by

Over the centuries, classical composers have used their fame and fortune to support various philanthropic causes.

Whether raising funds for wounded soldiers, supporting abandoned children, or helping fellow musicians in need, all of these composers felt compelled to give back to society after their musical successes…and it’s fascinating to know what causes were closest to their hearts.

Here are eight composers and the causes they supported.

George Frideric Handel and the Foundling Hospital

Portrait of George Frideric Handel by Thomas Hudson, 1756

The Foundling Hospital was founded in 1739 for the “education and maintenance of exposed and deserted young children.”

As its name suggests, the institution focused on improving child health, but it also provided housing and basic clothing. At fourteen, boys were apprenticed into a trade; at sixteen, girls were apprenticed as servants. It was a grim future, but certainly better than the alternatives!

The Foundling Hospital became a popular cause for wealthy and artistic types to support. Supporters include William Hogarth, Sir Joshua Reynolds, Thomas Gainsborough, and others.

In May 1749, Handel conducted a benefit concert for the Foundling Hospital. He wrote a special work for the occasion, the “Foundling Hospital Anthem.” At the end, Handel tacked on his Hallelujah Chorus, before that work had become famous.

The following year, Handel donated a pipe organ to the hospital chapel and gave two more benefit concerts there.

In fact, an annual performance of Messiah began to be held at the hospital, which helped grant that work its place in the musical canon.

Handel’s concerts raised around £7000 (the rough equivalent of £1 million plus today).

Ludwig van Beethoven and Wounded Austrian Soldiers

Christian Honeman: Ludwig van Beethoven, 1803 (Beethovenhaus Bonn)

The Battle of Hanau occurred between Austro-Bavarian forces and French Napoleonic forces in late October 1813. The French won.

Five weeks later, in early December 1813, Ludwig van Beethoven participated in a fundraising concert in Vienna meant to benefit injured Austrian soldiers. The orchestra was made up of the stars of Viennese music, like Ignaz Schuppanzigh, Spohr, Hummel, Meyerbeer, and Salieri.

Beethoven’s remarks included the observation “We are moved by nothing but pure patriotism and the joyful sacrifice of our powers for those who have sacrificed so much for us.”

At this performance, he premiered his seventh symphony and his overture “Wellington’s Victory.” Both works were received enthusiastically by the audience

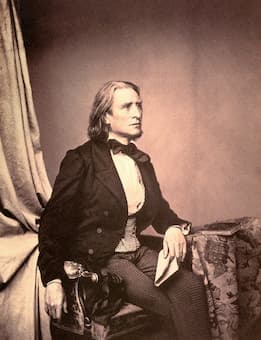

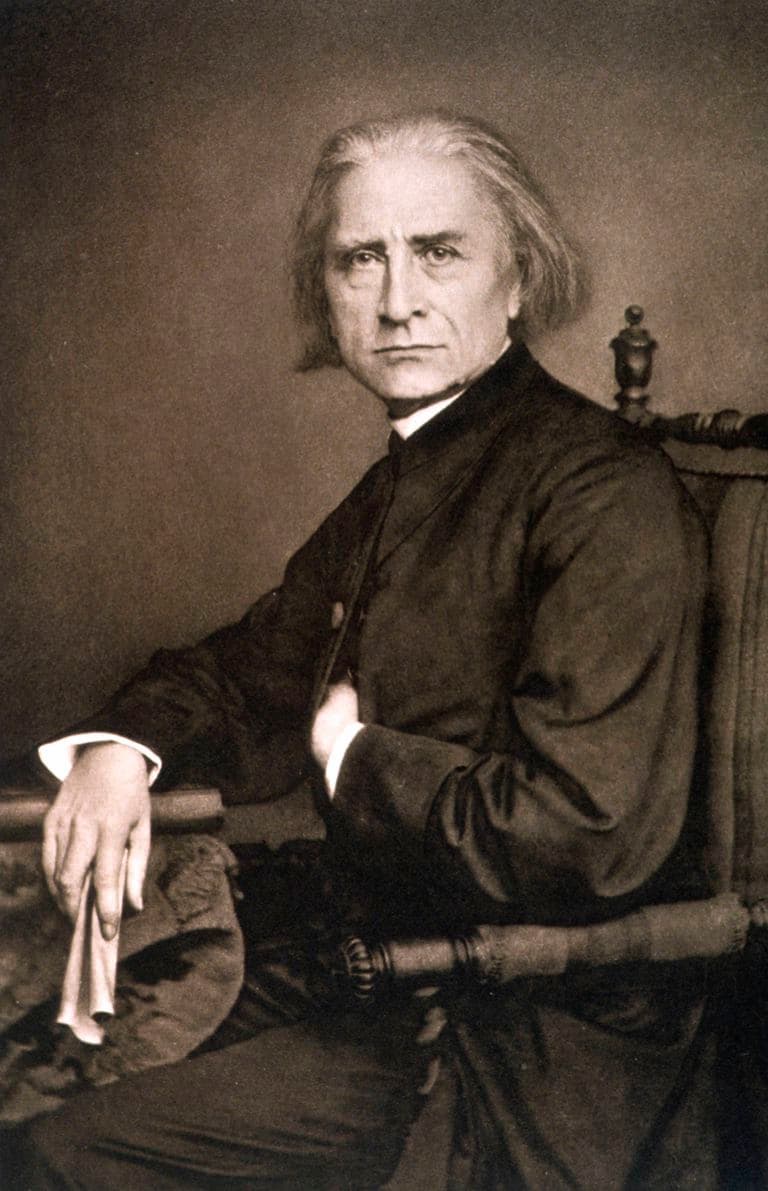

Franz Liszt for Flood Victims

Franz Liszt in 1870

In March 1838, a massive Danube River flood devastated towns and cities like Buda and Pest. The flood that year was especially severe due to melting ice and ice dams, and thousands lost their homes.

Although he was an international touring artist, Franz Liszt took his Hungarian roots extremely seriously. The next month, he took time out of his busy schedule to perform in Vienna to benefit the flood victims.

However, his partner Countess Marie d’Agoult was angry with him for his charity work. Their relationship was already fracturing, and she was frustrated that he left her to give (what she felt were) self-indulgent charity concerts. Liszt certainly didn’t assuage her concerns when he wrote letters to her on the stationery of wealthy society women who were helping with the fundraising!

Clara Schumann for Widowed Josephine Lang

Clara Schumann

Josephine Lang was a composer and pianist who was born in 1815. Robert and Clara Schumann befriended her; in fact, Robert Schumann published one of her songs in his magazine Neue Zeitschrift für Musik in 1838.

In 1842, Lang married a lawyer and poet named Christian Reinhold Köstlin. Their marriage was relatively short-lived, as he died tragically in 1856, leaving her an impoverished widow.

Josephine Lang

After struggling for a while, she reached out to Clara Schumann. She arranged a benefit concert for Lang and played in it for her friend.

Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky and Wounded Serbian Soldiers

Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky in 1893

In 1876, Russia supported Serbia in the Serbian-Ottoman War.

That summer, a music education organisation known as the Russian Music Society commissioned an orchestral work from Tchaikovsky. They wanted a work to be performed at a Red Cross fundraiser, with proceeds going to wounded Serbian soldiers.

He came back with his famous Marche Slav. The first section portrays the repression of the Serbs, and later sections depict the Russians coming to their aid.

The work has become incredibly popular over the ensuing years, but few know its philanthropic origins.

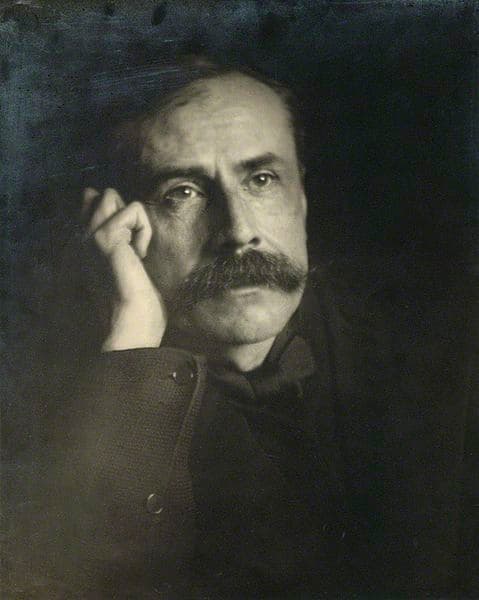

Edward Elgar for Belgian and Polish War Victims

Charles Frederick Grindrod: Edward Elgar, ca. 1903

World War I broke out in the summer of 1914. In August, Germany invaded neutral Belgium, to the horror of Britain.

Not long afterwards, Elgar wrote Carillon, a recitation of a patriotic poem by Belgian poet Émile Cammaerts to orchestral accompaniment. It premiered that December.

The next year, he wrote Polonia in honour of Poland. He included quotations from the Polish national anthem, patriotic songs, and themes by Polish musical heroes Chopin and Paderewski.

Elgar conducted the premiere of Polonia at the Polish Victims’ Relief Fund Concert in London in July 1915.

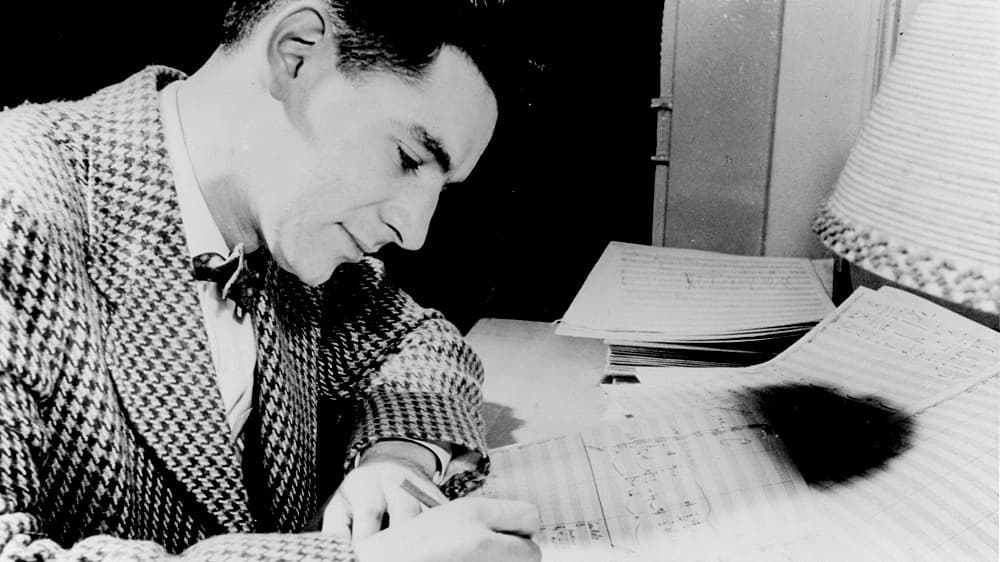

Leonard Bernstein for AIDS Activism

Leonard Bernstein

Composer and conductor Leonard Bernstein contributed to a number of charitable causes over his career, championing anti-war causes, Amnesty International, racial equity, and others.

One of the causes he helped fundraise for was AIDS activism, back when doing so was controversial due to the disease’s association with the gay community.

In 1986, he approached Mathilde Krim, the founding chairman of the American Foundation for AIDS Research, suggesting a fundraising concert.

In Krim’s words:

“And so it was that six short weeks later, on a cold December night, Aaron Neville and Linda Ronstadt sang ‘Ave Maria’ together, Isaac Stern played ‘Fiddler on the Roof;’ Bernadette Peters performed the First World War song ‘My Buddy,’ and Hildegard Behrens sang, ‘Falling in Love Again.’ The evening ended with a standing and swaying audience joining the performers singing ‘Somewhere’ from West Side Story. There wasn’t a dry eye in the house. It was another Lenny ‘miracle night,’ unforgettable for its intensity, beauty and depth of emotion. It also provided manna from heaven to several unfunded but most deserving AIDS research projects.”

This was at the beginning of the worst part of the AIDS crisis in America. Bernstein continued supporting the cause until his death in 1990.

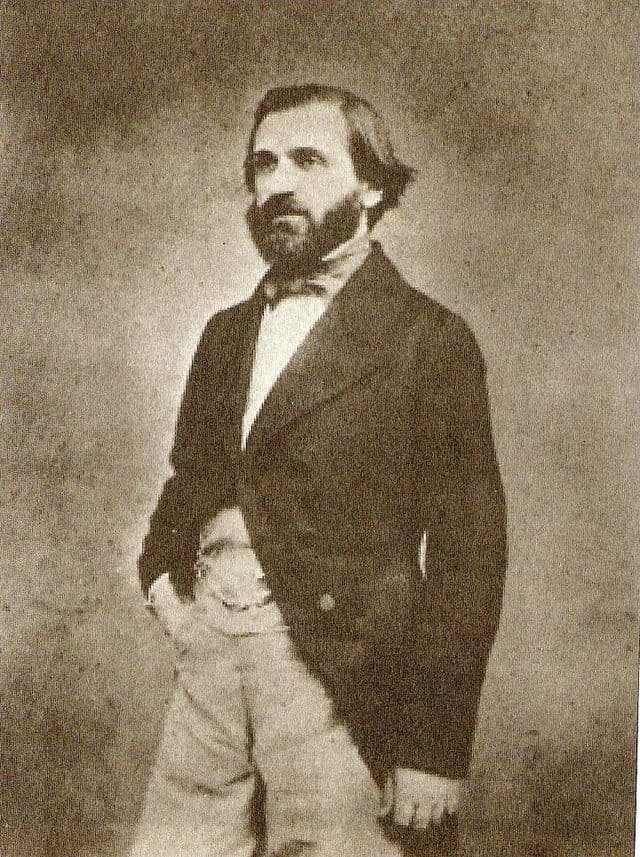

Giuseppe Verdi for Impoverished Elderly Musicians

Giuseppe Verdi, 1844

Thanks to his string of hugely successful operas, Giuseppe Verdi ended up becoming one of the wealthiest composers in the history of classical music. He wanted to give back.

In 1895, he planned and endowed a home for impoverished musicians in Milan, known as the Casa di Riposo per Musicisti (which became known as the Casa Verdi). He wrote that he wanted a safe place for “old singers not favoured by fortune, or who, when they were young, did not possess the virtue of saving.”

Verdi died in 1901. The following year, a handful of musicians moved into Casa Verdi.

Amazingly, the institution is still in existence today! According to a 2018 New York Times article:

The successful applicants get to spend their last years in a place where, in addition to room, board and medical treatment, they have access to concerts, music rooms, 15 pianos, a large organ, harps, drum sets and the company of their peers.