The Piano: A History in 100 Pieces by Susan Tomes

It was perhaps inevitable that pianist and writer Susan Tomes would turn her attention eventually to the extraordinarily broad repertoire of the piano – her instrument, and mine, and that of countless others, both professional and amateur players. While her previous books have been concerned with the myriad aspects of being a pianist – from performing, recording and teaching, concert preparation, etiquette and attire, and audiences to the daily exigencies of practising and rehearsing – her latest volume, The Piano: A History in 100 Pieces is concerned with repertoire and how the piano’s development and capabilities have influenced how composers write for it.

This comprehensive book uses specific pieces from the repertoire – some very well known, others less so – to illustrate the piano’s history and illuminate its development, from the moment in the early 18th century when it began to supplant the harpsichord as the keyboard instrument du jour to the modern piano as we know it today.

From the outset, the piano offered composers a greater varieties of colours, effects and timbres, and so their music reflected the piano’s capabilities and range, its potential for songful lyricism or an orchestral richness of sound, amply demonstrated in the piano sonatas of Haydn, Mozart and Beethoven, for example, the song accompaniments of Schubert, or Chopin‘s Nocturnes with their bel canto melodies.

The book begins in “pre-history”, with music written for the harpsichord, the most famous of which is Bach’s Goldberg Variations, a pinnacle of the repertoire and a work which continues to fascinate performers, audiences and commentators alike. Bach’s Italian Concerto also features in this section, together with works by Domenico Scarlatti and C.P.E. Bach – all works which can be played and enjoyed equally on harpsichord or piano.

Susan Tomes

We then move from the harpsichord to the fortepiano and thence to the piano itself, in its earliest iteration, a much smaller instrument physically, but already one with far greater range and tonal projection than the harpsichord or fortepiano, as is clear from the music of Haydn and Mozart. One of the pieces explored in this chapter is Haydn’s Variations in f minor, Un piccolo divertimento, Hob. XVII: 6, a work of profound expression, which foreshadows Schubert, and pianistic breadth. Unsurprisingly, Haydn’s great E-flat major Sonata, Hob. XVI:52 is also covered in detail in this chapter, a work which utilises the capabilities of the piano to their fullest extent in a work of great character, texture and variety.

But as these early chapters reveal, this book is not simply a chronology of the piano, not by any means; but rather a detailed exploration of some of the greatest music composed for the instrument as well as lesser-known gems, written from the authoritative standpoint of someone who knows both instrument and repertoire intimately. And it comes right up to date with a chapter focusing on music by living composer Arvo Pärt, Philip Glass, Judith Weir and Thomas Adès.

Susan Tomes writes with a lucid eloquence founded on knowledge, experience and, above all, affection for the piano, which shines through every paragraph. She not only offers the reader important analysis, contextual details and performance notes for each work, but also demonstrates a deep understanding of what it feels like to actually play this music, the sensation of the notes “under the hands”, how it sparks the imagination and provokes emotions, and the experience of learning and shaping it to bring it to life in concert – fascinating insights which take the reader “beyond the notes”, as it were. Thus, the book acts as both a historical survey and a primer for those seeking more detailed information about specific works, with guidance on performance practice and interpretation, drawn from Tomes’ own experience as a soloist, chamber musician and teacher.

The range of pieces explored in the book reflects the vast breadth of the piano’s repertoire, and Tomes is the perfect guide through this almost overwhelming embarrassment of musical riches.

Nor does she confine herself only to the solo repertoire. Concerti and chamber music also feature heavily, from, for example, Schubert’s much-loved ‘Trout’ Quintet to Rachmaninoff‘s Piano Concerto No. 3, to demonstrate the piano’s importance in these genres and how it interacts with and complements other instruments. Jazz is also covered, while the final chapter explores where the piano and its repertoire might be heading, and how we as listeners, and players, might open our ears and minds to a different range of music, presented in less traditional performance settings.

Robert Schumann: Piano Concerto in A Minor, Op. 54 – I. Allegro affettuoso (Florian Uhlig, piano; German Radio Saarbrücken-Kaiserslautern Philharmonic Orchestra; Christoph Poppen, cond.)

This comprehensive, informative and highly readable celebration of the piano and its literature is a must-read for pianophiles and music lovers. With its wealth of analysis and contextual information it is also a significant resource for those who teach and play the piano, a book to keep close by the instrument to refer to, dip into, and cherish.

The Piano: A History in 100 Pieces is published by Yale University Press

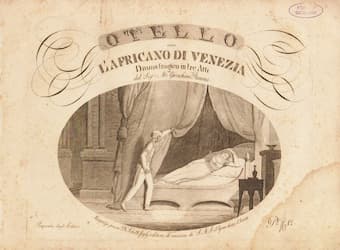

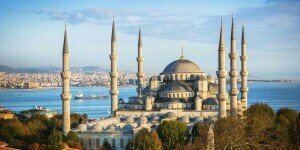

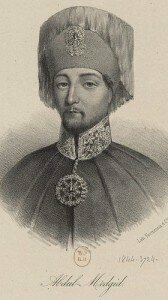

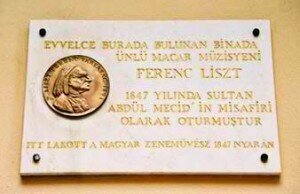

Liszt also gave a number of public concerts, including a musical matinee on 18 June at the Franchini Mansion at Buyukdere. Further private and public concerts were held at the Fethi Pasha Mansion and the Russian Embassy at Pera on 28 June. During this concert, “Liszt saw the panorama of Istanbul from the window and got really excited of seeing the east and the west at the same time. He even thought that he could seen Mount Olympus in the distance.” During his five-week stay, Giuseppe Donizetti hosted Liszt and he arranged accommodations for him at the home of the piano manufacturer Alexander Kommendinger. Donizetti had previously composed two marches for the Sultan, and at Liszt’s request, Donizetti gave him his compositions. “Liszt was in my house,” he writes. “He has just left. He wanted the notes of the two marches I composed for the Sultan. He said he was going to work them into variations sets.” Liszt first played the variations during concerts at Buyukdere on 14 and 15 June. Liszt eventually wrote out the manuscript and gave it to the Austrian ambassador, who passed it to the Minister of Foreign Affairs, who in turn presented it to the Sultan. In return, Liszt received the already mentioned enamel box studded with diamonds. Additionally, the Sultan handed Liszt a special seal, with the name of the composer written in Arabic alphabet with Turkish letters, and we do know that Liszt used it to seal a number of his letters. As it turns out, Istanbul delivered the perfect setting for Liszt to say goodbye to his life as a traveling virtuoso.

Liszt also gave a number of public concerts, including a musical matinee on 18 June at the Franchini Mansion at Buyukdere. Further private and public concerts were held at the Fethi Pasha Mansion and the Russian Embassy at Pera on 28 June. During this concert, “Liszt saw the panorama of Istanbul from the window and got really excited of seeing the east and the west at the same time. He even thought that he could seen Mount Olympus in the distance.” During his five-week stay, Giuseppe Donizetti hosted Liszt and he arranged accommodations for him at the home of the piano manufacturer Alexander Kommendinger. Donizetti had previously composed two marches for the Sultan, and at Liszt’s request, Donizetti gave him his compositions. “Liszt was in my house,” he writes. “He has just left. He wanted the notes of the two marches I composed for the Sultan. He said he was going to work them into variations sets.” Liszt first played the variations during concerts at Buyukdere on 14 and 15 June. Liszt eventually wrote out the manuscript and gave it to the Austrian ambassador, who passed it to the Minister of Foreign Affairs, who in turn presented it to the Sultan. In return, Liszt received the already mentioned enamel box studded with diamonds. Additionally, the Sultan handed Liszt a special seal, with the name of the composer written in Arabic alphabet with Turkish letters, and we do know that Liszt used it to seal a number of his letters. As it turns out, Istanbul delivered the perfect setting for Liszt to say goodbye to his life as a traveling virtuoso.