Klaus Döring's Classical Music/Klaus Döring's Klassische Musik

It's all about the classical music composers and their works from the last 400 years and much more about music. Hier erfahren Sie alles über die klassischen Komponisten und ihre Meisterwerke der letzten vierhundert Jahre und vieles mehr über Klassische Musik.

Total Pageviews

Sunday, October 12, 2025

Smetana: Vltava (The Moldau) - Stunning Performance

Saturday, October 11, 2025

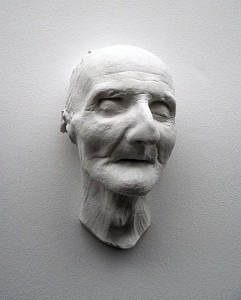

The Morbid Compulsion of Anton Bruckner

by Georg Predota

Having been born, raised and educated in rural Austria ill prepared Anton Bruckner (1824-1896) for the acidic and highly competitive musical environment of imperial Vienna. Retaining his shy and unassuming demeanor throughout his life, Bruckner presented a wide target for music critics, journalists and composers alike, with most famously perhaps, Johannes Brahms referring to him as a “country pumpkin.” Much of this deep-seated resentment focused on Bruckner’s total admiration for Richard Wagner and a highly idiosyncratic and expansive musical style. The reaction to his Symphony No. 6, partially completed in 1881, was predictably swift and severe. The music critic Eduard Hanslick—a close personal friend of Johannes Brahms—perceived “a clever and original work in which inspired moments alternate frequently without recognizable connections; full of barely understandable platitudes, and empty and dull patches that stretch to unsparing lengths.” It’s not surprising that Bruckner was prone to suffer from debilitating insecurities that made him revise his works multiple times.

But Bruckner had other problems as well! For one, he had a compulsion to count things continually. In medical terms, this is called “numeromania” and professionally classified under compulsive disorders. He obsessively counted windows of building, cobblestones on the road, and number of bricks in a wall. Even worse, he continually counted the number of bars in his enormous orchestral scores to make sure their proportions were statistically correct. He once even tipped a conductor with cash for getting through a rehearsal of one of his symphonies. In his diaries, he kept long lists of teenage girls he fancied, and to their surprise, frequently propositioned them. All his life, Bruckner was fascinated with death. For one, when his mother died, Bruckner commissioned a photograph of her corpse, and kept it in his teaching room. He did not have a single image of his mother when she was alive, just the eyes of the dead woman staring at him and his students.

Bruckner eventually developed an obsession with viewing dead bodies. He became a frequent visitor at funeral parlors and in cemeteries, viewing the bodily remains of total strangers. He sought permission to exhume and see the body of his dead cousin, a request that was refused by local authorities. Bruckner even applied to see the corpse of Emperor Maximilian, whose body had been returned to Vienna after his execution in Mexico in 1867. When the remains of Beethoven and Schubert were moved to Vienna’s Central Cemetery in 1888, Bruckner just had to be there. Eyewitness accounts recall that Bruckner “fingered and kissed the skulls of both composers.” Given Bruckner’s obsession with death, it is hardly surprising that he gave very specific instructions on how to deal with his own dead body.

On 11 October 1896, Anton Bruckner died at age 72 in Vienna. His body was initially released for viewing at the St. Charles Church in Vienna, and five days later arrived at the St. Florian Monastery in his hometown of Linz. Between the viewing in Vienna and the burial in Linz, a certain Professor Paltauf mummified Bruckner’s body, just as the composer had specified in his will! In 1996, in preparations for the Bruckner centenary celebrations, it was discovered that the Mummy had begun to decay. As such, the Monastery arranged for the Mummy to take a secret restoration trip to Switzerland. Restored in body and clothing, Bruckner returned to Linz and officials pronounced the result “like he died yesterday.” Bruckner’s obsessions and compulsions left traces in his compositions. You just have to listen to the chilling and dehumanized orchestral landscape in the final movement of his 4th symphony, or the emotional desolation of the slow movement of his 7th. And don’t forget the aggressive, apocalyptic and despairing visions of cosmic pain in the third movement of his unfinished 9th symphony!

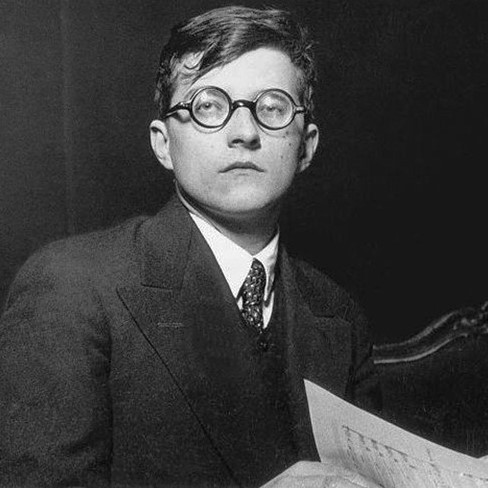

The Piano Legacy of Dmitri Shostakovich

by Hermione Lai

Dmitri Shostakovich

Everything seems full of restless energy with angular melodies interrupted by moments of aching lyricism. Much of it is not just music, but a story that doesn’t quite resolve, and I’m certainly hooked on figuring out what he’s trying to say.

Irony and Hidden Truths

Much of his music strikes a balance between a wiry and percussive drive and ghostly, introspective passages. It’s like he’s painting a picture of an uncertain world, but at the same time clinging to slivers of hope.

I am no virtuoso, but there’s something about his music that makes me want to lean in closer, to uncover the layers of irony and heart he’s tucked away. It’s not always easy listening, but it’s the kind of music that makes you feel like you’re discovering something true.

As we commemorate the 50th anniversary of his death this year, let us explore the world of Shostakovich’s piano music, where every note pulses with raw emotion and hidden stories waiting to be unravelled.

First Piano Sonata

Dmitri Shostakovich

During his days at the Conservatoire, Shostakovich was ranked as a promising concert pianist, and the instrument remained important throughout his career. He wrote some of his most important works for the piano, and he usually played the piano parts of his chamber works and songs at their premiere.

Shostakovich was just 20 years old when he wrote his first Piano Sonata Op. 12. It’s a wild and youthful burst of energy that shows his early genius and his love for pushing boundaries. When his piano professor first heard the work, he commented, “Is this a piano sonata? No, it’s a sonata for metronome with piano accompaniment!”

This bold, single-movement of jagged rhythms, sharp dissonances and sudden mood shifts is terribly difficult to play. And just listen to the aggressive percussive passages with some fleeting lyrical moments. It’s full of avant-garde spirit and virtuosic flair with hints of Prokofiev and even Stravinsky.

Aphorisms

Dmitri Shostakovich

The next piano work of Shostakovich goes off in a completely different direction as he composed a cycle of ten miniatures for piano, eventually titled Aphorisms. Written in Leningrad during his early experimental phase, these miniatures are witty and modern.

Each piece is titled evocatively, including Recitative, Serenade, Nocturne, March, and others, and has a distinct character. It’s like a musical sketch capturing a fleeting mood or idea. A scholar tells us that Shostakovich “subverted the traditional expectations implicit in the title into a ruthless and vinegary application.”

The musical world is turned upside down as we find atonal modernity and a number of caricature-like movements. That Nocturne is not hinting at things that go bump in the night but graphically depicts them. Plenty of sly humour and subtle melancholy and much youthful experimentation, if you ask me.

Dmitry Shostakovich: Aphorisms, Op. 13 (Melvin Chen, piano)

Second Piano Concerto

Dmitri Shostakovich

The piano plays multiple roles in the hands of Shostakovich, and that includes 2 Piano Concertos. Both concertos are relatively short, reflecting his preference for concision and clarity. Above all, they showcase his ability to blend classical forms with modern, often satirical elements.

While the first concerto is a severe, biting, and anguished composition, the Second Piano Concerto, written in 1957, was a birthday present for his son Maxim. As such, it is good-natured, vibrant and sparkles with wit and warmth.

A playful woodwind intro leads to a lively piano melody, and a march-like bugle call shifts to a lyrical theme. The second movement bares raw sadness with a tender piano melody, and the third movement snaps back to a carefree tune. It all ends with a joyful flair, and according to some pianists, “it is one of the most fun concertos to perform in the entire piano repertoire.”

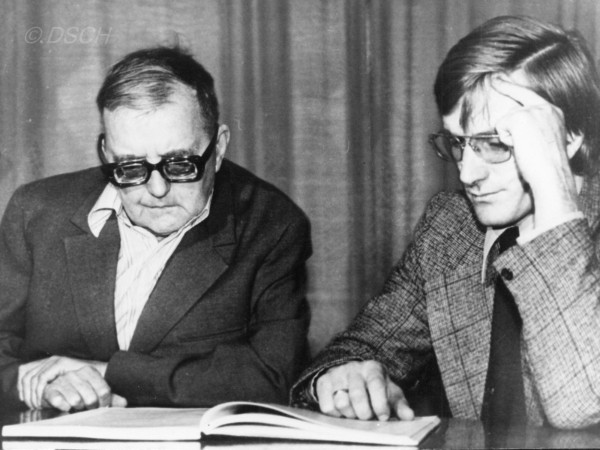

Concertino for 2 Pianos

Shostakovich seriously considered pursuing a career as a concert pianist. However, after only winning a medal of honour at the Warsaw Chopin Competition in 1927, he decided to follow his calling as a composer.

Maxim Shostakovich, the composer’s son, was also a piano prodigy. Shostakovich composed the Concertino for two pianos in 1953 for Maxim as a kind of entrance examination for the Moscow Conservatory.

Maxim Shostakovich, 1967

The single-movement work provides plenty of material for young soloists to excel in front of their audience. It is an impassioned work with heavy dotted rhythms and a characteristic forward drive. There is plenty of room for virtuosity and two very attractive themes. One is emphatically melodic and the other march-like. Maxim premiered the piece alongside fellow student Alla Maloletkova in 1954.

Concerto for Piano and Trumpet

Let’s feature one more concerto, specifically the “Concerto for piano and trumpet”, also known as the Piano Concerto No. 1 in C minor. Shostakovich unleashed his piece in the spring of 1933, and ever the musical provocateur, he blended the virtuosic flair of the piano with the brassy interjections of a solo trumpet.

This concerto was composed at the height of Shostakovich’s youthful exuberance. It crackles with a theatrical energy that veers from playful mockery to poignant lyricism. The piano drives the narrative with dazzling runs and biting rhythms, while the trumpet punctuates the dialogue like a wry commentator in moments of jazzy bravado.

This work pulses with Shostakovich’s signature irony, weaving quotations from Beethoven and Haydn into a modernist tapestry that both celebrates and subverts classical traditions. The trumpet part was inspired by the composer’s fascination with popular music and theatre, evoking everything from circus antics to heartfelt speeches.

24 Preludes

In 1932/33, Dmitri Shostakovich poured his restless imagination into the 24 Preludes, Op. 34. It is a cycle of piano miniatures that traverse every major and minor key with a chameleon-like range of emotions.

Each prelude is a fleeting world unto itself. Some sparkle with sardonic wit, others brood with introspective melancholy, while a few erupt in virtuosic bursts of energy. Essentially, Shostakovich weaves a tapestry of contrasts between irony and veiled tragedy.

Shostakovich blends the romantic echoes of Chopin with the sharp edges of modernist dissonance and hints of Russian folk song. These works shimmer with immediacy, delivering emotional punches; the cycle offers a whimsical, haunting, and defiant journey through Shostakovich’s inner landscape

Second Piano Trio

Father and Son Shostakovich

In this little survey of the piano works by Shostakovich, we should also take a quick look at the piano’s role in his chamber music. The work that stands out to me is the Piano Trio No. 2. It was written in the summer of 1944, during a time of mourning for personal and collective losses amidst the horrors of World War II.

This four-movement trio is a tapestry of anguish and resilience, music infused with a raw and almost unbearable emotional weight. The interplay of instruments creates a dialogue that feels like a requiem for a fractured world. Some commentators call it “the composer’s unspoken rage against the brutality of his time.”

Premiered in November 1944 by Shostakovich and members of the Beethoven Quartet, the trio stunned listeners with its emotional directness and technical demands, cementing its place as one of his most profound chamber works. The piano serves as both a driving rhythmic force and a poignant lyrical voice, alternating between sharp intensity and tender introspection.

Second Piano Sonata

Shostakovich’s 2nd Piano Sonata was composed in 1943, and it is also a deeply introspective work. This three-movement sonata also reflects a musical shift from youthful exuberance to a more mature, contemplative voice.

Shostakovich, then in his late 30s, pours his personal and political struggles into the music and creates a soundscape that feels both intimate and universal. The heart of the sonata lies in the second movement, a haunting Largo that unfolds like a quiet lament with the piano weaving hesitant melodies that seem to mourn yet cling to hope.

The final movement drives with relentless energy, featuring intricate counterpoint and syncopated rhythms that culminate in a powerful yet bittersweet close. One needs technical precision and emotional maturity as a pianist to convey the layered complexity. This is one more exploration of Shostakovich’s inner works, simultaneously raw, reflective, and profoundly moving.

For Shostakovich, the piano becomes a most versatile and expressive voice. The instrument carries his signature blend of intensity, irony, and introspection across genres. The piano in Shostakovich’s hands, conveying personal struggle, subtle humour, or profound resilience, is one of the most intensely emotional storytellers in music.

Ten Greatest Women Violinists of All Time

by Emily E. Hogstad

For generations after the invention of the instruments, the violin was widely considered to be a masculine instrument.

Despite this, from the eighteenth century on, women have flocked to this instrument and succeeded at the highest levels.

Today, we’re looking at the life and work of ten women from the history of violin playing, all of whom have made huge impacts on the art.

Maddalena Laura Lombardini Sirmen (1745–1818)

Portrait of Maddalena Laura Sirman (artist unknown)

Maddalena Laura Lombardini was born in 1745 in Venice.

As a girl, she studied at the music school at the San Lazzaro dei Mendicanti. While there, she showed special musical promise and went to Padua, Italy, to study with Giuseppe Tartini (composer of the famous Devil’s Trill sonata).

She graduated in 1767 and married violinist Ludovico Sirmen that same year. The two performed together and co-wrote music, including a double violin concerto that sadly has not survived.

In the late 1760s, when she was in her early twenties, she published her six violin concertos. Leopold Mozart, Wolfgang’s father, praised the first, calling it “beautifully written.”

She became one of the first composers to write string quartets, publishing a collection in 1769, shortly after Haydn’s early efforts in the genre.

In the 1770s, she began appearing as a singer, but her singing was not as successful as her violin playing had been.

As tastes changed, her violin-playing eventually came to be seen as too “old-fashioned.” She died in 1818, having lost much of her net worth after Napoleon’s invasion of Italy.

Teresa Milanollo (1827–1904)

Teresa Milanollo was born in 1827 in Savigliano, Italy, to a violin maker and his wife. When she was four, she heard a violinist play at church and demanded to be taught.

Initially, she took lessons locally, then moved to Turin for further studies when she was eight. By nine, she was studying in Paris in between extensive concert tours.

In 1838, she began teaching her younger six-year-old sister Maria how to play the violin. The two would become frequent performance partners.

Teresa Milanollo

Before the Milanollo sisters began touring Europe, the violin was widely seen as an instrument unsuitable for women. The charming sisters changed that.

Audiences weren’t the only people impressed; so were critics and composers. Berlioz wrote a glowing review of Teresa in 1841. A few weeks later, she performed for Chopin. The following year, they played with Liszt before royalty.

The Milanollos continued their triumphant tours until the summer of 1848, when sixteen-year-old Maria became sick with tuberculosis. She died that October.

After the death of her sister, a devastated Teresa began playing only for the benefit of charity. She would hold one concert for a paying audience, then hold an identical one for impoverished schoolchildren and their families, and distribute the money she’d just earned.

On 16 April 1857, she gave her farewell performance. Hours later, she married a military engineer named Theodore Parmentier. She followed societal custom and retired from the stage after her wedding, although she continued to play privately and occasionally performed for charity or at home.

She died in 1904.

Wilhelmina Norman-Neruda (1839–1911)

Wilhelmina Norman-Neruda

Wilhelmina Neruda was born in Brno, Moravia, to the organist at Brno Cathedral and his wife, who had several children who went on to become child prodigies. Wilhelmina would become the most famous of all of them.

Her father initially wanted her to play piano, but when she was a child, he caught her playing her brother’s violin. She was so naturally talented that he permitted her to continue.

The family moved to Vienna, and she began studying with Leopold Jansa. Wilhelmina gave her first public performance at seven. She and her talented siblings later began touring Europe to acclaim.

In 1864, when she was thirty-three, she married composer Ludvig Norman. She had two sons with him before the marriage deteriorated, and they separated.

Norman died in 1885, and three years later, Wilhelmina married renowned conductor and pianist Charles Hallé. When he was knighted, she became known as Lady Hallé.

Wilhelmina became famous across Europe, but especially in her adopted homeland of Great Britain. Sir Arthur Conan Doyle famously had Sherlock Holmes attend one of her concerts in the 1887 novel A Study in Scarlet.

She especially enjoyed performing chamber music and gave many incredible performances. These were striking at the time because she was one of the first women players to publicly perform chamber music with men in integrated ensembles. This would eventually help pave the way for women to play in orchestras with men.

She was widowed for a second time in 1895, and in 1898, her son was killed in a mountaineering accident. She retired from the concert stage the following year and moved to Berlin to focus on teaching.

She died in 1911.

Camilla Urso (1840–1902)

Camilla Urso

Camilla Urso was born in Nantes, France, in 1840, to an Italian flute player and his French singer wife.

Like Wilhelmina Norman-Neruda, she first heard the violin in church when she was a little girl and begged her father for lessons. She began playing the violin when she was six years old, and began playing for hours a day.

She enrolled at the Paris Conservatoire in 1849, the month she turned nine. (Rossini was on her audition panel.) She became the first woman violinist allowed to study there and graduated in 1852.

Later that year, she and her family sailed to New York, where she began touring America. During this decade, while Wilhelmina Norman-Neruda was inspiring European girls to take up the violin, Camilla Urso was doing the same in America.

In the mid-1860s, she returned to Europe to tour. Over the following decades, she would appear on four continents: North America, Europe, Australia, and Africa.

After fifty years of concertizing, she retired from the stage and began focusing on teaching. She died in 1902.

Maud Powell (1867–1920)

Maud Powell

Maud Powell was born in 1867 in Peru, Illinois, a small town a hundred miles southwest of Chicago. She began taking violin and piano lessons when she was seven years old. Her talent quickly became obvious.

When she was thirteen, her parents sold their house to fund studies in Europe. While there, she studied with Henry Schradieck in Leipzig, Charles Dancla in Paris, and Joseph Joachim in Berlin.

She made her Berlin Philharmonic debut in 1885, at the age of eighteen. It was the beginning of a major career.

Powell became the first great American violinist, male or female. Her legacy lives on in three important ways.

First, she used her fame to spotlight contemporary composers. She gave the American premieres of the Sibelius, Tchaikovsky, and Dvořák violin concertos, all of which have since entered the permanent repertoire. She was also a strong advocate for the work of American women and Black composers.

Second, she was also on the cutting edge of recording technology, making dozens of recordings between 1904 and 1919, the year before her death.

Third, during her American tours, she made a point to stop in dozens of tiny towns in between her big city appearances, sparking interest and curiosity about classical music across America.

Her intense workload was presumably one of the triggers of a fatal 1920 heart attack, which happened immediately after playing her transcription of the Black spiritual “Nobody Knows the Trouble I See.” She collapsed onstage and died.

Marie Hall (1884–1956)

Marie Hall

Marie Hall was born in 1884 in Newcastle upon Tyne, England. Her father, a harpist with a touring opera company, was her first teacher.

The family had very little money, and despite her extraordinary natural talent, her training was intermittent. She studied violin with composer Edward Elgar in 1894, August Wilhelmj in 1896, and Johann Kruse in 1900.

In 1901, at the age of seventeen, she finally found funding to pay for studies with Otakar Ševčík in Prague, one of the best-known teachers of the era.

She made her London debut in 1901 with a staggeringly difficult program: Paganini’s first concerto, Tchaikovsky’s violin concerto, and Wieniawski’s Fantasy on Themes from Faust.

She would go on to perform in Europe, North America, Australia, and Asia.

She also made a number of wonderful recordings, including, in 1916, the first recording of excerpts from the Elgar violin concerto, with the composer conducting from the podium. She performed in a cone with the orchestra behind her.

Ralph Vaughan Williams dedicated his famous showpiece, The Lark Ascending, to her. She played the premiere of the violin and piano version in 1920 and the violin and orchestra version in 1921.

In 1911, she married her manager and had one child, a daughter. She died in 1956.

Ginette Neveu (1919–1949)

Ginette Neveu

Ginette Neveu was born in Paris in 1919. She was the grand-niece of composer Charles-Marie Widor.

She was an astonishingly talented little girl who made her debut in Paris at the age of seven, playing the Bruch concerto.

She went to study at the Paris Conservatoire and studied with Nadia Boulanger, George Enescu, and Carl Flesch. She was so talented that Flesch gave her lessons free of charge.

In 1935, when she was fifteen, she won the Henryk Wieniawski Violin Competition. (Legendary violinist David Oistrakh, twenty-seven, placed second.) The win catapulted her to the forefront of the classical music world.

After World War II ended, she began making her major international debut. She and her accompanist brother embarked on a series of performances across Europe, North America, and South America.

Tragically, both Neveus died in a plane crash in 1949, flying between Paris and New York.

Her early death robbed the classical music world of one of its brightest stars. She had fewer opportunities to record than other violinists who lived longer, but the recordings she left behind are deeply beloved.

Kyung-Wha Chung (1948–)

Kyung-Wha Chung

Kyung Wha Chung was born in Seoul in 1948. She began playing piano at four and violin at seven. At nine, she made her debut in the Mendelssohn violin concerto with the Seoul Philharmonic.

Her six siblings all played musical instruments, and when she was thirteen, the family moved to the United States to further their educations. She began studying at Juilliard under Ivan Galamian.

In 1967, when she was nineteen, she, along with Pinchas Zukerman, won the prestigious Leventritt Competition, which helped launch both of their respective careers.

Three years later, she stepped in as a replacement for Itzhak Perlman in London. The performance was so sensational that she was immediately hired to make a recording of the Tchaikovsky and Sibelius violin concertos with the orchestra.

In 2008, she withdrew from the concert platform due to injury and poor health, but returned to the stage in 2014.

In 2016, she made her first recording in fifteen years: a recording of the six sonatas and partitas for solo violin by Bach, widely considered to be the Mount Everest of the repertoire.

Anne-Sophie Mutter (1963–)

Anne-Sophie Mutter

Anne-Sophie Mutter was born in the town of Rheinfelden, Germany, on the border between Germany and Switzerland, in 1963. Her family was not musical, but loved classical music.

She began studying the piano when she was five, but soon switched over to the violin after hearing a recording of the Mendelssohn and Beethoven concertos. She gave her first public concert in 1972, when she was nine.

When she was thirteen, Herbert von Karajan, legendary conductor of the Berlin Philharmonic, heard her playing and became her mentor. She made her first recording of two Mozart concertos when she was just fifteen.

She made her American debut with the New York Philharmonic in 1980, kicking off a decade of touring and recording.

Starting in the 1990s, she became increasingly interested in contemporary music. Over the ensuing decades, a number of composers have written concertos and other works for her.

She has earned a reputation as someone interested in ambitious projects. For instance, in 1998, she spent an entire year playing and touring the Beethoven violin sonatas. Later, to observe the 250th anniversary of Mozart’s birth in 2006, she toured performing all of the concertos.

In addition to her musical activities, she has also played benefit concerts to support charitable causes, from famine relief to Holocaust awareness, among many others. In 2021, she was elected President of German Cancer Aid.

Hilary Hahn (1979–)

Hilary Hahn

Hilary Hahn was born in 1979 in Virginia and grew up in Baltimore. She began playing the violin in a Suzuki program there when she was three years old.

When she was ten, she began studying at the Curtis Institute of Music in Philadelphia with Jascha Brodsky. At the time, Brodsky was eighty-three years old and a former student of Eugene Ysaye, who had himself been born in 1858. This training gave her unique direct insight into musical ideas from the early twentieth century.

She made her American orchestral debut with the Baltimore Symphony Orchestra in 1991 and her European debut in Hungary in 1994. Her debut recording was made when she was just sixteen: one of the finest recordings ever of three solo works by Bach. She graduated from Curtis with her bachelor’s degree in 1999 at the age of twenty, but by that time her international career was already in full swing.

Over the past two and a half decades, she has demonstrated a flawless technique and an intellectually probing musical curiosity. She has proven to be one of the greatest violinists alive, male or female.

Wednesday, October 8, 2025

STYLISTICS - YOU MAKE ME FEEL BRAND NEW - original live audio!

Shine On You Crazy Diamond - Pink Floyd Live at London Earls Court

🌸 𝘽𝙄𝙉𝙄 𝙩𝙤 𝙝𝙚𝙖𝙙𝙡𝙞𝙣𝙚 𝘼𝙪𝙧𝙤𝙧𝙖 𝙈𝙪𝙨𝙞𝙘 𝙁𝙚𝙨𝙩𝙞𝙫𝙖𝙡 𝘿𝙖𝙫𝙖𝙤! 🎈