It's all about the classical music composers and their works from the last 400 years and much more about music. Hier erfahren Sie alles über die klassischen Komponisten und ihre Meisterwerke der letzten vierhundert Jahre und vieles mehr über Klassische Musik.

Total Pageviews

Sunday, December 10, 2023

The Most Beautiful "O Holy Night" - Sister Duet - Lucy & Martha Thomas

AUDIOJUNKIE: 'One Christmas': Palarang bituin

AT A GLANCE

Originally, “Kumukutikutitap” was written for a musical called “Bituin (The Star Of Bethlehem)” by Cayabyab with Jose Javier Reyes’ lyrics and was supposed to be used as a contest piece for a big choral competition back in 1983 that got canceled due to the aftermath of the Ninoy Aquino assassination.

National Artist for Music Ryan Cayabyab’s Pinoy yule classic “Kumukutikutitap” returns and makes its much-awaited debut on streaming platforms with the release of the “One Christmas” album.

As one of the most adored Pinoy Christmas songs ever, it’s hard to believe this tune has been missing in action on music streaming platforms until now.

Originally, “Kumukutikutitap” was written for a musical called “Bituin (The Star Of Bethlehem)” by Cayabyab with Jose Javier Reyes’ lyrics and was supposed to be used as a contest piece for a big choral competition back in 1983 that got canceled due to the aftermath of the Ninoy Aquino assassination.

The song then found its way into a fund-raising event where it was sung by The Singers’ Foundation choir, which included some of the biggest OPM acts as its members at the time. As recounted by Mr. C in an interview after its debut, all the choirs that heard “Kumukutikutitap” asked for its choral score. Ever since, the song, with its trademark a cappella arrangement, has become a staple of choirs’ Christmas setlists every Yule season.

However, singer Joey Albert first recorded and released it in 1984. And while her take was equally cheery, her version had instrument accompaniment.

It took the future National Artist seven more years before he recorded it for “One Christmas” (released in 1991 under the Telesis Recording label). This record served as the Cayabyab’s follow-up to his successful solo album “One.” And just like the latter record where Cayabyab is the single performer of all the vocals he also arranged, he did the same for “One Christmas.”

“Kumukutikutitap” is a bouncy tune that starts off with an instrumental nod to another enduring Pinoy carol in “Pasko Na Naman Muli” before it turns into an a cappella affair as the main song kicks in. The all-vocal style is a Cayabyab trademark by this time and his arrangement on this one easily shows why he’s a master.

And this is just one of the many highlights on said album.

The Cayabyab-written “Heto Na Naman,” “Ano’ng Gagawin Mo Ngayong Pasko” (with its “Pasko Na Naman” nod) and the lovely “Miss Kita Kung Pasko” are easy favorites and mixed with old favorites such as “Ang Aking Pamasko” by Antonio Velarde and Levi Celerio, “Noche Buena” by National Artists De Leon and Celerio, “Maligayang Pasko at Masaganang Bagong Taon” a.k.a. “Ang Pasko ay Sumapit” by Vicente Rubi and Celerio, “Himig Pasko” by S.Y. Ramos, and “Payapang Daigdig” also by De Leon.

These, plus a “Pasko Na Sinta Ko” cover complete the collection. “One Christmas” was produced for Telesis by Cayabyab and the late Margot M. Gallardo. It was recorded at the now-defunct Greenhill Sound Productions studio and sound-engineered by Monching Payumo.

“One Christmas” was almost relegated to analog obscurity if not for the recent acquisition of its distributor Ivory Records by Viva Music, which has now made it easily available on all digital platforms.

So, if you’re thinking of rehashing the same old Christmas songs this Yule season, you’re better off dusting these holiday classics instead. And not just anybody’s cranked-to-death Yule tunes, but a whole record’s worth of Pamasko-themed songs from Ryan Cayabyab himself.

“Koronahan mo pa nang palarang bituin!”

Saturday, December 9, 2023

First Concert of the Philharmonic Society of New York 7 December 1842

by Georg Predota, Interlude

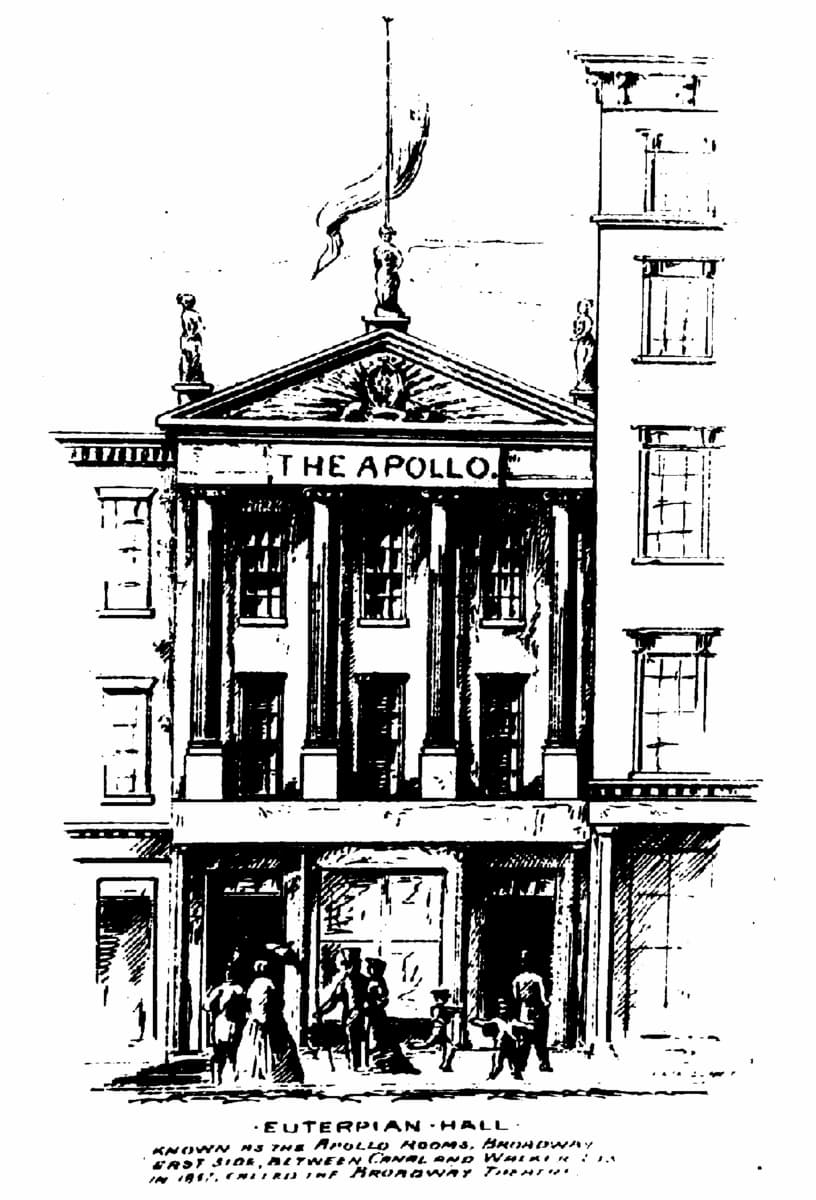

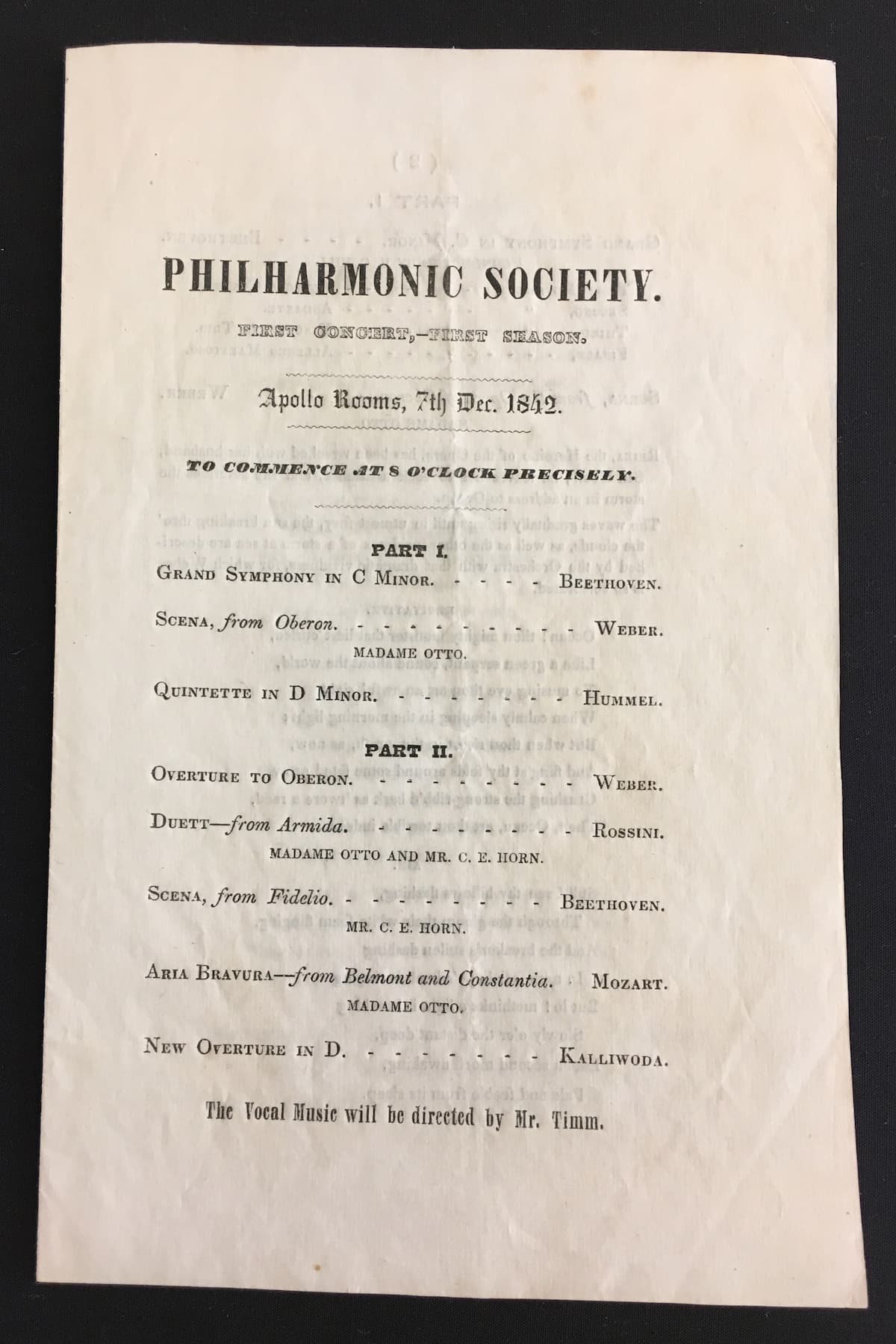

A momentous occasion took place on 7 December 1842 in the Apollo Rooms on lower Broadway. On that day, 600 audience members witnessed the first concert of the Philharmonic Society of New York.

The Apollo Rooms in New York

Formed as a cooperative organization of about 45 musicians and led by American-born violinist and conductor Ureli Corelli Hill, the principal aim of the society was “the advancement of instrumental music.” Today the orchestra is better known as the New York Philharmonic Orchestra (NYPO), and we thought it might be fun to recreate an abridged version of that first performance.

The programme for this opening concert was decided upon by a majority vote by the musicians of the orchestra. This performing cooperative also decided who would perform, and who among them would conduct. And at the end of the season, the players would divide the proceeds among themselves.

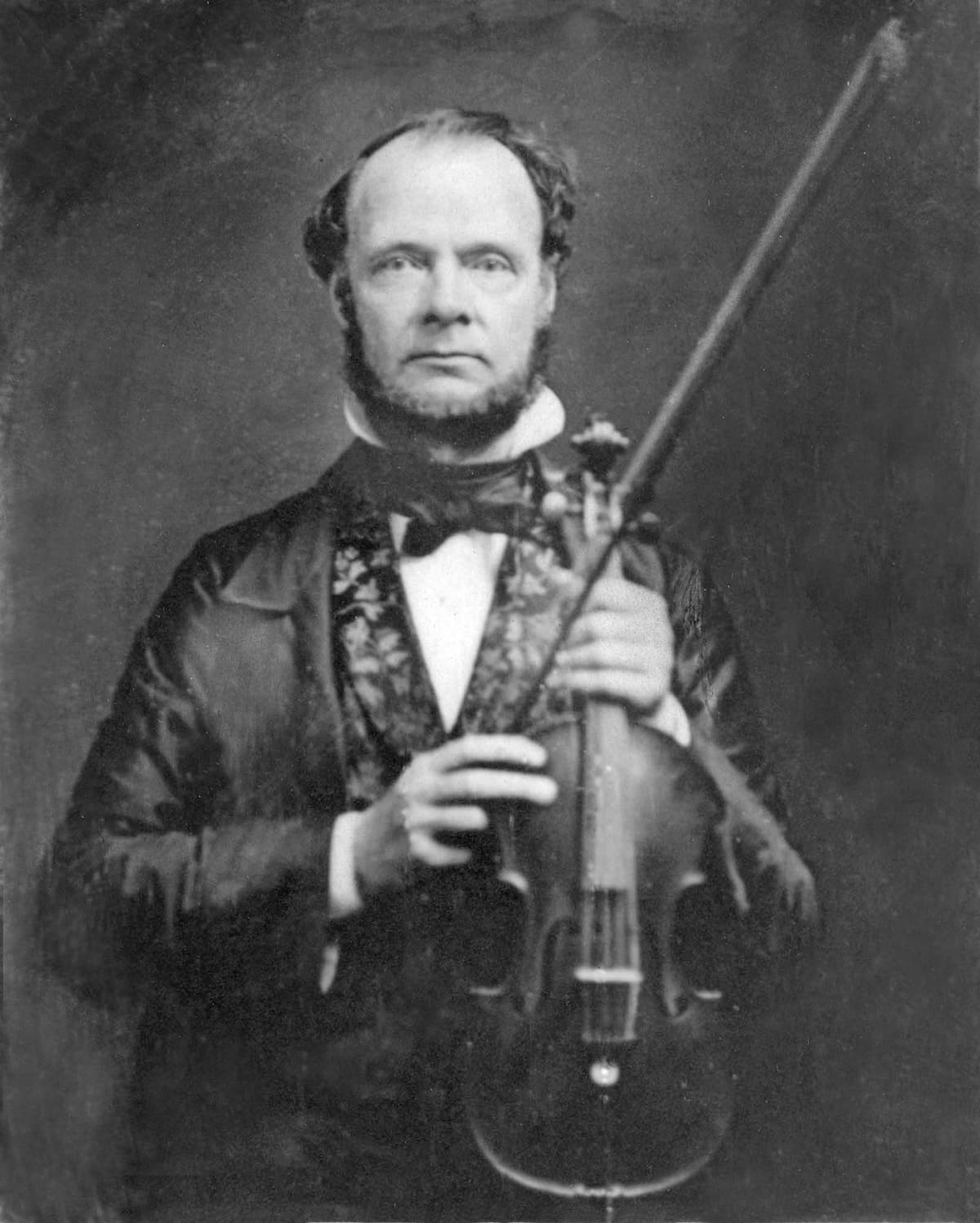

Ureli Corelli Hill

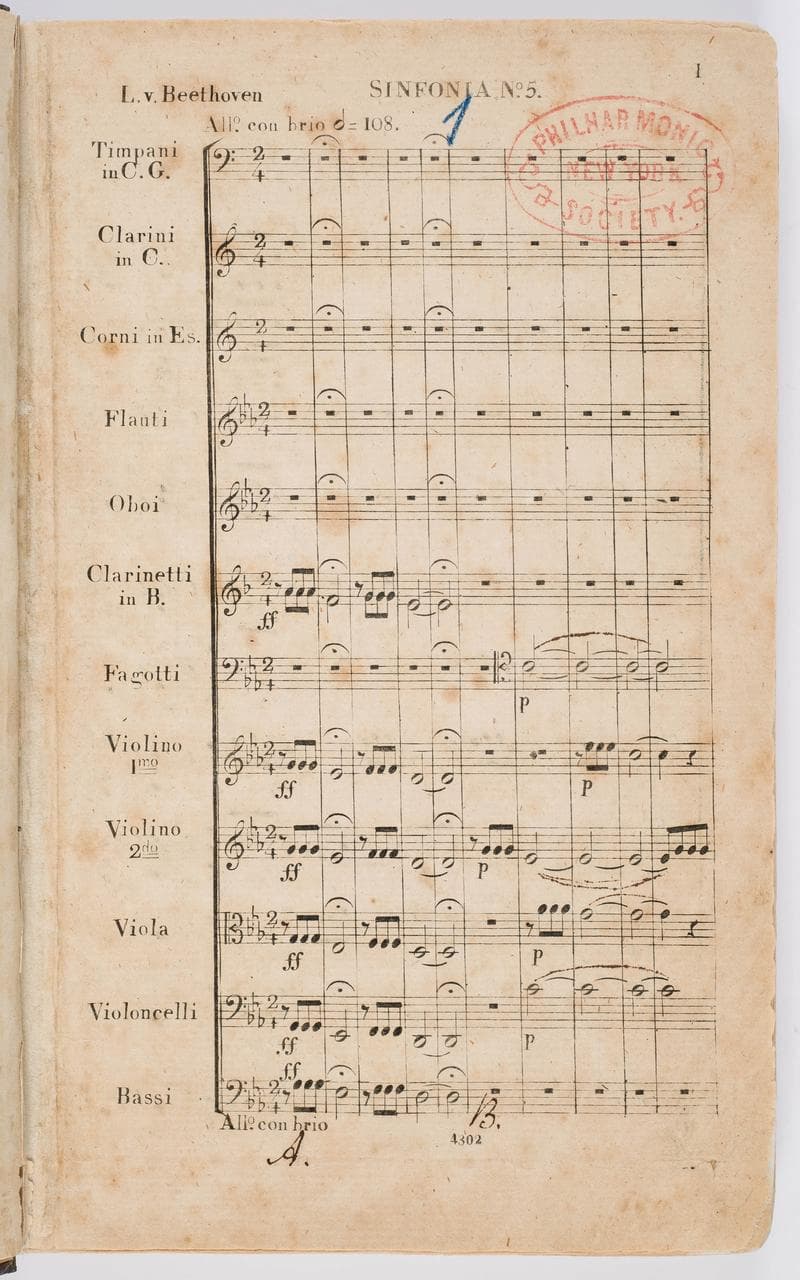

It all opened with Beethoven’s Symphony No. 5, led by Ureli Corelli Hill himself. Hill hailed from Connecticut, and his father was a music teacher and composer. He became the conductor and violinist of the New York Sacred Music Society, and he guided the first American performance of Mendelssohn’s St. Paul. Hill went to Germany to study with Louis Spohr, and organized the New York Philharmonic Society after his return to the States.

Carl Maria von Weber: Oberon, Act II “Ocean! Thou mighty monster”

The music score copy of Beethoven’s Symphony No. 5 used at the inaugural concert

Concert programmes during the mid-19th century were rather eclectic affairs and included chamber music and several operatic selections featuring a leading singer of the day. And audiences got their money’s worth, as concerts of this nature tended to run between 3 and 4 hours. As such, the second selection on that opening programme belonged to Carl Maria von Weber, and an excerpt from his opera Oberon.

The selection is taken from the second act of the Opera, when the heroine Reiza has been left alone and shipwrecked. As her husband has left her to find assistance, she describes the storm in an address to the Ocean. This selection was presented by Madame Otto, who as a critic writes, “has a lovely voice but must allow that she needs the knowledge to direct its use, the taste to render it effective, and the warm and earnest feeling which carries conviction to the heart of the listeners.”

Johann Nepomuk Hummel: Quintet in D minor, Op. 74a

Madame Antoinette Otto was highly active on New York stages during the 1840s. She was part of the operatic corps of the Park Theatre, and as she was married to Henry Otto, a founding member of the New York Philharmonic, she prominently featured in its opening programme. Otto would subsequently be one of the soloists in the Philharmonic’s 1846 American premiere of Beethoven’s Ninth Symphony.

Philharmonic Society of New York first concert program

The first part of the inaugural concert of the New York Philharmonic concluded with a performance of Hummel’s Quintet in D minor, Op. 74a. Originally composed in 1816 as a Piano Septet, the work adheres to the Viennese classical style, but Beethoven’s influence is heard in the stormy character of the music. Hummel added his own personal pianism of unprecedented virtuosity and brilliance, and Ureli Corelli Hill was part of the performing ensemble.

For the opening number of the 2nd part of the Programme, the Oberon Overture by Carl Maria von Weber, Denis-Germain Étienne took up the baton. He was a pianist, composer and horn player who had graduated from the Paris Conservatoire with a number of prizes. Étienne immigrated to the United States in 1814 or 1815, and performed in various American cities before settling in New York. He was chosen to be the permanent conductor of the newly founded Philharmonic Society in 1824, and he played both piano and French horn in the Philharmonic Symphony Society.

Immediately following this rousing opener of the second half, audiences were treated to the famous Duet “Amor! Possente nome” from Rossini’s opera Armida. Set during the first crusade near Jerusalem, the sorceress Armida is determined to weaken the Crusaders by dazzling the best soldier Rinaldo with her beauty. However, Armida has secretly fallen in love with Rinaldo, and she confronts him. When she accuses him of ingratitude, he admits that he’s in love with her as well.

Charles Edward Horn

For the Armida duet, Madame Antoinette Otto was joined on stage by the English composer and singer Charles Edward Horn. Horn gave his singing debut in 1809 in a comic opera at Lyceum Theatre, London. He rose to prominence with his portrayal of Caspar in the English version of Weber’s Freischütz, and soon also started a career as a composer. In one instance, he was accused of plagiarism but acquitted in court.

Horn first sailed for New York City in 1827 and made a successful American impression in works by Storace, Weber, Mozart, and Rossini. He did return to England to serve as music director of the Olympic Theatre from 1831 to 1832, before returning to New York.

Horn took on the directorship of Park Theatre, producing and directing performances of his own works and arrangements of works of others. His oratorio The Remission of Sin of 1835 may well been the first oratorio composed in the United States. Horn lost his voice due to illness and became active as a vocal coach.

Luckily, Horn found his voice again, and he now took the solo stage at the first concert of the Philharmonic Symphony Society of New York in the role of Florestan in Beethoven’s Fidelio. At the beginning of Act 2, Florestan is alone in his cell, deep inside the dungeons. He knows who is responsible for his incarceration, and sings of his trust in God, and then has a vision of his wife Leonore coming to save him.

Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart: The Abduction from the Seraglio, “How I loved him, I was happy”

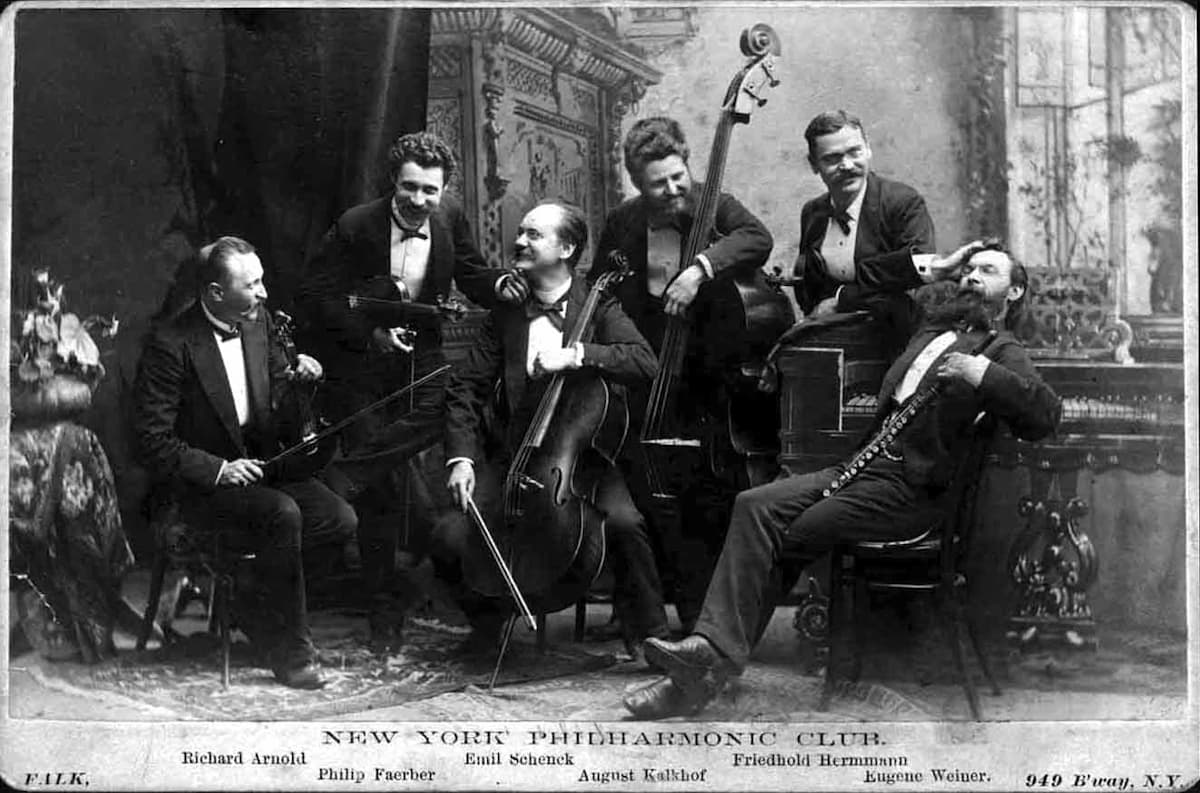

New York Philharmonic Club Chamber Ensemble

Charles Edward Horn eventually decided to retire in Boston. He was quickly elected director of the Handel and Haydn Society, and Madame Antoinette Otto was a frequent performer. She again took to the solo stage in the aria “How I loved him,” from Mozart’s Abduction from the Seraglio. As was customary at that time, portions of the libretto were printed in the playbill.

Alas, I loved,

I was so happy;

I knew nothing of love’s pain.

Promised to be true

To my beloved,

And I gave him all my heart.

But how quickly my joy deserted me,

Separation was my unhappy fate.

And now my eyes are bathed in tears,

Grief resides in my breast.

Johann Wenzel Kalliwoda: Overture No. 12 in D Major, Op. 145

Johann Wenzel Kalliwoda

To conclude the first concert of the Philharmonic Society of New York, the orchestra decided to perform a newly composed overture by Johann Wenzel Kalliwoda. Kalliwoda seems an interesting choice for us today, but in his day he was described as “a master of the first rank.

Many-sided, sure of himself in every field, often new and original and yet natural and simple, he repeatedly makes the impression of a choice talent and nears the final stage on the way to immortality.”

This final selection, and all the vocal numbers, were conducted by Henry Christian Timm, a German-born American pianist, conductor, and composer. Timm worked in New York City as a concert pianist, teacher, organist, and chamber musician. He served as the president of the city’s Philharmonic Society from 1847 to 1864. Kalliwoda and Timm seemingly did not achieve immortality, but the New York Philharmonic Orchestra probably did. They were certainly off to a great start.

Thursday, December 7, 2023

Kaija Saariaho - her music and her life

The composer Kaija Saariaho has died at the age of 70. As a tribute we republish an overview of her life and career by Guy Rickards from April 2013 below. And, as a preface, we have James Jolly's recent interview with Saariaho (for medici.tv) filmed earlier this year:

Kaija Saariaho (b1952 in Helsinki) is one of the foremost women composers on the planet and one of the leading creative figures of her generation of either gender; a truly original artist with a very distinctive musical style and personal voice, developed and refined over decades. The awards she has received over the years are indicative of this, including the Kranichsteiner Prize (1986), the Nordic Council Music Prize (2000, for Lonh), the Grawemeyer (2003, for her first opera, L’amour de loin), the Nemmers Prize in Composition (2007), the Wihuri Sibelius Prize (2009) and the Léonie Sonning Music Prize (2011).

Yet she is also a very private person, with much about her biography that is largely unknown, not least that she was born Kaija Laakkonen: the ‘trademark’ name of Saariaho is her first husband’s. She studied with Heininen at the Sibelius Academy, with other members of a miraculous generation of Finnish composers including Esa-Pekka Salonen and Magnus Lindberg. Further studies followed with Brian Ferneyhough and Klaus Huber; equally formative influences were Tristan Murail and Gérard Grisey, the principal exponents of spectral music (music placing timbre and sound ahead of other compositional considerations), leading her to IRCAM and 30 years’ residence in Paris, latterly with her second husband, Jean-Baptiste Barrière. Although she made an initial breakthrough with the orchestral Verblendungen (1984), it was with her dazzling, enchanting nonet-with-electronics Lichtbogen (‘Arches of Light’, 1986) that she burst onto the wider scene. Its ethereal, hypnotic textures were inspired by the aurora borealis, and the use of electronics proved prophetic for her future career. More important still was the combination of sonic delicacy and an inner steel – which makes her works beguiling to the ear yet robust and compelling as structures.

Building on the success of Lichtbogen, Saariaho has composed a further 100-plus works for the widest variety of forces, from full-scale opera to instrumental solos. Yet Saariaho has fought shy of many of the standard Classical forms, such as sonata, symphony, trio and quartet. There are two unconventional works for string quartet, Nymphéa (subtitled Jardin secret III, with a large electronic component, 1987) and Terra memoria (2006), both later reworked for string orchestra (Nymphéa as Nymphéa Reflection in 2001). Her instrumental output includes many vivid works with illustrative titles, such as Io (1987), Solar (1993) and Orion (2002). Even in her concertos, the one conventional genre she has cultivated, the inner structures are highly unconventional, each work deriving its form from particular sound combinations or the nature of the instruments being written for (including the human voice). This was demonstrated early on in her hybrid orchestral diptych Du cristal… á la fumée (1989-90), where …á la fumée is a single-span double concerto for alto flute and cello, the concerto ‘form’ emerging out of the purely orchestral Du cristal.

Later concertos have followed highly individual and imaginative courses: Amers (1992, for cello), Graal théâtre (1994, for violin; also in a reduced arrangement, 1997), Aile du songe (2001, for flute – an instrument that features prominently throughout her catalogue) and, most recently, D’om le vrai sens, the clarinet concerto written in 2010 for Kari Kriikku. While timbre and the nature of sound, rather than established musical forms from the past, give Saariaho’s music its inner framework, the results are not haphazard or quixotic. Saariaho has used computer-driven analyses, sound patterns, chords or instrumental combinations to assist in selecting the appropriate structures for her music. While this might seem mechanical, almost an abdication of the composer’s primary role in creativity, in Saariaho’s case it is a liberating method, allowing her new means and avenues for her musical intuition to follow.

Expressivity is all, and this is nowhere more apparent than in the string of vocal works that she’s written since the late 1980s, such as Grammaire des rêves (1988), Nuits, adieux (1991), Lonh (1996), Oltra mar (1999), the oratorio La passion de Simone (2006) and Leino Songs (2007). The apex of her output, however, is undoubtedly her operas (all with librettos by Amin Maalouf), starting in 2000 with L’amour de loin, a powerful and mesmerising tale of unrequited, chivalric love set during the Crusades. This work has rightly garnered considerable acclaim, with two fine sound recordings (plus one on DVD) bringing Saariaho to the attention of a still wider audience. Two further operas, Adriana mater (2005) and Emilie (2008), have refined her operatic sensibilities further, but it is L’amour that remains the pivotal work in her output, a fact Saariaho herself acknowledges: ‘Everything I had written up to that moment was in that piece. All the material, my approach to harmony, to texture – all of it was there. And so after the opera, I somehow felt that I was starting again.’