It's all about the classical music composers and their works from the last 400 years and much more about music. Hier erfahren Sie alles über die klassischen Komponisten und ihre Meisterwerke der letzten vierhundert Jahre und vieles mehr über Klassische Musik.

Total Pageviews

Sunday, January 14, 2024

Bert Kaempfert - Wonderland By Night (1960) 4K

The World We Knew (Over And Over)

Saturday, January 13, 2024

Glenn Miller - Chattanooga Choo Choo - Sun Valley Serenade (1941) HQ

THE LAST WALTZ - (ENGELBERT HUMPERDINCK / Lyrics)

Let’s meet in the Rat hole! Franz Liszt and Marie d’Agoult

by Georg Predota

“She was beautiful, very beautiful, a Lorelei: slender, of lofty bearing, enchantingly graceful and yet dignified in her movements, her head proudly raised, with an abundance of fair tresses, which waved over her shoulders like molten gold, a regular, classic profile, which stood in strange and interesting contrast with the modern breath of dreaminess and melancholy that was spread over her countenance; these were the general features which rendered it impossible to overlook her in the salon, the concert-room, or the opera-house, and these were enhanced by the choicest toilets, the elegance of which was surpassed by few, even in the salons of the Faubourg St. Germain.

Portrait of Marie d’Agoult by Henri Lehmann, 1843

That fantastic dreams were hidden behind the purity of her profile, and passion, burning passion, under the soft melancholy of her expression, was known to but a few, at the time that her connection with the young artist began.” The lady in question — described by the early Liszt biographer Lina Ramann — was none other than Marie Catherine Sophie d’Agoult. Born Marie Flavigy in Frankurt am Main, she was sent to Paris at the age of sixteen. Once she had finished her education at the Sacré Coeur, and after a torrid affair with the poet Alfred de Vigny, she married the Comte Charles d’Agoult in 1827. He was fifteen years her senior, an ill-mannered and hardly functioning war veteran, and love was simply not part of the equation. They did have two children, but by and large, they conducted an open marriage. That left Marie — who described herself as six inches of snow covering twenty feet of lava — with plenty of time to enjoy the sparkling gaiety of the salon.

In early 1833, the Marquise Le Vayer invited Marie to sing in a women’s choir. The guest of honor was Franz Liszt. In her memoirs, Marie details this first encounter: “I use apparition because I can find no other word to describe the sensation aroused in me by the most extraordinary person I had ever seen. He was tall and extremely thin. His face was pale and his large sea-green eyes shone like a wave when the sunlight catches it. His expression bore the marks of suffering. He moved indecisively and seemed to glide across the room in a distraught way, like a phantom for whom the hour when it must return to the darkness is about to sound. Franz spoke with vivacity and with an originality that awoke a whole world slumbering in me. The voice of the young enchanter opened out before me a whole infinity, into which my thoughts were plunged and lost. Between us there was something at once very young and very serious, at once very profound and very serious.”

Marie was six years older than the young enchanter, and by the early summer of 1833 their affair was in full bloom. Liszt visited her in Croissy, and Marie came to Paris where they secretly met in a small apartment affectionately referred to as the “rat hole.” The chemistry was unmistakable, and by May 1833 she wrote, “Sometimes I love you foolishly, and in these moments I comprehend only that I could never be so absorbing a thought for you as you are for me.”

Franz Liszt, 1847

Liszt’s declaration of love was not far behind, and burning with desire he writes: “How ardent, how glowing on my lips is your last kiss! Marie, Marie, let me repeat that name a thousand times. It lives within me, burns me and threatens to consume me. I am not writing you; I am with you. Oh for an eternity in your arms. There is heaven and hell, and everything else, inside you, yes, inside you. Let me be wild and crazy. I am beyond help.” Concordantly, Liszt introduced himself to the public as a mature and original composer with his poetic Harmonies poétiques et religieuses and a set of three Apparitions. However, these early days of courtship did not run entirely smoothly. Some of the love letters he had written to Adèle de Laprunarède following their winter tryst in the Savoy came into Marie’s hands and sparked a violent jealous row. Although he pleaded with her to accept the letters as immature follies, Marie never really forgave him. In addition, Marie’s six-year-old daughter Louise fell ill, and within a couple of days died from massive inflammation of the brain.

It is unclear whether Marie considered this tragedy a punishment for her illicit affair with Franz, but in her state of depression and despair, in which she contemplated suicide, she refused to answer his calls or his letters. After nearly six months of being unable to see Marie, Franz wrote her a letter announcing his intention of leaving France, and expressing his desire to see her one last time. Marie relented and travelled to Paris for an emotional reunion in March of 1835. Blandine, their first daughter, was born nine months later.

Sweetest Harmony

For me personally, it’s such an uplifting thought that countless people, particularly in the arts and music, are trying to promote peace and harmony through shared performances. Take for example, the “Harmony of Nations Baroque Orchestra,” a period-instrument group of young musicians from all over Europe. The 20-founding members are from 14 different Nations, including England, France, Germany, Greece, Hungary, Italy, Norway, Poland, Portugal, Spain, Sweden, Switzerland, and Wales.

Harmony of Nations Orchestra

They speak different languages and celebrate an incredible diversity of cultural heritage. Many have lived and studied in countries other than their own, but what unites them is a common musical heritage and a desire for social harmony. And it is easy to hear the delicious result in their delight in producing the sweetest harmonies.

In 1695, the composer Georg Muffat wrote, “Weapons of war and their use are something I am unable to engage with. I busy my time with notes, strings, and sounds. I work in the cause of harmony, mixing the sounds of France, Germany, and Italy and attempting thus to prevent wars and to serve the cause of peace among nations and their striving for peace.’’

Georg Muffat

Muffat’s words are as relevant today as they were over 300 years ago. He was among the most cosmopolitan composers of the seventeenth century, growing up in the Duchy of Savoy and Alsace, regions subject to political ambitions of France and the Holy Roman Empire.

His “Florilegium Secondum” (Second Garland of Flowers) of 1698 contains dances in what he calls “a more sweet harmony.” Here, the composer takes us on a musical tour of European national musical styles and conventions, all the way from Spain to Holland, England, Italy, and France.

The Austrian composer, violinist, and silvologist—a biological scientist studying the natural ecosystems of forests and woodlands, Carl Ditters von Dittersdorf was born in 1739. He was a prolific and versatile contemporary of Haydn and Mozart, and he already knew that engagement and dialogue were the most important elements in establishing harmony among nations.

Portrait of Carl Ditters von Dittersdorf by Heinrich Eduard Wintter

National musical differences have long stimulated the creative interest of artists. For his “Symphony in the Style of Five Nations” Dittersdorf presents a fairly predictable line-up. We find the Germans, the Italians, the French, the English and the Turks. But Dittersdorf adds a little twist. He actually composes parodies of musical tastes and perhaps characters.

The Germans get things started, and all with a good bit of earnestness and determination. The Italians are portrayed as bombastic, the French as courtly and old-fashioned, the English as musically naïve, and the Turks with vigorous rhythmic intensity. The point of parody is not to insult but to invite dialogue about differences. Stand-up comedians do this all the time. In the end, Dittersdorf brings everybody together in a Finale that represents a kind of musical equivalent of the European Union.

If you ask me personally, the two biggest factors in achieving sweet harmony among nations are education and enlightenment. The sheer amount of misinformation floating around us today is pretty staggering. Education won’t give you the answers, but it will teach you how to ask meaningful and enlightened questions about any subject.

Orchestra of the Age of Enlightenment

Taking a long and hard look at what constituted an “orchestra” led to the formation of the OAE, the Orchestra of the Age of Enlightenment, in 1986. They threw out the rulebook on conducting and specializing in repertoires of a particular area. They picked up period instruments and kept questioning, adapting, and inventing.

The real challenge was to turn eccentric idealists into a coherent group. So, they agreed on how to organise and remain experimentalists. They welcomed new talents and kept on exploring performance formats, rehearsal approaches, and musical techniques. If only we could get politicians to approach their responsibilities in such an enlightened manner.

If you believe that music cannot bring people together, think again. Just ask Maestro Paavo Järvi and the Deutsche Kammerphilharmonie Bremen. The orchestra is considered at the forefront of interpreting the Classical and Romantic repertoire. Committed to colourful and transparent performances, the ensemble has captivated audiences around the world.

Maestro Paavo Järvi

But here is the unusual part. All 41 members of the orchestra enjoy brilliant and highly successful solo careers. From the very beginning, the musicians wanted to break new musical grounds and make key decisions on all musical issues, including performance repertory, via a democratic process. Every member of the orchestra is also a vested shareholder, and they are jointly responsible for the economic success of the business as a whole.

Collaborating with the Grammy Award-winning conductor Paavo Järvi, the result has been called sensational. The orchestra is responsive, virtuosic and alert, and Järvi’s readings are energetic, often thrilling and thoughtful, yet also driving and objective. Based on mutual respect, artistic chemistry and a profound and intuitive understanding between conductor and orchestra, isn’t it amazing that so many highly skilled individuals come together to produce the sweetest harmony in complete agreement—after much deliberation and discussion, I am sure.

Classical music is not locked-up in history but as relevant as ever because it deals with fundamental human issues. And harmony amongst nations and people is an eternal, and sometimes it seems hopeless quest. But that doesn’t mean that musicians, artists, and thinkers aren’t continuing to promote peace and harmony.

Daniel Barenboim © Peter Adamik

The pianist and conductor Daniel Barenboim is simultaneously a citizen of Argentina, Israel, Palestine, and Spain. In 1999, he teamed up with the Palestinian American academic, literary critic, and political activist Edward Said. Together they established the West-Eastern Divan orchestra as an attempt to promote understanding between Israelis and Palestinians. Bringing together young classical musicians from Israel, the Palestinian territories, and Arab countries to study and perform, this initiative advocates a peaceful and fair solution to the Arab-Israeli conflict.

Barenboim stated, “The Divan is not a love story, nor a peace story. It has very flatteringly been described as a project for peace. It isn’t. It’s not going to bring peace, whether you play well or not so well. The Divan was conceived as a project against ignorance… I am not trying to convert members of the Divan to a certain point of view, but create a platform where the two sides can disagree and not resort to knives.”

Well, Barenboim was correct, as the West-Eastern Divan Orchestra has certainly not brought peace to the region. In fact, Barenboim is now being viciously attacked for trying to advocate peace, harmony, and understanding. As elsewhere, however, the voices of reason, enlightenment, and knowledge will never be silenced when it comes to art and music.

Vivaldi’s Four Seasons and the Impact of Climate Change

by Hermione Lai , Interlude

The Four Seasons, the fabulous collection of four violin concerti by Antonio Vivaldi have topped the Classical Music charts for decades on end. It has become part of modern culture, and the music is reshaped and arranged into different musical styles and adapted for solo instruments other than violin.

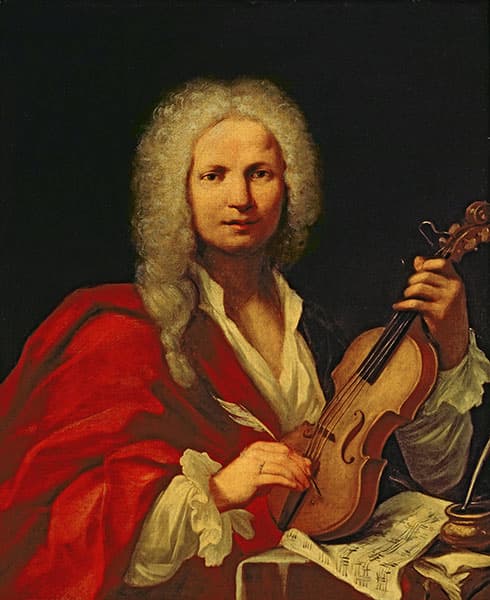

Portrait of Antonio Vivaldi

Vivaldi gave each concerto the title of a specific season, and his music imitates the sounds of barking dogs, warbling birds, the icy paths across frozen water, and even the blazing temperatures of summer. It’s a delightful and charming nature painting in music. The music was composed roughly 300 years ago, but times are changing, and so is the climate.

Simone Candotto, the solo trombonist of the Hamburg Elbphilharmonie Orchestra, was born in a town near Venice, Vivaldi’s place of work. And we all know that Venice is gradually sinking into the sea because of the consequences of climate change. As such, Candotto decided to let people hear the consequences of climate change by re-composing The Four Seasons using climate data.

Simone Candotto

He engaged a team of software developers and music arrangers, and with the aid of a specific algorithm, he modified the source material to reflect the consequences of climate change. Much of that algorithm is based on 300 years of climate data, incorporating the increase in greenhouse gas carbon dioxide over the past centuries to the present day.

You can hear these changes very clearly in the music, as the summer motif already sneaks into the score in the spring. The seasons are clearly changing, and the rise of the global CO2 curve results in the notes becoming longer. Candotto explains, “It’s a big deal because I think it has an impact. But above all, there are the themes from the other seasons that come in so imperceptibly. That gives the impression that things are no longer the same as they used to be.”

Since there are 15 percent fewer birds chirping in the trees than in the time of Vivaldi, the algorithm uses 15 percent less of the bird motifs to indicate the extinction of species. Extreme weather is sharply increasing, and Vivaldi arrives in the present.

You can hear the solo violin continuing to play part of the Vivaldi “Winter” concerto while the orchestra sinks into dissonant lethargy. It’s almost like a metaphor, with people continuing to live as before while nature sinks into chaos due to man-made climate change.

The idea of using climate data to recompose Vivaldi’s “The Four Seasons” has also been taken up by composer Hugh Crosthwaite and Monash University’s Climate Change Communication Research Hub. This creation looks to portray a future where the world has failed to act on global warming.

This reworking also features AI algorithms based on climate predictions for the year 2050. It is a musical design system “that combines music theory with computer modelling to algorithmically generate countless local variations of the Vivaldi composition.” That is, it can model climate predictions for every location on the planet.

Looking at climate data, the algorithm alters the musical score to account for predicted changes in rainfall, biodiversity, sea-level rise, and extreme weather events for the location of performance. In some locations, storms will be more intense, the sea level will be dangerously rising, and wildlife will disappear.

There is no doubt that climate change is unravelling our seasons, and Spanish music director Hache Costa has adopted Vivaldi’s most famous work to reflect the grim reality of global warming. “If someone were to compose The Four Seasons from an absolutely realistic perspective,” the composer writes, “the music would be much more aggressive and grittier.”

Costa projects the effects of global warming by adding prominence and drama to the summer concerto while shortening the other three. This re-composition is accompanied by projected images of wildfires and other effects of climate change, including drought. As Costa explained, “I would love the audience to feel really bothered at some point by becoming truly aware of what is happening.”

Max Richter

Award-winning composer and pianist Max Richter is not attempting to shock his audience, but he is actually advocating dialogue instead. Classically trained, Richter graduated in composition from the Royal Academy of Music and studied with the legendary Italian composer Luciano Berio. He loved the Vivaldi original as a child, but hearing the music abused for various reasons and causes, “it becomes an irritant.”

So, he decided to recompose the music, and his “New Four Seasons” weaves and loops the music to become a conversation between instruments and also a dialogue between the two composers. “There are sections where I’ve left Vivaldi alone,” he explains, “and other bits where there is basically only a homeopathic dose of Vivaldi in completely new music.” When it comes to climate change, we need a global dialogue with everybody pulling at the same string, and hopefully, Vivaldi can bring us all together.

Thursday, January 11, 2024

Barenboim - "El amor brujo" (Danza ritual del fuego) Falla

FILIPINO CLASSIC SONGS - Winning Piece By Harvard Westlake Choir

Wednesday, January 10, 2024

Frank Sinatra - The World We Knew (1967)

Tuesday, January 9, 2024

Aaron Copland - his music and his life

Aaron Copland managed the difficult feat of becoming a popular classical composer while retaining the respect of critics and the ‘serious musical establishment'.

Born in a humble street in Brooklyn, the son of Lithuanian immigrants, Copland is generally regarded as the first indisputably great American composer. The piano came easily to him and, after he’d graduated from the local high school, he had lessons in harmony and counterpoint from the eminent (though conservative) teacher and composer Rubin Goldmark. His first published piece, The Cat and the Mouse, appeared in 1920.

He was able to scrape together enough to go to Paris to study with the doyenne of European teachers, Nadia Boulanger. Here, during his four years at the New School for Americans at Fontainebleau (1921-25), Copland was introduced to an enormous range of musical influences, all of which he was encouraged to absorb: jazz, the neo-classicism of Stravinsky and the whimsicality of Les Six made a particularly strong impression on him and colour the first period of his mature compositions. With a thorough grounding in composition and orchestration under his belt, he returned to America where he became involved in a wide range of musical activities, working as a pianist in a hotel, as a lecturer and as an organiser of various musical societies, as well as composing.

Conductor, publisher and patron of music Serge Koussevitzky became an influential champion of his music throughout his tenure as conductor of the Boston Symphony Orchestra, an incalculable boost to Copland’s growing reputation. Between 1930 and 1936 he entered a phase of experimental and dissonant writing (Variations and the Piano Sonata, for instance, are difficult works) before discovering the power of American folk idioms. Here his music is as essentially American as Mussorgky’s or Stravinsky’s is Russian – El Salón México, the ballets Billy the Kid, Rodeo and Appalachian Spring are as American as apple pie. His Lincoln Portrait, using texts from Lincoln’s speeches and letters, has been performed (for better or worse, but generally worse) by world leaders. His patriotic Fanfare for the Common Man (1942) has been used for the opening of every type of formal ceremony. Some of Copland’s film music (The Red Pony, for example, Our Town and Of Mice and Men) is among the most distinguished ever written (he won an Oscar in 1950 for the score of The Heiress). In a nutshell, Copland managed the difficult feat of becoming a popular classical composer while retaining the respect of critics and the ‘serious musical establishment’. In his later works, Copland reverted to serial techniques, writing in a far less approachable, more austere manner.

Whatever one thinks of his virtually unknown middle- and late-period music, Copland has to be admired for his steadfast independence and unwillingness to court popularity for its own sake.

YESTERDAY WHEN I WAS YOUNG - Shirley Bassey (Lyrics)

Franz Lehar- "Gold und Silber",Walzer (Springtime In Vienna 98)

Iosif Ivanovici - Waves of the Danube

Sinead O'Connor died of 'natural causes', UK coroner rules

AT A GLANCE

The Grammy award-winning singer, best known for her 1990 cover of "Nothing Compares 2 U", was found unresponsive at her south London home last July. She was 56.

LONDON (AFP) - Irish musician Sinead O'Connor died last year of "natural causes", a London coroner announced Tuesday.

The Grammy award-winning singer, best known for her 1990 cover of "Nothing Compares 2 U", was found unresponsive at her south London home last July. She was 56.

London police said at the time that officers were not treating it as suspicious as an autopsy was carried out to determine the cause of her death.

A short statement by Southwark Coroner's Court in south London said: "This is to confirm that Ms O'Connor died of natural causes. The coroner has therefore ceased their involvement in her death."

O'Connor's death prompted an outpouring of sympathy from her legions of fans including other musicians and celebrities around the world, particularly in her homeland of Ireland.

Hundreds lined the route of her cortege in Bray, the Irish town 20 kilometres (13 miles) south of Dublin that she called home for 15 years, on the day of her funeral last August.

The willingness of the musician, who rose to international fame in the 1990s, to criticise the Catholic Church in particular saw her vilified by some and praised as a trailblazer by others.

O'Connor's agents revealed she had been completing a new album and planning a tour as well as a movie based on her autobiography "Rememberings" before she died.

The musician had also spoken publicly about her mental health, telling the US television host Oprah Winfrey in 2007 that she struggled with thoughts of suicide and had been diagnosed with bipolar disorder.

More recently she had shunned the limelight, in particular following the death of her son Shane from suicide in 2022 aged 17.