It's all about the classical music composers and their works from the last 400 years and much more about music. Hier erfahren Sie alles über die klassischen Komponisten und ihre Meisterwerke der letzten vierhundert Jahre und vieles mehr über Klassische Musik.

Total Pageviews

Tuesday, February 11, 2025

Beethoven - Symphony No. 7 (Proms 2012)

Reminisce and cherish those memories of love

Reminisce and cherish those memories of love through the songs of your life this Valentine's Day.

Friday, February 7, 2025

Music and Bows and Clothes: Oh My!

© Bass Bags

It’s hard to believe how many hilarious behind-the-scenes mishaps we musicians experience. Afterwards, once we’ve recovered from the embarrassment, we love to share these stories at parties!

My friend cellist Clay Ruede recently told me this one: He was playing a show on Broadway and he kept a cello at the theater. One Sunday the orchestra was advised that heavy storms were on their way and the theater basement could flood. It would be wise if the musicians removed their instruments from the lockers as a precaution. Clay took his cello home. The following Tuesday, the musicians gathered for the next show and chatted backstage while waiting for the “places” call. When the loud speakers announced, “Places please. Musicians, places,” Clay went to his locker but the cello wasn’t there. It was still at home. Thinking quickly, he ran out to a nearby music shop, he purchased a cheap cello, and got back to the theater and his seat just in time for his first solo. After the show Clay returned the cello for a full refund.

A couple of years later, Clay performed for a different Broadway musical. Just before Showtime a violinist in the orchestra called in a panic that there had been an accident on the highway. Frantic she would be late, she admitted that she’d also forgotten to bring her violin. Clay told her not to worry. He knew what to do! He left the theater, bought a violin for her at the same music shop, and placed the tuned violin and a bow on her chair. The violinist made it just in time for the performance.

© Violinist.com

Forgetting bows or instruments is more common than you might think! Another colleague described how many times his gear enjoyed traveling without him. Roland Hutchinson mentioned how his baryton bow once failed to get off the bus in Eisenstadt (not its fault) and the bow went on to Vienna without him. Fortunately, the bus line found the bow and it was returned without incident before the performance. Another time one of his viols “forgot” to get off the airplane in California and on it went to Hawaii (the airline’s fault). The carrier delivered the instrument to Roland by van the following day. When traveling to South Africa another colleague also left her bow on a plane. Upon reaching the baggage claim area she suddenly remembered the forgotten bow and in a panic raced back to the gate where she found the entire crew gathered around the long box. Lost in speculation they were trying to guess what this mysterious box contained: a flute? A pool cue? Some type of narrow rifle? A baguette?

Losing instruments happens on tour too! Gill Tennant recalls when her youth orchestra traveled to Moscow. An entire tranche of instruments went directly to Moscow but the group first had a concert in Copenhagen where the musicians disembarked. Oops! Fortunately, Copenhagen’s youth orchestra members were able to lend their instruments for the concert. The timpanist wasn’t too happy. The Copenhagen counterpart didn’t have any timpani. This is especially problematic in the fourth movement of Shostakovich Symphony No 5. The timpanist had to stand on a stool to bang on an enormous 15-foot-tall side drum.

© Orquestra Imperial

Forgetting music is a classic faux pas. Fortunately, many musicians have phenomenal memories at times like these but forgetting where you’re supposed to be going is another story. Freelancers who often have to travel to several different venues find this a frequent mishap. Imagine the chagrin. A colleague played an entire wedding gig. When she asked the bride’s father for payment he was puzzled. They hadn’t booked any musicians. He’d actually thought it was such a nice perk that the venue provided a string player. Meanwhile at the same venue another wedding party wondered what happened to the musician they booked.

It’s easy to show up at the wrong hall. A colleague realized her error and had to walk a half mile on a hot afternoon across town wearing her long black dress and high heeled shoes and of course carrying, a music stand, music bag, and the cello. She made it to the performance on time.

Wardrobe failures plague us too. I remember wearing a lovely sheer cream and rose-colored dress for a chamber music concert. The bright stage lighting shone from behind us. My chamber music partners leaned toward me and whispered that the audience could see right through my skirt. They accommodated this turn of events by standing directly behind me while we exited the stage, trying unsuccessfully to keep a straight face. We’d hoped the Charles-Marie Widor Piano Quartet in A Minor Op. 66 would be alluring but not that alluring!

Years ago, Clay’s trio was about to make its Washington, DC debut at the Philips Gallery. The Gallery was being renovated, so the concert had to be held at a different venue. There the stage was 8 feet above the audience with the “backstage area” located behind the audience. The musicians had to walk through an aisle in the center of the audience and up a staircase in the middle of the stage to get into playing position. For the Sunday afternoon concert the musicians wore suits and not their customary tails. Clay’s cello was lying in its case on the floor of the so-called “green room.” When he bent over to pick up the cello he heard an embarrassing riiipppp. His pants split all the way from the waistband in the back to the zipper in the front. The pianist sprang into action and followed Clay very closely as they marched back and forth through the audience. Despite everything they got a rave review in the Washington Post, and in hindsight, he said, he was much cooler playing the concert with the additional ventilation.

From John Field to Alexander Scriabin: The Russian Nocturne

by Hermione Lai, Interlude

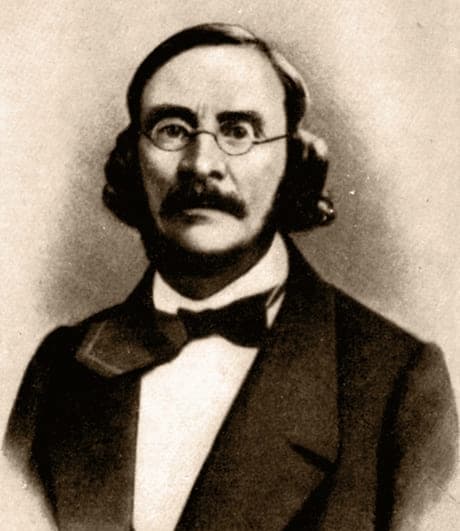

Anton Wachsmann: John Field, ca 1820 (Gallica: btv1b84179686)

On occasion, one can still hear performances of the Field Nocturnes in the concert halls, but they seem to have been relegated to preparatory exercises for the magnificent Nocturnes of Frédéric Chopin. He took on the legacy of Field’s invention and took this new salon genre to a deeper level of sophistication.

In light of Chopin’s achievements, it is easy to forget that Field’s influence was also felt in Russia. Field made Russia his home between 1802 and 1829, and he was deeply admired as a performer. However, he also set up a highly successful private piano studio, which contributed to the establishment of the Russian piano school and to Russian music itself. Will you join me on a journey through the wonderful world of the Russian Nocturne?

The Glinka Connection

Michael Glinka: Nocturne in E-Flat Major

When I started looking for John Field’s Russian connections, I came across the marvellous website of pianist and scholar Daniel Pereira. He embarked on an ongoing 15-year research project that looks at the history of universal pianism and its interpreters and teachers. It’s called “Piano Traditions Through their Genealogy Trees” and features thousands of piano connections throughout time, including pianists, teachers and the establishment of national and regional schools of playing.

Mikhail Glinka

Thanks to Daniel Pereira, we can now trace the students of John Field and their role in the Russian Nocturne tradition. One of the biggest names to emerge is Mikhail Glinka (1804-1857), who is generally regarded as the father of Russian music. Apparently, Glinka had a number of piano lessons from Field, and we know that his operas “A Life for the Tsar” and “Lyudmila” are cornerstones of a Russian tradition.

Glinka was surprisingly well travelled, and he personally knew Donizetti, Bellini, Mendelssohn, Berlioz, Auber, and Victor Hugo. But even more interesting for this blog, he also composed a number of piano pieces, including several Nocturnes. His “Nocturne in E-flat Major” dates from 1828 but was published only fifty years later. Some commentators call it “the first Russian Nocturne,” and the connection to Field is obvious. The beautifully flowing and melancholy Nocturne in F minor dates from 1839 and was written for Glinka’s sister while she was away, hence the title “The Separation.”

The Rubinstein Connection

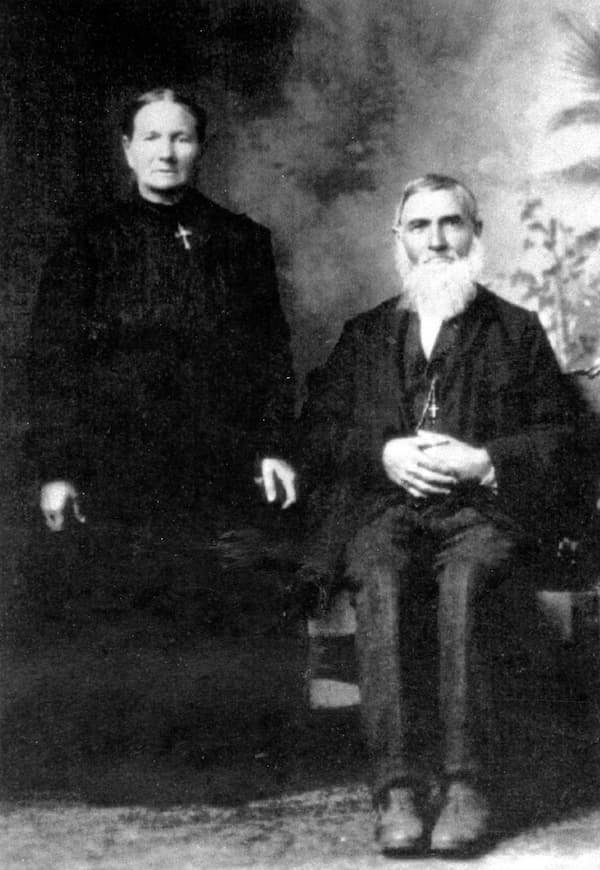

Alexander Villoing

Alexander Villoing (1804-1878) was born of a French émigré family and he studied piano with John Field in Moscow. By 1830, in the tradition of his teacher, he had established his own piano studio and soon enjoyed a reputation as one of the best pedagogues in Russia. Most significantly, in 1837 he was tasked with teaching the eight-year-old Anton Rubinstein. In fact, he is still considered Rubinstein’s only teacher and one of his best friends.

Villoing accompanied his young charge on a European concert tour between 1840 and 1843. He once again toured with Anton, his brother Nikolai and their mother Kalerija Christoforovna between 1844 and 1846. And we know that he became a professor at the St Petersburg Conservatory in 1862, an institution founded by Anton Rubinstein.

Villoing not only taught at the St Petersburg Conservatory, he also published his “Piano School”, the École pratique du piano in 1863. That particular piano primer was also called “Exercises for the Rubinstein Brother.” It was adopted as the official piano method at the Conservatory, republished several times, and even translated into German and French.

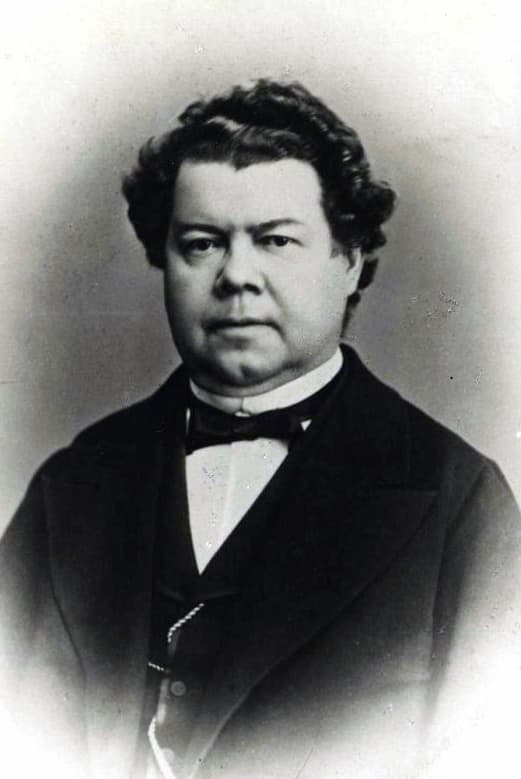

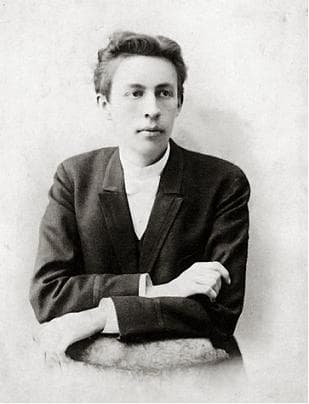

Anton Rubinstein, 1842

As a student of Field, Villoing was almost certainly introduced to the Nocturnes, a tradition he passed on to Anton Rubinstein. Rubinstein started to compose at the age of 12 and established world fame as a pianist. However, he was always keen to establish himself as a composer, and “he was the first Russian composer whose works for solo piano embodied the same serious artistic ideas as his symphonies and chamber music.”

In all, Anton Rubinstein composed eleven Nocturnes, two of them for piano four hands. Thematically charming and pianistically perfect, the Rubinstein Nocturnes are written with great skill and refinement. A critic suggests, “rather than plumbing the deepest emotions, they are far above the average Romantic salon music.

The Tchaikovsky Connection

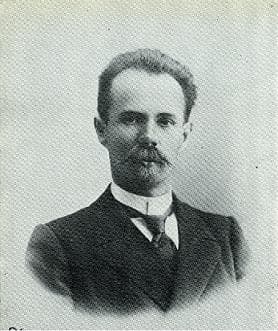

Anton Gerke

Among Field’s students, we also find the pianist, composer and teacher Anton Gerke (1812-1870). He was the son of a Polish violinist, and he personally knew Liszt, Thalberg, and Clara Schumann. I don’t know much about his apprenticeship with John Field, but by 1831 he was appointed court pianist in St Petersburg. Gerke was also involved with setting up the Russian Music Society.

Anton Gerke taught at the St Petersburg Conservatory between 1862 and 1870, and among his students were Nikolay Zaremba, Nadeszhda Rimskaya-Korsakova, Modest Mussorgsky, and Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky. Of course, when we look at the Tchaikovsky connections, we also find Anton Rubinstein.

Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky: Two Pieces Op. 10, No. 1 “Nocturne in F Major”

Tchaikovsky and Anton Rubinstein did not get along at all. Tchaikovsky was a student in Rubinstein’s instrumentation classes in the conservatory’s first intake in 1862. Rubinstein was unquestionably the greatest pianist besides Franz Liszt, and he knew it. Rubinstein considered himself a successor of Schubert and Chopin, and he very much disliked Tchaikovsky’s music.

Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky

As Tchaikovsky later wrote, “In my younger days, I very impatiently blazed my way—tried to acquire a name and fame as a composer—and hoped that Rubinstein would help me in my quest for laurels. But I must confess with grief that Anton Rubinstein did nothing, absolutely nothing, to further my desires and projects.”

Tchaikovsky composed his two Nocturnes in the 1870s, and “they are generally regarded as real jewels of Russian music.” He almost certainly knew the Nocturnes by Field, Rubinstein, and Chopin, but he also seems to take his bearing from Glinka. A pianist writes, “Tchaikovsky’s nocturnes abound with the heartfelt poetry of everyday life, and in following Field, places floating melodies above repeated pulsating chords.” Tchaikovsky also loved to place his melodies in the cello register of the piano, “creating an almost orchestral texture.”

The Glazunov Connection

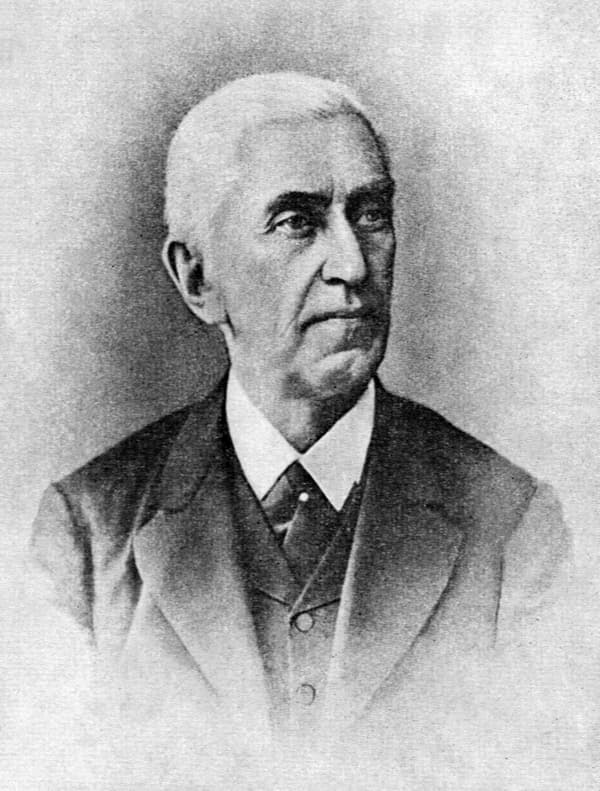

Alexander Dubuque

We must count the pianist and teacher Alexander Dubuque (1812-1898) among the most influential students of John Field. He was probably of French descent, and as one of the most influential teachers in Russia, Dubuque carried the piano tradition of John Field into the second half of the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries.

Among his most distinguished students were Balakirev and Nikolay Zverev, the teacher of Rachmaninoff, Scriabin, and Ziloti. Dubuque was known for an intellectually controlled, poised and precise style that became associated with the Field-Dubuque Moscow tradition. He even published a book on the technique of piano playing and one on his “Reminiscences of Field.”

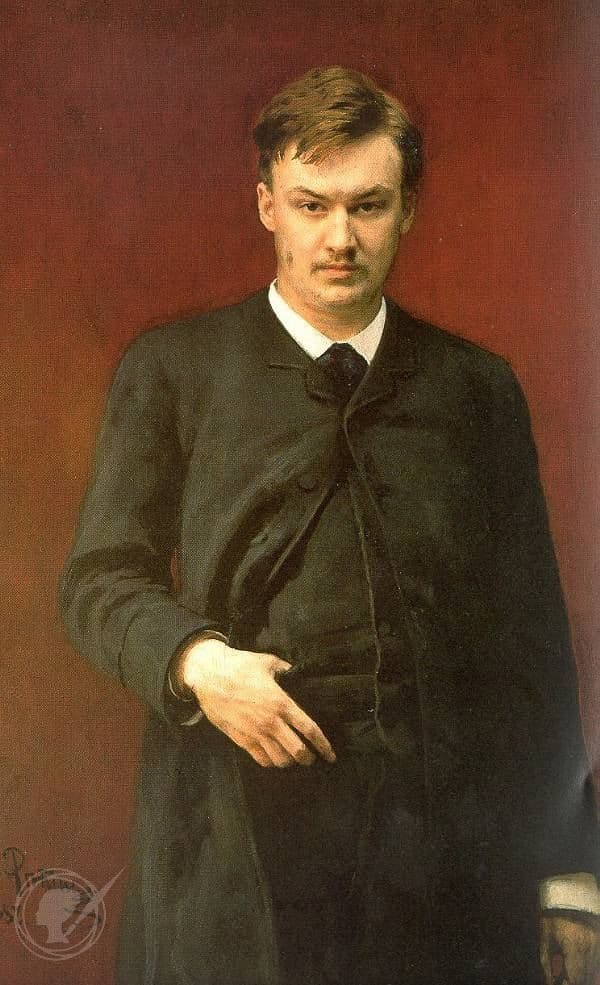

Mily Balakirev

Both Tchaikovsky and Balakirev dedicated piano pieces to Dubuque, and it was Mily Balakirev, a member of the famed “The Five,” who discovered Alexander Glazunov. Glazunov had started taking piano lessons at the age of nine and fashioned his first compositions at the age of 11. Balakirev took his early compositions to Rimsky-Korsakov, and among his early works, we find two Nocturnes. These youthful works show clear musical attention to texture, clarity of melodic line and harmonic sumptuousness, all attributes going back to John Field.

Alexander Glazunov

The Rachmaninoff Connection

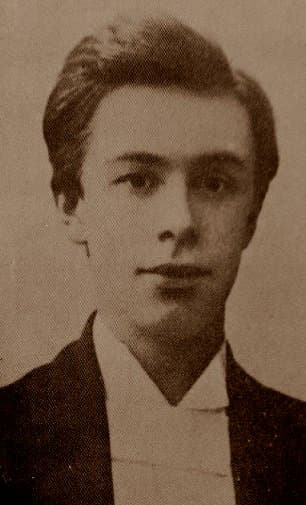

Nikolai Zverev

The Field student Alexander Dubuque also taught Nikolay Zverev, born into an aristocratic family, in 1833. Zverev studied mathematics and physics at Moscow State University, but concurrently, he also took lessons from Dubuque. Zverev inherited a large family fortune and moved to St Petersburg to become a civil servant. Unhappy with his career and urged on by Dubuque, he returned to Moscow to establish his private piano studio. When Nikolai Rubinstein invited him to teach at the Moscow Conservatory, he happily accepted.

Rachmaninoff was only 12 when he auditioned to become Zverev’s student. He was quickly accepted and entered the pianist’s home to receive private piano lessons. Rachmaninoff remembered, “I entered Zverev’s home with a heavy heart and foreboding, having heard tell of his severity and heavy hand, which he had no qualms of resorting to. Indeed, we were able to witness proof of this latter: Zverev had a temper and could launch himself at a person, fists flailing, or hurl some object at the offender. I myself had been the object of his fury on three or four occasions.”

Rachmaninoff continued, “but all other talk of his exacting and severe manner were false. This was a man of rare intellect, generosity and kindness. He commanded a great deal of respect among the best people of his time. Indeed, discipline entered my life.” In May 1886, Zverev took his students to Crimea, where Rachmaninoff continued his studies in hopes of being accepted into Anton Arensky’s class at the Moscow Conservatory.

Sergei Rachmaninoff

It was during this time that Rachmaninoff created his first composition, a now lost Etude in F-sharp Major. He also composed a group of pieces titled “Three Nocturnes,” works regarded as his first serious attempt at writing for the piano. The pieces are not entirely nocturnal in their approach, and they are certainly closer to Field than Chopin. The nocturnes were published only in 1949 without opus number, and while they lack maturity, they are full of suggestions of what was still to come.

First performed in 1892, Rachmaninoff’s C-sharp minor Prelude became his first real hit. In addition, Tchaikovsky tirelessly promoted Rachmaninoff’s talents, and the young composer was exceptionally successful in getting his early compositions into print. Rachmaninoff composed his “Morceaux de salon,” Op. 10, after graduation from the Moscow Conservatory in 1892. A “Nocturne in A minor” opens this collection of piano pieces, and like Field and Chopin, he concentrated on a framework of singing melodies supported by rich harmonies and elaborated by embellishments.

The Scriabin Connection

Georgy Konyus

With Alexander Scriabin we once again find the connection to John Field in the home of Nikolai Zverev. Scriabin had been able to play the piano with both hands by the time he was five, and he was able to reproduce the tunes he heard from passing organ grinders. He received his first formal music lessons from Georgy Konyus, who was not impressed. He writes, “He knew the scales and the tonalities, and with the weak sound of his little fingers which barely carried, he played to me, what exactly, I don’t remember, but it was accurate and satisfactory… he learned pieces quickly, but his performance, it should be remembered, as a result of the shortcomings of his physique, was always ethereal and monotonous.”

Because Scriabin could count on significant family connections, he was able to study with Taneyev, who prepared him for entry to the Moscow Conservatory. And in turn, Taneyev introduced Scriabin to Zverev. Zverev insisted that his students should live in his own house, and Scriabin “learnt not only French and German but also the manners of high society; he was shown great literature and how to drink vodka.”

Scriabin studied among a group of boys of similar age, and that included Rachmaninoff and Goldenweiser. During his study with Zverev, Scriabin performed Schumann’s “Papillons” in the Great Hall of the Charitable Society. That performance showed some obvious talent “despite some inaccuracy.” It was suggested that Scriabin became Zverev’s favourite student, but things changed when his young charge tried his hands at composition. When he dedicated a Nocturne in F-sharp minor to his teacher, later to be published as Op. 5, No. 1, Zverev put his foot down and told him to stop composing.

Alexander Scriabin

From his very beginnings, Scriabin loved the music of Chopin. It’s hardly surprising that we should find a couple of nocturnes in his oeuvre. Stephen Coombs writes, “The Two Nocturnes Op 5, written in 1890, have only the faintest suggestion of reflective ‘night music’ and could as easily have been titled ‘impromptus’ or ‘poems.’ Both pieces display an increased sensuousness and rhythmic freedom together with a more confident and daring use of harmony.”

Scriabin wrote only one more Nocturne, the second of his Two Pieces for Left Hand, Op. 9. Competing against the likes of Rachmaninoff, Hofmann and Lhévinne, Scriabin temporarily lost the full use of his right hand. Eager to prove his ability as a pianist, he turned the Nocturne into a particularly devilish technical exercise. As a pianist wrote, “with Scriabin, the nocturne breaks with the bel canto singing to which it was through John Field, historically linked.” Please join us next time when we take a closer look at the 10 most beautiful Nocturnes by Frédéric Chopin.