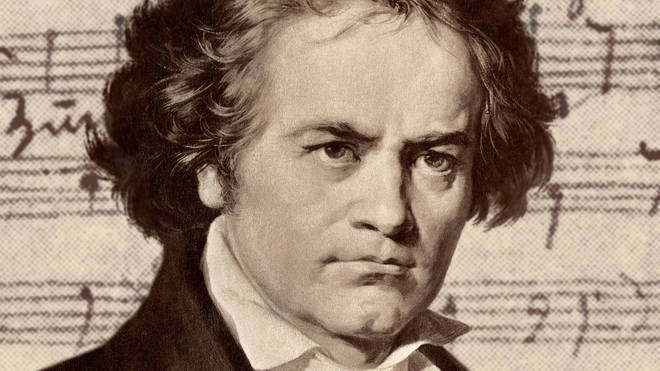

Beethoven’s previously unfinished Tenth Symphony has been completed by artificial intelligence technology. The work will have its world premiere in Germany next month, 194 years after the composer’s death.

In 1824 Beethoven premiered his final orchestral work, Symphony No. 9 in D minor.

However, before his death three years later in 1827, he had begun work on a tenth symphony.

All that remains of Beethoven’s Tenth Symphony is fragmentary sketches of the first movement which he started before his death in 1827 (read more about the here). However, these fragments have now been turned into a complete piece of music using artificial intelligence technology.

The project was started in 2019 by a group made up of music historians, musicologists, composers and computer scientists. Using artificial intelligence meant they were faced with the challenge of ensuring the work remained faithful to Beethoven’s process and vision.

Previous uses of AI in compositional processes include Schubert’s final symphony being completed by the AI from the Huawei Mate 20 Pro smartphone, and an artificial intelligence harmoniser which harmonises any melody of your choice in the style of Bach.

There have also been previous attempts to complete Beethoven's unfinished symphony. In 1988 pieced together Beethoven’s fragmentary sketches into a first movement, but was unable to go further than this section due to the limited material available.

Dr Ahmed Elgammal is a professor at the Department of Computer Science, Rutgers University, and lead computer scientist on the artificial intelligence project. He explained in The Conversation that in order for their project to go further, the team “had to use notes and completed compositions from Beethoven’s entire body of work – along with the available sketches from the Tenth Symphony – to create something that Beethoven himself might have written”.

He explained: “This was a tremendous challenge. We had to teach the machine how to take a short phrase, or even just a motif, and use it to develop a longer, more complicated musical structure, just as Beethoven would have done.”The first test was to see if an audience of experts could determine where Beethoven’s phrases ended and where the AI extrapolation began. When they couldn’t, the team knew they were on the right track.

Over the next 18 months the artificial intelligence constructed and orchestrated two entire movements, each over 20 minutes.

The entire piece will premiere on 9 October 2021 at the Telekom Forum in Beethoven's birthplace of Bonn, Germany, with a recording being released on the same day.

While the highly anticipated event is sold out, Dr Elgammal says he does expect some pushback.

“There are those who will say that the arts should be off-limits from AI, and that AI has no business trying to replicate the human creative process,” he says in The Conversation, “yet when it comes to the arts, I see AI not as a replacement, but as a tool – one that opens doors for artists to express themselves in new ways.”

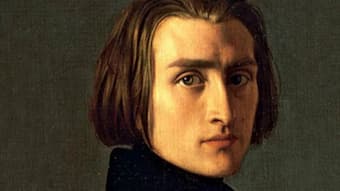

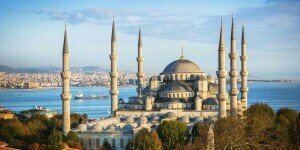

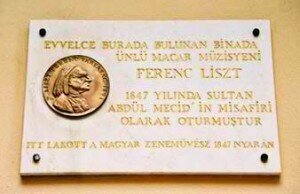

Liszt also gave a number of public concerts, including a musical matinee on 18 June at the Franchini Mansion at Buyukdere. Further private and public concerts were held at the Fethi Pasha Mansion and the Russian Embassy at Pera on 28 June. During this concert, “Liszt saw the panorama of Istanbul from the window and got really excited of seeing the east and the west at the same time. He even thought that he could seen Mount Olympus in the distance.” During his five-week stay, Giuseppe Donizetti hosted Liszt and he arranged accommodations for him at the home of the piano manufacturer Alexander Kommendinger. Donizetti had previously composed two marches for the Sultan, and at Liszt’s request, Donizetti gave him his compositions. “Liszt was in my house,” he writes. “He has just left. He wanted the notes of the two marches I composed for the Sultan. He said he was going to work them into variations sets.” Liszt first played the variations during concerts at Buyukdere on 14 and 15 June. Liszt eventually wrote out the manuscript and gave it to the Austrian ambassador, who passed it to the Minister of Foreign Affairs, who in turn presented it to the Sultan. In return, Liszt received the already mentioned enamel box studded with diamonds. Additionally, the Sultan handed Liszt a special seal, with the name of the composer written in Arabic alphabet with Turkish letters, and we do know that Liszt used it to seal a number of his letters. As it turns out, Istanbul delivered the perfect setting for Liszt to say goodbye to his life as a traveling virtuoso.

Liszt also gave a number of public concerts, including a musical matinee on 18 June at the Franchini Mansion at Buyukdere. Further private and public concerts were held at the Fethi Pasha Mansion and the Russian Embassy at Pera on 28 June. During this concert, “Liszt saw the panorama of Istanbul from the window and got really excited of seeing the east and the west at the same time. He even thought that he could seen Mount Olympus in the distance.” During his five-week stay, Giuseppe Donizetti hosted Liszt and he arranged accommodations for him at the home of the piano manufacturer Alexander Kommendinger. Donizetti had previously composed two marches for the Sultan, and at Liszt’s request, Donizetti gave him his compositions. “Liszt was in my house,” he writes. “He has just left. He wanted the notes of the two marches I composed for the Sultan. He said he was going to work them into variations sets.” Liszt first played the variations during concerts at Buyukdere on 14 and 15 June. Liszt eventually wrote out the manuscript and gave it to the Austrian ambassador, who passed it to the Minister of Foreign Affairs, who in turn presented it to the Sultan. In return, Liszt received the already mentioned enamel box studded with diamonds. Additionally, the Sultan handed Liszt a special seal, with the name of the composer written in Arabic alphabet with Turkish letters, and we do know that Liszt used it to seal a number of his letters. As it turns out, Istanbul delivered the perfect setting for Liszt to say goodbye to his life as a traveling virtuoso.