It's all about the classical music composers and their works from the last 400 years and much more about music. Hier erfahren Sie alles über die klassischen Komponisten und ihre Meisterwerke der letzten vierhundert Jahre und vieles mehr über Klassische Musik.

Total Pageviews

Monday, May 26, 2025

OPM legend Freddie Aguilar has died.

OPM legend Freddie Aguilar has died. He was 72.

He reportedly died at around 1:30 a.m. on May 27, 2025 at the Philippine Heart Center.

All reactions:

453You and 452 othersSunday, May 25, 2025

Jed Distler's Cliburn Blog No 3: New Voices and Familiar Faces

Jed Distler's Cliburn Blog No 3: New Voices and Familiar Faces

Jed Distler

Saturday, May 24, 2025

'Not one note fell under the table, not one phrase emerged without meaning'. Jed Distler finds at least one marvellous set in today's Cliburn Competition Preliminaries

Many Cliburn candidates have a history of shuttling from one competition to another. Not all of them rack up first prizes, but they gain considerable mileage along the way, making contacts and landing further opportunities for exposure. Some have a knack for cultivating a strong social media presence, or forging a so-called ‘brand’ for themselves. Indeed, quite a few of the 28 pianists we’ve heard during the Preliminaries have their own YouTube channels.

The American pianist Evren Ozel opened Friday’s events. I hadn’t heard him since he participated in the 2021 International Warsaw Chopin Competition, but he’s clearly evolved since then, as witness his ebullient Bach Partita No 5. Ozel played Rachtime very well, if not so arrestingly as others. In contrast to Mikhail Kambarov’s overwrought Rachmaninov Corelli Variations, Ozel proved a smooth and forthright operator. His was not a deep, soul searching rendition, yet the pianist’s unified tempo relationships and top-to-bottom clarity made their mark.

Watch Evren Ozel's performance:

Having won 2024’s Seoul International Music Competition, 28-year-old Sung Ho Yoo’s mature mastery came as no surprise. Yoo’s Haydn Andante and Variations in F minor, Hob.XVII:6, amounted to a masterclass in divining the right tempos, creating character and contrast, and not sweating the small stuff. I’m glad that Yoo chose Unsuk Chin’s inventive Etude No 2 (‘Sequenzen’) to showcase his considerable new-music affinity. Following a confident and colourful Rachtime, Rachmaninov’s Second Sonata (the 1931 revision) simply soared through Yoo’s cogent textural layering, impeccable transitions, gorgeous sonority and healthy exuberance. The word ‘generous’ kept coming to mind, as did memories of Van Cliburn’s similarly sane, big-boned live Moscow recording issued by RCA. Obviously that’s a compliment!

Sung Ho Yoo:

More world-class Rachmaninov was in store at the start of Chaeyoung Park’s marvellous set. What sexy chromatic passagework in the G major Prelude, Op 32 No 5. What pearly throughout the G sharp minor, Op 32 No 12. While Park read Rachtime from an iPad, her reading sounded memorised, deeply considered and patiently detailed, even if it didn’t pursue dynamic extremes. It takes a special pianist to sustain one’s undivided attention in Prokofiev’s long and often elusive Eighth Sonata, and Park is exactly that kind of artist. Not one note fell under the table, not one phrase emerged without meaning. Try to catch this performance as archived on The Cliburn’s YouTube channel, because its beauties are easier to hear than for me to describe, although I can attest to Park’s note-to-note continuity and ingenuous use of the pedal. Incidentally, if you’ve seen Park’s brilliant performance during the 2023 Arthur Rubinstein Competition’s second stage of Beethoven’s mighty ‘Hammerklavier’ Sonata, you’ll want to hear it again when she plays it next week, should she advance to the Semi-finals. Keep your fingers crossed.

Chaeyoung Park:

Spanish pianist Pedro López Salas came to my attention through the Keyboard Charitable Trust. Last year my colleague Christopher Axworthy praised Salas’s Mozart C major Sonata, K330, for its ‘subtle rubato and delectable ornaments’, and those words rang true today regarding the pianist’s opening salvo. Ginastera’s First Sonata seems to be Salas’s competition calling card; it prominently figured during the 12th International Paderewski Piano Competition, where the pianist garnered second prize. True to form, Salas brought stylish ‘swing’ to the first movement, and tossed of the second movement’s rapid unison lines with off-handed ease.

Pedro López Salas:

I liked 25-year-old Japanese pianist Kotaro Shigemori’s fluid ‘walking’ tempo for Chopin’s E major Nocturne, Op 62 No 2, plus the controlled passion and overall elegance of his Scriabin Sonata No 2. He had no trouble at all with Rachtime’s notes, yet he didn’t let the music breathe in the opening section. Conversely, in Liszt’s Dante Sonata the contrasts between stormy Hell and expansive Heaven came to life through his mindful virtuosity. Kotaro Shigemori was a new name for me, and I look forward to hearing more from him.

Kotaro Shigemori:

By contrast, I met Elia Cecino a few years ago when we both were performing at Cremona Mondomusica, and I attended his superb New York recital debut back in February 2024. So I was happy to see and hear him again in this context. He displayed ambidextrous agility in Shostakovich’s B flat major Prelude from Op 87, and razor-sharp point in the Fugue, which ever-so-slightly slowed down as it progressed (this happens in all live performances of this piece that I’ve heard, and is nothing to worry about!). With iPad at the ready, Cecino threw himself into Rachtime, where the piece took on a kinetic and fresh improvisatory dimension. It’s curious why one rarely hears Beethoven’s G major Sonata, Op 31 No 1, as a separate entity in recital, whereas one often hears its more popular D minor and E flat major companions. One reason may be its arguably overlong and difficult-to-sustain slow movement. Here, however, Cecino’s animated basic tempo and shapely right-hand cantabile phrasing consistently held my interest. His Gounod/Liszt Faust Waltz took off like a rocket, where tempo fluctuations and mood swings seemed less calculated and superimposed than organically generated, springing from a genuine musical impulse. Such daring Liszt playing is most welcome and sorely needed these days.

Elia Cecino:

Friday’s events concluded with two returnees from the 2022 Cliburn. I didn’t warm to Yangrui Cai back then, and I still find his accomplished and proficient pianism cold and charmless. His machine-like Fugue in the Bach D major Toccata, BWV912, seemed flat and machine-like next to Magdalene Ho’s living, breathing dance. The challenges throughout Carl Vine’s Five Bagatelles pose absolutely no problems for Cai’s finished technique, nor do the orchestral fireworks in the Wagner/Liszt Tannhäuser Overture transcription, where he banged his way through the final pages. He played Rachtime from memory, nailing down every note with the utmost assurance.

Yangrui Cai:

On the other hand, the Israeli/Russian Vitaly Starikov’s coloristic and expressive resources have blossomed since 2022. He coaxed beautiful and meaningful sounds from the piano in Bach’s F sharp minor Toccata, BWV910, and put a kinder, gentler face on Rachtime. One should ideally feel the outer sections of Chopin Fourth Scherzo in one long beat to a bar, and that’s how Starikov’s deliciously fleet and feathery performance transpired. The genial atmosphere Starikov had created thus far then changed on a dime with a terse and appropriately grim rendition of Shostakovich’s First Sonata.

Vitaly Starikov:

Perusing the list of 18 candidates who have progressed to the Quarter-finals, my impression is that the jury have mostly chosen well. However, I say ‘mostly’ because I am disappointed, enraged even, that Magdalene Ho didn’t make the cut. But then again, The Cliburn has a history of occasionally letting geniuses slip through the cracks. Remember 1977 and Youri Egorov? Nevertheless, I look forward greatly to the Quarter-finals, which start without a break. More tomorrow!

The 18 pianists who have progressed to the Quarter-finals are:

Piotr Alexewicz, Poland, age 25

Jonas Aumiller, Germany, 26

Alice Burla, Canada, 28

Yangrui Cai, China, 24

Elia Cecino, Italy, 23

Yanjun Chen, China, 23

Shangru Du, China, 27

Carter Johnson, Canada/United States, 28

Xiaofu Ju, China, 25

Mikhail Kambarov, Russia, 24

David Khrikuli, Georgia, 24

Philipp Lynov, Russia, 26

Jonathan Mamora, United States, 30

Evren Ozel, United States, 26

Chaeyoung Park, South Korea, 27

Aristo Sham, Hong Kong China, 29

Vitaly Starikov, Israel/Russia, 30

Angel Stanislav Wang, United States, 22

Gramophone is a Media Partner of The Cliburn International Piano Competition

Friday, May 23, 2025

Fast and Furious: Gounod’s Faust Ballets

by Maureen Buja

The story of Faust has captured composers’ imaginations for centuries. There was a historical figure, Johann Georg Faust (c. 1480–1540), who made the original deal with the devil at the crossroads when he exchanged his soul for unlimited knowledge and worldly pleasures. The idea of a ‘Faustian’ pact always carries with it the idea of sacrificing good (or the spiritual) for the evils of power, knowledge, and material gain. In preferring human knowledge over divine knowledge, Faust is damned from the beginning. From 16th-century puppet plays to Goethe’s tragic figure in the 19th century, Faust is always the symbol for ‘what if’ or ‘going to the dark side’.

The French composer Charles Gounod (1818–1893) met Faust in 1859. His opera, first given at the Théâtre Lyrique as an opéra comique, i.e., an opera with dialogue, in 1859, evolved over the next decade to have recitatives added (Strasbourg 1860), scenes removed (La Scala, 1862), and dances added (Paris Opéra, 1869). In working with Goethe’s text, Gounod slimmed down the number of characters and conflated them to better serve as opera. Opera moves more slowly than a play, so refining is always necessary.

Bayard & Bertall: Charles Gounod, 1860

The addition of ballet music was required for performance at the Paris Opéra. At first, Gounod didn’t want to write it and asked his student, Camille Saint-Saëns, to do it. Saint-Saëns, appalled at the request, went straight to Gounod to change his mind. Gounod finally agreed and created a score that more often had a life separate from the opera.

The ballet section was inserted into the first scene of the final act for the Paris Opéra performance, and that final addition made the former opéra comique a grand opera. It became the most frequently performed opera in Paris.

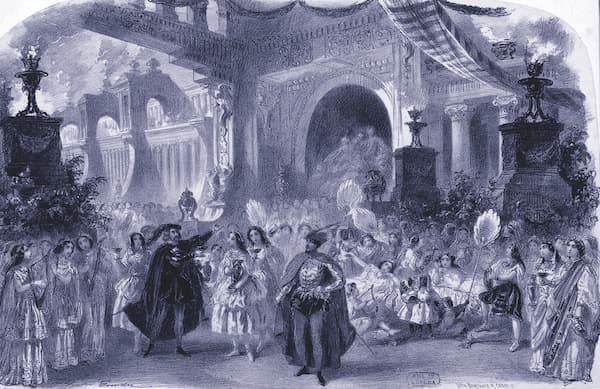

Charles-Antoine Cambon and Victor Coindre: The palace of Méphistophélès, Faust, 1859 (Paris: Bibliothéque national)

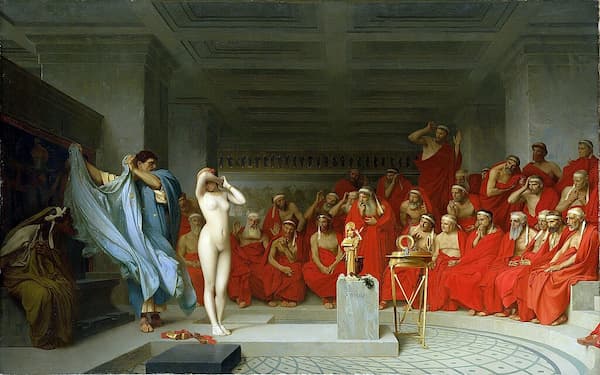

At the start of the last act, Méphistophélès and Faust are in the Harz Mountains on Walpurgis Night. An ‘orgiastic ballet’ becomes the focus for the revelry and concludes with Phrynes’s Dance. Phryne was an (in)famous Greek courtesan from the 4th century who was very wealthy. Put on trial for impiety, for profaning the Eleusinian Mysteries, she was acquitted when the jury saw her bare breasts.

Jean-Léon Gérôme: Phryne before the Areopagus, ca 1861 (Hamburger Kunsthalle)

Other dances in the ballet are by Nubian slaves, Cleopatra, and Trojan Women, all strong and well-known ideals of women that would appeal to Faust. It’s Phryne’s Dance that closes the ballet sequence.

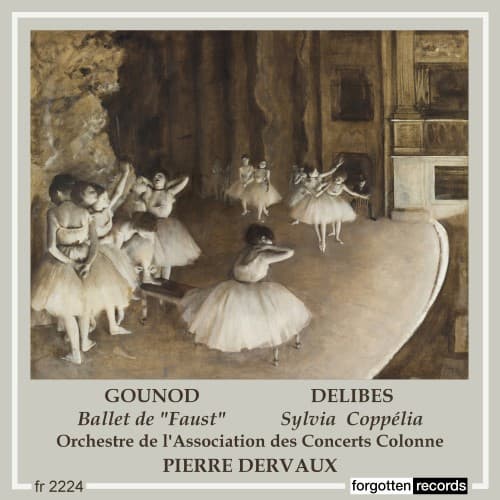

This 1958 recording was made by the Orchestre de l’Association des Concerts Colonne, led by Pierre Dervaux. The Colonne Orchestra was founded in 1873 by the violinist and conductor, Édouard Colonne. Colonne wanted an orchestra that could play contemporary music (Saint-Saëns, Massenet, Charpentier, Fauré, d’Indy, Debussy, Ravel, Widor, Enescu, Dukas, Chabrier, and the like), as well as the big German composers such as Wagner and Richard Strauss.

Pierre Dervaux

Pierre Dervaux (1917–1992) was President and Chief conductor of the Colonne orchestra from 1958 to 1992, starting his career as principal conductor of the Opéra-Comique (1947–53), and the Opéra de Paris (1956–72). He led many of France’s finest orchestras, including the Concerts Pasdeloup (1949–55) and was Musical Director of the Orchestre des Pays de Loire (1971–79) as well as holding similar posts at the Quebec Symphony Orchestra (1968–75), and the Nice Philharmonic (1979–82). He taught at the École Normale de Musique de Paris (1964–86) and the Conservatoire de musique du Québec à Montréal (1965–72).

Performed by

Pierre Dervaux

Orchestre de l’Association des Concerts Colonne

Recorded in 1958

Official Website

For more of the best in classical music, sign up for our E-Newsletter

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)