By Sophia Alexandra Hall, ClassicFM

Army of Thieves is the prequel to the Netflix zombie movie, Army of the Dead, and the film takes a surprising amount of inspiration from Richard Wagner’s Ring Cycle.

German composer Richard Wagner is trending, and it might not be for the reason you think.

Netflix’s latest heist movie, Army of Thieves, tells the story of a German safe-cracker, Dieter, who is hired by an internationally renowned heist team to break into a series of safes inspired by Wagner’s Der Ring des Nibelungen (Ring Cycle).

The film is a prequel to the zombie movie released on the streaming platform earlier this year, Army of the Dead, which also stars German actor Matthias Schweighöfer as Dieter, and is directed by Zach Snyder.

Every good heist movie has *that* scene, where the characters tensely wait as the skilled member of their team attempts to open a vault full of goods. One false move, and it could mean the end of their entire mission, and possibly prison time or death for the whole team.

Well if you enjoy those kind of scenes, get ready for at least three in this film alone, and that’s not including the underground safe-cracking ring which Dieter finds himself in for a series of games in front of a betting audience.

Bank-teller Sebastian Schlencht-Wöhnert (aka. Dieter), is an expert in all things safe-cracking. At the beginning of the film, we see him sharing his knowledge to his 0 subscriber YouTube channel, where he makes videos about his favourite safe-maker, Hans Wagner.

In the film, Hans Wagner is introduced as a German master-locksmith, who is famed with having created four almost impenetrable safes based on Richard Wagner’s Ring Cycle.

Dieter is therefore recruited by an international heist gang to assist in their plan to break into three of these four safes, after one of the members sees his YouTube video on the safes. By joining the team, he begins a character transition from Sebastian Schlencht-Wöhnert the bank-teller, into Ludwig Dieter, the international safe-cracker.

The parallels between this story and Wagner’s Ring Cycle become obvious as the film plays out. As Dieter cracks each of the three safes in Hans Wagner’s own Ring Cycle, he plays famed music from the opera, while explaining to his team member, Gwendolyn, a brief summary of the musical work and significance.

Here’s a brief introduction to the four operas which comprise Wagner’s Ring Cycle, and how they are linked to the safes in Army of Thieves.

Das Rheingold (The Rhinegold)

Wagner’s first opera of the Ring Cycle was completed in 1854. Despite being the first score to be completed, it was actually the last text to be written, as the operas were written from back-to-front, with the first text being the last opera, Twilight of the Gods.

begins with three Rhine maidens who are approached by a Niebling dwarf, Alberich, who tries to woo them in order to reveal the Rhinegold (gold found in the river Rhein).

In a similar fashion, the first safe Dieter encounters, has three knobs designed to look like the Rhine maidens, and he has to crack the safe in order to find his own Rhinegold (the money inside the safe).

Die Walküre (The Valkyrie)

The second safe is based on the second opera in the Ring Cycle, completed in 1854.

The Valkyrie is an epic work in its own right. It’s over five hours long and is the birthplace of the infamous orchestral piece, The Ride of the Valkyries, which has appeared in numerous soundtracks, most notably in the 1979 American epic psychological war film, Apocalypse Now.

The engravings on The Valkyrie safe depict the story of Richard Wagner’s second opera, and Dieter correctly guesses that the knobs must be solved in the order of the story-telling.

Dieter as he cracks the safe to the accompaniment of Ride of the Valkyries, saying: “Wagner’s work had many themes of great importance to him, but all of them touched upon love.

“I believe the locks are to be solved in the order of the story and then the cycle begins anew. The themes of these stories were the model, still relevant, such as deception and double cross in love.”

Opera number three out of four of Wagner’s Ring Cycle, gives inspiration to the final safe we see cracked in this film.

Siegfried is named after the title tenor character, Siegfried, who is Siegmund and Sieglinde’s son. Siegfried grows up without parental care, and is instead raised in a foster care situation by the dwarf Alberich’s brother, Nibelung Mime.

Mime forges a sword for Siegfried in order to slay the dragon, Fafnir, and says that the dragon will teach Siegfried what fear is. This is echoed in Dieter’s fear when he attempts to crack the Siegfried safe; he is scared as he is not sure whether he will be able to break into this safe, due to his near failure with The Valkyrie, and the high-pressured situation he is in, trying to crack a safe in the back of a moving vehicle.

Dieter once again explains, in this opera, “Siegfried faces his darkest of trials in order to understand what it means to truly be afraid. He slays the dragon Fafnir and then he slays the dwarf who raised him, when confronted with his betrayal. Then he finds Brünnhilde and the two of them fall in love. After all the pain and fear, there’s a happy ending.”

This story follows a similar vein to Dieter’s own journey. His new persona of 'Ludwig Dieter' having started the film as Sebastian Schlencht-Wöhnert, was created and raised by the heist team – who would subsequently betray him in the final act. While he doesn’t slay his team, they are arrested, and he hopes the similarity between Siegfried finding love with Brünnhilde, and his own love interest in team member Gwendolyn, will be realised at the end of the film.

While not everything works out how he planned, the character of Dieter certainly follows a similar journey to the Ring Cycle’s main characters.

Götterdämmerung (Twilight of the Gods)

The fourth and final safe, is not actually seen in this film, but rather features in the first instalment of the movie franchise in Army of the Dead.

In the film, a different heist team are assembled to travel into Las Vegas, which has been overrun by Zombie’s since an outbreak six years previously.

The team are tasked with breaking into the final Hans Wagner safe, Götterdämmerung, which lies underneath the Las Vegas strip and contains $200 million, before an imminent nuclear bomb is set to destroy the city.

Due to Dieter’s experience, he is brought on as the safe-cracker, and is overjoyed to be able to join the team to fulfil his life’s purpose of cracking into the final Wagner safe. In the final act of Götterdämmerung, Brünnhilde dies in the ultimate act of self-sacrifice.

Dieter also sacrifices himself, locking his teammate, Vanderohe, in the final safe away while he is left outside with the ravenous Zombies.

Here ends the Ring Cycle of Dieter.

Who wrote the score for Army of Thieves?

The Army of Thieves score is by Hans Zimmer and Steve Mazzaro, who worked together on the recent Bond film, .

Zimmer also wrote the music for the first instalment of the cinematic universe, Army of the Dead. A wink is even given to the legendary German composer when one of the character’s describes how their brother’s favourite film is Pirates of the Caribbean, a film Zimmer scored.

The Army of Thieves soundtrack features multiple tracks from the three Wagnerian operas, and Army of the Dead features Siegfried’s Funeral March from Götterdämmerung during the safe-cracking scenes.

Netflix has been inspired to bring new audiences to classical music for the past few years, with series such as Bridgerton and Squid Game heavily featuring the genre.

As Richard Wagner and the Ring Cycle have been trending since the film premiered on 29 October, we’re excited to see how the streaming platform could bring a whole new (zombie-loving?) audience to classical music

%20(1).jpg)

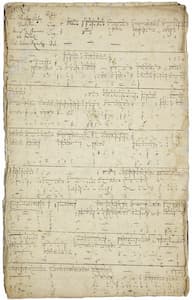

Maria Barbara Bach (1684-1720) was the second cousin of Johann Sebastian Bach. She had been orphaned at an early age and was sent to live with relatives in Arnstadt. Johann Sebastian met her after his appointment as church organist in 1703, and for a time they apparently lived in the same house, as relatives do. In 1706, Bach was severely reprimanded for inviting a “strange maiden” into the church organ loft to “make music.” Scholars today believe that the maiden in question must have been Maria Barbara.

Maria Barbara Bach (1684-1720) was the second cousin of Johann Sebastian Bach. She had been orphaned at an early age and was sent to live with relatives in Arnstadt. Johann Sebastian met her after his appointment as church organist in 1703, and for a time they apparently lived in the same house, as relatives do. In 1706, Bach was severely reprimanded for inviting a “strange maiden” into the church organ loft to “make music.” Scholars today believe that the maiden in question must have been Maria Barbara.