by Emily E. Hogstad, Interlude

So it’s no surprise that over the course of music history, quite a few conductors have died or suffered fatal injuries while on the podium.

Today, we’re looking at the stories of five conductors who did what they loved until the very end of their lives – and what music they were conducting when they passed away.

Jean-Baptiste Lully (1632-1687)

Portrait of Jean-Baptiste Lully by Paul Mignard

Lully was born in Tuscany in 1632. Historians don’t know a lot about his childhood, but it appears that he studied both music and dancing.

When he was in his early teens, he was plucked off the street by a chevalier who was searching for an Italian conversation partner for his niece, Anne Marie Louise d’Orléans, Duchess of Montpensier, who was heiress to one of the greatest fortunes in Europe.

This was his introduction to the French aristocracy. In 1653, he made a big impression while dancing with Louis XIV, the future Sun King. Within weeks, he was named royal composer for instrumental music.

In 1661, Lully was named superintendent of the royal music and music master of the royal family.

He fell into disfavor in the 1680s as rumors swirled surrounding his same-sex relationships. In 1685, he was accused of having an inappropriate relationship with a pageboy, and his home was raided by police. Although he never faced any legal consequences, the social and professional costs were steep, and Louis XIV distanced himself.

In 1687, Louis XIV underwent dental surgery. Things went sideways during the procedure, but somehow he survived. To celebrate the monarch’s unlikely recovery, Lully wrote a Te Deum.

During the performance, he used a staff to keep time and accidentally hit his foot with it. Gangrene set in, and Lully refused an amputation because didn’t want to give up his ability to dance. He died on 22 March 1687.

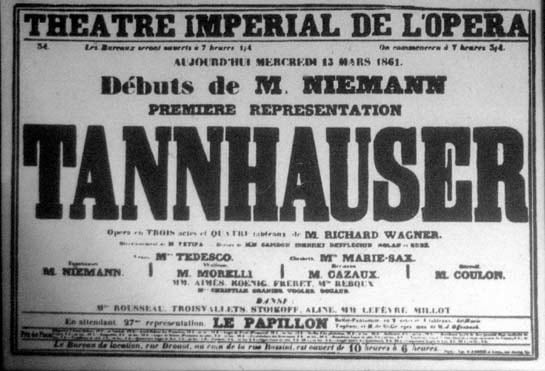

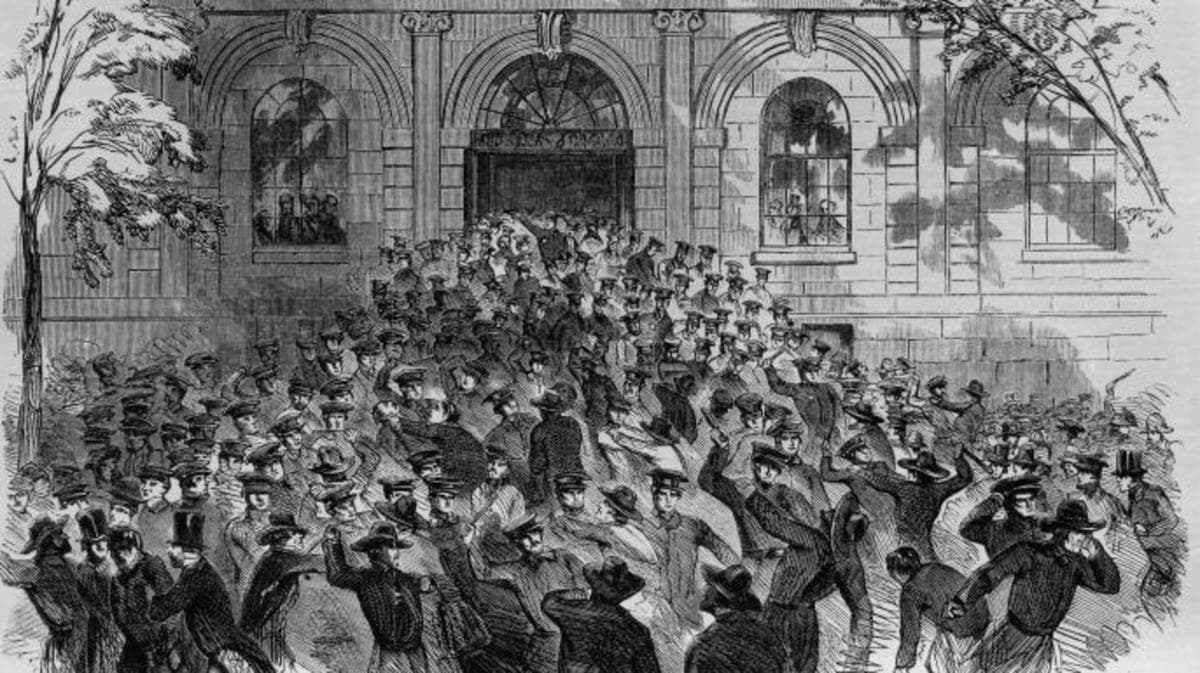

Narcisse Girard (1797-1860)

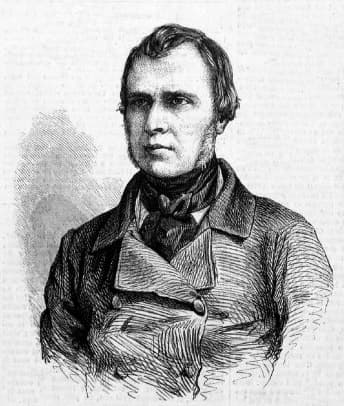

Narcisse Girard

Narcisse Girard was born in Nantes, France, and studied at the Paris Conservatoire with violinist Pierre Baillot and Beethoven‘s friend Anton Reicha.

As a young man, he scored prestigious positions at the Opéra Italien, Opéra Comique, and Paris Opéra in Paris.

He gave a series of important premieres, including Hector Berlioz’s work for viola and orchestra Harold en Italie in 1834; Giacomo Meyerbeer’s opera Le prophète in 1849; and Charles Gounod’s opera Sapho in 1851.

One of his career highlights was conducting a performance of the Mozart Requiem at Chopin’s memorial service.

In 1860, he fell ill and conducted a concert at the Conservatoire while sick. Next he took on a performance of Meyerbeer’s opera Les Huguenots, which clocks in at close to four hours. After the third act, Girard collapsed and later died.

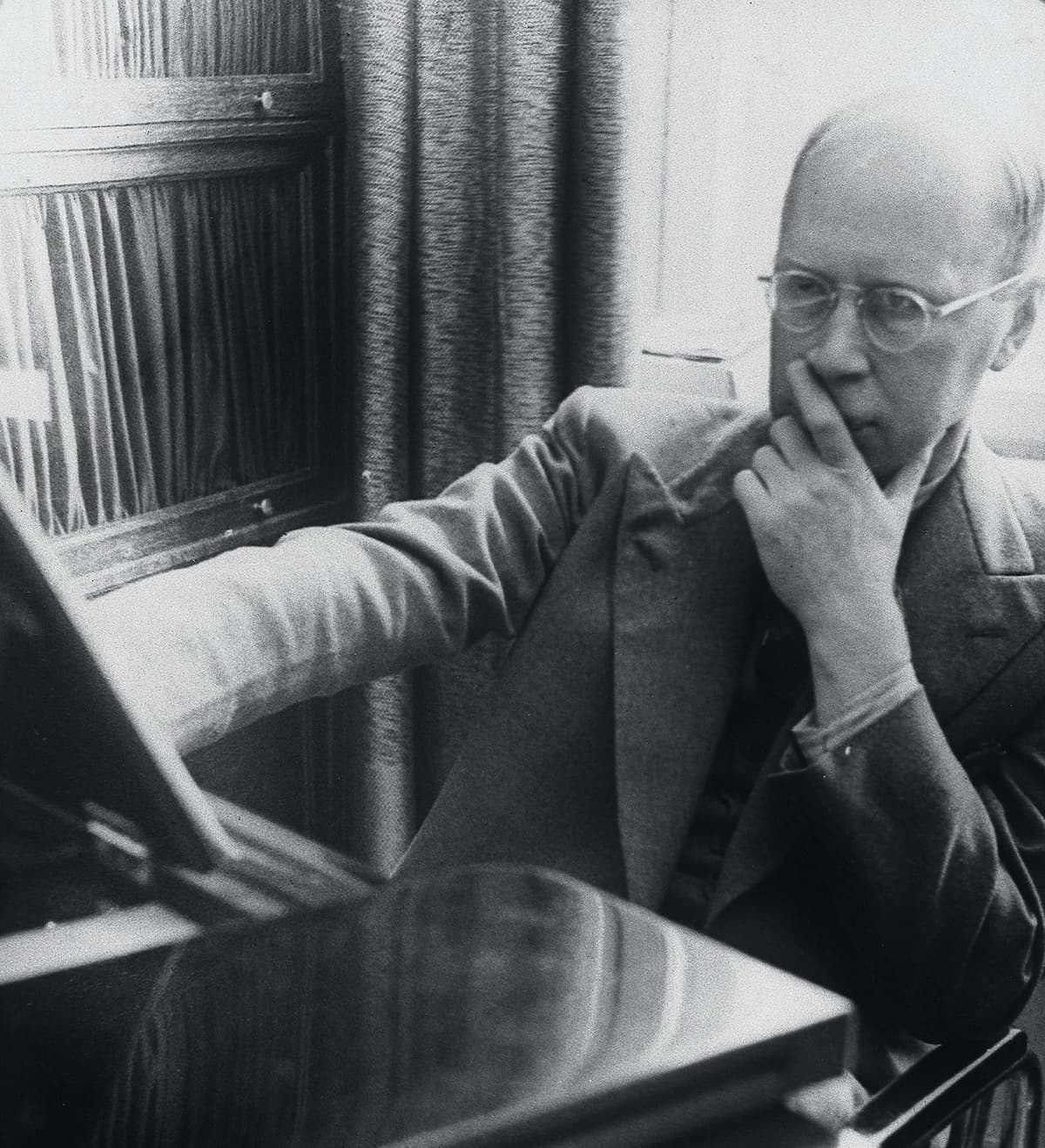

Dimitri Mitropoulos (1896-1960)

Dimitri Mitropoulos

Dimitri Mitropoulos was born in Athens in 1896. He studied at the Athens Conservatory before becoming an assistant conductor at the Berlin State Opera.

One memorable performance in Berlin in 1930 saw him play and conduct Prokofiev’s third piano concerto from the keyboard after the scheduled soloist had fallen ill.

He emigrated to the United States in 1936 and conducted orchestras in Boston and Minneapolis before becoming the music director of the New York Philharmonic in 1951.

His young, dynamic student Leonard Bernstein succeeded him in 1957. Mitropoulos’s gentle persona, inability to enforce strict discipline with his players, bad press, and rumored homosexuality all combined to end his music directorship at the Philharmonic.

He spent the rest of his career specializing in opera. He gave many performances at the Metropolitan Opera.

In November 1960, Mitropoulos was rehearsing Mahler’s massive third symphony at La Scala Opera House in Milan. According to press reports, he stopped, mumbled that he was feeling sick, and collapsed. The musicians immediately stopped playing and tried to assist him, but it was no use; he had suffered a massive cerebral haemorrhage. He died on his way to a Milanese hospital.

Eduard van Beinum (1900-1959)

Eduard van Beinum

Eduard van Beinum was born in 1900 in the city of Arnhem in the Netherlands. He studied violin, viola, and piano as a child, and when he was eighteen, joined the Arnhem Orchestra. Later he attended the Amsterdam Conservatory.

In 1929, he conducted the Concertgebouw Orchestra for the first time. Two years later, he was named second conductor, under the esteemed – and autocratic – Willem Mengelberg.

During the Nazi invasion, the two men found themselves caught up in politics.

Mengelberg flirted with Nazism, being photographed with Nazi officials and once telling an interviewer he drank champagne when the Netherlands surrendered to Nazi forces. His words and actions eventually forced him into postwar exile in Switzerland.

Meanwhile, the genial van Beinum refused to conduct a Nazi benefit concert in 1943 and threatened to resign from his position if he was compelled to play the event.

Eduard van Beinum Conducts Beethoven’s Symphony No. 3 Op.55

After Mengelberg was pushed out in 1945, van Beinum stepped up to become the ensemble’s music director. He also served at various times as music director of the London Philharmonic and the Los Angeles Philharmonic.

On 13 April 1959, van Beinum was at the Concertgebouw rehearsing Brahms’s first symphony when he had a heart attack and died.

Fritz Lehmann (1904-1956)

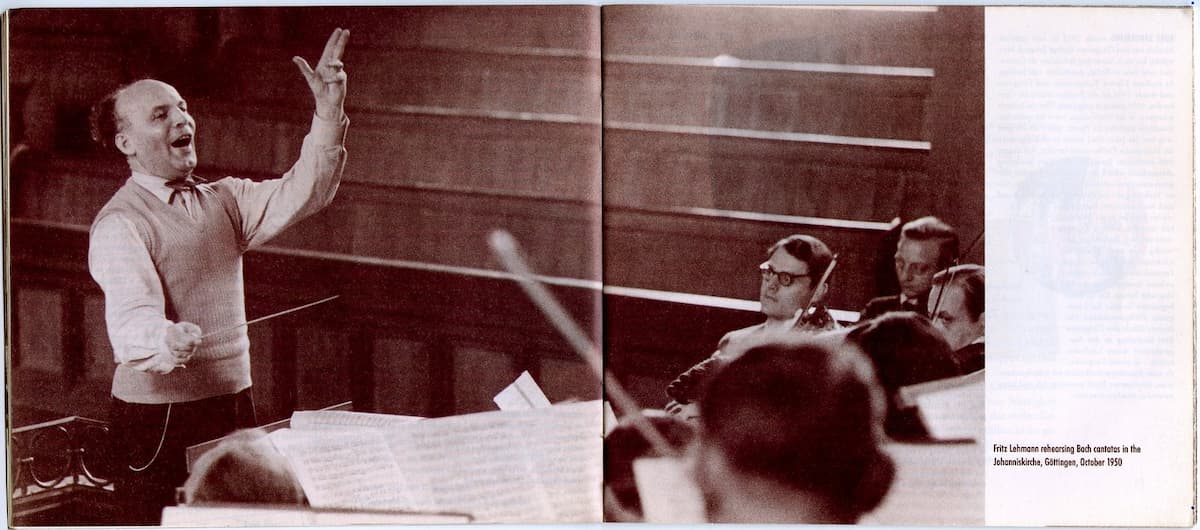

Fritz Lehmann

Fritz Lehmann was born into a musical family in Mannheim, Germany, in 1904. As a teenager, he studied at the Hochschule für Musik in Mannheim, eventually transferring to universities in Heidelberg and Göttingen.

He made a career conducting various German orchestras, and in 1934, he was hired as the conductor of the Göttingen International Handel Festival. Ten years later, he resigned when, like van Beinum, he came in conflict with Nazi officials.

One of his specialties was Johann Sebastian Bach. On Good Friday in 1956, he conducted a particularly fateful performance of the St. Matthew Passion in Munich.

During the performance, he had a heart attack and collapsed. A replacement conductor came out to finish the work. After the Passion was finished, it was announced that Lehmann had not survived.