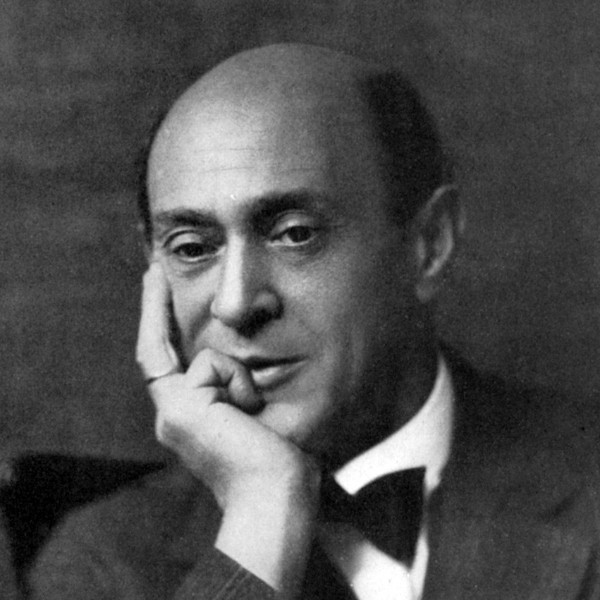

August Prinzhofer: Hector Berlioz, 1845

Berlioz’s music is dramatic, colourful, and intensely expressive, often telling stories or painting emotions so vividly they seem to leap off the page. What makes him truly fascinating is the way literature fuelled his imagination.

Writers like Goethe, Shakespeare, and Byron weren’t just influences; they were companions on his artistic journey, inspiring him to explore new forms of musical storytelling and to transform emotion into sound.

To celebrate his birthday on 11 December 1803, let’s explore how these three literary giants shaped his work, and why Berlioz’s music continues to captivate audiences nearly two centuries later.

When Words Inspired Music

Hector Berlioz

Berlioz grew up during a time when Romanticism was changing the way people thought about art, literature, and music. Romanticism celebrated emotion, imagination, individuality, and the dramatic aspects of life and nature. For Berlioz, literature wasn’t just something to read; it was the spark for musical ideas.

He devoured works from German, English, and French authors, letting their stories, characters, and emotions seep into his mind. In his music, he didn’t just set words to notes but translated the spirit of literature into sound.

Three writers stand out as especially important. Johann Wolfgang von Goethe, William Shakespeare, and Lord Byron each offered something unique. Goethe provided psychological insight, Shakespeare inspired dramatic spectacle, and Byron fuelled passionate intensity. These authors helped to shape Berlioz’s bold and innovative musical voice.

Goethe’s Psychology

Joseph Karl Stieler: Johann Wolfgang von Goethe at age 79, 1828 (Neue Pinakothek)

Johann Wolfgang von Goethe (1749–1832) fascinated Berlioz with his exploration of human emotion and inner conflict. Goethe’s works often delve into moral dilemmas, personal struggles, and the tension between desire and duty, topics that Berlioz found irresistible.

He was captivated by Goethe’s Faust, with its intense psychological depth and exploration of temptation, ambition, and redemption. In his dramatic legend La Damnation de Faust, the orchestra becomes an extension of Faust’s inner world.

From the brooding tension of Faust’s introspective moment to the fiery intensity of his devilish encounters, the music mirrors the constant struggle between desire and conscience. Melodic motifs reappear throughout the work as Berlioz transforms Goethe’s complex psychological landscape into a living and breathing musical experience.

Just as Goethe blended narrative, reflection, and dialogue in his plays, Berlioz created music where instruments, voices, and motifs interact like characters in a drama. His attention to detail, mood, and pacing reflects Goethe’s meticulous craftsmanship, proving that literature and music can be deeply intertwined.

Shakespearean Drama

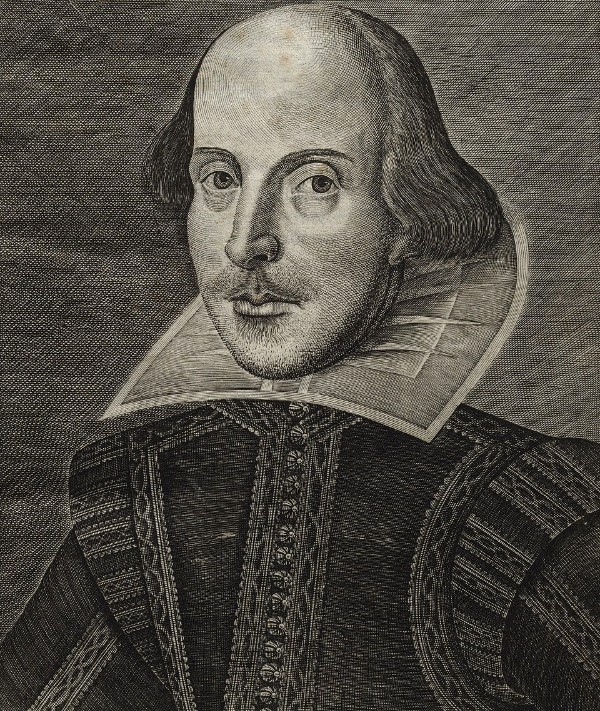

William Shakespeare

If Goethe shaped Berlioz’s inner emotional world, William Shakespeare (1564–1616) inspired his sense of drama and theatricality. Shakespeare’s plays are full of vivid characters, intense emotion, and unexpected twists, all qualities Berlioz sought to bring into music.

Berlioz’s opera Béatrice et Bénédict (1862), based on Much Ado About Nothing, puts the feisty, witty Béatrice and the clever Bénédict at its centre, showing how Shakespeare’s sharp characterisation and playful tension could be transformed into musical drama. Berlioz captures the characters’ personalities, their banter, and the slow-burning romance between them, turning Shakespeare’s comic brilliance into a vivid operatic experience.

In this opera, Berlioz also applies the pacing and tension of Shakespearean drama, making each scene feel like a self-contained story within the larger narrative. The characters are not simply singing; they are living, breathing, and reacting with all the emotional nuance Shakespeare endowed them with.

And just as Shakespeare occasionally introduced supernatural or fantastical elements into his plays, Berlioz infused his music with a sense of imagination and theatricality. In Béatrice et Bénédict, it is Shakespeare’s combination of clever wit, lively romance, and human depth that Berlioz channels to create an opera that feels both intimate and theatrically engaging.

Byron’s Passion

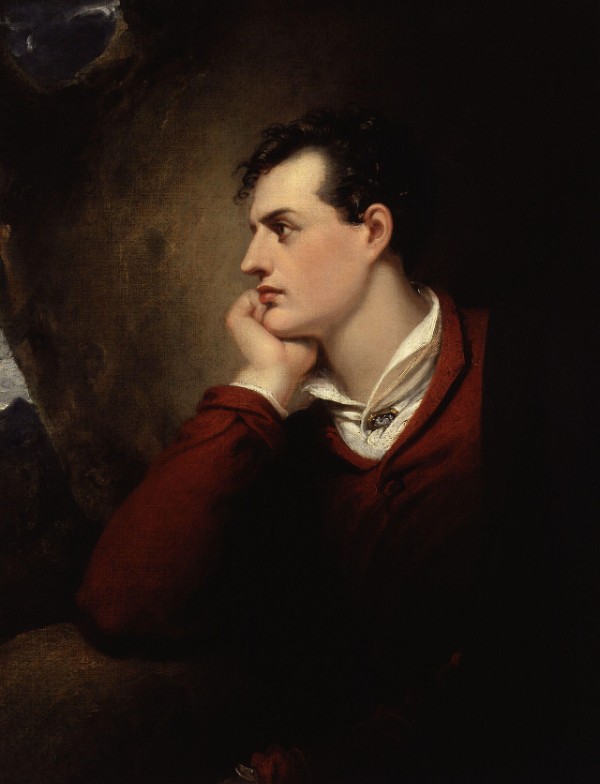

Lord Byron

Lord Byron (1788–1824) added another layer to Berlioz’s artistic vision. Byron’s poetry was full of intense emotion, larger-than-life heroes, and struggles against fate or society. Berlioz, who was drawn to extreme emotions and dramatic narratives, found in Byron a perfect literary model.

Berlioz was particularly inspired by Byron’s Childe Harold’s Pilgrimage and Manfred. The brooding, tormented heroes in these works mirror the intensity found in Berlioz’s music.

The protagonist’s inner turmoil, moral struggles, and encounters with supernatural forces echo the Byronic hero’s emotional and existential battles.

Byron encouraged Berlioz to embrace boldness, not just in story but in music itself. The sweeping melodies, dramatic dynamics, and daring orchestration in Berlioz’s works can be seen as musical equivalents of Byron’s passionate poetry.

Orchestra as Storyteller

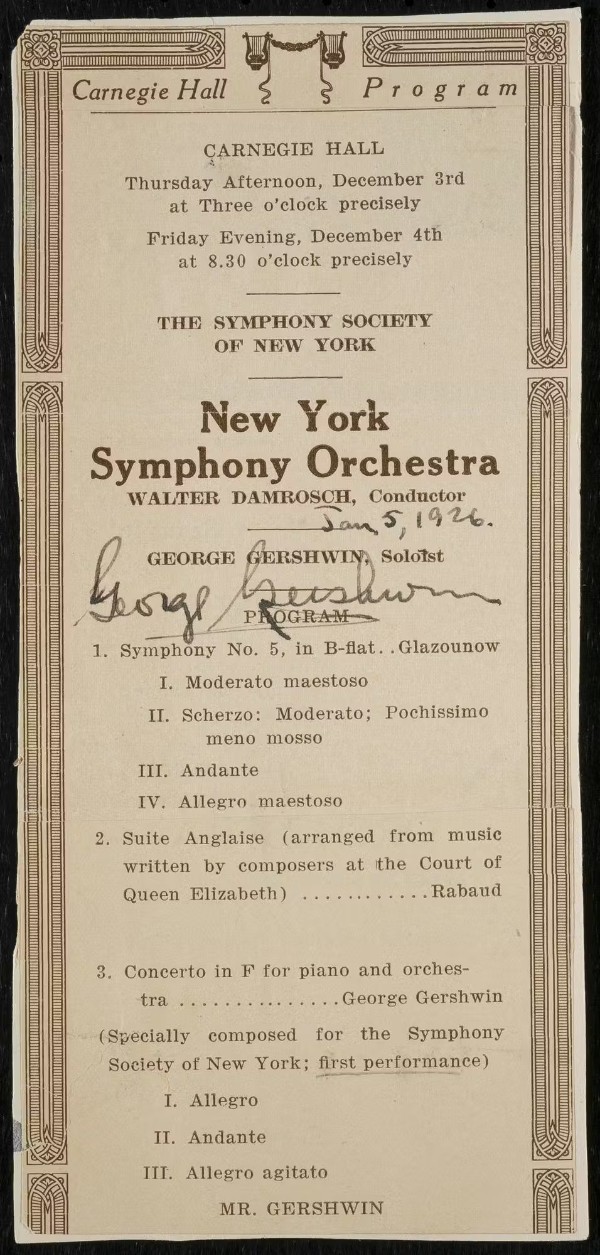

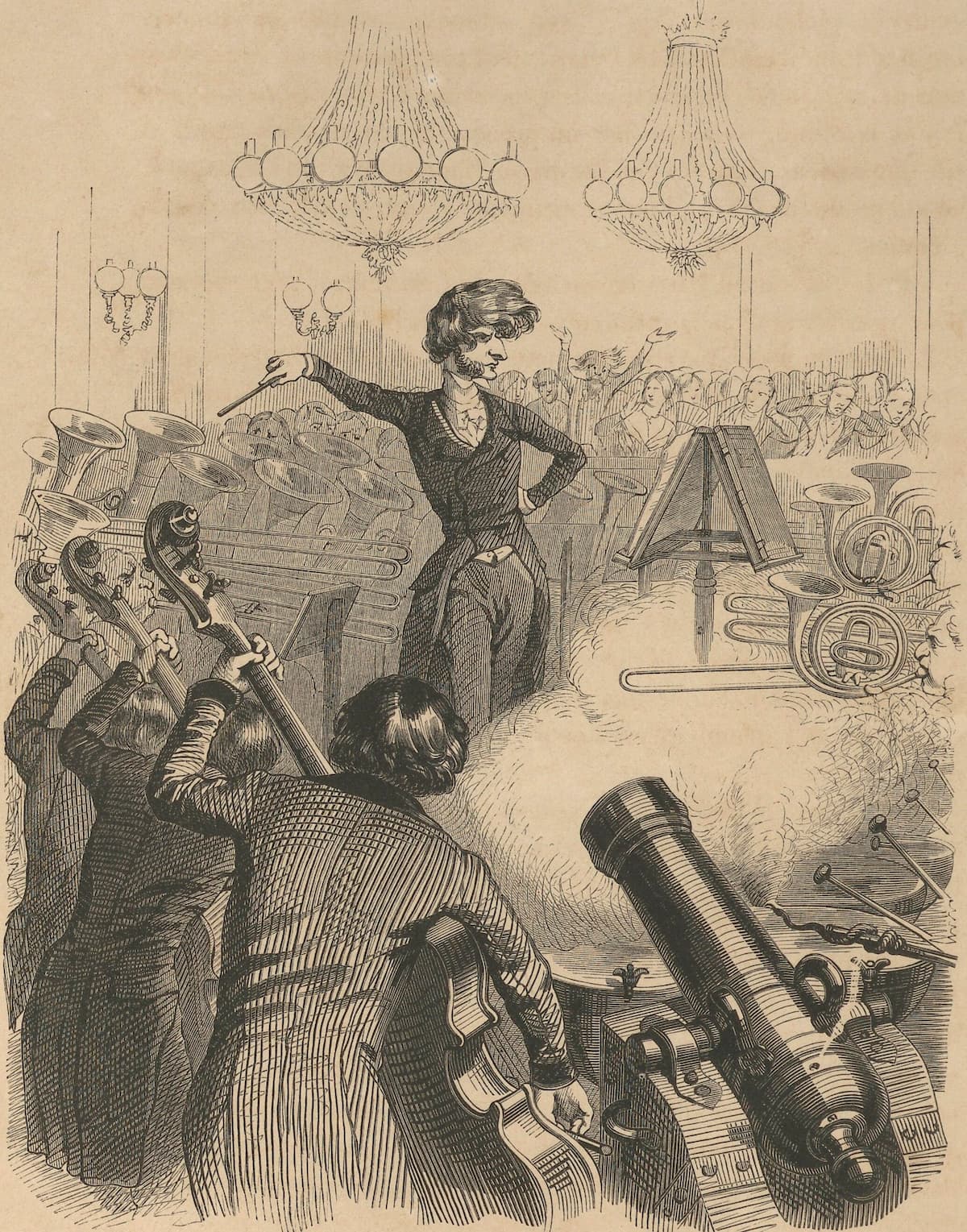

Caricature of Hector Berlioz conducting the orchestra

What makes Berlioz extraordinary is how he translated these literary influences into music. He didn’t simply set texts to notes; he absorbed the ideas and emotions from literature and expressed them through orchestration, harmony, and form.

The idée fixe, the recurring musical theme representing the beloved in the Symphonie fantastique, acts like a literary motif, threading through the narrative and expressing obsession, longing, and despair.

The music tells a story in a way only Berlioz could speak. In his operas and choral works, the orchestra itself becomes a storyteller, painting scenes and moods with remarkable clarity.

Berlioz’s engagement with literature also allowed him to challenge traditional musical structures. Rather than strictly following classical symphonic forms, he let the narrative and emotion dictate the music’s shape, creating works that feel organic, dynamic, and profoundly human.

Crossing Disciplines

Berlioz’s deep literary connections helped redefine what music could do. He showed that orchestral and operatic works could not only entertain but also convey complex psychology, moral dilemmas, and vivid drama.

Later composers, from Wagner to Mahler, would build on this idea, but Berlioz was among the first to fully realise it in the Romantic era.

His example also demonstrates the power of artistic cross-pollination. Literature and music are often taught as separate disciplines, but for Berlioz, they were inseparable.

By translating the spirit of Goethe, Shakespeare, and Byron into sound, he created music that is intellectually stimulating, emotionally compelling, and endlessly imaginative.

Literature, Passion, and Musical Brilliance

As we approach Hector Berlioz’s birthday on December 11, it’s a perfect time to celebrate not only his genius but the literary forces that inspired it. Goethe offered insight into the human heart, Shakespeare brought drama and theatricality, and Byron fuelled passion and Romantic heroism.

Berlioz took these influences and transformed them into a musical language that speaks directly to our emotions, telling stories with a vividness that few composers have matched.

Nearly two centuries later, his music still surprises, excites, and moves audiences around the world. It is a testament to the power of literature, imagination, and the unique genius of a man who could hear the poetry of words and turn it into unforgettable sound.