner’s Academy Awards

Gone With the Wind didn’t win an Academy Award for best score (it lost out to The Wizard of Oz), but over the course of his career, Steiner would win multiple Oscars.

In 1936, he won for his score to the thriller The Informer. In 1943, he won another for the drama Now, Voyager, and yet another in 1945 for the wartime drama Since You Went Away.

Other classics that he scored during this time include Casablanca, The Big Sleep, Mildred Pierce, and others.

Max Steiner’s Late Career

During the 1950s, changing tastes in movie music meant that Steiner’s lush, operatic style began to fall out of fashion.

He had one last major triumph with the theme for A Summer Place in 1959, which spent nine weeks at number one in 1960. It beat out Ray Charles, Ella Fitzgerald, Elvis Presley, and Frank Sinatra at the Grammys for Record of the Year.

Sadly, his health and vision began deteriorating later in life. He died of congestive heart failure in 1971 at the age of 83.

Max Steiner’s Innovations

Steiner was one of the first composers to employ a measuring machine to guarantee exact timings in a score. Before him, most composers just used a stopwatch, but Steiner felt it was important to sync his score with the film more closely than a watch’s second hand would allow.

He was also among the first to embrace click tracks. A click track consists of a series of holes punched into soundtrack film, creating a metronomic effect. Headphones can then be used and instruments played along to an exact tempo.

Throughout his career, he was on the cutting edge of developing ideas and principles about what scenes should and shouldn’t have music in them, as well as how loud music should be relative to dialogue.

He was also fascinated by the power of diegetic music (i.e., music that is played within the scene, that the characters also hear). Think of the famous renditions of “La Marseillaise” or “As Time Goes By” in Casablanca.

Max Steiner’s Modern Influence

Max Steiner conducting the score of King Kong

Steiner’s influence continues even today.

John Williams has cited him (as well as Steiner’s compatriot Erich Wolfgang Korngold) as a major influence, as has James Newton Howard, who scored the 2005 remake of King Kong.

He also pushed for film composers to earn residuals, helping to create an expectation that composers would be fairly compensated for their work.

It’s clear that for as long as movies exist, Max Steiner’s influence will continue to be felt.

Which Composer Wrote the Most Symphonies Ever?

by Emily E. Hogstad

Today we’re going to talk about symphonies.

What exactly is a symphony? Is it different from a sinfonia?

And, depending on your answer to that question, which composer has written the most symphonies of all time? And how many symphonies did that person write?

Keep reading to find out. The answers might surprise you!

Joseph Haydn (1732–1809)

104 Symphonies

Joseph Haydn

If you love classical music, you know Haydn would be on this list!

Joseph Haydn was born in rural Austria in 1732. He went on to become one of the most celebrated composers of the Classical era.

A major part of his reputation rests on his output of symphonies.

He wrote his first surviving symphony in 1759. Haydn’s First is in three movements: a slow movement bracketed by two fast movements. A typical performance takes about fifteen minutes.

He wrote his final symphony, numbered 104 and nicknamed the London, in 1795. This symphony demonstrates how far Haydn pushed the boundaries of the genre over his career.

The work has four movements (Adagio-Allegro, Andante Minnuet and Trio, and a finale marked “Spiritoso”) and takes about half an hour to perform.

Nowadays, we think of a symphony as a four-movement work for orchestra, at least half an hour in length. Haydn’s creative evolution over the course of writing a hundred-plus symphonies contributed to that perception.

Christoph Graupner (1683–1760)

113 Sinfonias

Christoph Graupner

Of course, Haydn’s development also leaves us with the question: should early orchestral sinfonias that aren’t as long as later symphonies count?

Music historians can argue the question, but for the purposes of this article, we’re going to say yes!

That’s why the next figure on our list is Christoph Graupner, who was born in 1683 (three years after Bach) in Saxony. He studied law in Leipzig, then music with Johann Kuhnau. Kuhnau was the music director of the renowned Leipzig-based Thomanerchor choir before Bach took the job.

Graupner spent most of his career at the court in Hesse-Darmstadt, where he worked between 1709 and 1754, when he went blind.

He wrote 113 sinfonias.

Here’s a recording of a particularly striking example. It’s a six-movement work composed for orchestra and six timpani.

Derek Bourgeois (1941–2017)

116 Symphonies

Derek Bourgeois

Derek Bourgeois was a British composer born in 1941. He studied at Cambridge and the Royal College of Music.

Early in his career, he worked as a lecturer, youth orchestra conductor, and director of music at St. Paul’s Girls School in London. He also composed extensively and was especially noted for his works for brass and wind band.

He wrote his first symphony when he was eighteen, in 1959. He had seven to his name by 2001, when he retired.

However, during retirement, he kept composing. By 2009, he revealed in an interview with The Guardian that he was up to 44 symphonies. That marked him as the most prolific symphony writer in British history.

And these works weren’t short, either. That Guardian article reported: “The average length of a Bourgeois symphony is 47 minutes.”

Remarkably, as he grew older, he only became more prolific. Between 2009 and his death in 2017, he added a shocking 72 more to his tally, for a grand lifetime total of 116!

Carl Ditters von Dittersdorf (1739–1799)

120+ Symphonies

Carl Ditters von Dittersdorf

Composer Carl Ditters von Dittersdorf was born Johann Carl Ditters in Vienna in 1739.

As a child, he studied the violin and eventually became a professional violinist. In 1771, he became the court composer at Château Jánský Vrch, in the present-day Czech Republic.

He was eventually promoted and received the noble title that transformed his name to Carl Ditters von Dittersdorf.

Dittersdorf wrote around 120 symphonies. Interestingly, he wrote twelve programmatic symphonies before the concept was popular, all inspired by Ovid’s Metamorphoses. Unfortunately, only half of them survive today.

Johann Melchior Molter (1696–1765)

140+ Symphonies

Johann Melchior Molter

Johann Melchior Molter was born near Bach’s hometown of Eisenach, sixteen years after Bach.

Much like Bach, records about Molter’s early training are scarce. Historians do know that by his early twenties, he had left Eisenach to take a job as a violinist in Karlsruhe.

Soon after, he decided to travel to Italy to continue his music studies. He lived there for two years, then returned to Karlsruhe, where he became Kapellmeister at the court there. In 1734, he accepted a job as Kapellmeister at the court of Duke Wilhelm Heinrich of Saxe-Eisenach.

Over the course of his career, he wrote 140+ symphonies and sinfonias.

These were written before Haydn and his generation revolutionised the genre, so most of them are only around ten minutes long and don’t adhere to the symphonic form as codified in the Classical era.

Still, this is exciting, attractive, striking music.

František Xaver Pokorný (1729–1794)

140 Symphonies

František Xaver Pokorný

František Xaver Pokorný was born in the town now known as Stříbro, Czech Republic.

He left to take lessons in Regensburg in present-day Germany. During the 1750s, he worked and studied in the cities of Wallerstein and Mannheim (where the virtuosity of the court orchestra would inspire a variety of eighteenth-century composers).

In the later part of his life, Pokorný returned to work at the court of Regensburg.

It is believed that over the course of his career, he wrote over 140 symphonies. However, after Pokorný died in Regensburg, fellow composer and court orchestra intendant Theodor von Schacht erased Pokorný’s name from his works and reattributed them to other composers, making certain identification difficult.

And without further ado, here is the composer who has written the most symphonies ever, by far…

Leif Segerstam (1944–2024)

371 Symphonies

Leif Segerstam

Leif Segerstam was born in Vaasa, Finland, in 1944. His family moved to Helsinki when he was a boy, and he studied violin and conducting at the Sibelius Academy there. He then finished his studies at Juilliard in the United States.

Between 1995 and 2007, he served as conductor of the Helsinki Philharmonic Orchestra. He also enjoyed an international conducting career.

Segerstam also composed and became famous for his 371 symphonies.

His first symphony – subtitled “Symphony of Slow Movements” – was written in the late 1970s. Beginning in 1998 with his 23rd symphony, he started writing multiple symphonies a year until 2023, ending with a grand total of 371.

Most of these symphonies last for around twenty minutes and are one movement long. Many feature unusual titles like “Symphonic Thoughts after the Change of the Millenium No. 1”, “Listening to the tree clapping your shoulder…”, and “Calling the 112 in woody galaxies of the multiverses….”

.jpg)