It's all about the classical music composers and their works from the last 400 years and much more about music. Hier erfahren Sie alles über die klassischen Komponisten und ihre Meisterwerke der letzten vierhundert Jahre und vieles mehr über Klassische Musik.

Total Pageviews

Monday, September 30, 2024

Spring Waltz (Mariage d'Amour) Chopin - Tuscany 4K

Ennio Morricone: Once Upon a Time in America – Suite, Boian Videnoff .

Ranking classical composers - Tier List

Jules Massenet / Thais / Meditation

3 Heartbreaking piano performance made audience cry, Pressler play Chopin

Nena’s Nocturne: How I discovered my grandmother’s legacy

Anita Villanueva - Philstar.com

Anita Villanueva is the grandchild of the late concert pianist Nena del Rosario Villanueva (1935-2021), the Philippines’ first piano prodigy. Nena, mentored by the famed Isabelle Vengerova, made her Carnegie Hall debut at age 12 in 1947 upon winning a New York Times competition. She was the first Filipino pianist accepted at the Curtis Institute of Music in Philadelphia. She went on to perform in the world’s most prestigious musical venues throughout her career.

Anita writes about a side of her grandma few people knew, how she slowly discovered her legacy in the music world, and her involvement in the Manila Symphony Orchestra’s campaign for Nena’s nomination for National Artist.

Upon hearing my grandmother’s name, a vivid image immediately comes to mind: she is in bed, her hair disheveled, donning one of her many white linen nightgowns. Her spindly fingers are grazing a box of half-eaten See’s Chocolates which she had likely received that same day.

This image is starkly different from the one staring back at me as I sift through photos of her grand performances as the Philippines’ own piano prodigy.

Growing up, my grandma and I shared a very special bond, one separate from her piano accolades. My frequent visits to her house were composed of a strict routine: first, she would mark my height and the date on her white closet doors. Next, I would take on the role of her makeup artist. As she sat at her vanity, I became the painter to her blank canvas of a face. I rummaged through dusty makeup bags and acrylic holders, gathering only the shiniest, most colorful of her expired products.

I then began my work, rubbing shimmery green Chanel eyeshadow on one eyelid and lining her lips with bright red Guerlain lipstick, creating my masterpiece. Once I was finished, I held up a mirror for my grandma to relish her newfound beauty. Every time, without fail, she had lit up with laughter; tears swelling in her eyes as she examined the dance of colors on her face.

Then came the third, most integral part of our routine: the McDonald’s drive-thru. With her make-up on, she and I, immensely proud of my work, would make our way down to her dark green Jaguar. We would drive to the nearest McDonald’s drive-thru, where I ordered a Big Mac with orange juice, and she ordered a caramel sundae with fries. I thought it was the most bizarre thing, watching her dip each fry in her ice cream; she was certainly the only person I had known to do it.

Now, my childhood memories with my grandma, saturated with the smell of mothballs and the sound of her pearl bracelets, remain stowed away, only occasionally revisited. That is until I began to work on what I call the “Grandma Project.”

At first, I was tasked with the seemingly menial job of sorting through large plastic boxes filled with photos, newspaper clippings, and letters. However, the time spent simply sifting through these items became an incredibly transformative experience.

Only when I agreed to help organize her campaign did I discover the depth of this entirely different identity of hers. Growing up, I was always aware of her relationship with piano. Mentioning her name would often trigger the automated response of “the one with the piano right?” However, since she had never once mentioned it herself, I was completely oblivious to the impact she made on the Filipino and international music scenes.

As I look through the various photos of her in huge auditoriums wearing ornate gowns, the letters from former presidents, and newspaper clippings of her at only fourteen, I am becoming acquainted with a different Nena, foreign from the one dipping fries in her caramel sundae.

Though this Nena is completely distinct from the one I so fondly remember, I carry with me the remnants of her identity as I strive to embody the light she sparked in the world.

Sunday, September 29, 2024

David Foster - Earth,Wind&Fire "September" and "After The Love Has Gone"

The Manhattan Transfer - Chanson D'Amour (Live, 1978)

Luciano Pavarotti. 1987. Nessun dorma. Madison Square Garden. New York

Friday, September 27, 2024

Learn EVERY Chord and Chord Symbol - The 7 Systems

Heinrich von Herzogenberg - his music and his life

Born: June 10, 1843 - Graz, Austria

Died: October 9, 1900 - Wiesbaden

The Austrian composer, Heinrich von Herzogenberg, was the son of an Austrian Court official. He received his early education in the humanities at the Gymnasien in Feldkirch (Vorarlberg), Munich, Dresden, and Graz. In 1861, he enrolled at the University of Vienna and began a course of study in law and philosophy. This, however, was short-lived, as in 1862 he left the university to become a composition student of Felix Otto Dessoff, a professor at the Vienna Conservatory. Herzogenberg was to study with Dessoff for the next two years. It was at Dessoff's house that Heinrich first encountered Johannes Brahms. The two soon formed a lifelong friendship, with Herzogenberg devoting himself to the promotion of Brahms' music. Although he seems to have valued Herzogenberg's criticism of his own work, Brahms appears to have never found it in himself to take Herzogenberg seriously as a composer. In 1868, Herzogenberg married Elisabeth von Stockhausen (1847-1892), the daughter of a Hanoverian Court diplomat, and a pianist and composer in her own right. Von Stockhausen too shared a close friendship with Brahms, who seems to have valued von Stockhausen 's insights even more than those of Heinrich. It was through the family's interactions with Brahms that the Herzogenbergs came into contact with some of the most notable figures in German music at that time, including Robert and Clara Schumann.

For a period of four years, the Herzogenbergs lived in Graz, where Heinrich worked as a freelance composer. Then, in 1874, they moved to Leipzig where, with Philipp Spitta and several others, Heinrich was to found the Leipzig Bach-Verein (Bach Society). He became the director of the group in 1875, a position he held for the next ten years. In 1885, Herzogenberg was appointed professor of composition at the Berlin Hochschule für Musik, succeeding Friedrich Kiel. From 1889, in addition to his other teaching duties, he also conducted a master class in composition at the Hochschule. It was also in 1889 that Herzogenberg was elected a member of the Akademie and when he began his tenure as director of the Meisterschule für Komposition in Berlin, a position he was to hold from 1889 to 1892 and again from 1897 to 1900. Elisabeth's death, in 1892, seems to have been a heavy blow to Heinrich, who subsequently buried himself in his work. Later that year, he returned to his position at the Hochschule after an absence due to ill heath, no doubt compounded by his grief over the death of his wife. Herzogenberg continued teaching until 1900 when further ill health forced him to retire; he died shortly afterwards.

As a contemporary of Johannes Brahms, Heinrich von Herzogenberg spent most of his compositional life living in the shadow of Brahms' gigantic stature. Herzogenberg's works represent a great divergence in styles and influences. His output is vast and takes the form of every musical genre with the exception of opera. He wrote many concert works with sacred texts, three oratorios; several choral orchestral works, including two psalms, a mass, a requiem, several motets, and a sacred cantata; two symphonies; chamber music including three string quartets; music for piano and organ; many secular part songs (with and without accompaniment for mixed, men's, and women's choirs); and despite being a lifelong Catholic, many short liturgical works for the Protestant liturgy. In general, his music can be said to exhibit a general Brahmsian surface. The piano works in particular, which were initially influenced by Schumann, as well as the chamber music, are clearly modeled on the music of Brahms. However, beneath these surface commonalties, Herzogenberg's music illustrates not only a variety of other influences, but also the hand of a master composer in his own right. In some of his early works, he was intent upon following the path of the "New German School." A later rejection of the "New German" compositional ideology led the young Herzogenberg to a course of study using as a model the music of J.S. Bach. This interest in early music (especially the music of Bach and Heinrich Schütz) was a trait that was greatly fostered by Spitta and took form in Herzogenberg's church music, especially that of the composer's later years.

Works

While Herzogenberg has tended to be characterized as a mere epigone of Brahms, many of his compositions show little or no overt Brahmsian influence, for example his two string trios Op.27 Nos. 1 & 2, while some early compositions pre-dating his acquaintance with Brahms have features in common with the older composer. He wrote much choral, orchestral, instrumental and chamber music, including eight symphonies (one being a programmatic symphony entitled Odysseus). His early Theme and Variations, op.13, for two pianos (1870) is a notable work in its genre. Important works choral include the cantata Todtenfeier, op.80 (1893) in memory of his wife; Mass in E minor, op.97 (1894) in memory of Spitta and the oratorio Die Geburt Christi, op.90 (1894) with a libretto by Spitta’s brother Friedrich. He wrote a great deal of chamber music: 2 string trios Opp.27 Nos 1 & 2, 5 string quartets Opp.18,42 Nos.1-3, & 63, a string quintet (2 violas) Op.17, 2 piano quartets Opp.75 & 95, 2 piano trios Opp.24 & 36, a trio for piano, oboe & horn, Op.61 and several sonatas for various instruments. Today, the general consensus of critics and scholars is that his contribution in this area is his most important.

The Lesbian Diva and Swordswoman!

Julie d’Aubigny aka Mademoiselle Maupin

by Georg Predota, Interlude

When Julie d’Aubigny, born around 1673, first started her singing career at the Marseille Opéra, she quickly fell in love with a young woman. As you might well imagine, the girl’s family was not particularly amused and shipped their daughter to a convent in Avignon. Julie, undeterred, followed her lover into nun hood. When an elderly nun died, the couple stole the body and placed it in the girl’s cell. Then they set fire to the convent to cover their tracks and escaped! As such behavior was generally frowned upon, Julie was charged with kidnapping, body snatching, arson, and failing to appear before the tribunal. The judges could not quite admit to the possibility of one woman abducting another from a convent, and sentenced her in absentia—as a male—to death by fire! What a remarkable story, but who was Julie d’Aubigny, better known as Mademoiselle Maupin?

Mademoiselle Maupin

Julie’s father, an accomplished swordsman, was a secretary to King Louis XIV’s Master of Horse, Count d’Armangnac. He educated his only daughter alongside the boys training as court pages, and Julie dressed as a boy and was easily the best fencer in the group.

At age 14 she became d’Armagnac’s mistress, and she was also quickly married to Sieur de Maupin. Neither husband nor lover held her fascination for very long, so she ran away with a fencing master named Séranne. They made a living from fencing demonstrations at local fairs, and when a spectator refused to believe that she was a woman, she simply took off her blouse! Once they arrived in Marseille, she joined the opera company run by Pierre Gaultier and appeared under her maiden name. She left Séranne for the young woman, and you already know her convent story. Once again on the run, and dressed as a man, she was insulted by the Count d’Albert and quickly fought a duel. Apparently, she drove her rapier through his shoulder, and when she asked about his health the very next day, they became lovers and lifelong friends!

André Campra

Julie’s dream, however, was to become an opera star. As such, she auditioned for the Paris Opéra, was pardoned for her crimes by the King, and by age 17 became a member of one of the world’s greatest musical companies. She appeared in all of the Opéra’s major productions from 1690 to 1694, and achieved lasting musical fame under her stage name “La Maupin.” And she certainly stayed in the limelight with a number of high-profile off-stage scandals. Dressed in men’s clothing, she kissed a young woman at a court ball and was challenged to a duel by three different noblemen. She easily defeated all three, but since duels had been outlawed, she had to flee to Brussels. There, she became the lover of the Elector of Bavaria—who found her entirely too much to handle—and in Madrid she worked as maid to the Countess Marino. Back in Paris, she became infatuated with the soprano Fanchon Moreau, “tried to hill herself, threatened to blow the Duchess of Luxembourg’s brains out, and ended up in court for attacking her landlord.”

In 1703, La Maupin fell in love with the “most beautiful woman in France,” a certain Madame la Marquise de Florensac. According to contemporary accounts, the two women “lived in perfect harmony for two years.” When de Florensac died of a fever in 1705, La Maupin retired from the opera and sought refuge in a convent. She died in 1707 at the age of 33, and one biographer wrote, “destroyed by an inclination to do evil in the sight of her God, and a fixed intention not to, her body was cast upon the rubbish heap.” Théophile Gautier wrote his celebrated novel Mademoiselle de Maupin in 1835, and a number of opera roles were specifically created for her. Among them was the role of “Clorinde” in André Campra’s Tancrède, premiered in Paris in 1702. The plot is set at the time of the Crusades and depicts the tragic love of the Christian knight Tancrède for the Saracen warrior princess Clorinde. In a drama of misunderstandings and impossible love, he ends up killing her in single combat, when she fights him disguised in the armor of another man.” I don’t know about you, but it’s art imitating life, don’t you think?

Jean-Philippe Rameau (1683-1764): Seven of His Most Beautiful Instrumental Suites

by Georg Predota, Interlude

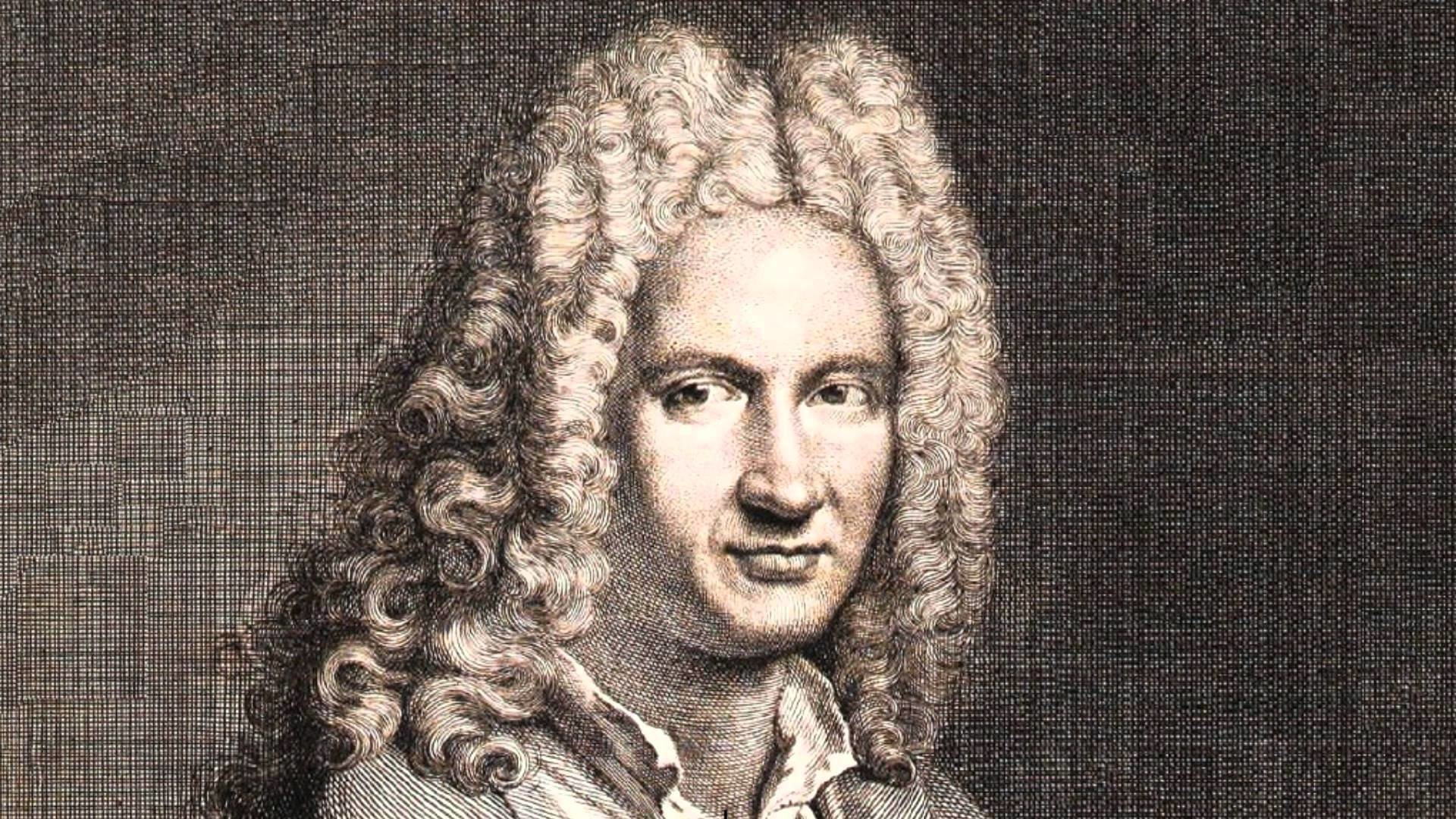

Jean-Philippe Rameau

As a composer, he made important contributions to the cantata, the motet and, specifically, to keyboard music. In terms of his dramatic compositions, Rameau is widely considered, alongside with Lully and Gluck, among the pinnacles of pre-Revolutionary French music. As we celebrate his birthday on 25 September, we thought it might be fun to listen to seven of his most beautiful instrumental suites.

Hippolyte et Aricie

Hippolyte et Aricie

Remarkably, Rameau composed his first opera when he was almost 50, but his catalogue of works eventually grew to more than a hundred separate acts. But what is more, the quality of his dramatic productions established him as one of the greatest opera composers of the Baroque. Following the premier of his first opera, a contemporary composer commented that “there is enough music in it to make ten operas.” Rameau’s music is of the highest quality with great richness and detail, and he was also considered one of great orchestrators of his time.

For his first opera Hippolyte et Aricie of 1733, Rameau selected Abbé Pellegrin as his librettist. The plot is based on Euripides, Seneca and above all Racine’s Phèdre, and it’s a complicated affair. As she believes her husband Theseus to be dead, Phaedra confesses her love for her stepson Hippolytus, who is in love with the young princess Aricia.

When Theseus returns he thinks his son is in love with Phaedra, and asks his father Neptune to send a monster to kill him. Phaedra commits suicide but admits her passion for Hippolytus to Theseus. Hippolytus, who had been believed dead, is saved by Diana and can marry Aricia, while Theseus is condemned never to see his son again.

The dramatic action of the opera is heightened by dance episodes, and these instrumental numbers help Rameau to invent new and more expressive colours. We find a delightful French Overture, and each act features a succession of instrumental pieces. Familiar dances like the rigaudon and the gavotte are interspersed by marches used to introduce characters to the stage, and the Airs unfold in contrasting major/minor or slow/fast pairs.

Zoroastre

Rameau’s Zoroastre costume sketch by Louis Rene Boquet, 1769

Rameau’s Zoroastre of 1749 is supposedly marred by serious defects in the libretto. As a scholar writes, “the conflict of Good and Evil as found in a dualist religion of ancient Persia is weakened by structural flaws and by the introduction of a conventional love element that implausibly involves the great religious Zoroaster himself.” There is plenty of supernatural action as well, and the music is simply awe-inspiring in its power.

Zoroastre, alongside Zaïs, and Les Boréades emerged from the hand of Louis de Cahusac, a playwright for whom the themes of exoticism became more specifically focused on the Middle East. The focus falls on Zoroaster and on the Bactria region, an area annexed by the Persian empire. Although the historical character of Zoroaster had appeared in French opera before, Cahusac was the first author “to make him the central character of an opera.”

The opera was realised using a sophisticated lighting strategy. Act II is bathed in light, while Act IV, which centres on Abramane’s evil incantations, is plunged into darkness. These juxtapositions are clearly heard in the music as the programme to the Overture disclosed. “The first part is a forceful and distressing tableau of Abramane’s barbaric power and the wailing of the people he is oppressing. A gentle calm follows: hope is reborn. The second part is a vivid and joyful picture of the benevolent power of Zoroaster, and of

the happiness of the peoples he has delivered from oppression.”

The remainder of the orchestral suite presents delicate and graceful pieces that include Menuets, and the Airs musically “illustrate the darkness that Cahusac uses to achieve the greatest dramatic and emotional effectiveness during a sacrificial ceremony in which victims are sacrificed using an axe.” And let’s not forget the supernatural scenes which are glorified by dances with music worthy of the best film scores.

Les Paladins

Rameau’s Les Paladins

Rameau’s output touched on virtually all the sub-species of French opera in current use. As we have already seen, he places a heavy emphasis on the tragédie. However, he called Les Paladins a comédie lyrique, suggesting a lighter tone. Les Paladins dates from 1756, and the opera contains number in the Italian style alongside colourful dances and Airs written for the French taste.

In an old castle near a forest, Argie is in love with the paladin Atis. But her guardian Anselme wants to marry her and is holding her and her friend Nérine captive. Nérine tries to charm their jailor Orcan, while Atis and his fellow paladins arrive disguised as pilgrims. When he defeats Orcan, Anselme returns.

Argie confesses her love for Artis to Anselme. He pretends to give his blessing but secretly tells Orcan to kill her. Orcan is reluctant and Nérine, realising Anselme’s plan, again distracts him by pretending she is in love with him. The band of paladins, disguised as demons, give Orcan a beating. While the paladins celebrate their success, Anselme arrives with a group of armed men. Argie and Atis take refuge in the castle, and are saved by the fairy Manto. Manto magically transforms the castle into a Chinese palace and seduces Anselme. Argie can now point to Anselme’s infidelity and he admits defeat. Argie and Atis are reunited and the opera ends with a celebration of their love.

This exciting story elicited some wonderfully lively and colourful musical numbers from Rameau. The overture, with the addition of horns, is a sinfonia in three sections in the Italian style. However, Rameau also included French touches in the slow section. A good many numbers are dances to accompany the on-stage ballet divertissements, and the famous “Air pour les Pagodes” sees the Chinese statues come to life. A spirited Contredanse concludes this wonderful orchestral suite.

Platée

Rameau’s Platée

First performed at Versailles on 31 March 1745, Platée is Rameau’s only comic opera. The occasion for the performance was the wedding of the Dauphin to the Spanish Infanta Maria Teresa. The story is both simple and instantly appealing as it focuses on Platée, a highly unattractive frog-like nymph who inhabits a swamp. She lives under the misapprehension that she is irresistible to men, and that the god Jupiter is in love and wants to marry her.

The entire action is set up in the prologue, including the purpose of the opera, “it is a comedy mocking the folly of man, and the story of a trap set by Jupiter to cure Juno of her jealousy.” Jupiter woos Platée in the form of a donkey, and then an owl. However, the nymph calls on the birds of the marshes and scares Jupiter way.

He returns to declare his love, and as the couple prepares for the wedding, Juno arrives. Furious, she puts an end to the farce and ascends to the heavens with Jupiter. Platée is humiliated and understand that she has been duped, swimming off into the marshes to a chorus of frogs.

The target of that joke might really have been the unfortunate Infanta Maria Teresa, who apparently was not a notable beauty. The music, however, is no joking matter as Rameau’s musical inventiveness and brilliance is heard throughout. Jean-Jacques Rousseau wrote that it was “the most excellent piece of music that has been heard as yet upon our stage.” It features a lively overture and a delicious mixture of airs, choruses and dances that musically portray the intrigue of the roles and characters.

Les fêtes d’Hébé

Rameau’s Les fêtes d’Hébé

Rameau’s opera-ballet Les fêtes d’Hébé, ou Les talens lyriques (The Festivities of Hebe, or The Lyric Talents) was first performed on 21 May 1739, and featured the famous dancer Marie Sallé. The work consists of a prologue and three self-contained acts loosely based around the lyric arts of poetry, music, and dance. The Prologue takes us to Mount Olympus, where Hebe is sexually harassed by Momus. Cupid suggests she should escape with him to the banks of the River Seine to witness festivities celebrating the arts.

The first entrée is dedicated to poetry, and on the island of Lesbos, the love of the two poets Sappho and Alcaeus is endangered by the jealous Thelemus. He persuades King Hymas to banish Alcaeus, but when the kind is hunting, Sappho stages an allegorical play from him, showing him the truth. The king pardons Alcaeus and the lovers reunite. The second entrée is dedicated to music, and in a temple, Iphise, daughter of the King of Sparta, is ready to marry Tyrtaeus, an accomplished musician as well as a warrior. The oracle announces that Iphise must marry the “conqueror of the Messenians,” and Tyrtaeus leads his soldiers into battle. Tyrtaeus is victorious and the act ends with general rejoicing.

The third entrée devoted to dance is set in a scenic grove and includes an ornate garden. The shepherdess Eglé, well known for her skill at dancing, is due to choose a husband. The god Mercury visits her village in disguise and falls in love with her, arousing the jealousy of the shepherd Eurilas. Eglé chooses Mercury and the two celebrate with the help of Terpsichore, the muse of dance, and her followers.

Rameau was a master of writing dance music; it is full of grace and charm, and an internal sense of movements that provides the perfect vehicle for the expression of Baroque dance movements. It is hardly surprising that Les fêtes d’Hébé was one of his most popular pieces ever, performed over 300 times between its premiere and its final appearance in 1777. If you listen carefully, you will hear the orchestrated music of several harpsichord pieces Rameau had published fifteen years earlier.

Castor et Pollux

Castor and Pollux

According to Thomas Christensen, “Castor et Pollux was generally regarded as Rameau’s crowning achievement, at least from the time of its first revival (1754) onwards.” The story features the famous heroes Castor and Pollux. Although they are twin brothers, Pollux is immortal and Castor is mortal. They are both in love with princess Télaïre, but she loves only Castor.

The twins have fought a war against king Lynceus, which resulted in Castor’s death. The opera starts with his funeral rites, and Télaïre expresses her grief to her friend Phébé. Pollux and his Spartans bring the dead body of Lynceus, who was killed in revenge. Pollux confesses his love for Télaïre, but she avoids a reply. In the end, Pollux renounces his immortality so that his mortal twin might be restored to life.

Robert Mealy writes, “Rameau produces some of the most addictively kinetic music written before Stravinsky. No other Baroque dance music seems so clearly to invite its own choreography.” As the famous ballet-master Claude Gardel admitted, “Rameau perceived what the dancers themselves were unaware of; we thus rightly regard him as our first master.”

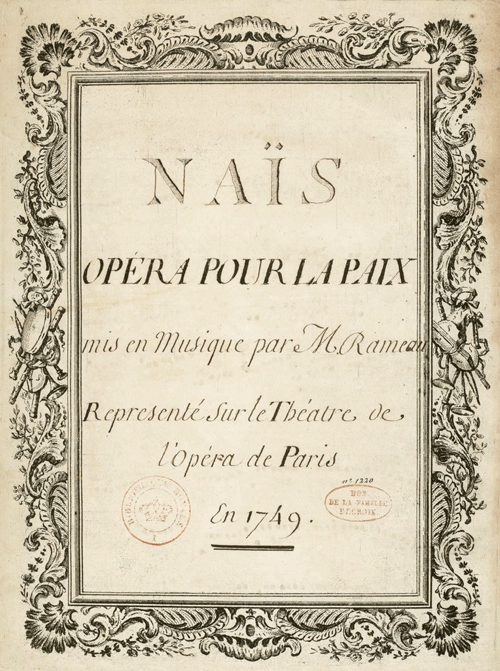

Naïs

Rameau’s Naïs

Rameau composed Naïs on the occasion of the Treat of Aix-la-Chapelle, ending the war of the Austrian Succession. The story tells about Neptune’s love for the nymph Naïs, and he disguises himself as a mortal to try to win her over. Télénus and Astérion are rivals for the affection of Naïs, and her father is a blind soothsayer who warns them to be wary of the sea god. When they attack the disguised Neptune, he drowns them by summoning huge waves. Neptune reveals his identity to Naïs and takes her to his underwater palace, where he turns her into a goddess.

When listening to some of Rameau’s fantastic instrumental suites it is worth noticing the astonishingly inventive orchestral effects created by the most economical means. He draws these special effects from a standard mix of strings and winds, with the colour of the bassoon possibly most striking. A contemporary listener remarked, “Thanks to Rameau, an instrument formerly appreciated only for its force has become pleasant and touching, capable both of pleasing the ear and affecting the heart.”