It's all about the classical music composers and their works from the last 400 years and much more about music. Hier erfahren Sie alles über die klassischen Komponisten und ihre Meisterwerke der letzten vierhundert Jahre und vieles mehr über Klassische Musik.

Total Pageviews

Tuesday, May 31, 2022

Jacques Ibert - his music and his life

Sunday, May 29, 2022

Germaine Tailleferre - her music and her life

Born in Paris on April 19th 1892, French composer Germaine Tailleferre began her studies at the Paris Conservatory in 1904, despite her father’s opposition and her equal ability in art. She studied primarily with Eva Sautereau-Meyer. She was a pianistic prodigy with a phenomenal memory for music which led to her winning many prizes. In 1913, she met Auris, Honegger and Milhaud whilst studying in Georges Caussade’s counterpoint class. Eric Satie was so impressed by her 1917 work Jeux de plein air for two pianos that he described her as his ‘musical daughter’, and through this relationship, Tailleferre’s reputation was substantially advanced. When Les Six was formed in 1919-20, she became its only female member. Her abilities at the harpsichord and affinity for the styles of music originally composed for the instrument stood her in excellent stead as the neo-classicism of Stravinsky began to grow in popularity, though her works retained an influence of Fauré and Ravel.

Unfortunately, Tailleferre’s circumstances in through much of the rest of her life meant that she never gained much of the same acclaim as the other members of Les Six. After two very unhappy marriages, she found her creative energies drained and due to financial issues was almost unable to compose if not for commission, leading to many uneven and quickly composed works. Moreover, her lack of self-esteem and sense of modesty held her back from publicising herself to a fuller extent. In spite of this, some of concerti of the 1930s saw some success and she was often approached to compose for film. Throughout her career she continued to compose music for children which some writers have suggested helped to retain the spontaneity, freshness and charm that characterises her finest works.

Saturday, May 28, 2022

Darius Milhaud - his music and his life

Darius Milhaud (4 September 1892 – 22 June 1974) was a French composer and teacher. He was a member of 'Les Six' and one of the most prolific composers of the twentieth century. His compositions are influenced by jazz and make use of polytonality.

Milhaud studied at the Paris Conservatory where he met his fellow group members Arthur Honegger and Germaine Tailleferre. Milhaud (like his contemporaries Paul Hindemith, Gian Francesco Malipiero, Bohuslav Martinů and Heitor Villa-Lobos) was an extremely rapid creator, for whom the art of writing music seemed almost as natural as breathing. His most popular works include Le bœuf sur le toit (ballet), La création du monde (a ballet for small orchestra with solo saxophone, influenced by jazz), Scaramouche (for Saxophone and Piano, also for two pianos), and Saudades do Brasil (dance suite).

His autobiography is entitled 'Notes sans musique' (Notes Without Music), later revised as 'Ma vie heureuse' (My Happy Life). The Milhaud family left France in 1939 and emigrated to America in 1940 where he secured a teaching post at Mills College in Oakland, California. From 1947 to 1971 he taught alternate years at Mills and the Paris Conservatoire, until poor health compelled him to retire. He died in Geneva aged 81.

Friday, May 27, 2022

The Greatest Composers of Film Music

Satie, Ibert, Tailleferre, Milhaud and Honegger

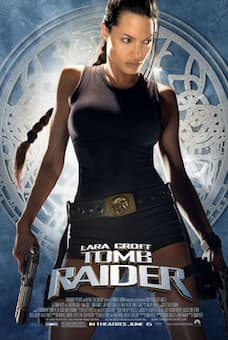

Tomb Raider

I was still too young to actually see the first “Tomb Raider” film release in 2001. But when I first watched it some years later, I thought it was the biggest thing since the invention of the handbag. Finally, there was an empowered women beating up all those macho male characters. Later I played all the video games, and “Lara Croft” became a cultural phenomenon that is still going strong 25 years later. Basically, they are pretty silly movies but you can’t beat swashbuckling action films if you want to enjoy a couple hours of mindless fun. The Hollywood studios have given us countless action/adventure movies, and that formula has been a huge commercial success. No wonder that they called the 1930’s Hollywood’s Golden Age. In Europe meanwhile, audiences had little taste for blowing up the world movies after World War I, so filmmakers tended to focus more on the artistic qualities of film. While American composers of film music “seemingly held that new medium in distain,” they imported the Viennese composers Max Steiner and Wolfgang Eric Korngold. In Europe meanwhile, a significant number of art music composers embraced this new challenge. In France, in particular, a number of big-name composers eagerly adopted the new art form, including Erik Satie, Jacques Ibert, Germaine Tailleferre, Darius Milhaud, and Arthur Honegger.

Erik Satie & Francis Picabia, Jean Biorlin (prologue de Relache)

When eccentricity and classical music are used in the same sentence, Erik Satie (1866-1925) immediately comes to mind. Irreverent, disrespectful, contemptuous of tradition, forcefully direct and brutally honest, Satie famously wrote underneath his self-portrait, “I have come into the world very young, into an era very old.” In 1924, Satie collaborated on a ballet production with Francis Picabia, and since both artists had a taste for controversy, audiences immediately knew what to except. It was called Relâche, loosely translated into “No Performance today,” or “Theatre Closed,” and it had really no plot. A female character dances with a changing number of male characters, including a paraplegic in a wheelchair. And there is a man dressed as a fireman who wanders around the stage, pouring water from one bucket into another.

Relâche Part 1

Between acts and after the overture, the film “Entr’acte” was shown. An experimental film by critic Rene Clair, it featured scenes filmed in Paris that included a dancing ballerina with moustache and beard, a hunter shooting a large egg, and a mock funeral procession with a camel-drawn hearse. Satie composed the music for both the ballet and the film, and his score for “Entr’acte” was called revolutionary. “It is an excellent example of early film music, as different segments reflect and support the rhythm of the action and serve as a kind of neutral rhythmic counterpoint to the visual action.” Satie used a number of popular tunes, and while the ballet is little more than nonsensical fragmented spectacle to make Dada proud, “the music is essentially unified and symmetrical.” The premiere, as you might expect, did not go well and audiences and critic attacked “the stupidity of the staging and the inanity of the musical score.” Today we recognize it “as an inventive score without peer, at once durable and distinguished, with “Satie having understood correctly the limitations and possibilities of a photographic narrative as subject matter for music.”

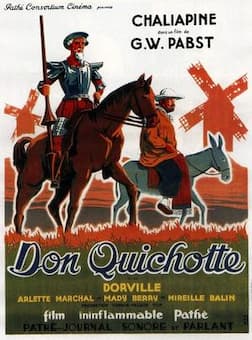

Jacques Ibert: 4 Chansons de Don Quichotte

Don Quichotte

I have always loved the music of Jacques Ibert (1890-1962) because he doesn’t take himself or classical music all too seriously. He once said that he only agreed to write music that he was happy to listen to himself. “I want to be free,” he writes, “independent of the prejudices which arbitrarily divide the defenders of a certain tradition, and the partisans of a certain avant garde.” His biographer writes, “Ibert’s music can be festive and gay…lyrical and inspired, or descriptive and evocative…often tinged with gentle humour.” That’s a perfect recipe for writing incidental music for the theater and music for film. In fact, Ibert was a prolific composer when he came to cinema scores, writing music for more than a dozen French films, and two pictures for American directors Orson Welles and Gene Kelly. In 1933, Georg Wilhelm Pabst, one of the most influential German-language filmmakers during the Weimar Republic, directed Don Quixote, the film adaptation of the classic Miguel de Cervantes novel. It was made in three versions—French, English, and German—and featured the famous operatic bass Feodor Chaliapin. The producers separately commissioned five composers—Ibert, Ravel, Delannoy, de Falla, and Milhaud to write the songs for Chaliapin, each composer believing only he had been approached. Jacques Ibert’s music was selected for the film, and Ravel considered a lawsuit against the producers.

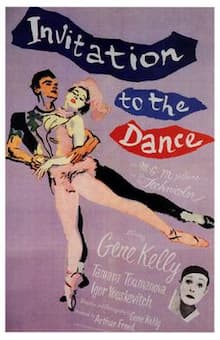

Invitation to the Dance

The American actor, dancer, and singer Eugene Kelly became incredibly famous for his performances in “An American in Paris,” and for “Singin’ in the Rain.” Kelly also starred in “Invitation to the Dance,” the first film he directed on his own. The film is a dance anthology that has no spoken dialogue, with the characters performing their roles entirely through dance and mime. The film consists of three distinct stories, written by Kelly, with the first segment “Circus” set to original music by Jacques Ibert. The plot is a tragic love triangle set in a mythical land sometime in the past. Kelly plays a clown, who is in love with another circus performer, played by Claire Sombert. She, however, is in love with an Aerialist, played by Youskevitch. The Clown, after entertaining the crowds with the other clowns, sees his love and the Aerialist kiss and wanders into a crowd in shock. That night he watches them dance together, and after the Lady finds him with her shawl, he confesses his love to her. The Aerialist finds them and thinks she has been unfaithful and leaves her. Determined to win her, the Clown tries to walk the Aerialist’s tightrope himself, only to fall to his death. Dying, he urges the two lovers to forgive each other. By the way, the movie was a colossal failure at the box office, but it is today regarded “as a landmark all-dance film.”

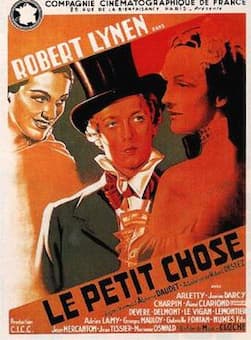

Le petit chose

Germaine Tailleferre (1892-1983) was the only female member of the French group of composers known as “Les Six.” She was well-known for her intimate chamber music compositions, but it is generally less well-known that she scored music for thirty-eight films! And that includes music for a series of documentaries, and a number of wonderful collaborations with film director and producer Maurice Cloche. His career spanned for over a half-century, and he produced spy thrillers and films with religious and social themes. He is probably best known for “La Cage aux Oiseaux” (‘The Bird Cage); “Le Docteur Laennec,” the story of the inventor of the stethoscope; “Ne de Pere Inconnu” (Father Unknown) and “La Cage aux Filles” (The Girl Cage). Cloche founded a film society for young talents in 1940, which later became the Institute of Advanced Film Studies and France’s leading film school. Cloche was part of a group of directors that focused on poetic realism, but he did not neglect social subjects. His most famous documentaries on art included “Terre d’amour,” “Symphonie graphique,” “Alsace,” and “Franche-Comte.” In 1938 Cloche turned the autobiographical memoir by Alphonse Daudet into the film Le Petit Chose (Little Good-for-Nothing) starring Arletty, Marianne Oswald, and Marcelle Barry. The title is taken from the author’s nickname, and “Little Good-for-Nothing” is forced to accept a job as a Latin teacher in a college. He is expelled for having naively trusted one of his colleagues, and he departs to join his brother in Paris where he is dreaming of great literary career. As an interesting side-note, the movie features 14-year-old classical guitarist Ida Presti in a supporting role as a guitar player. Tailleferre composed a wonderfully flowing film store that is at once “bold and original, dissonant and exploratory, vigorous and soothing.” In her day, Tailleferre was greatly admired for her film work, which was “likened to the wispy work of the popular watercolorist Marie Laurencin.”

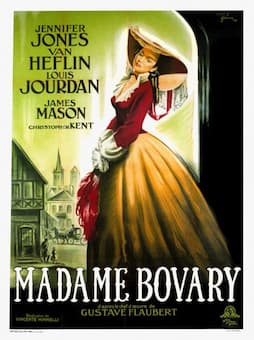

Darius Milhaud: L’album de Madame Bovary

Madame Bovary

Darius Milhaud (1892-1974) composed over 400 compositions during his life, and given his love of the cinema, he also wrote music for 25 films. It all started with his first major success, the 1919 Surrealist ballet “Le Boeuf sur le toit,” (The Ox on the Roof). That work was originally subtitled a “Cinéma-symphonie,” and it featured fifteen minutes of music “rapid and gay, as a background to any Charlie Chaplin silent movie.” Milhaud was already composing music in the silent era, “with the now lost score to accompany Marcel L’Herbier’s avant-garde melodrama “L’Inhumaine.” The music is said to have matched the “film’s abrupt, expressionist rhythm, climaxing—for a scene where the hero resurrects his dead love in a futuristic laboratory—in a bravura cadenza scored solely for percussion instruments.” Always eager to experiment, Milhaud brought the opera into the cinema, as he used a backdrop movie screen to disclose the thoughts of his characters in his opera Christophe Colombe. In Dreams That Money Can Buy of 1947, Milhaud collaborated with the Surrealist/Dada super stars Max Ernst, Marcel Duchamp, Man Ray, Alexander Calder, and Fernand Léger, and he received a visit from Renoir while he was composing the score for Madame Bovary.

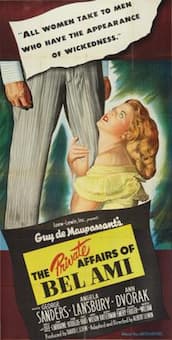

The Private Affairs of Bel Ami

Milhaud’s love for experimentation needed an eclectic use of music. He did admire Debussy and Mussorgsky but truly hated Wagner. Milhaud “happily threw in elements of whatever took his fancy—jazz, Brazilian dance rhythms, the medieval troubadour songs of his native Provence. Rather than cast his music in a predetermined style, he preferred to adopt whatever forms and materials seemed appropriate to the given task. This adaptability, together with his fluency of inspiration should have made him an ideal film composer. But his relationship with the movie industry remained oddly uneasy.” Milhaud spent much of his later life in America, but hated working for Hollywood. “He disliking the system of handing over the composer’s short score to professional orchestrators who churn out on a commercial scale musical pathos à la Wagner or Tchaikovsky.” He did, however, accept one Hollywood assignment titled The Private Affairs of Bel-Ami directed by Albert Lewin. Milhaud called him a “highly cultured man, and what is even rarer in those circles, genuinely modest.” Milhaud did orchestrate his own music, conducted the recording session and was present during the mixing. “The result was a score that vividly evoked the Paris of the Belle Epoque, but without the usual wash of romantic nostalgia.”

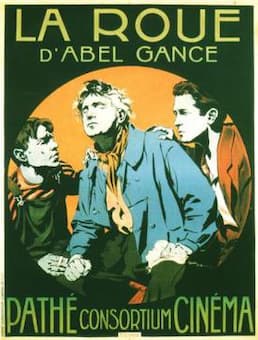

La Roue

Arthur Honegger (1892-1955) was critically acclaimed for both his concert music and his film scores during the interwar years in France. In terms of film scoring, Honegger is best remembered for his collaboration with Abel Gance, a pioneer film director, producer, writer and actor. Gance pioneered the theory and practice of montage, and he is best known for three major silent films J’accuse (1919), La Roue (1923), and Napoléon (1927). And Honegger wrote the music for all three silent films. J’accuse juxtaposes a romantic drama with the background of the horrors of World War I, and it is sometimes described as a pacifist or anti-war film. Work on the film began in 1918, and some scenes were filmed on real battlefields; can you imagine? The film’s powerful depiction of wartime suffering, and particularly its climactic sequence of the “return of the dead” made it an international success, and confirmed Gance as one of the most important directors in Europe. The only surviving score for the 1922 melodrama La Roue is an overture scored for medium-sized orchestra. There has been much speculation as to the rest of the music, and it is said “that Honegger put together a score consisting of pieces of his own and music from the classical repertoire.”

Arthur Honegger: Napoleon Suite

Albert Dieudonne as Napoleon_1927

Abel Gance’s silent masterpiece Napoleon of 1927 “exceeds the parameters of virtually every aspect of film culture. In the 1920s, its temporal gigantism horrified producers and its aesthetic invention flustered critics.” The film is recognised as a “masterwork of fluid camera motion, produced in a time when most camera shots were static. Many innovative techniques were used to make the film, including fast cutting, extensive close-ups, a wide variety of hand-held camera shots, location shooting, point of view shots, multiple-camera setups, multiple exposure, superimposition, underwater camera, kaleidoscopic images, film tinting, split screen and mosaic shots, multi-screen projection, and other visual effects.” It tells the story of Napoleon’s early years, and Gance had planned it to be the first of six films about Napoleon’s career, basically a chronology of great triumph and defeat ending in Napoleon’s death in exile on the island of Saint Helena.

Abel Gance and Arthur Honegger, 1926

Gance had struggled to make the first film, and given the enormous costs involved, he understood that the full project was impossible. Honegger believed that “cinematic montage differs from musical composition in that, while the latter depends on continuity and logical development, the film relies on contrasts. Music and sound must, therefore, adapt themselves to strengthening and complementing the visual element, while the whole must be an artistic unity.” Until now, the original cue sheet for Honegger’s music to Napoleon has not been found, so we don’t know exactly what music was played when. However, a number of musical autographs and orchestrated manuscripts have survived, and have been compiled into a wonderful Napoleon Suite sequence. There are so many more beautiful French movies and corresponding gorgeous music to explore, but in the next blog we will turn our attention to the two Russian giants Dmitri Shostakovich and Sergei Prokofiev.

Thursday, May 26, 2022

Britain’s Got Talent opera singer performs ‘Caruso’ and moves audience to tears

24 May 2022, 16:42 | Updated: 25 May 2022, 14:06

By Savannah Roberts, ClassicFM London

Here's the moment a young opera singer delivered a 1986 Italian love song famously performed by the likes of Luciano Pavarotti and Andrea Bocelli.

Maxwell Thorpe gave a hair-raising performance during his Britain’s Got Talent audition, surprising the crowd with the challenging number written by Lucio Dalla and dedicated to the prolific operatic tenor, Enrico Caruso.

Introducing his performance, the 32-year-old opera singer told the judging panel that he was “very nervous”.

“I’ll have to sing them [my nerves] out,” the northern singer announced to the audience.

Maxwell revealed that he had been busking in Sheffield for 10 years, and that in his experience he is “sometimes singing to people that aren’t listening.”

Read more: Incredible moment when ‘The X Factor’ vocalist sang both parts in soprano and tenor duet

The judges and audience were left stunned when Thorpe’s shy demeanour dropped, as soon as he began to sing. A moment of silence fell upon the stage as the melancholic melody came to a close, before the theatre responded with a well-earned standing ovation.

Simon Cowell showered the BGT hopeful with praise, saying: “You’re heading for the big time. Maxwell, that was extraordinary. Seriously, you’re so shy and quiet and then that happened.

“I thought that made it incredible,” Simon continued.

The reaction among the panel was unanimous, with Alesha Dixon professing: “Wow, wow, wow! The hairs on my arms stood up, literally as soon as you started.

Read more: When a 13-year-old operatic soprano stormed America’s Got Talent finals, and ignited a huge debate

“It just felt romantic and powerful and meaningful and all the feels.”

Amanda Holden praised the Sheffield singer further, saying: “I hope that going forward you feel more appreciated because these people were on their feet for you. I really hope that reaction has done something for your confidence as you are better than standing on a pavement.”

Maxwell received a yes from all four judges, who turned around in their seats to see an ecstatic audience behind them. Opera on a talent show? We’ve seen it before, but this is up there with the best...

Monday, May 23, 2022

AUDIO JUNKIE: Classical kick, Julio Nakpil style

by Manila Bulletin Entertainment

The music of Julio Nakpil, a Pinoy renaissance man, is the subject of an ongoing retrospective series titled “The Music of Julio Nakpil.”

The series has already released two robust collections namely “The Music of Julio Nakpil (1867-1960) Volume 1 & 2: Works for Piano.”

But as music masters go, two albums just won’t cover the works of a prime artist. Hence volumes III and IV: “Works for Voice and Chamber Ensemble” and “Works for Band and Orchestra” respectively.

But who is Julio Nakpil? And why do we care? Well, Nakpil is a composer out of the past. He was a revolutionary, a Katipunero—and a general at that—who fought against the Spanish in the Philippine Revolution of 1896 and has seen firsthand the tumult of the succeeding occupations of the Americans and the Japanese in the first half of the 20th century. But throughout, Nakpil managed to carve a body of work that is still celebrated today, more than a century and a half after his birth. And these collections are standing proof to his massive contribution to Philippine classical music.

Each record focuses on a different aspect of Nakpil’s works. “Volume III” in particular spotlights Nakpil’s “Works for Voice and Chamber Ensemble.” And “Amor Patrio! Romanza” for voice, oboe and piano” is just the ticket for those who lean toward vocal classical music. This moody piece demonstrates Nakpil’s flair for the dramatic and this century-plus old composition (written in 1893) is brought to life again by soprano Jasmin Salvo, with Mari Angeli Nicholas’ oboe and on piano, Dingdong Fiel.

And while the album opener and the segue piece “Il Ramento (The remembrance)” seem to be serious sonic excursions, the mood eventually lightens starting with the celebratory “Himno (Hymn).” The latter’s intro seems to be a nod to Mozart, but nonetheless stands on its own.

This and hymnals such as “Marangal Dalit bg Katagalugan (Hymno Nacional)” and the kundiman-like “Pag ibig (Love) Habanera” are sonic calling cards for sopranos Jasmin Salvo, tenor Radnel Ofalsa, and the UST choir Coro Tomasino. As the joyful “Luz Poetica de la Aurora” is for Reynato Resurreccion Jr.’s oboe. Volume III hotspot? “Danse Campestre: Habanera para concierto” with its classical romanticism and joyful cadence implied by Dingdong Fiel’s excellent piano work, as Christian Tan’s violin sings on top, easily takes the cake.

“The Music of Julio Nakpil Volume IV: Works for Band and Orchestra” meanwhile injects new vigor into the orchestral works of this Filipino music master. With the UST Symphonic Band and the UST Symphony Orchestra under the baton of Herminigildo Ranera breathing life into pieces (ironically) to the funereal “Sueño Eterno, Marcha Funebre” and “Pahimakas! (Last Farewell) Marcha Funebre.” The latter is dedicated to the memory (and last moments) of Rizal.

“Volume IV” is also festive and jovial as heard on “Biak Na Bato: Paso-Doble,” “Expocision Regional” and “Salve Patria! (Hail Motherland) Gran Marcha.” The last one was written by Nakpil to commemorate Rizal’s 8th death anniversary that coincided with the inauguration of the Rizal monument.

A project of the University of Santo Tomas Research Center for Culture, Arts and Humanities, and produced by Maria Alexandra Iñigo Chua, “The music of Julio Nakpil” is a definitive compendium of the works of a true Filipino music master.

Having said all that, It’s highly recommended to go back to Volumes I & II “Works For Piano” compositions written specially for the keyboard. Master pianist Raul Sunico performs all of Nakpil’s work and it is akin to hearing masters of two different era’s collaborating across time.

Truly world class all of them.

Friday, May 20, 2022

How Do Musicians Express Their Emotions through Music?

by Frances Wilson, Interlude

Music is a powerful means of communication, by which people share emotions, intentions, and meanings, and our personal engagement with music, whether in a live concert, listening to a CD or via a streaming service, is driven by the medium’s ability to convey and communicate emotion. Music can arouse strong feelings, recall memories; it can promote extreme happiness or engender feelings of deep love or loss…

Like speech, music has an acoustic code for expressing emotion, and even if a piece of music is unfamiliar, we can “decode” its message. Because of this, while musicians perform music according to their own interpretations, we can still understand the basic acoustic code: a crescendo indicates increased intensity or drama; a minor key suggests seriousness or melancholy; pauses create suspense and anticipation.

For the performer, the ability to communicate emotion, or tell a story, in music requires more than the technical facility to process what’s on the score. A good understanding of the structure of the music is important for a convincing, and communicative, musical performance, allowing the musician to respond to aspects such as variations in tempo and dynamics, harmonic and melodic tension and release, phrasing, repetitions, etc. By responding to these elements, the listener is given a set of musical “signposts” which guide them through the music, and bring cohesion, interest and variety to the performance.

A performer must resolve the entire depth of the ideas contained there. How often carefully notated shadings, accents, tempo changes reveal not simply a positive characteristic of sound but rather the untold sides of the author’s concept. How many directions we find in Schumann, Chopin, Scriabin, even Beethoven that a pianist should follow not in a real sound but by addressing the subtlest hints to the imagination of a listener!

– Samuil Feinberg

Communicating emotion is the most elusive aspect of the performer’s skillset, and is the fundamental reason why people – performers and listeners – engage with music. At a basic level, music communicates specific emotions through simple musical devices, for example:

- Happy – fast tempo, running notes, staccato, bright sound, major key

- Sad – very slow tempo, minor key, legato, descending sequences or falling intervals, diminuendo, ritardando

But there is something else which makes a performance particularly rich in expression or communication. Performance is generally regarded as a synthesis of both technical and expressive skills. Technical skills can be taught, while expression is more instinctive: it is of course possible to act upon expression markings in the score, but in order for these to sound convincing and, more importantly, natural, the performer must draw upon other factors, including extra-musical ones.

Many performers create a vivid internal musical and artistic vision of the music they are playing. This may include an aural model; the use of metaphors or adjectives to create a narrative or picture for the music; and personal experience, including extra-musical experiences. A performer’s own emotional experiences may influence the way they convey emotion in the music. This suggests that only a performer who has actually experienced the highs and lows of romantic love can perform, for example, Schumann’s Fantasie in C with the requisite emotional insight. Of course, not every performer will have the life experience, but they can still convey emotion in their performance by awakening their imagination to bring expression and emotional depth to their playing. In addition, in a concert situation, the imagination of the listener is very much at the disposal of the performer, to be shaped and influenced through sound.

We talk about performers “communicating the composer’s intentions” (i.e. paying attention to and acting upon directions in the score such as dynamics, tempo and expression markings, articulation, rests and pauses etc) or “conveying the story of the music“, but fundamentally I think as listeners we crave a performance which touches us personally. Listening to music is a highly subjective and personal experience – we’ve all had those ‘Proustian rush’ moments when a piece of music, or a single movement or even a phrase, provokes an involuntary memory, sometimes with physical side-effects such as goosebumps or shivers (physiologically, this is the result of the release of Dopamine, the brain’s “reward” neurotransmitter). Sometimes we want to feel uplifted or transported by music, taken us out of ourselves and the mundanity of everyday life to another place, to experience something touching the spiritual or transcendent. Such moments, and the memory of them, are very special and individual.

Occasionally one is at a concert where a very palpable sense of collective concentration can be felt in the auditorium. This occurs when the performer creates an intense communication between music and listener. I experienced it, along with the rest of the Wigmore Hall audience, at a performance of Beethoven’s last three sonatas by the Russian pianist Igor Levit in June 2017. The sense of concentrated listening and suspense was extraordinary. How did Levit achieve it? I’m not sure…. a combination of exquisite tone control, musical understanding and the sheer power of the music itself.

Most people like music because it gives them certain emotions such as joy, grief, sadness, and image of nature, a subject for daydreams or – still better – oblivion from “everyday life”. They want a drug – dope -…. Music would not be worth much if it were reduced to such an end. When people have learned to love music for itself, when they listen with other ears, their enjoyment will be of a far higher and more potent order, and they will be able to judge it on a higher plane and realise its intrinsic value.

– Igor Stravinsky

Dining With Music

by Maureen Buja, Interlude

Whim W’Him Contemporary Dance company in La revue du cuisine (2015)

As you peek around the corners of the repertoire, there are a few pieces that reflect the daily concern with Dining. There are works that set recipes, works that show the activities in a kitchen, works that show the procession of the courses, and one that gives you the ambient sound of a large kitchen. Let’s explore!

Martinů’s La revue de cuisine (1927) was still a favourite of its composer some 50 years later. It was a one-act jazz ballet about a love triangle in the kitchen between Pot, Lid, and the adventurous Whisk to which Pot has become enamoured. ‘The forthcoming marriage between Pot (Le chaudron) and Lid (Le couvercle) is jeopardised by the adventurous Whisk (Le moulinet) to whose magic Pot has succumbed. Pot is so captivated that Lid falls off him and rolls into a corner of the kitchen. Now Dishcloth wants to seduce Lid but order loving Broom to challenge Dishcloth to a duel, which delights Whisk. The two irritated combatants fight to the bitter end. Whisk makes eyes at Pot once more but now Pot longs for Lid, but Lid is nowhere to be found. The shadow of an enormous foot appears suddenly and with one kick propels Lid out of his corner. Broom leads him back to Pot, while Whisk and Dishcloth break out into a wild dance of joy.’ Despite this wildly interesting synopsis, the work has rarely been performed as a ballet in its entirety but has had a much more successful life as a suite. One recent version in 2013 moved the scenario to that of a traveling circus. The ballet score was revised and reconstructed by Christopher Hogwood after the full score was found in the Paul Sacher Foundation Archives.

Darius and Madeleine Milhaud on their wedding day, 1925

French composer Darius Milhaud (1895-1974) left France in 1940 when the Germans invaded and took up a post at Mills College in California. One of the changes that the Milhaud family experienced in America was the lack of household help. Cooks and maids were no longer available in war-time America. Milhaud paid tribute to his wife in 1944 in La Muse ménagère (The Household Muse), which recognizes his wife Madeleine’s ingenuity in having to take up household tasks during their time in the United States, where, as Milhaud noted, ‘servants receive higher wages than university professors.’ Her whirlwind kitchen activities are covered in the movement entitled La cuisine.

Jennie Tourel and Leonard Bernstein at a recording session, 1960

A ‘song cycle of recipes’ takes Emile Dumont’s 1899 cookbook La Bonne Cuisine Française (Tout ce qui a rapport à la table, manuel-guide pour la ville et la campagne) (Fine French Cooking “Everything That Has to Do with the Table, Manual Guide for City and Country”) as the text source for Leonard Bernstein’s 1947 work. Written for singer Jennie Tourel, it sets the recipes for Plum Pudding, Ox Tail, a Turkish dish of Tavouk Guenksis, and closes with a recipe for ‘Rabbit at Top Speed.’

Kitchen in Chateau d’Orion

In his 1961 work Grand Concerto Gastronomique for Eater, Waiter, Food and Large Orchestra, Op. 76, English composer Malcolm Arnold wrote a 6-part memorial to a great dinner. Written for the Hoffnung Festival in 1961, the work involved the actions of an off-stage chef and two on-stage actors (the Eater and the Waiter). The Prologue, with its fanfares and ‘comic gestures’ signals the beginning of the action: the Eater and the Waiter enact a ‘ceremonial napkin display’ and the meal is on. The second movement, Soup (Brown Windsor), is both ‘thickly scored and unappealing’, rather like the soup. It is in the third movement, Roast Beef, that the Englishness comes out. The movement may be short, but the performance instructions say that it must be ‘repeated and repeated slower and slower until all is finished’ and the plate of food must be ‘enormous.’ It is the Eater who determines how many repetitions of the march occur – choosing either to gulp everything down as quickly as possible or to savour every morsel, in the manner of Erik Satie’s piano piece Vexations (which 1 page of music is to be played 840 times).

This movement is followed by Cheese, and then the dessert course of Peach Melba and closes with Coffee, Brandy, Epilogue.

English composer Gavin Bryars’ work Cuisine (1993) was written for an installation at Chateau d’Orion, in Orion, France. The music was written to establish the ‘architectural acoustic’ of the space and ‘to animate the spaces in which the music was played.’

We all have our triumphs and failures in the kitchen. Each of these composers has chosen to memorialize something different for their kitchens: love affairs between the implements, the musicality of a recipe, the ceremony of a meal, or just the sound of the space.

Thinking About Returning to the Piano?

by Frances Wilson, Interlude

It may be two years or twenty since you last touched a piano, but however long the absence, taking the decision to return to playing is exciting, challenging and just a little trepidatious.

Stick with the familiar and play the music you learnt before

Stick with the familiar and play the music you learnt before

To get back in to the habit of playing, start by returning to music you have previously learnt. You may be surprised at how much remains in the fingers and brain, and while facility, nimbleness and technique may be rusty, it shouldn’t take too long to find the music flowing again, especially if you learnt and practised it carefully in the past.

Take time to warm up

You may like to play scales or exercises to warm up, but simple yoga or Pilates-style exercises, done away from the piano, can be very helpful in warming up fingers and arms and getting the blood flowing. This kind of warm up can also be a useful head-clearing exercise to help you focus when you go to the piano.

You don’t have to play scales or exercises!

Some people swear by scales, arpeggios and technical exercises while others run a mile from them. As a returner, you are under no obligation to play scales or exercises. While they may be helpful in improving finger dexterity and velocity, many exercises can be tedious and repetitive. Instead try and create exercises from the music you are playing – it will be far more useful and, importantly, relevant.

Invest in a decent instrument

If you are serious about returning to the piano, a good instrument is essential. It needn’t be an acoustic piano; there are many very high-quality digital instruments to choose from. Select one with a full-size keyboard and properly weighted keys which imitate the action of a real piano. The benefits of a digital instrument are that you can adjust the volume and play with headphones so as not to disturb other members of your household or neighbours, and most digital instruments allow you to record yourself or connect to apps which provide accompaniments or a rhythm section which makes playing even more fun!

Posture is important

You’ve got a good instrument, now invest in a proper adjustable piano stool or bench. Good posture enables you to play better, avoid tiredness and injury.

Little and often

Your new-found enthusiasm for the piano may lead you to play for hours on end over the weekend but hardly at all during the week. Instead of a long practice session, aim for shorter periods at the piano, every day if possible, or at least 5 days out of 7. Routine and regularity of practice are important for progress.

Consider taking lessons

A teacher can be a valuable support, offering advice on technique, productive practising, repertoire, performance practice, and more. Choose carefully: the pupil-teacher relationship is a very special one and a good relationship will foster progress and musical development. Ask for recommendations from other people and take some trial lessons to find the right teacher for you.

Pianists at Finchcocks course

Go on a piano course

Piano courses are a great way to meet other like-minded people – and you’ll be surprised how many returners there are out there! Courses also offer the opportunity to study with different teachers, hear other people playing, get tips on practising, chat to other pianists, and discover repertoire. Many courses in the UK cater for students of all levels, including those at Finchcocks in Kent and Jackdaws in Somerset.

Join a piano club

If you fancy improving your performance skills in a supportive friendly environment, consider joining a piano club. You’ll meet other adult pianists, hear lots of different repertoire, have an opportunity to exchange ideas, and enjoy a social life connected to the piano. Piano clubs offer regular performance opportunities which can help build confidence and fluency in your playing.

Listen widely

Listening, both to CDs or via streaming or going to live concerts, is a great way to discover new repertoire or be inspired by hearing the music you’re learning played by master musicians.

Buy good-quality scores

Cheap, flimsy scores don’t last long and are often littered with editorial inconsistencies. If you’re serious about your music, invest in decent sheet music and where possible buy Urtext scores (e.g. Henle, Barenreiter or Weiner editions) which have useful commentaries, annotations, fingering suggestions and clear typesetting on good-quality paper.

Play the music you want to play

One of the most satisfying aspects of being an adult pianist is that you can choose what repertoire to play. Don’t let people tell you to play certain repertoire because “it’s good for you”! If you don’t enjoy the music, you won’t want to practice. As pianists we are spoilt for choice and there really is music out there to suit every taste.

Above all, enjoy the piano!