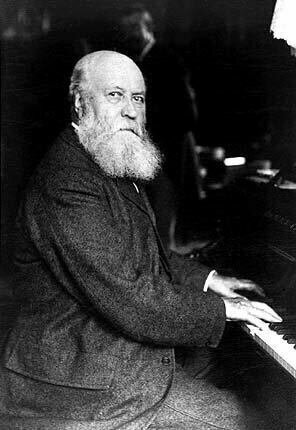

Charles Gounod was born 200 years ago, on 17 June 1818 in Paris. Today we primarily remember him as the composer of the opera Faust and an Ave Maria descant to the first prelude of J.S. Bach’s C-major prelude from the WTC. Yet, during the second half of the 19th century, he was one of the most respected and prolific composers in France. His musical influence on the course of French music was highly significant, but in the fractured post-Wagnerian critical climate towards the end of his life, his reputation took a severe hit. Son of a painter and engraver of considerable talent, Charles exhibited enormous talents in music and the fine arts. Pressured into studying law, Charles decided at age 16 to devote himself to music. Private lessons in counterpoint and harmony with Antoine Reicha prepared Charles for his enrollment at the Paris Conservatoire. Fully devoted to composition, Charles furthered his studies with Halévy and Le Sueur, and he won the Prix de Rome in 1839 with his cantata Fernand.

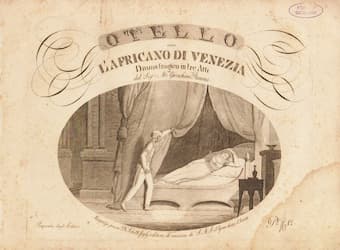

Charles Gounod was born 200 years ago, on 17 June 1818 in Paris. Today we primarily remember him as the composer of the opera Faust and an Ave Maria descant to the first prelude of J.S. Bach’s C-major prelude from the WTC. Yet, during the second half of the 19th century, he was one of the most respected and prolific composers in France. His musical influence on the course of French music was highly significant, but in the fractured post-Wagnerian critical climate towards the end of his life, his reputation took a severe hit. Son of a painter and engraver of considerable talent, Charles exhibited enormous talents in music and the fine arts. Pressured into studying law, Charles decided at age 16 to devote himself to music. Private lessons in counterpoint and harmony with Antoine Reicha prepared Charles for his enrollment at the Paris Conservatoire. Fully devoted to composition, Charles furthered his studies with Halévy and Le Sueur, and he won the Prix de Rome in 1839 with his cantata Fernand. The operatic stage in Rome—primarily populated by Donizetti, Bellini and Mercadante—was of little interest to Gounod. However, coming under the influence of the Dominican preacher Père Lacordaire, Gounod became genuinely fascinated by the music of Palestrina and the cultural legacy of Rome. He also crossed paths with Fanny Mendelssohn, and spent the remainder of his government stipend in Austria and Germany. After meeting with Felix Mendelssohn in Leipzig, Gounod returned to Paris and became music director of the Missions Etrangères church in 1843. He stayed in this position for the better part of four years until he formally enrolled at the seminary of St. Sulpice to begin studies for ordination into the priesthood. In the end, he rather abruptly abandoned his pursuit of the cloth and began to cast his eyes towards the glitzy world of opera.

The operatic stage in Rome—primarily populated by Donizetti, Bellini and Mercadante—was of little interest to Gounod. However, coming under the influence of the Dominican preacher Père Lacordaire, Gounod became genuinely fascinated by the music of Palestrina and the cultural legacy of Rome. He also crossed paths with Fanny Mendelssohn, and spent the remainder of his government stipend in Austria and Germany. After meeting with Felix Mendelssohn in Leipzig, Gounod returned to Paris and became music director of the Missions Etrangères church in 1843. He stayed in this position for the better part of four years until he formally enrolled at the seminary of St. Sulpice to begin studies for ordination into the priesthood. In the end, he rather abruptly abandoned his pursuit of the cloth and began to cast his eyes towards the glitzy world of opera. Gounod was not a household name on the Parisian musical scene, but all that changed when he started to orbit around the mezzo-soprano Pauline Viardot. It was her influence that secured him an unexpected commission at the Opéra for Sapho, with a libretto by Emile Augier. In the event, Sapho was an unmitigated failure at the box office, but the work did receive some critical approval from Hector Berlioz. As such, the Opéra offered him another contract in 1852 to set Eugène Scribe’s libretto La nonne sanglante.

Gounod was not a household name on the Parisian musical scene, but all that changed when he started to orbit around the mezzo-soprano Pauline Viardot. It was her influence that secured him an unexpected commission at the Opéra for Sapho, with a libretto by Emile Augier. In the event, Sapho was an unmitigated failure at the box office, but the work did receive some critical approval from Hector Berlioz. As such, the Opéra offered him another contract in 1852 to set Eugène Scribe’s libretto La nonne sanglante.

Additional projects soon followed but Gounod had no great theatrical success until he hit the jackpot with Faust derived from Goethe. Première on 19 March 1859, the opera was once more praised by Berlioz, but casting problems and a hostile press raised doubt whether Faust would be able to survive. Thanks to the efforts of the publisher Antoine de Choudens, who bought the rights and aggressively promoted the work, Faust exploded onto the European opera stages. Richard Wagner called it a “feeble French travesty of a German monument,” but he could not prevent Gounod’s Faust to become the most frequently staged operas of all time.

Gounod died on 18 October 1893, and although Ravel considered him the “real founder of the mélodie in France,” his music fell rapidly out of fashion. Gounod steadfastly believed in a universal dramatic and spiritual truth, and his refusal to pursue the implications of Wagner’s musical style placed him at odds with writers and critics alike. Debussy quipped, “Gounod, for all his weaknesses, was necessary as his art represents a moment in French sensibility.”

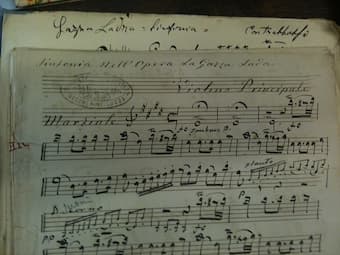

Music, according to Tinctoris, a Renaissance era theorist from the Netherlands, is a ‘nova ars’ – new art – which rejected all that had grown stale from the Middle Ages, and focused instead on infusing it with sweetness and truth (‘suavitas et veritas’). Thinkers and theorists such as Tinctoris joined Italian musicians, such as Gafori, to establish a systematic theory of composition.

Music, according to Tinctoris, a Renaissance era theorist from the Netherlands, is a ‘nova ars’ – new art – which rejected all that had grown stale from the Middle Ages, and focused instead on infusing it with sweetness and truth (‘suavitas et veritas’). Thinkers and theorists such as Tinctoris joined Italian musicians, such as Gafori, to establish a systematic theory of composition. One of the most significant achievements of the time in music and painting is the transition from successive to simultaneous composition. In painting, the classical triangle (just as the tonic triad in music) centers the image on canvas. Painting during the Renaissance era abandoned the medieval superposition of narrative scenes and arrived at the central perspective, at a definite element of form from a single point of sight to the unity of time, action and space. In Botticelli’s painting, the vanishing point is centered on the Holy Family contained in the classical triangle in the center of the painting, which is set into an Italian landscape. The clothing of the Magi and their retinue (Italian courtiers) is in the style of Renaissance Italy, which was intended to demonstrate unity of time, action and space, i.e. order, balance and harmony. The light within the painting is evenly distributed, leaving nothing in the dark, nothing ‘unseen’. Painting found its depth, so that viewers of these paintings could perceive the work almost as if they were looking through a window into three-dimensional space. Painters reinforced this perspective by framing their paintings with replicated window frames to further enhance and emphasize the ‘modern’ three-dimensionality of their work.

One of the most significant achievements of the time in music and painting is the transition from successive to simultaneous composition. In painting, the classical triangle (just as the tonic triad in music) centers the image on canvas. Painting during the Renaissance era abandoned the medieval superposition of narrative scenes and arrived at the central perspective, at a definite element of form from a single point of sight to the unity of time, action and space. In Botticelli’s painting, the vanishing point is centered on the Holy Family contained in the classical triangle in the center of the painting, which is set into an Italian landscape. The clothing of the Magi and their retinue (Italian courtiers) is in the style of Renaissance Italy, which was intended to demonstrate unity of time, action and space, i.e. order, balance and harmony. The light within the painting is evenly distributed, leaving nothing in the dark, nothing ‘unseen’. Painting found its depth, so that viewers of these paintings could perceive the work almost as if they were looking through a window into three-dimensional space. Painters reinforced this perspective by framing their paintings with replicated window frames to further enhance and emphasize the ‘modern’ three-dimensionality of their work.