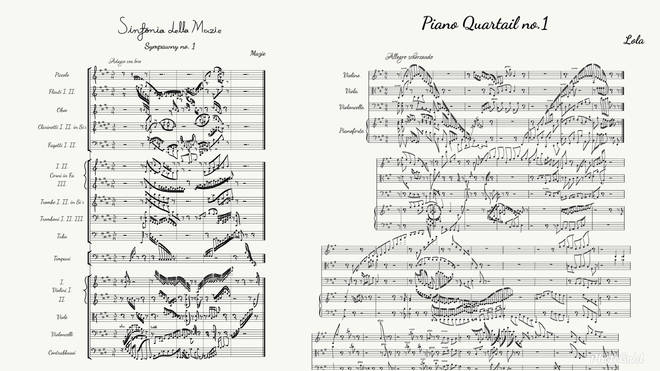

“The opportunity to study A-level music seems likely to end first for those children who are at a disadvantage,” researchers claim.

in schools is at risk of disappearing in just over a decade, researchers have warned.

Alarming new by Birmingham City University revealed the qualification could have zero entries by 2033, following years of cuts to local and central government funding.

In the report, it was confirmed that a rapid decline in access to A level music in state schools, means the subject is increasingly available only to pupils with an independent school education.

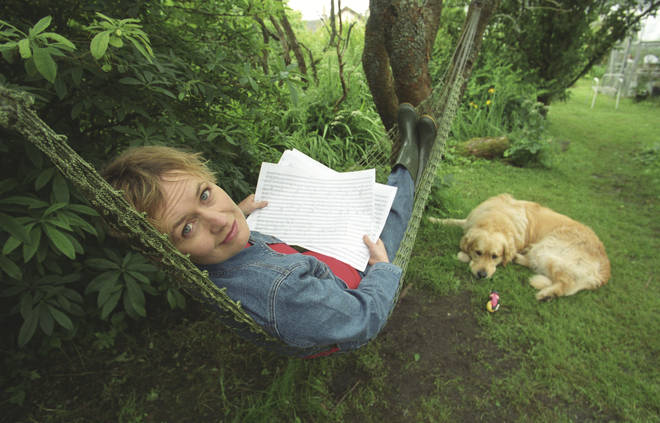

Lead researchers Dr Adam Whittaker and Professor Martin Fautley’s study is now galvanising music academics and industry bodies to call for urgent action and improved policy and funding, to support music provisions in state schools.

Dr Whittaker said: “We know from trends in A-level uptake over the last few years that the number of pupils taking A-level music has fallen to a very concerning level.

“We are now in a position where there are parts of the country with very limited access to A-level music or, in some cases, no access at all.

He continued: “Children can’t choose a qualification that isn’t offered to them. What is the child who wants to take A-level music to do if the nearest school offering it is 30 miles away? We need A-level music, and other specialist subjects, to be offered in a range of schools right across a local authority area.

“This is important as A-level music can support young musicians to pursue music in higher education and their future careers, including as the next generation of music educators.”

Whittaker and Fautley warned that looking at the current rates of decline, A level music is likely to have zero entries by 2033.

“Those who lack the means to support private instrumental study are unlikely to have sufficient income to pay for independent school fees, even if a bursary supports them to a greater or lesser extent,” they added.

The report also revealed that independent schools have a much higher number of A level music entries, narrowing the potential pool of young music talent.

In the Midlands, the proportion of students in the Midlands studying music has dropped to one percent, due to schools and colleges no longer offering the subject at all.

In an interview last year for Black Lives in Music, star cellist Sheku Kanneh-Mason, who went to a state school in Nottingham, warned opportunities for ethnically diverse young musicians are worsening because of state arts education cuts.

“The cuts that have been [made] to music at my primary school have been devastating – and as a result, there are few children who are able to have this music education,” he said

“You create this two-class thing where those able to pay for music lessons are able to become musicians and be enriched by these wonderful experiences. There’s a massive divide in this country in opportunities. It highlights a really big problem in this country.UK- Music chief executive Jamie Njoku-Goodwin said: “There has been a worrying decline in the number of young people studying music at A-level in recent years. Unless action is taken to reverse that trend, there is a real risk of serious damage to the talent pipeline on which the music industry relies.

“Music education enriches the lives of countless children and young people, but it also brings huge cultural, economic and social benefits to the UK.

“At UK Music, we are continuing to talk to the government and education leaders about how we can ensure that children from every background get the best possible chance to study music which is one of our great national assets.”

In a separate report by the Department for Education, ‘Music education: call for evidence’, it was found that many young people, despite holding an interest in pursuing music as a career, are feeling pressure to choose other subjects because GCSE or A level music are not options in their schools.