By Fanny Po Sim Head, Interlude

Because my mouth

Is wide with laughter

And my throat

It is deep with song

You do not think

I suffer after

I have held my pain

So long?

Because my mouth

Is wide with laughter

You do not hear

My inner cry?

Because my feet

Are gay with dancing

You do not know

I die?

These are Minstrel Man’s lyrics, the first piece of Three Dream Portraits composed by Margaret Bonds. I discovered Bonds through playing this piece for a singer. The emotional text accompanied by a relatively straightforward piano part creates a powerful effect and led me to want to know more about her and her music.

Margaret Allison Bonds

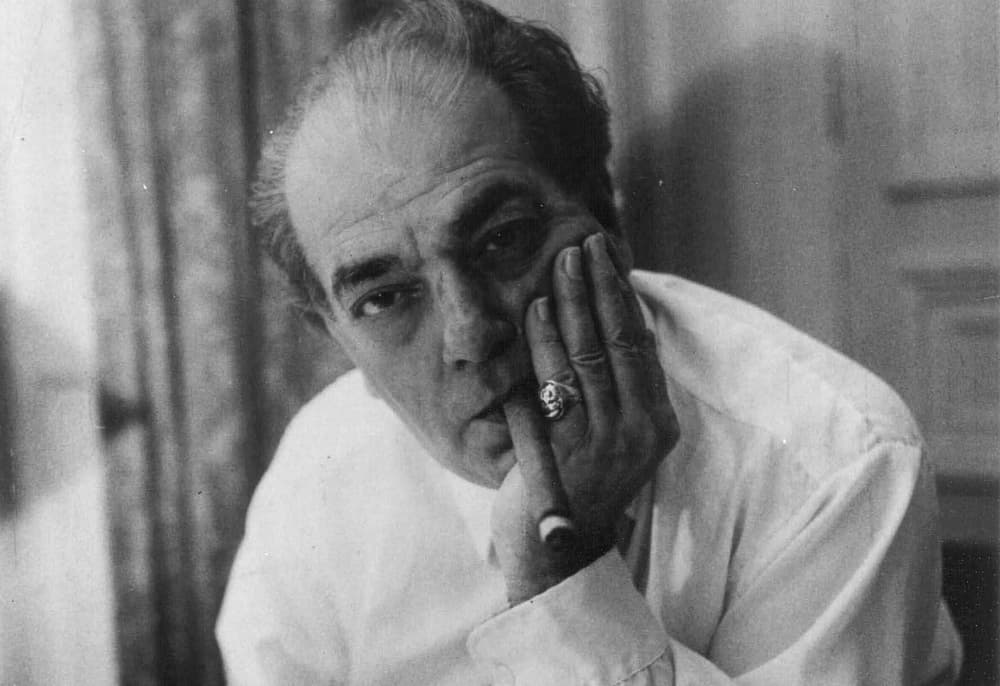

Margaret Allison Bonds (1913-1972) was born in Chicago, the United States. Her parents, Estrella Bonds and Dr. Monroe Majors were divorced when Margaret was very young. While her mother and her grandmother raised Margaret, she remained close with her father. Dr. Monroe Majors (1864-1960) was a physician, a writer, and a civil rights activist. He opened one of the first black hospitals in Texas. One of his popular publications, Noted Negro Women: Their Triumphs and Activities, acknowledges the accomplishments of black women since the end of slavery in the 1860s. Margaret had once collaborated with her father for his campaign song We’re All for Hoover Today.

Margaret Bonds took piano lessons from her mother when she was little. Estrella Bonds was a renowned piano teacher. She was also a charter member of the National Association of Negro Musicians (NANM). Margaret Bonds grew up meeting many African American artists and literary figures, including Abbie Mitchell, Will Marion Cook, and prominent female composer Florence Price (1887-1953). Bonds composed her first work, Marquette Street Blues, at the age of five. In addition to taking piano lessons, she took composition lessons from Florence Price and William Dawson (1899-1990) before going to Northwestern University, a traditionally “white” college.

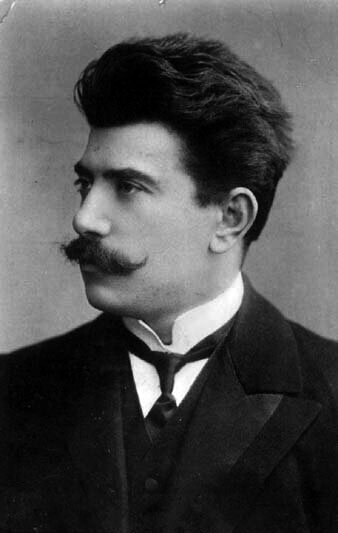

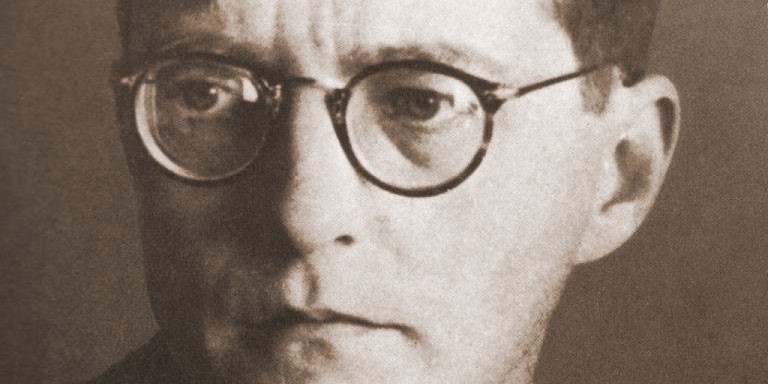

Florence Price (1887-1953)

Bonds completed both bachelor’s and master’s degrees in music at Northwestern University. During her studies, her song Sea Ghost won the Wanamaker Prize’s vocal category (1932). Also skilled as a professional pianist, she was the first African American woman to perform as a soloist with a major American orchestra. In 1933, she served as a solo pianist with the Chicago Symphony orchestra, playing John Alden Carpenter’s Concertino for piano and orchestra. In 1934, she performed Price’s Piano Concerto in D minor with the Women’s Symphony Orchestra. The same year, she finished her master’s degree at Northwestern University.

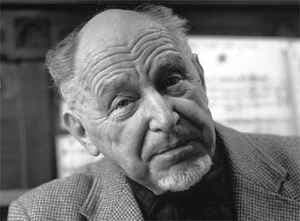

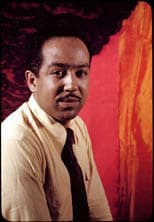

Langston Hughes © Carl Van Vechten / Carl Van Vechten Trust / Beinecke Library, Yale

In 1939, Bonds received a scholarship studying composition with Roy Harris (1898-1979) at the Julliard School of Music. She moved to New York, living in the historically black neighborhood of Harlem. She met her husband, Lawrence Richardson, through Langston Hughes. Langston Hughes (1902-1967), a prominent poet and a leading figure of the Harlem Renaissance, inspired Margaret Bonds in many ways. During her years studying at Northwestern University, Margaret Bonds experienced her first prolonged racism. She found great comfort in Langston Hughes’ signature poem, The Negro Speaks of Rivers. Margaret Bonds discovered more of his works and became more aware of her black heritage. They finally met in person in 1936, and they became lifelong friends and collaborators. According to Bonds’ daughter, Hughes was such a part of the family that he usually stayed at their house during Thanksgiving and Christmas. Soon after their first meeting in 1936, Margaret Bonds began to set his poems into music, including The Negro Speaks of Rivers.

Margaret Bonds devoted herself to elevating African American music and art. By blending the idiomatic musical language of spirituals and work songs, and the increasingly sophisticated vocabulary of jazz with the conventions of the western classical traditions, Bonds sought to re-establish African American culture and art as something complex, beautiful, something essential to the American identity. The collaborations between Langston Hughes and Margaret Bonds include numbers of vocal and choral works and plays.

Ballad of the Brown King

During the Civil Rights Movement, Margaret Bonds and Langston Hughes continued to collaborate and emphasize African American culture and values. She composed two significant works dedicated to Martin Luther King Jr., and one of them is the Ballad of the Brown King, which remained one of the most popular and frequently performed pieces of their collaboration. Inspired by the Civil Rights movement, this work was a Christmas cantata in honor of the African king, Balthazar. Premiered in New York in 1954, Bonds extended this short version to an orchestral version with nine movements, and it was performed in 1960 by Westminster Choir. The movements are all related in terms of keys and theme. Their musical styles continue to display Bonds’ trademark of utilizing European compositional technique with African American vernacular music. The 9-movements exhibit a variety of African American musical styles. It ranges from the traditional four-part hymn gospel, spirituals to calypso. Mary had a Little Baby, the fourth movement of the work, became one of the most famous pieces of the Ballad.

Troubled Water

For instrumental works, the majority of them are arrangements of spirituals. Bonds arranged over 50 spirituals into her compositions, and they often feature active and independent lines with expanded and rich harmonies. Troubled Water is perhaps the only published work for solo piano. The last movement of a three-movement Spiritual Suite, Troubled Water, is based on the spiritual Wade in the Water, and the title is probably inspired by its lyrics, “God’s gonna trouble the water.” Essentially a theme and variation, the contrapuntal technique and the overlapping “call and response” pattern once again represent Bonds’ blending of the classical western tradition and African American musical idioms, respectively. Idioms such as syncopation and jazz harmonies are found throughout the entire piece. This piece is full of excitement and drama with a triumphant ending that gets a strong audience response.

Margaret Bonds: Troubled Water

Due to its popularity, Bonds also rearranged Troubled Water for cello and piano, and symphony orchestra.

After Langston Hughes died in 1967, Margaret Bonds left New York and moved alone to Los Angeles. Although she continued to work diligently and kept bringing Langston Hughes’ works to the public, depression and alcoholism continued to affect her life. Sadly, when she passed away, many of her letters, music, and manuscripts were discovered in the dumpster by her house. While some of them are collected and stored in libraries’ archives, most of her work remains unpublished and unheard. The scope of her work and influence is yet to be fully known.