It's all about the classical music composers and their works from the last 400 years and much more about music. Hier erfahren Sie alles über die klassischen Komponisten und ihre Meisterwerke der letzten vierhundert Jahre und vieles mehr über Klassische Musik.

Total Pageviews

Tuesday, November 16, 2021

My passion of music (VI)

Sunday, November 14, 2021

Classical Romance: The Sweetest Love Stories of Classical Music Composers

by Hermione Lai, Interlude

© Carnegie Hall Corporation

I am not a great fan of tabloid or boulevard journalism. Surely you have seen these colourful publications at checkout counters in your local supermarket and elsewhere. Most carry outrageous headlines of alien invasions or some poor souls doing something unspeakable to themselves or other. But I must confess, when it comes to love and romance stories involving the rich, handsome and famous, I get all excited. Please don’t blame me. Tales of classical romance are not a new invention, as everybody wanted to know about the love life of yesteryear’s superstar, including classical music composers. So we decided to take a look at the most famous glamour couples in classical music. Get ready for some classical romance involving 10 famous classical music composers.

Gustav Mahler and Alma Schindler:

Gustav Mahler and Alma Schindler

Alma Schindler was Vienna’s most desired bachelorette at the turn of the 20th century, and she knew it. She was utterly obsessed by a sense of entitlement that the world owed her something in return for her brilliance and her beauty. She was well read, highly educated, and an accomplished pianist and composer. Alma was drawn to older men with artistic credentials, intellect, creativity, and money, and she attracted them like flies. Gustav Mahler was engaged as conductor at the imperial opera, and they had a huge argument when they first met at a dinner party. Mahler was conducting an opera of her ex-lover Alexander Zemlinsky, and Alma told him exactly what he should do. They couldn’t agree and met at the opera the following day to iron out their differences. A whirlwind courtship soon ensued, and Gustav proposed marriage on 21 December 1901. The couple was formally married at a private ceremony on 9 March 1902, with Alma already carrying their first child, Maria Anna. The relationship wasn’t a bed of roses, but Mahler composed the famous “Adagietto” from his 5th Symphony as a love song without words for Alma. Classical romance doesn’t get any better than that, don’t you think? Johann Sebastian Bach and Anna Magdalena Wilcke:

Johann Sebastian Bach and Anna Magdalena Wilcke

When Johann Sebastian Bach returned to Cöthen from a lengthy trip to Carlsbad, he was told that his wife Maria Barbara Bach had died at the age of 36. Carl Philip Emanuel reports, “My father returned to find her dead and already buried.” It was a tremendous shock not only to Johann Sebastian, but also to four motherless children. Johann Sebastian dealt with his grief by composing tirelessly, and for special feast days singers from nearby Courts were enlisted to strengthen the local choir. One such singer was Anna Magdalena Wilcke, and a classical romance soon ensued. They were first seen together as godparents at a child’s christening. Bach was 36 and Anna Magdalena 20, and apparently he was attracted by her fine soprano voice, among other things. The couple married on 3 December 1721, and to celebrate the occasion, Bach went twice to the city cellars and bought two small casks of Rhine wine. Anna Magdalena was an accomplished musician and deeply involved in her husband’s musical tasks. To show his appreciation, Johann Sebastian put together a little notebook of music specifically dedicated to his wife. Recently, it has been suggested that it was Anna Magdalena who actually composed some of the pieces in this little notebook. How delightful, two classical music composers and lovers writing music for each other.

Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart and Constanze Weber:

Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart and Constanze Weber

Among classical music composers, Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart rates as one of the top musical geniuses. And his classical romance with Constanze Weber was definitely a high-profile topic for the tabloid press. Mind you, Mozart’s eye initially fell on Aloysia Weber, Constanze’s sister. She was a well-known soprano and became Mozart’s student and lover. He really wanted to marry her, but his father sent him on a long tour to Paris. When he came back several months later, Aloysia pretended that she didn’t even know him. As you can imagine, Mozart wasn’t particularly happy and he had some choice words for his ex-lover. Her sister Constanze wasn’t even on his radar, but all that changed when he became a lodger in the Weber household in Vienna. Mozart wanted to stay for only a week, but as he fell in love with 19-year-old Constanze, he stayed for several months. Her mother wasn’t happy about the courtship and neither was Mozart’s father. The couple broke up for a short period of time but got married on 4 August 1782 at St. Stephen’s Cathedral in Vienna. Mozart writes to his father, “Tell me whether I could wish for a better wife.” Constanze was a trained singer, and her husband wrote several compositions specifically for her clear soprano voice.

Ludwig van Beethoven and Therese Malfatti:

Ludwig van Beethoven and Therese Malfatti

Ludwig van Beethoven wasn’t lucky in love. I think it was actually his own fault. He kept falling in love with women of high social standings, or women already married to somebody else. And let’s not forget the countless times he fell in love with his beautiful and young students. Therese Malfatti was 18 and Ludwig 40, and it seems that he mistook her admiration and devotion to be love. Beethoven was actually serious about marrying Therese, because he asked a good friend to forward his birth certificate from Bonn, which would have been required for marriage. An anecdote tells of the story when Beethoven was invited to the Malfatti household in 1810 to a cocktail party. Beethoven apparently wanted to propose to Therese and composed a special bagatelle for her. In the event, Beethoven got seriously drunk and forgot all about playing or proposing. He never summoned the courage to ask for her hand in marriage again, and Therese married an Austrian nobleman in 1816. Beethoven writes, “Now fare you well, respected Therese. I wish you all the good and beautiful things of this life. Bear me in memory—no one can wish you a brighter, happier life than I—even should it be that you care not at all for your devoted servant and friend.” How is that for a classical romance that never was?

Robert Schumann and Clara Wieck:

Robert and Clara Schumann, 1847

Among classical music composers, the love story of Robert Schumann and Clara Wieck is unique and touching. Schumann initially moved to Leipzig to study law, but soon found that he wanted to take piano lessons from Friedrich Wieck, probably the most prominent teacher in Leipzig at that time. As was customary, Schumann moved into the house of his piano teacher and really enjoyed his time in the big city, and with the servant girls. At the same time, Wieck was grooming his daughter Clara to become a star pianist, and he controlled every aspect of her life. He not only coached her musically, but also dressed her and even wrote her diary for her. Robert was twenty-five when he fell in love with sixteen-year old Clara. Wieck wanted his daughter to stay well clear of Schumann, and when they got secretly engaged in 1836, he threatened to shoot Robert if Clara should ever mention his name again. He also scheduled Clara’s next musical appearances far away from Leipzig. In the end, the matter went before the courts and after a long period of nasty legal battles and bitter fights, Robert Schumann finally married Clara Wieck on 12 September 1840, the day before her 21st birthday. That’s what I call a classical romance with a happy end; at least initially.

Johannes Brahms and Clara Schumann:

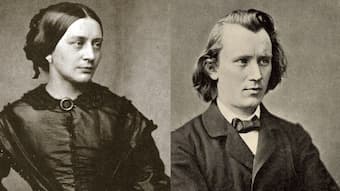

Johannes Brahms and Clara Schumann

In the history of classical music composers, Robert Schumann, Clara Schumann, and Johannes Brahms are surely the most famous love triangle. Brahms first visited the Schumann’s in 1853, and Robert helped him to get his career started. Robert had been hearing voices in his head for some time, and after attempting to take his own life he was admitted to a mental hospital. Brahms rushed to Clara’s side and was allocated a bedroom on a separate floor in the Schumann house. He was head over heels in love with Clara, but the situation was seriously messy. Schumann was Brahms’ hero, Clara was taking care of seven children, and then there was the age gap. She was 35 and Brahms was 21, and both were raked by feelings of anxiety and guilt. Every tabloid wanted to know if they actually had become lovers, and that question is still debated today. For what it’s worth, I don’t think they ever did because in Brahms’ mind Clara had become a saintly figure that stood well above earthly matter. And we do know that he had the deepest respect for her as an artist and as a woman. Once Robert died in 1856, Brahms and Clara were free to marry, however, Brahms ruthlessly turned her away. Neither of them married anybody else, and they retained an inescapable platonic connection for the rest of their lives. Clara focused on her performances and Brahms became a grumpy old composer.

Franz Liszt and Marie d’Agoult:

Franz Liszt and Marie d’Agoult

When we talk about classical romance among classical music composers the name Franz Liszt automatically receives top billing. The tabloid press absolutely loved him, and reports of his serial conquests made headlines wherever he went. Generally portrayed as a wicked womanizer, Liszt actually seemed to have preferred stable long-term relationships. And one of the most important relationships of his early life brought him together with the Countess Marie Catherine Sophie d’Agoult. She was married to an ancient and crusty war veteran, and she sang in a women’s choir in 1833. The guest of honor was the spectacular pianist Franz Liszt. Marie writes in her memoirs, “I use apparition because I can find no other word to describe the sensation aroused in me by the most extraordinary person I had ever seen. He was tall and extremely thin. His face was pale and his large sea-green eyes shone like a wave when the sunlight catches it. Franz spoke with vivacity and with an originality that awoke a whole world slumbering in me.” Marie had been slumbering for sure, as she described herself as “six inches of snow covering twenty feet of lava.” Since Marie was married, they had to leave Paris and in the second volume of “Years of Pilgrimage,” Franz Liszt musically recalled some of the emotionally fulfilling days of traveling with Marie. The couple had a number of children, and Cosima Liszt, born in December 1837, is part of our next famous classical romance.

Richard Wagner and Cosima Liszt-Bülow:

Richard Wagner and Cosima Liszt-Bülow

Talking about another famous love triangle involving classical music composers. Cosima Liszt had a difficult childhood. She was an illegitimate child and her father a traveling virtuoso. Liszt and the Countess Marie d’Agoult had long separated, and that separation hadn’t been amicable at all. As such, Cosima was first raised by Liszt’s mother, and then placed into the care of Franziska von Bülow. Her son Hans was one of Liszt’s best students and he fell in love with Cosima. Franz Liszt was delighted and the couple married in August 1857. During their honeymoon they visited Richard Wagner in Zürich, as Hans had seduced the teenage Cosima to the strain of Wagner’s Tannhäuser. A social relationship developed quickly, and Hans became one of the most enthusiastic supporters of Wagner’s music. That enthusiasm was strained however, when Wagner—who was still married to Minna—and Cosima became lovers in 1862. In due course, Cosima gave birth to three Wagner children, and she obtained a divorce from Bülow in 1870. Wagner’s wife had since passed away, and thus Richard and Cosima married in August 1870. Cosima was completely devoted to her husband’s artistic cause, and they settled in the small town of Bayreuth. The first Wagner Festival took place in 1873, and Bülow became one of the most enthusiastic supporters of Brahms’ music. The mysterious ways of classical romance make for some very interesting stories.

Hector Berlioz and Harriet Smithson:

Hector Berlioz and Harriet Smithson

On rare occasions, an important classical romance is actually translated into music. Such is the case with Hector Berlioz’s Symphonie fantastique, an autobiographical and self-confessional work. It is a symphonic exposé of his unrequited love for the Irish Actress Harriet Smithson. He first saw her in the role of “Ophilia” in Shakespeare’s Hamlet during the 1827-1828 Season. Berlioz was immediately besotted with Harriet, and his obsession grew into a proper act of stalking. He sent her flowers, wrote her numerous letters and even rented an apartment near hers so he could watch her coming and going. And Harriet predictably avoided him like the plague! Berlioz confessed that he “pined for her, lusted for her, suffered, hankered, thirsted and ached for her, and he dreamt of no one but her.” And Berlioz began writing Harriet into his music as well. Essentially, the Symphony Fantastique of 1830 is about an artist who is madly in love with a woman who does not know he exists. He invited Harriet to the premiere, but she did not show up. It took Harriet almost two years to understand that this symphony, and the sequel Lélio, was all about her. She now contacted Berlioz, and he came for a visit. They finally became lovers and were married in October 1833 at the British Embassy in Paris. Imagination tends to be much easier to handle than reality, and this classical romance turned sour in a real hurry.

Benjamin Britten and Peter Pears:

Benjamin Britten and Peter Pears

For a classical romance of more recent times we turn to Benjamin Britten and Peter Pears. Pears had won a scholarship to the Royal College of Music in London, and through a mutual friend, was introduced to Benjamin. A strong friendship quickly developed, and within weeks of their first meeting Britten composed a song for Pear’s tenor voice and strings. They moved in together shortly thereafter, and by the time they arrived in the New World in 1939, they had become lovers. Their highly affectionate personal and professional relationship lasted for almost forty years, until Britten’s death in 1976. Peter Pears was Britten’s great love, but he was also his great inspiration. As such he featured prominently in many of Britten’s works, including Peter Grimes, Albert Herring, The Turn of the Screw, and the War Requiem. The couple also founded the Aldeburgh Festival in 1948, and established the Britten-Pears Young Artist Programme. Neither Pears nor Britten ever spoke publically about their relationship or sexuality. You can’t really blame them, as homosexuality was illegal in Britain until 1967. Pears summed up the relationship in 1980, “ours was not the story of one man. It was a life of the two of us.”

Thursday, November 11, 2021

ABBA give an unexpected nod to Tchaikovsky’s Swan Lake in new ‘Voyage’ album

By Sophia Alexandra Hall, ClassicFM London

@sophiassocialsWhile an ABBA x Tchaikovsky collaboration wasn’t on our bingo cards for 2021, we’re kind of here for it...

Swedish pop group sensation ABBA are back after a 40-year hiatus with their ninth and final studio album, Voyage.

And fans have noticed that the final track on the album, Ode To Freedom, has a familiar tune.

Not because it contains a call-back to a previous song composed by the band, but rather because the song references the the Waltz from Tchaikovsky’s ballet, Swan Lake.

Written by the Russian composer between 1875-76, Swan Lake is one of the most popular ballets of all time, and the Waltz in A flat major is one of the most recognisable melodies from the work.

Twitter was quick to pick up on the reference to the tune in ABBA’s final Voyage track, with listeners desperately trying to find the piece of classical music they were reminded of...

Despite its references to the waltz, Ode to Freedom is written in a time signature of 4/4, instead of the expected 3/4 found in Swan Lake, and the majority of other waltz forms.

Thus, the theme is pulled into a more conventional pop song format, while maintaining the low swelling string holding the melody similar to the original Tchaikovsky.

The vocals enter towards the end of the song, joining in on a typical ABBA-esque harmonic build on the main melody with the following lyrics.

The foursome sing about writing an ‘Ode to Freedom’, a piece of music ‘not pretentious, but with dignity’. In the ballet, the waltz underscores Prince Siegfried’s birthday; it is a moment of celebration for our principal dancer as he celebrates with his friends and villagers from his kingdom.

It seems fitting that Abba’s final album should end with an epic orchestral, albeit gentle, celebratory theme.

The band has achieved so much since forming in 1972, and they have every right to celebrate a long and successful career where they changed the face of the pop music industry forever.

Symphonies by Female Composers Kaprálová, Beach, Auner, Mayer, Larsen, and Pavlova

by Georg Predota, Interlude

Vítězslava Kaprálová

Vítězslava Kaprálová (1915-1940) was one of the most impressive and exciting musical voices at the beginning of the 20th century. She wrote her first compositions for piano solo at the age of nine, and graduated from Brno Conservatory with a piano concerto, which she conducted herself. She was able to secure a French government scholarship, and after her move to Paris she studied conducting with Charles Munch and composition with Bohuslav Martinů. The compositions she wrote in Paris showed every sign that she was on the verge of becoming a major musical figure in the 20th century. Her works reveal “a mature mastery of contemporary musical language as she mingles a concise polytonality with her own melancholy melodic expression.” Kaprálová shared the limelight with Béla Bartók, Alban Berg, Benjamin Britten, Aaron Copland, and Paul Hindemith at the International Society of Contemporary Music Festival in 1938. Her Military Sinfonietta actually was chosen to open the festival, and she quickly received international critical acclaim. Two months after her marriage to Jiří Mucha, the son of the Art Nouveau artist Alphonse Mucha, Kaprálová died after a brief illness on 16 June 1940.

Despite her death at 25, she left behind “a remarkable array of more than 50 works of virtually every genre. Almost all of them are of the highest craftsmanship and inspiration.” Her Military Sinfonietta serves as an important testament to the anxieties of the times, and it sparkles with colorful orchestration, fine craftsmanship, passion and great musical sensitivity. The composer described the work as “using the language of music to express the emotional relationship toward the questions of national existence… The composition does not represent a battle cry, but it depicts the psychological need to defend that which is most sacred to the nation.” Kaprálová’s life has inspired two Czech language monographs and two novels, and her compositions—ranging from art songs to orchestral cantatas—must become part of the musical mainstream.

Amy Beach

Amy Beach (1867-1944) was the first American woman to succeed as a composer of large-scale art music. An exceptional musical prodigy, “she could sing 40 tunes accurately at the age of one; before the age of two she improvised alto lines against her mother’s soprano melodies; at three she taught herself to read; and at four she mentally composed her first piano pieces and later played them, and could play by ear whatever music she heard, including hymns in four-part harmony.” She gave her successful debut in Boston on 24 October 1883 playing the E-flat Rondo by Chopin and the G-minor Concerto by Moscheles. In terms of composition, she was essentially self-taught and started publishing her works in the mid 1880s. Her early works show a remarkable sensitivity to the relationships between music and text, and song is always at the core of her style. Beach had no problems mastering extended musical forms, including her “Gaelic Symphony” premiered by the Boston Symphony Orchestra in 1896. Her colleague George Whitefield Chadwick famously wrote to her after the premiere, “I always feel a thrill of pride myself whenever I hear a fine new work by any one of us, and as such you will have to be counted in, whether you will or not—one of the boys.” It was the first symphony composed and published by an American woman, and Beach became one of the most respected and acclaimed American composers of her era. She published well over 300 works during her lifetime and included almost every genre. It is inconceivable and shameful that we don’t hear her music with greater regularity.

Mary Dickenson-Auner

The Irish violinist, music educator and composer Mary Dickenson-Auner (1880-1965) initially took violin lessons with Samuel Coleridge Taylor, and she continued her education at the Royal Academy of Music in London. During her career as a professional violinist, she performed the world premiere of Béla Bartók’s Violin Sonata No. 1. A critic wrote, “To Mrs. Dickenson-Auner also fell the distinction of being chosen by Béla Bartók for the first performance anywhere of his new Violin Sonata, which is still in manuscript. This composition, which has since been performed in London as well, created a deep impression here by virtue of its strongly personal and national touches. An equal share of admiration fell to the lot of Mrs. Dickenson-Auner and to her partner, Eduard Steuermann, a Viennese pianist from the Schoenberg group, who, in their interpretation of this piece, displayed remarkable technical resources and admirable interpretative powers.” In addition, Dickenson-Auner joined Arnold Schoenberg’s private music performance group and gave concerts under his direction. During the tumultuous times of WWII, she turned towards composition and published her early works under the pseudonym Frank Donnell. In all, Auner wrote six symphonies, four operas, two oratorios and numerous songs and chamber music works. Her compositions combine her love for Johann Sebastian Bach with the 12-tone music of Schoenberg. Auner found her musical inspiration in Irish folk tunes of her early years, tellingly calling the resulting compositions “Celtic Impressionism.”

Emilie Mayer

Emilie Mayer (1812–1883) is not a household name. However, she was an extraordinary figure in the social and musical history of her era, “and one of the very first women composers to make a profession of her proclivity for creative work; Emilie Mayer saw herself primarily as a composer.” A biographer wrote, “Her financial independence was a prerequisite that allowed her to escape gender-specific social conventions and lead the life of a freelance composer.” Born in a small town in the Duchy of Mecklenburg-Strelitz, Mayer revealed her musical talent early on and composed waltzes and sets of variations. Relocating to Stettin, Mayer auditioned Carl Loewe for compositions lessons, and he attested to her “God-given talents.” She started to compose in earnest, and the local Orchestral Society performed her first two symphonies. Mayer relocated to Berlin and became a professional composer. The public response to her works was thoroughly positive, “but equally thoroughly pervaded by a gender-specific caveat summarized by a critic for the Neue Berliner Musikzeitung… That still other abilities and a more elevated intellect are necessary in order to probe the deepest mysteries of art need hardly be stated. That which female powers – powers of a second order – are capable of attaining, Emilie Mayer has achieved and brought to expression.” Undeterred, she continued to organize concerts of her music, but the great Berlin and Leipzig publishing houses were not interested to issue her orchestral works. As such, Mayer shifted her focus to string quartets, duo sonatas and character pieces and sometimes financed the publication herself. One of the first professional female composers, Emilie Mayer primarily composed instrumental music, and that includes eight symphonies. That such an exceptional pioneer of the arts should have been summarily dismissed and forgotten is an indelible stain on the way we record and remember history.

Libby Larsen

Libby Larsen is one of America’s most-performed living composers. Her catalog contains more than 400 works spanning virtually every genre from intimate vocal and chamber music to massive orchestral works and more than 15 operas. Her music has been praised for its dynamic, deeply inspired, and vigorous contemporary American spirit. Grammy Award winning and widely recorded, including over fifty CD’s of her work, she is constantly sought after for commissions and premieres by major artists, ensembles, and orchestras around the world, and has established a permanent place for her works in the concert repertory. During the early stages of her career, Larsen was determined to work independently. Rather than working in academia, she enjoys the collaborative process of working with performers, and believes “that her works are only complete when performed for an audience.” For Larsen, the process of composition is not an isolated intellectual activity. “I view composition as a generative activity,” she explains, “that I approach by living fully in the world and bringing whatever insight I have about the world I live into my music. In that way I can’t separate myself from my music, nor do I separate myself from society. I don’t expect that society would have to come to my music; since I’m part of society, my music should be immediately part of that society.” Larsen is greatly influenced by the rhythms and pitches of spoken American English, and she describes composition as “placing sounds in order in time and space.” Contrasting styles of music represent different segments of the community, “and rhythmic vitality and a wide palette of tonal colors, which may include electronically generated or amplified sounds,” are trademarks of Larsen’s style. She considers all types of music “from choral and orchestral to boogie woogie, jazz, and rock and roll, to be different combinations of pitch and rhythm that reflect contemporary culture.” Larsen continues to share her thoughts on music and the arts in keynote addresses throughout the United States.

Alla Pavlova

The composer and musicologist Alla Pavlova started her musical career in Moscow. After spending some time in Sofia, she moved to New York. Pavlova has special interest in writing music for film, theater, dance, and children. The orchestra seems to be her preferred medium, and she has 11 symphonies to her name. However, a number of her instrumental and vocal works have also been performed in the United States, Europe, and Canada. Her 2nd Symphony “For the New Millennium” was composed in 1997 and subsequently revised. The composer writes, “The idea of the symphony is of man and his relation to the Universe on the threshold of the new millennium. The first movement and finale express man’s subjective perception of he Universe, and this is why violin solos play an important role in these movements. The second and third movements picture the Universe, with its forces of Light and Darkness, which are always in opposition to each other, but at the same time complement each other… The essence of the symphony in its entirety is the necessity of human striving toward Light and Love, no matter how tragic the reality may be.”

Sunday, November 7, 2021

My passion of music (V)

Friday, November 5, 2021

Robert Schumann: Paradise and the Peri, Op. 50

by Georg Predota, Interlude

Robert Schumann © Wikipedia

When Robert Schumann premiered his secular oratorio Das Paradies und die Peri, Op. 50 (Paradise and the Peri) in December 1843 in Leipzig, the composer was instantly catapulted from provincial to international fame. In the first decade after the composition, the Peri was performed more than fifty times. Schumann even called it his “greatest work,” and his wife Clara suggested, “It seems to me the most magnificent he has written yet.”

Although the work was a resounding success with audiences and critics alike, it quickly disappeared from the repertoire and has been unable to gain a foothold in the modern concert hall. A number of commentators have wrongly located the primary reason for the work’s neglect in the “flowery, Eastern-inspired verbiage of the libretto.” The subject matter is loosely based on one of the four lengthy poems from Thomas Moore’s oriental epic the Lalla Rookh. Originating in Persian mythology, the text strongly resonates with contemporary enthusiasm for oriental impressions that is reflected in light fiction as well as serious literature.

The story centers on the heroine Peri, who is seeking admission into paradise, a realm from which she has been excluded owing to her mixed descent from the union of a fallen angel and a mortal. Peri can enter the heavenly pastures only if she is able to render “the heaven’s dearest gift.” To gain admission, Peri captures the last drop of blood of a young freedom fighter in India, and in Egypt she catches the last breath of a girl who sacrifices herself for her plague-ridden lover. Both gifts, however, are not sufficient. Only the tear of a Syrian criminal, shed in remorse at the sight of a praying child, finally opens the gates of heaven. Richard Wagner enthusiastically wrote to Schumann in 1843, “I do not only know this wonderful poem, it has also been passing through my musical senses; but I found no form with which to reproduce the poem, and therefore I now wish you the luck to have found the right one.”

The work is clearly the product of Schumann’s ever-fertile interest in literature and allegory. Above all, Schumann was looking to create an oratorio “not for the chapel, but for merry people.” In a musical sense, he blended elements from the oratorio, opera and song. Internally, the work is held together by lyrical quasi-recitative that propels the narrative portions of the text. Since it contains a number of memorable tunes, Schumann was quickly accused of pandering to popular taste. But it was not the choice of text or Schumann’s musical treatment that plunged the work into obscurity. Rather, it all had to do with a subtle change in the inner constitution of concert life. While church music is primarily sustained by the institution, secular non-theatrical music was aligned with notions of education, culture and good breeding. The educated classes in the 19th century extended from the lesser nobility to academics and the working middle classes. Compositions for mixed chorus represented the educated classes, and choral societies formed throughout Europe that would perform at specific times during the year in large musical festivals. Since secular vocal music was closely linked with the spirit and institution of the public concert, it only took some minor changes in social conventions and attitudes to make the entire repertory disappear into oblivion. Maybe the early 21st century is once again sensing the need for a closer connection between the public concert and the educated classes. Whatever the case may be, it is decidedly satisfying to witness the revival of this once highly popular secular choral repertory.

The work is clearly the product of Schumann’s ever-fertile interest in literature and allegory. Above all, Schumann was looking to create an oratorio “not for the chapel, but for merry people.” In a musical sense, he blended elements from the oratorio, opera and song. Internally, the work is held together by lyrical quasi-recitative that propels the narrative portions of the text. Since it contains a number of memorable tunes, Schumann was quickly accused of pandering to popular taste. But it was not the choice of text or Schumann’s musical treatment that plunged the work into obscurity. Rather, it all had to do with a subtle change in the inner constitution of concert life. While church music is primarily sustained by the institution, secular non-theatrical music was aligned with notions of education, culture and good breeding. The educated classes in the 19th century extended from the lesser nobility to academics and the working middle classes. Compositions for mixed chorus represented the educated classes, and choral societies formed throughout Europe that would perform at specific times during the year in large musical festivals. Since secular vocal music was closely linked with the spirit and institution of the public concert, it only took some minor changes in social conventions and attitudes to make the entire repertory disappear into oblivion. Maybe the early 21st century is once again sensing the need for a closer connection between the public concert and the educated classes. Whatever the case may be, it is decidedly satisfying to witness the revival of this once highly popular secular choral repertory.