by

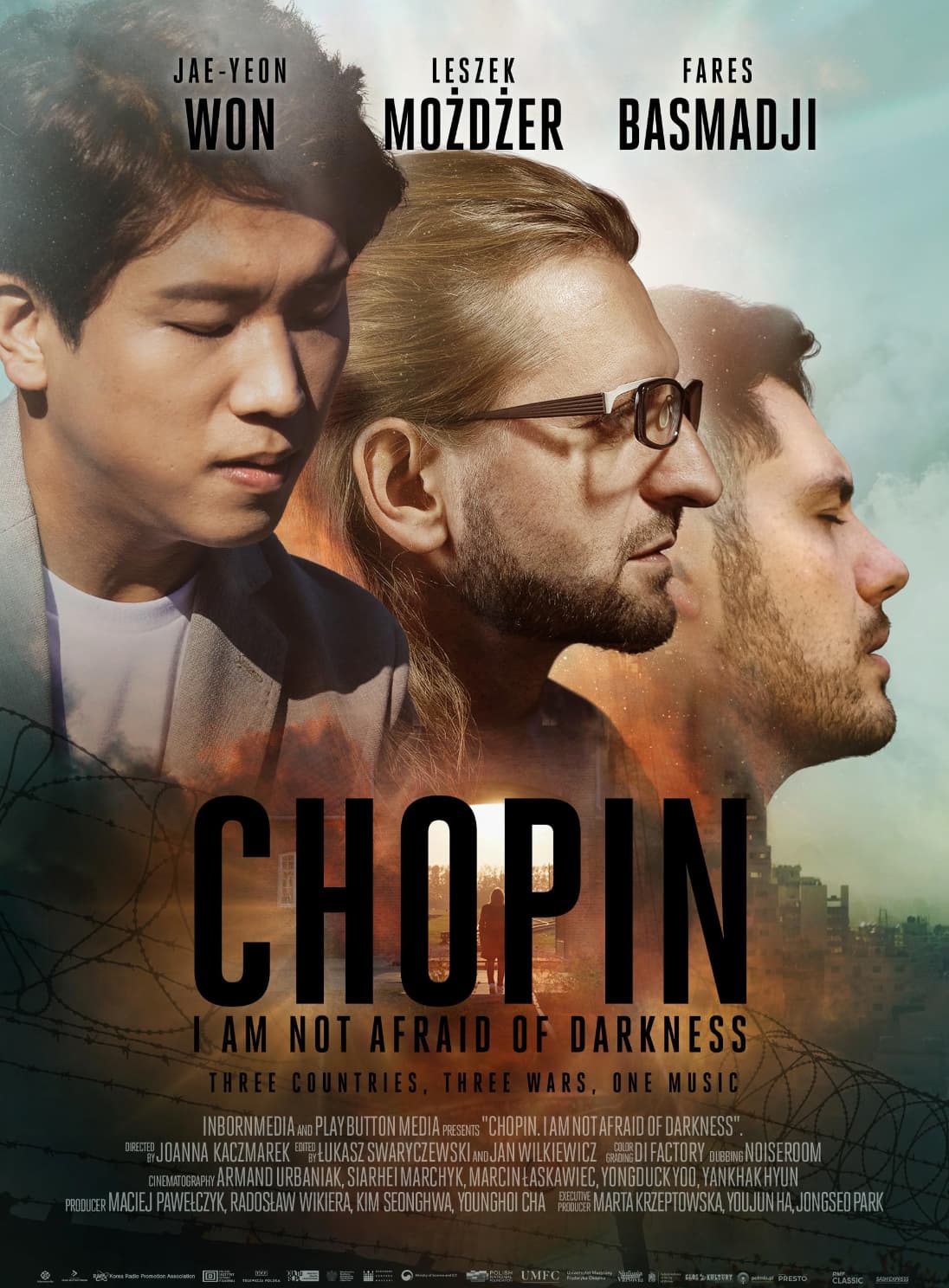

A very special documentary entitled Chopin: I am Not Afraid of Darkness illustrates the power of music to transform people of all cultures. The film received an award at the 59th Golden Prague International Festival and is being screened worldwide at film festivals around the world.

I had a chance to have an in-depth conversation with the producer and director of Chopin: I am Not Afraid of Darkness, Maciej Pawelczyk of Inbornmedia, a TV production company. They produce more than 100 hours of TV content and independent documentaries per year and sell to companies in the UK, Europe, Asia, and the U.S.

We’ll begin by setting the tone with Chopin‘s Prelude in A Minor, Op. 28, No. 2.

Chopin: I am Not Afraid of Darkness © IMDb

What a moving and provocative film! Tell us how you chose the three settings and the three musicians to feature.

Thank you, Janet. As a creative film producer, I feel flattered. We sought locations not only symbolic but also steeped in the sorrows and shadows of history’s darkest chapters, which would resonate powerfully with Chopin’s music within our film. We aimed to juxtapose the evil aura of these places with the sublime beauty of Chopin’s compositions and to explore the transformative potential of music. Since it is a Polish-Korean co-production, the film naturally led us to locations in Poland and South Korea.

In Poland, setting the bar very high, we chose the Nazi German Death Camp Auschwitz. This site arguably represents the bleakest moment in human history and the epicenter of mass atrocities during World War II. Heavy with unspeakable horrors, it evokes intense emotions. We chose Leszek Możdżer, a celebrated Polish jazz pianist whose unique persona and metaphysical engagement with music promised to counterbalance the oppressive and sinister atmosphere of Auschwitz, anticipating an extraordinary, hopeful musical experience.

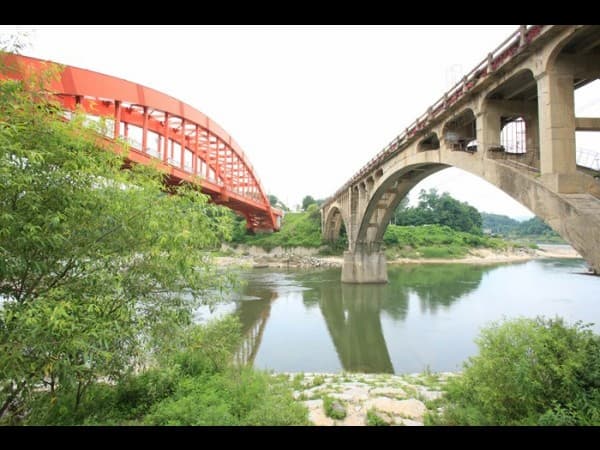

Seungilgyo Bridge

We considered what story to unfold in South Korea and chose the Seungilgyo Bridge as our stage, at the border alongside the authoritarian regime of North Korea. The construction of the remarkable site began under North Korean control but was completed by the South. Our Korean co-producers from Play Button Media brought Jae-Yeon Won on board, a distinguished South Korean classical pianist, who performed on the bridge that symbolizes a nation’s torn past and its resilient spirit.

Finally, our third protagonist represents multiple cultural narratives. Fares Marek Basmadji, born in Aleppo, Syria, to a Syrian father and a Polish mother, later becoming a resident of Great Britain, personifies this synthesis. Given the ongoing conflict in Aleppo, we arranged for his appearance to be in Lebanon, a refuge for countless Syrian refugees. Beirut is close to the port where a devastating explosion recently occurred. The location is a poignant reminder of the enduring human spirit amidst chaos and despair.

As you can see, each musician and each setting were meticulously chosen to reflect our film’s core theme: the enduring power of music to heal and uplift, even amid history’s most painful scars.

One of the prominent pieces, Etude Op. 10 No. 3 in E Major called the “Tristesse,” is slow and cantabile with a stunning melody—at times optimistic, tender, and nostalgic. I think the poetic nature of the piece allows the audience to be contemplative.

The result exceeded my expectations. This project was not merely about organizing concerts; it explored how spaces imbued with powerful histories interact and reverberate through music. The juxtaposition of Chopin’s passionate music with the intense energy of the chosen locations created an almost tangible atmosphere, deeply resonating with the audience.

It must have presented tremendous logistical concerns.

Navigating the concerts in Korea and Lebanon posed challenges, but the most daunting was playing a concert in Auschwitz, Poland. I was quite terrified. How would it play out? There, the air is heavy with the memories of over a million souls lost, making it the most earth-shattering cemetery in the world. Engaging with an audience so deeply intertwined with these past atrocities required delicacy and reverence. One of the attendees, Elżbieta Ficowska, was saved due to the initiative and bravery of Irena Sendler, who hid the six-month-old child in a wooden box, placed her on a wagon full of bricks, and transported her from the Jewish ghetto to safety. This, of course, brought enormous depth to our film.

In Beirut, the presence of Syrian audience members, including those who had fled the devastation of their homeland, lent an additional layer of complexity. For Fares, the pianist, performing there was not only an artistic endeavor but also a personal journey into the heart of his country’s suffering. The proximity of the concert stage to the site of the recent port explosion added a raw, immediate context. I can’t forget a deeply touching moment when a woman, who was perched high above the concert looking down from a window, became visibly moved by the performance. The tears of onlookers and the silent grief of the city were palpable.

In Korea, the Seungilgyo Bridge represents a poignant symbol for the listeners. A listener reflected upon his grandfather who perished in the Korean War, the bridge symbolizing the huge toll of the conflict. For another attendee, a defector from North Korea, its spans signify the bittersweet embodiment of his journey from oppression to freedom. The bridge is a powerful metaphor for their experiences—not only a physical crossing but an emotional and historical one. It’s a poignant and daily reminder of a divided homeland, highlighting the stark contrast between the suffocating control of the regime and the liberating embrace of their new lives.

I witnessed a kaleidoscope of emotions during these concerts. The director, Joanna Kaczmarek, and I were able to capture this emotional tapestry on the screen. The synthesis of Chopin’s music with the intensity of the locations created an unforgettable journey—I still have tears in my eyes when I watch the final scene!

There’s a lovely image of the grand piano on an otherwise empty stage with empty seats behind it. We hear the Korean protagonist play the Chopin Concerto No. 1 in E minor Op. 11 with a group of string players. How did you decide how much of the individual performers’ histories to depict and their personal connection to the sites within the larger conflict of the actual locations?

Maciej Pawelczyk

Creating a harmonious balance posed a considerable challenge. We chose Polish jazz pianist Leszek Możdżer not because of any historical ties to the extermination camp but because of his captivating personality and metaphysical approach to music. His segment had to transcend conventional storytelling. The omnipresent shadow of Auschwitz, the factory of death, called for a weighty meditation on the battle between good and evil. Music here, we felt, needed to act as a cosmic and crushing force so deep that it would dominate the story.

Our Korean protagonist is from Paju, just 30 kilometers from the North Korean border. He passes by the barbed wire daily, and it stirs deep reactions in him. It’s a stark reminder of one of the world’s most oppressive regimes, where freedom of expression is perilously curtailed.

The most intimately woven narrative, however, emerged in the poignant tale of Fares, who was driven by two deeply significant motives. First, a desire to reconnect with his fellow Syrians displaced by the war, and second, by performing one final concert to bring closure to his musical journey.

As a documentary producer, when I see we’ve genuinely made an impact on the protagonists, I am gratified. This was the case here. Fares decided to wear a traditional Syrian costume. Once a source of shame, the garment symbolized his journey and transformation, his deeper understanding and empathy towards others, free from the shackles of prejudice and stereotypes. At the same time, we set Fares’ personal story against the backdrop of the Syrian war. The conflict has displaced millions of Syrians, who fled to Lebanon, a country beleaguered by a severe economic crisis. The interplay between Fares’ individual experience and the larger context revealed the goal of our film: to weave the personal narratives with the historical and social conflicts of the locations and to create a rich, multifaceted story.

You describe how one’s work “is never done” when playing music. As a musician, I know that musical interpretations are not only a reflection of the growth the musician has experienced up to the time of performance and the inspiration the musician feels in the moment but also in the resonance achieved in and from the audience. The actor describes this eloquently. How did you decide to depict the final scenes and the resonance with the three audiences?

As a creative producer, I fully identify with Fares when he says that an artist’s work is never finished. The multitude of interpretations of a piece, a film, or a painting is evidence of maturity. A film can be improved infinitely, but deadlines must be met. Ultimately, a musician needs to perform a piece; a filmmaker needs to release a film.

We tried to illustrate the effect of Chopin’s music in several ways— the reactions of the audience: tears, contemplation, reflection, and silence; their individual observations, what they felt while listening to the piano in places marked by pain. Depicting the musicians’ reactions was critical, too, especially Fares, who seemed to channel each note emotionally. The final device we used was to interweave the entire performance with symbolic images— shots of the Auschwitz, Birkenau concentration and extermination camp, views of refugees from a camp in Beirut and the destroyed port, and landscapes of South Korea near the border with North Korea. Our goal was to create a mix of extreme emotions compressed into the final climactic scene of the film.

From the beginning, you juxtapose serene and idyllic nature scenes with urban scenes, vistas, and art with barbed wire and destruction. Can you describe how you chose the visual cues?

Maciej Pawelczyk during the shooting of the documentary

You have discerned our narrative mechanism! The most potent artistic expression lies in contrasts, hence our decision to juxtapose such polarizing images. Isn’t this the same in music? For instance, the enchanting landscapes of a town where a barefoot Polish composer wanders through the forest are set against the harrowing extremity of Auschwitz; the captivating mountainous vistas around Seungil Bridge, are contrasted with the barbed wire beyond which lies the cruel ‘state of darkness,’ North Korea; or the splendid city of Beirut, juxtaposed with the aftermath of a port explosion and the plight of Syrian refugees.

You feature both auditory and visual metaphors, such as barbed wire and railroad tracks. Later in the film, there are several shots where these images become ubiquitous, and we cannot pinpoint where they are located.

Indeed, barbed wire is a recurring motif—barbed wire symbolizes enslavement, of course.

It appears in the refugee camp in Lebanon, in Auschwitz, and on the border of the two Koreas.

In North Korea, barbed wire symbolizes not just the physical confinement of almost 26 million people but a broader spectrum of state control, oppression, and isolation, both from the outside world and within its borders. The importance of this symbol is even more significant since some 5 million soldiers and civilians died in the Korean War, which led to the division of the country.

In the context of Syrian refugees residing in Lebanon, barbed wire marks the boundaries of refugee camps or enclosures where Syrian refugees live and represents the displacement these individuals have experienced after being forced to leave their homeland due to war and conflict caused by Bashar al-Assad. Over 12 million Syrians remain forcibly displaced from their homes, including an estimated 1.5 million who fled to Lebanon, a country of only 7 million.

The railway tracks in Auschwitz stand as a stark emblem of destruction, deeply linked to the camp’s dark history. These tracks saw the arrival of 1.3 million individuals to Auschwitz. Notably, in just 5 years, 1.1 million were Jewish, with 960,000 succumbing within the camp’s confines and 200,000 others perished, mainly non-Jewish Poles, individuals with mental disabilities, Roma, homosexuals, and Soviet POWs.

These haunting symbols are a stark reminder of the dire outcomes that can emerge when authoritarian regimes rise to power. Our film stands as a manifesto against all forms of physical and mental subjugation of people.

There are several times in the movie when the piano music of Chopin returns. I felt myself calm. The Scherzo in C-sharp, composed in 1838 minor Op. 39, is featured prominently. The piece, composed in an abandoned monastery in Spain, is a terse, heroic, and grand work. It vacillates between the mysterious with lovely high fleeting passages, then moves to aggressive octave passages.

All three musicians had something to give to bring calm or healing to the lives of their audience members. But you also use disturbing sounds and silence very effectively.

I took a creative part in deciding the direction of the film’s musical arrangements; indeed, Frédéric Chopin’s music does not dominate the film as you can’t tell a story on one level of emotion. Dynamics are the basis of narrative, and if we played Chopin’s music continuously, its power would be less weighty.

And that is the same in music. What would an interpretation be like all in monotone without contrasting dynamics?

We keep viewers in suspense, waiting for the climax at the film’s end, when the Chopin compositions dominate and bring utter relief. Disturbing sounds within the film only intensify this effect, causing a dissonance between the state of exaltation and the darkness associated with places of evil.

I found it particularly effective that the three performances are aligned. Would you comment on what your intention was for the viewers?

Our film is not only a concert but a cinematic endeavor carefully crafted to captivate, enchant, and grip the viewers. In weaving the performances of our three pianists together, we hoped to harness a profound synergy. Channeling Chopin’s music and the all-encompassing benevolence of the sounds into a decisive moment is akin to what would happen if we focused sunlight through a magnifying glass. This confluence of energies could not have been achieved by showcasing each performance separately.

I think in a world where understanding and harmony between cultures should be paramount, particularly in these times fraught with uncertainties and conflicts, the film is a testament to the unifying power of music. The three threads – Arabic, Jewish, and Korean – intertwined artistically that converge in a climactic final scene shows we are one, bound together by the universal language of music and its ability to bridge the divides of our human experience. I hope our film highlights that.

The emotions raised are powerful. Do you think the three musicians achieved their goals? What did these experiences do for them?

This is a good question because we spoke with the film’s protagonists after we concluded the film. One thing is sure: for everyone, it was an unprecedented, once-in-a-lifetime experience.

For Fares Marek Basmadji, the concert met expectations and allowed him, in a sense, to get in touch with a part of himself. He told us that he couldn’t stop thinking about the people he met there and that the experience gave him a broader perspective on life.

Jae-Yeon Won mentioned that before the film his knowledge of the Korean War was only through books and movies. He fell in love with Chopin’s unique harmonies and bel canto style, but on the bridge, he experienced an inexplicable shuddering. It reinforced Jae-Yeon’s belief that Chopin’s music can be a powerful tool to reach and soothe those suffering from trauma.

Leszek Możdżer, was always confident about the outcome of our musical experiment. We accomplished our mission, a sentiment underscored by his quote, “I am not afraid of darkness,” which inspired the film’s title.

Were there any unexpected outcomes?

As a producer based in Poland, I couldn’t have imagined that the Syrian crisis and the brutal Russian attack on Ukraine would echo so poignantly in my backyard. The parallels between the Syrian and Ukrainian situations have become strikingly clear, especially as I witness the influx of Ukrainian refugees seeking refuge in Poland.

I think the enduring strife in the Middle East makes this film even more timely. The two narratives, the Arabic and the Jewish are woven together and culminate in an emblematic union.

The Seungilgyo Bridge divide continues to resonate powerfully. The escalating tensions at the Korean border, the advancements in lethal technologies, and the strengthening bonds among authoritarian regimes are distressing reminders of today’s reality.

You have a passion to highlight political divisions and tumult. Tell us about your other projects.

Authoritarian governments often start by subtly eroding freedoms gradually, imperceptibly, by creating false narratives and even fake foes through propaganda. This underscores the importance of vigilant media coverage, which I try to promote as a producer.

In our international documentary television series “Auschwitz in 33 Objects,” we present the history of the concentration and extermination camp unconventionally through objects discovered in the camp that belonged to the victims. We are just completing the “Dictator’s Hideouts” series, which explores the bunkers of European dictators and the unique paranoia of each dictator. Isn’t it essential to draw lessons from the past?

Chopin: I am Not Afraid of Darkness, is available on IMDb. A final quote from the documentary is, I think, apt.

“Music is a kind of language that is very close to God.”

No comments:

Post a Comment