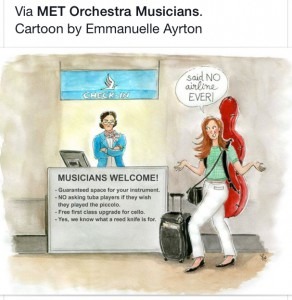

by Janet Horvath, Interlude

Cello en route

Recently a guitarist had his custom-built instrument safely stowed in the overhead bin on a flight to Nice. The stewardesses approached him in a funk. Despite his explanations as to why the guitar needed to be there, the cabin crew refused to listen and took the instrument away from him. Inevitably it arrived on the luggage belt in Nice smashed to pieces.

Longtime concertmaster of the Pittsburgh Symphony, Andrés Cárdenes had a rude experience recently. “Just when I start thinking the airlines understand the law regarding violins as carry-on, the B35 gate agent in Pittsburgh tells me I can’t carry it on, nor would it fit. I immediately argued, whereupon she began laughing at me. Fortunately, I carry a copy of the law in my case and showed her. She then proceeded to ignore me as I tried to enter my frequent flier number—ignorant and disrespectfully rude. Nice job description, American Airlines.”

Another colleague recently flew Ryanair, Cologne to Madrid. He boarded. The crew immediately told him he couldn’t store the violin in the overhead compartment due to security reasons. (That’s a good one!) After having shown them that he actually paid an extra 50 EUROs to have the violin in the cabin, they claimed that he had to have an extra seat. After much discussion, they finally gave him two seats, the violin held by a mandatory seat belt. Indeed I suppose this would be more ‘secure’ than in the bin above. Principal cello of the Cleveland Orchestra Mark Kosower got the seatbelt treatment. Note the elaborate harness on his most recent flight—a very safe cello on Air Canada.

Andreas’ violin on board

But their language still leaves a musician in a quandary:

‘Due to passenger loads, aircraft limitations and/or storage space available, we cannot guarantee that a musical instrument can be accommodated on board. It may need to be checked at the gate and transported as checked baggage. For this reason, musical instruments must always be properly packaged in a rigid and/or hard shell container specifically designed for shipping such items.

Piano on plane

Meanwhile, Robert Black, a member of the Bang on a Can All-Stars, who perform all over the world, somewhat confidently loaded his double bass onto a flight from Fortaleza, Brazil, to New York on TAM the largest airline in Brazil. When he arrived there was no sign of the bass! Days later the airline still had no idea where the bass was. At his wits end Black posted several photos and the following on social media:

“The bass is one of Patrick Charton’s B-21 models he made for me in 2009 (No. 13). It is a very unique and distinctive instrument. There are only about thirty of these instruments in the world. It easily stands out and cannot be confused for any other bass. There is a unique dedication inscribed inside.”

Amazingly enough, due to the Facebook photos, a colleague noticed the bass sitting in a locked office at the international baggage claim in Toronto, Canada. Yes Canada—from Brazil. He took a photo of it and sent the photo to Black who forwarded it to TAM airlines. No mea culpa from the airlines for several more days until finally the bass was shipped directly to the artist’s home in Harford, Connecticut via Federal Express from Toronto, undamaged.

On a routine trip home from Tokyo to Germany Japanese violinist Yuzuko Horigome’s Guarneri violin was seized at the Frankfurt airport. Apparently she had not shown the proper documents nor had she declared her $1.2 million violin. It would be held until she paid the fine of 190,000 euros ($238,400) in import duties. The violin was eventually returned and Horigome was spared the fine. But what agony!

In another instance Yuki Manuela Janke was returning home to Germany after giving a performance in Tokyo, when customs officers at the Frankfurt airport confiscated her 1741 Stradivarius violin worth $7.6m claiming Janke might plan to sell it. If she wanted it back she’d have to pay $1.5m customs duty. The instrument known as ‘The Muntz’ violin had been leased to Janke since 2007 and the owners, the Japan-based Nippon Foundation, indicated that Janke had documentation, including her loan contract with the foundation, photographs of the violin, and other papers.

In another instance Yuki Manuela Janke was returning home to Germany after giving a performance in Tokyo, when customs officers at the Frankfurt airport confiscated her 1741 Stradivarius violin worth $7.6m claiming Janke might plan to sell it. If she wanted it back she’d have to pay $1.5m customs duty. The instrument known as ‘The Muntz’ violin had been leased to Janke since 2007 and the owners, the Japan-based Nippon Foundation, indicated that Janke had documentation, including her loan contract with the foundation, photographs of the violin, and other papers.

The lesson here is that one cannot be too careful! Carry the papers for your instrument and check each airline’s policy carefully. Print these policies. If you can, talk to a supervisor beforehand and get their name. (The U.S. Policy is downloadable below.) Arrive early to every flight. If the worst does happen and you must check your instrument, loosen the strings, and stuff the case with clothing so the instrument is padded and tightly held. Insist on claiming it at the tarmac rather than allowing it to descend on the conveyor belts. Put fragile and “this side up” stickers all over the best hard case that you can afford. Consider shipping via ground. Here also are links to the how to’s of shipping.

Stay tuned for the agony of ivory.