by

It may be two years or twenty since you last touched a piano, but however long the absence, taking the decision to return to playing is exciting, challenging and just a little trepidatious.

Stick with the familiar and play the music you learnt before

Stick with the familiar and play the music you learnt before

To get back in to the habit of playing, start by returning to music you have previously learnt. You may be surprised at how much remains in the fingers and brain, and while facility, nimbleness and technique may be rusty, it shouldn’t take too long to find the music flowing again, especially if you learnt and practised it carefully in the past.

Take time to warm up

You may like to play scales or exercises to warm up, but simple yoga or Pilates-style exercises, done away from the piano, can be very helpful in warming up fingers and arms and getting the blood flowing. This kind of warm up can also be a useful head-clearing exercise to help you focus when you go to the piano.

You don’t have to play scales or exercises!

Some people swear by scales, arpeggios and technical exercises while others run a mile from them. As a returner, you are under no obligation to play scales or exercises. While they may be helpful in improving finger dexterity and velocity, many exercises can be tedious and repetitive. Instead try and create exercises from the music you are playing – it will be far more useful and, importantly, relevant.

Invest in a decent instrument

If you are serious about returning to the piano, a good instrument is essential. It needn’t be an acoustic piano; there are many very high-quality digital instruments to choose from. Select one with a full-size keyboard and properly weighted keys which imitate the action of a real piano. The benefits of a digital instrument are that you can adjust the volume and play with headphones so as not to disturb other members of your household or neighbours, and most digital instruments allow you to record yourself or connect to apps which provide accompaniments or a rhythm section which makes playing even more fun!

Posture is important

You’ve got a good instrument, now invest in a proper adjustable piano stool or bench. Good posture enables you to play better, avoid tiredness and injury.

Little and often

Your new-found enthusiasm for the piano may lead you to play for hours on end over the weekend but hardly at all during the week. Instead of a long practice session, aim for shorter periods at the piano, every day if possible, or at least 5 days out of 7. Routine and regularity of practice are important for progress.

Consider taking lessons

A teacher can be a valuable support, offering advice on technique, productive practising, repertoire, performance practice, and more. Choose carefully: the pupil-teacher relationship is a very special one and a good relationship will foster progress and musical development. Ask for recommendations from other people and take some trial lessons to find the right teacher for you.

Pianists at Finchcocks course

Go on a piano course

Piano courses are a great way to meet other like-minded people – and you’ll be surprised how many returners there are out there! Courses also offer the opportunity to study with different teachers, hear other people playing, get tips on practising, chat to other pianists, and discover repertoire. Many courses in the UK cater for students of all levels, including those at Finchcocks in Kent and Jackdaws in Somerset.

Join a piano club

If you fancy improving your performance skills in a supportive friendly environment, consider joining a piano club. You’ll meet other adult pianists, hear lots of different repertoire, have an opportunity to exchange ideas, and enjoy a social life connected to the piano. Piano clubs offer regular performance opportunities which can help build confidence and fluency in your playing.

Listen widely

Listening, both to CDs or via streaming or going to live concerts, is a great way to discover new repertoire or be inspired by hearing the music you’re learning played by master musicians.

Buy good-quality scores

Cheap, flimsy scores don’t last long and are often littered with editorial inconsistencies. If you’re serious about your music, invest in decent sheet music and where possible buy Urtext scores (e.g. Henle, Barenreiter or Weiner editions) which have useful commentaries, annotations, fingering suggestions and clear typesetting on good-quality paper.

Play the music you want to play

One of the most satisfying aspects of being an adult pianist is that you can choose what repertoire to play. Don’t let people tell you to play certain repertoire because “it’s good for you”! If you don’t enjoy the music, you won’t want to practice. As pianists we are spoilt for choice and there really is music out there to suit every taste.

Above all, enjoy the piano!

Later mythologized as a true Italian, Giuseppe Verdi was born on October 10, 1813 in Busseto as a French subject, which seems to have disturbed him enough to lead him to represent that he had in fact been born in 1814, in which year the Dukedom of Parma, to which Busseto belonged, became an independent Italian state. Throughout most of the 19th century, Italy was not a political entity, but rather a cultural idea, where everyone, whether in Milano, Venice, Genoa, in the Piedmont and in the many other cities and states, could live as a member of an ancient, noble and respectable cultural community, irrespective of borders, customs and tariffs. A political union had been impossible, since the major European powers — Germany, Spain, France and Austria, as well as the Papal States — controlled the various Italian regions. The 19th century saw a re-awakening, the ‘risorgimento’ as it would later be called — a cry for political unity and independence, whose most outspoken representative was the writer Vittorio Alfieri, whom Verdi very much admired. Alfieri conceived Italian nationalism as a spiritual/political idea of liberation and freedom, a concept which became the focus of various political movements in the following years.

Later mythologized as a true Italian, Giuseppe Verdi was born on October 10, 1813 in Busseto as a French subject, which seems to have disturbed him enough to lead him to represent that he had in fact been born in 1814, in which year the Dukedom of Parma, to which Busseto belonged, became an independent Italian state. Throughout most of the 19th century, Italy was not a political entity, but rather a cultural idea, where everyone, whether in Milano, Venice, Genoa, in the Piedmont and in the many other cities and states, could live as a member of an ancient, noble and respectable cultural community, irrespective of borders, customs and tariffs. A political union had been impossible, since the major European powers — Germany, Spain, France and Austria, as well as the Papal States — controlled the various Italian regions. The 19th century saw a re-awakening, the ‘risorgimento’ as it would later be called — a cry for political unity and independence, whose most outspoken representative was the writer Vittorio Alfieri, whom Verdi very much admired. Alfieri conceived Italian nationalism as a spiritual/political idea of liberation and freedom, a concept which became the focus of various political movements in the following years. In Italy, even language divided the different Italian regions, in which everyone spoke the specific dialect of the district — Italian as such was used only as a written language and was unfamiliar to most. The only languages everyone did understand, were those of music and poetry, such as that of Ludovico Ariosto and Torquato Tasso. Music and opera made it possible for every Italian to be part of this nation of culture, a unity of the people. Music, as the true expression of feelings, of the heart, of passions, could therefore be considered the true language of the people. Already in earlier centuries, Italians knew that they were a European musical power, for example with Cherubini in Paris and Spontini in Berlin, and that Vienna, with

In Italy, even language divided the different Italian regions, in which everyone spoke the specific dialect of the district — Italian as such was used only as a written language and was unfamiliar to most. The only languages everyone did understand, were those of music and poetry, such as that of Ludovico Ariosto and Torquato Tasso. Music and opera made it possible for every Italian to be part of this nation of culture, a unity of the people. Music, as the true expression of feelings, of the heart, of passions, could therefore be considered the true language of the people. Already in earlier centuries, Italians knew that they were a European musical power, for example with Cherubini in Paris and Spontini in Berlin, and that Vienna, with  In 1842, again in Milano, Verdi achieved real fame with his opera, ‘Nabucco’, which also saw tremendous success in Vienna in 1843. All of the famous salons in Milano now became open to him, in particular the salon of Clarina and Andrea Maffai (descendants of the Italian/German aristocracy with familial connections to Munich and Salzburg), who introduced Verdi to ‘world literature’, in particular the works of Klopstock, Schlegel,

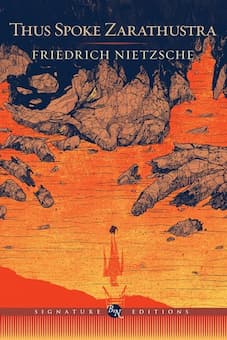

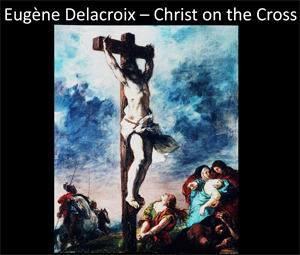

In 1842, again in Milano, Verdi achieved real fame with his opera, ‘Nabucco’, which also saw tremendous success in Vienna in 1843. All of the famous salons in Milano now became open to him, in particular the salon of Clarina and Andrea Maffai (descendants of the Italian/German aristocracy with familial connections to Munich and Salzburg), who introduced Verdi to ‘world literature’, in particular the works of Klopstock, Schlegel,  As I have mentioned before, Verdi was very familiar with the ‘classical’ works of Shakespeare, the ‘romantic’ works of Victor Hugo, Lord Byron and Alexandre Dumas and based many of his operas on their works. Interestingly, Shakespeare had been rediscovered by the French Romantic painters and writers in the 19th century, who saw him as a revolutionary playwright. In his plays, Shakespeare had never adhered to, and had broken, with the classical French dictum of the ‘unity of time, action and space’, where all stage performance had to adhere to the 24-hour rule, i.e. that all the action on stage had to be started and completed within a 24 hour day. In opera, one such example of the rule is Mozart’s ‘Abduction from the Seraglio’, where the action starts with the abduction and ends with the resolution and celebratory meal 24 hours later. Another example is

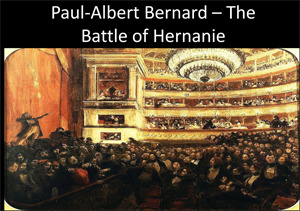

As I have mentioned before, Verdi was very familiar with the ‘classical’ works of Shakespeare, the ‘romantic’ works of Victor Hugo, Lord Byron and Alexandre Dumas and based many of his operas on their works. Interestingly, Shakespeare had been rediscovered by the French Romantic painters and writers in the 19th century, who saw him as a revolutionary playwright. In his plays, Shakespeare had never adhered to, and had broken, with the classical French dictum of the ‘unity of time, action and space’, where all stage performance had to adhere to the 24-hour rule, i.e. that all the action on stage had to be started and completed within a 24 hour day. In opera, one such example of the rule is Mozart’s ‘Abduction from the Seraglio’, where the action starts with the abduction and ends with the resolution and celebratory meal 24 hours later. Another example is  Verdi used Victor Hugo’s play ‘Hernani’ as the basis for his opera by the same name. In 1830, Hugo’s ‘Hernani’ had its first Paris performance as the first Romantic play, and had met with fierce opposition from the French audience, although valiantly defended by Hector Berlioz, Théophile Gautier and many of the French Romantic writers and painters. Hugo had broken all of the classical rules — the locale and action in his play changed often and they exceeded the 24 hour day. Composed in 1844, Verdi insisted that his opera libretto follow Hugo’s play as closely as possible, and so, in Act I, the action is situated in the mountains of Aragon; in Act II, in Don Ruy Gomez Castle; in Act III, in Charlemagne’s tomb in Aachen; and in act IV, back to Spain, in Saragossa. The opera also shows the young Verdi honing his operatic skills in creating dramatic tension (three men pay court to one woman), with the conspiracy scene, its evocative orchestral coloring, and in general, the lyrical fervor of his arias (‘Ernani… Ernani involami’; ‘Vieni meco, sol di rose’, etc.), setting the new standards for Romantic operas — Italian style.

Verdi used Victor Hugo’s play ‘Hernani’ as the basis for his opera by the same name. In 1830, Hugo’s ‘Hernani’ had its first Paris performance as the first Romantic play, and had met with fierce opposition from the French audience, although valiantly defended by Hector Berlioz, Théophile Gautier and many of the French Romantic writers and painters. Hugo had broken all of the classical rules — the locale and action in his play changed often and they exceeded the 24 hour day. Composed in 1844, Verdi insisted that his opera libretto follow Hugo’s play as closely as possible, and so, in Act I, the action is situated in the mountains of Aragon; in Act II, in Don Ruy Gomez Castle; in Act III, in Charlemagne’s tomb in Aachen; and in act IV, back to Spain, in Saragossa. The opera also shows the young Verdi honing his operatic skills in creating dramatic tension (three men pay court to one woman), with the conspiracy scene, its evocative orchestral coloring, and in general, the lyrical fervor of his arias (‘Ernani… Ernani involami’; ‘Vieni meco, sol di rose’, etc.), setting the new standards for Romantic operas — Italian style.