It's all about the classical music composers and their works from the last 400 years and much more about music. Hier erfahren Sie alles über die klassischen Komponisten und ihre Meisterwerke der letzten vierhundert Jahre und vieles mehr über Klassische Musik.

Popular Posts

-

by Hermione Lai It’s not really common knowledge, but Georges Bizet was an absolutely brilliant pianist. He entered the class of Antoin...

-

by M aureen Buja With its full title, La mer, trois esquisses symphoniques pour orchestre (The sea, three symphonic sketches for orchest...

-

By Georg Predota “Blind Tom,” as he was generally known, was born into slavery in Columbus, Georgia in 1848. He was sold with his family du...

-

by Emily E. Hogstad June 7th, 2025 The great composers left behind more than just great music: they also left behind advice for their fe...

-

774,844 views May 29, 2024 #pierobarone #ignazioboschetto #tuttiperuno Social • Instagram: @ignazioboschetto.italy • Tiktok: @ignazi...

-

182,711 views Feb 22, 2025 #WendyKokkelkoren #Goosebumps #Ballads 00:00 - 05:00 Hallelujah 05:01 - 09:38 I Will Always Love You 09...

-

63,350,847 views Oct 25, 2009 #IlDivo #Adagio #Colosseum Adagio “Adagio” is a vocal arrangement of an original piece for strings and ...

-

24,755 views Mar 23, 2017 Mozart - Piano Concerto No. 18 in B-flat major, K. 456 Rachmaninov Hall Of Moscow Conservatory Moscow Youth Cham...

-

Join the cast of Les Misérables' 25th anniversary concert as we take a look at the first & last songs from the live musical with our...

Übersetzerdienste - Translation Services

Total Pageviews

Friday, May 9, 2025

Mantovani And His Orchestra - And I Love You So, The Very Thought Of

Yunchan Lim piano - Beethoven Piano Concerto No 3 from 2022 Yeulmaru New...

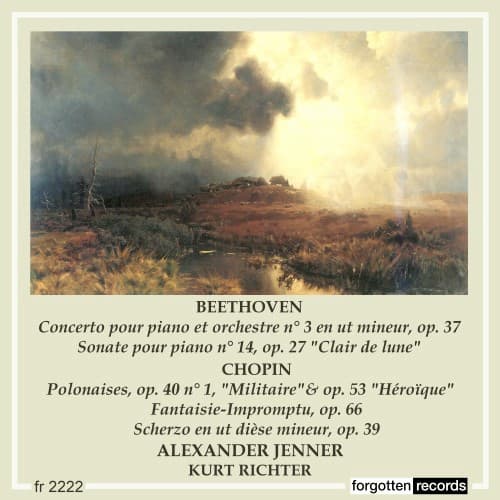

Finding a New Creative Path: Beethoven’s Third Piano Concerto

by Maureen Buja

When he finally arrived in Vienna as a permanent resident in 1795, Beethoven fit into an interesting hiatus in the city’s music life. Mozart‘s recent death left a place open for a daring piano virtuoso and composer. In his first 10 years in the city, Beethoven wrote 20 of his 32 piano sonatas and 3 of his piano concertos—who better to show off his skills than himself?

Joseph Willibrord Mähler: Ludwig van Beethoven, ca 1804–1805 (Vienna Museum)

Completed in 1803 and revised in 1804, Beethoven’s Third Piano Concerto started with sketches as far back as 1796, and the first and second movements were completed around 1800. It was given its premiere with the composer at the keyboard on 5 April 1803 in a concert that included the Second Symphony and Christ on the Mount of Olives, his oratorio.

Beethoven was starting to have problems with his hearing as he approached this concerto, and this set him on his new creative path. Music, for him, became a dynamic process, rather than the filling in of architectural forms. One example of this can be seen in his 3rd Symphony, the Eroica, where the first theme isn’t as it is first stated but comes to define its form through the progress of the first movement.

The 3rd Piano Concerto falls between this new compositional method of the Eroica and his earlier Viennese style, when he was more concerned with establishing his name and credentials as a composer and performer.

If we look at just the first movement, we seem to be starting with a theme more intended for a symphonic movement, rather than a concerto movement. The orchestra gives the first statement of the theme, and Beethoven uses the orchestra to create motivic blocks that can be moved around as necessary. He plays with the different registers of the orchestra and inserts his ‘heavy beats on light places’ to play with the rhythms. His focus, however, is the soloist, and the piano is given a brilliant placement that foreshadows much of his later piano writing.

The repeat of the opening gives him the opportunity to play with the opening theme, but the following development is kept short. It’s the final section, with the Coda where the theme seems to really blossom and show its potential.

There’s so much in this work that gives us an indication of the unique way that Beethoven will progress – always challenging the norm, pressing forward with new ideas, and rethinking the usual to create the unusual.

This recording was made in 1958, with Alexander Jenner as soloist under Kurt Richter leading the Symphony Orchestra of the Volksoper Vienna.

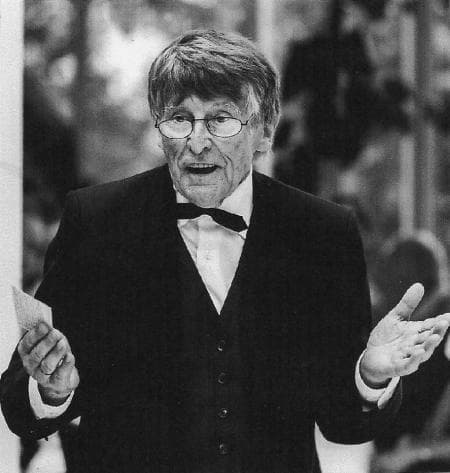

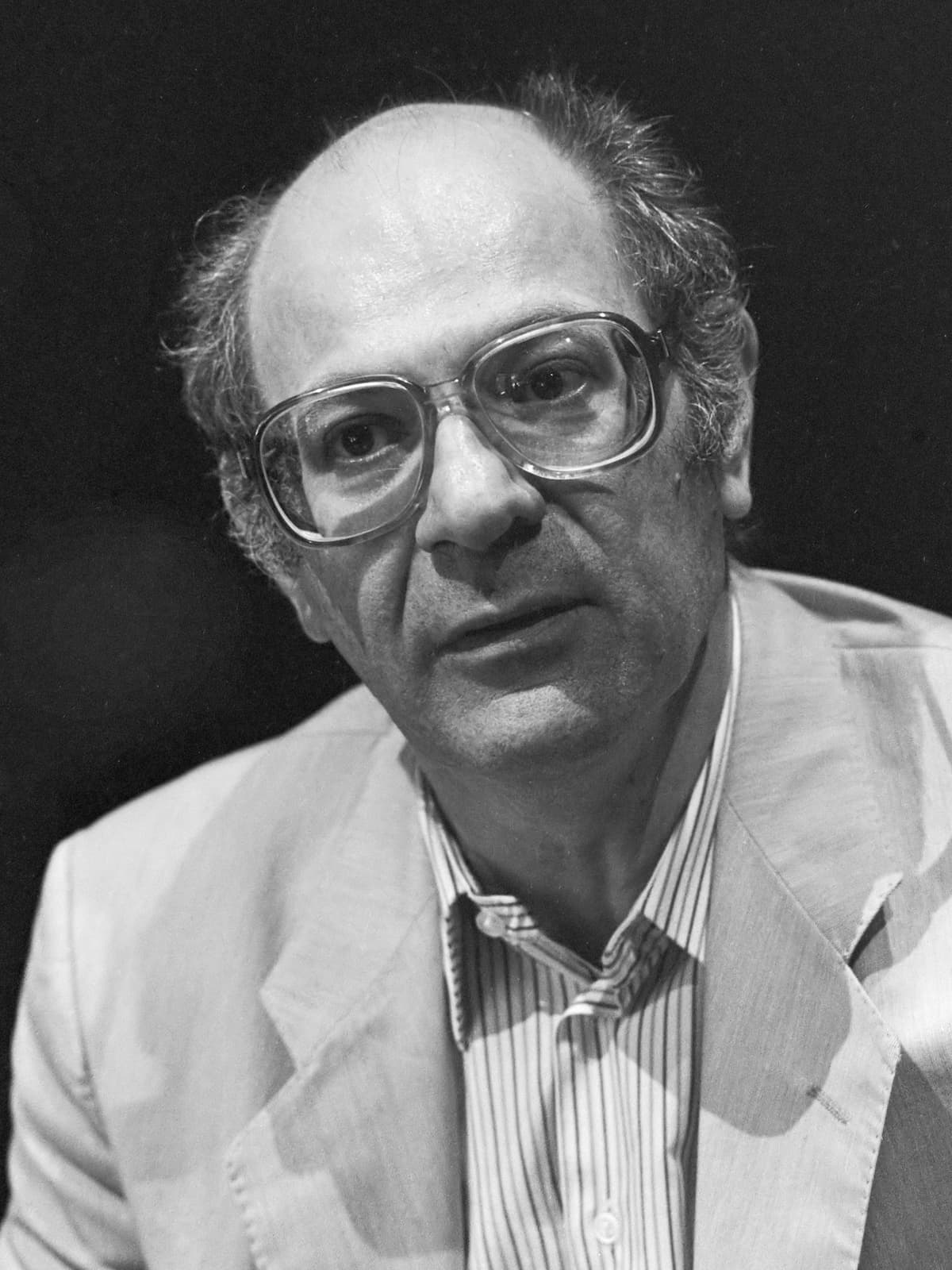

Alexander Jenner

Alexander Jenner (b. 1929) studied in Vienna and, upon graduation in 1949, was awarded the ‘Bösendorfer-Preisflügel’, a grand piano given to the best student of that year graduating from the Vienna State Academy of Music. In 1957, by unanimous jury vote, he was awarded first prize in the Rio de Janeiro Contest for Pianists. As a performer, in addition to the classics, he was active in the promotion of modern music, becoming the first Austrian pianist to perform George Gershwin’s two great piano works, the Rhapsody in Blue and the Concerto in F in 1951; he also gave the premiere of Stravinsky’s Petrouchka for solo piano.

Kurt Dietmar Richter

Kurt Dietmar Richter was a German composer and conductor (1931–2019) who lived in Pilzen, Bohemia, now part of the Czech Republic. He received his musical training in Erfurt, where he fell under the influence of Paul Hindemith and, throughout his life, continued to promote modern music. In 1990, he founded the Berlin artist initiative die neue brücke.

Performed by

Alexander Jenner

Kurt Richter

Symphony Orchestra of the Volksoper Vienna

Recorded in 1958

Official Website

On This Day 9 May: Anne Sofie von Otter Was Born

by Georg Predota

Born in Stockholm, Sweden, on 9 May 1955, Anne Sofie von Otter is one of the finest singers of her generation. Internationally recognised as a concert and recital singer of exceptional gifts, von Otter has built an incomparable catalogue of recordings. Her ever-evolving repertoire and versatility have seen her branch out into the world of opera, jazz, rock, and pop songs.

Beatles and Cat Stevens

Anne Sofie von Otter

Her father Göran von Otter was a Swedish diplomat in Berlin during World War II, and Anne Sofie grew up in Bonn, London, and Stockholm. She knew absolutely nothing about classical music and cared even less. “I couldn’t tell the difference between a tenor or a bass, or between Bach and Mahler,” she explained in an interview. Growing up in comfortable surroundings, von Otter took obligatory piano lessons, but she was really into pop and rock music.

She loved the Beatles above all, but also Cat Stevens, Judy Collins and Crosby, Stills and Nash. “It was the nice tidy pop,” she greatly enjoyed. “The Rolling Stones were not for me.” Later, a friend introduced her to fusion jazz, which she thought was very daring at the time. However, she really loved the ballet, especially the Tchaikovsky ballets she attended in Stockholm and later in London, where her father was the Swedish Consul General for five years.

Dashing Music Teacher

Von Otter’s biggest dream as a child was to become a ballerina, and she did take dance classes.

As she once disclosed, “I was terribly disappointed when I realized that I could not do it.” Singing wasn’t even on the radar until her last two years of high school in Sweden when a dashing young music teacher took over the chorus, “and I just had to sign up.” She didn’t know anything about singing and had no experience of going to the opera. “It took me a while to understand,” she remembers, “that I had a gift for singing.”

However, as von Otter explained in an interview, “I always wanted to use the voice in a natural way, so classical singing, with all that it implies, for me was very strange. I didn’t like vibrato. It was horrifying. Whenever I sang in my teens it was with my natural voice.” Von Otter became a dedicated choir singer, learning to read music and different styles, from Baroque to Contemporary. She certainly never had any fantasies about becoming an opera singer at all, as she was “very self-conscious, nervous, and very shy.”

Studying Under Vera Rózsa

Vera Rózsa

Von Otter sang in a number of choruses, always in the soprano section. “But it was killing my voice,” she said. “I wanted to be a soprano, and it was hurting, so what could I do?” She started taking singing lessons and her singing teacher told her, “You are not a soprano, you are a mezzo.” She won a place at the Guildhall School of Music and Drama in London and studied with the legendary Hungarian teacher, Vera Rózsa. Her insight into a singer’s voice and technique was famous, and after listening for just a couple of bars, she immediately knew what exercise was needed.

For von Otter, the contrast between Rózsa’s high-energy and the more laid-back approach of her Swedish singing teachers was striking. Rózsa quickly undid some of the damage to von Otter’s voice, and she instilled in her the mantra that a good singer needs, “artistic temperament, concentration, dramatic ability, personality, good taste, and total devotion to the profession. An artist needs a heart on fire and a brain on ice.”

Shift to Opera

Rózsa organised a repertoire of operatic roles for von Otter and suggested that she audition for a position in an opera house. Von Otter was not enthusiastic, as “I didn’t want to be a soloist. I wanted to sing and I didn’t mind people hearing my voice individually but I would rather be up the back of a choir than have them look at me because that was embarrassing.” She certainly did not want to be in the spotlight, and the transformation to the stage did not come naturally.

At that time, von Otter still made a living from singing in a number of choirs in Stockholm, including the cathedral choir, the radio choir, and the Bach choir, and she made enough money to survive. She never dreamt of standing on the operatic stage, but her manager and agent, a little against her will, urged her to audition, and she was quickly snapped up by Basel Opera, making her debut in 1983. “I got my first job,” she recalled, “and indeed it was good for me. It developed me as a performer and my understanding of what I was singing about.”

Forbidden Harmonies: Composers Whose Music Was Once Banned

by Fanny Po Sim Head

Throughout history, music has been both a reflection of and a response to societal and political climates. Under authoritarian regimes, art—particularly music—has often been a target for censorship. Whether deemed politically subversive, ideologically incorrect, or culturally inappropriate, certain works were banned, silenced, or suppressed in an attempt to control the narratives and voices that music can powerfully communicate. This article explores the lives and works of composers whose music faced censorship, showcasing the deep intersection between art and politics and the resilience of composers who faced suppression under totalitarian regimes.

Alban Berg (1885–1935)

Alban Berg, 1920s

Alban Berg was an Austrian composer known for emotionally intense music bridging late Romanticism and modernism. A key figure in the Second Viennese School, Berg studied under Arnold Schoenberg and created atonal music that expanded emotional and structural expression. Despite his non-Jewish status, his connection to Schoenberg and atonality made him a target of the Nazi regime’s campaign against “degenerate music.”

Berg’s opera Wozzeck, premiered in 1925, was groundbreaking for its atonality and acclaimed. However, with the Nazi rise in the early 1930s, his works were labeled “degenerate” and banned in Nazi-controlled areas. This suppression affected his later opera Lulu and the Lulu Suite, which also faced condemnation. The Lulu Suite premiered in Berlin in 1934 but met resistance, resulting in conductor Erich Kleiber’s resignation in protest. By 1935, all performances of Berg’s music were prohibited in Nazi Germany, and although his Violin Concerto premiered posthumously in 1936, it reflected the peak of censorship. While not openly denounced like some composers, Berg’s music remained silenced during a highly oppressive period of the 20th century.

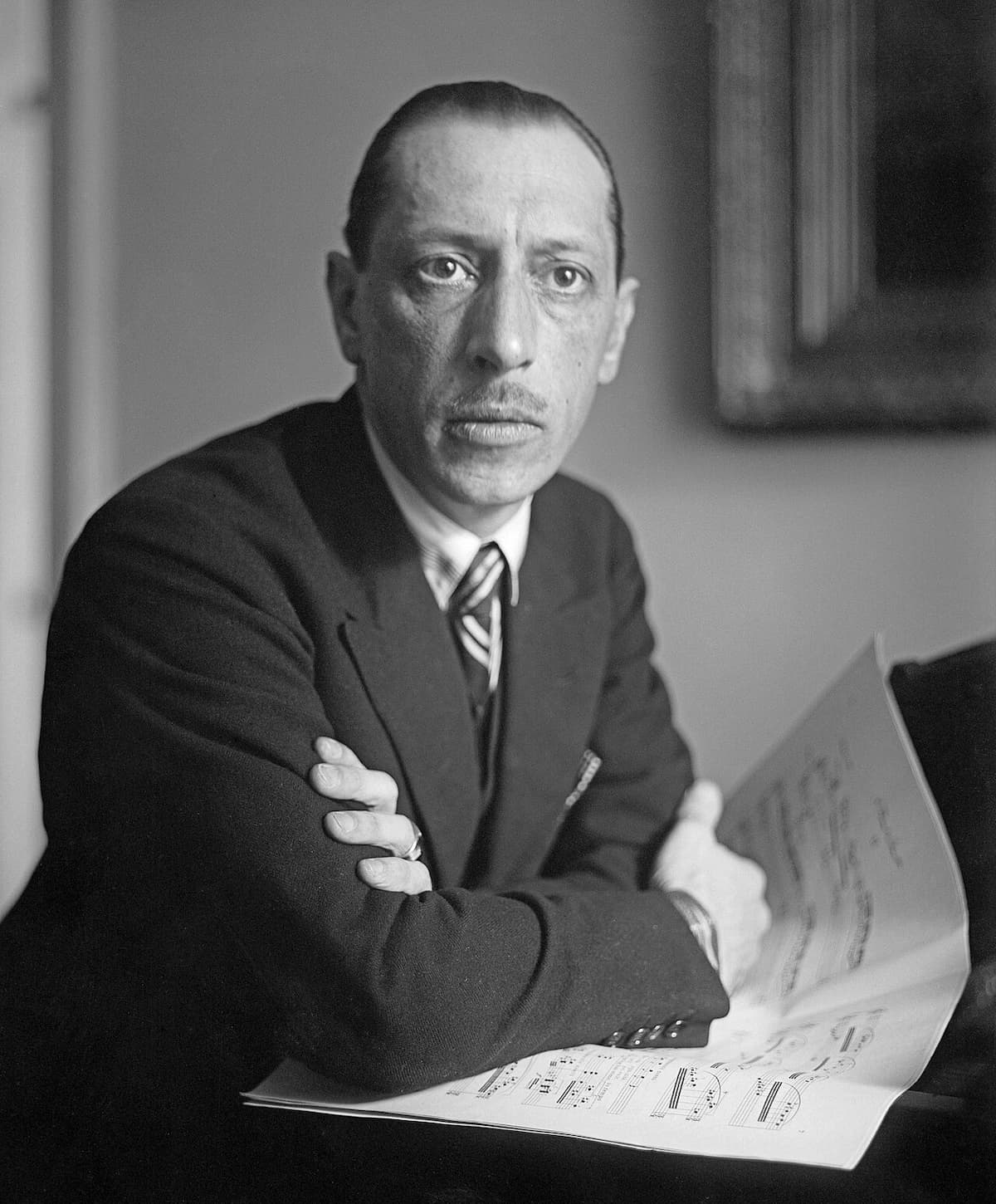

Igor Stravinsky (1882–1971)

Igor Stravinsky

Igor Stravinsky, one of the most influential composers of the 20th century, is best known for his revolutionary ballets The Firebird, Petrushka, and The Rite of Spring, which shattered conventional music traditions. However, Stravinsky’s avant-garde approach did not endear him to all regimes, particularly those with ideologically driven artistic policies. His music was banned and suppressed in the Soviet Union, particularly after the 1917 revolution, when he criticized the regime and emigrated. Stravinsky, a celebrated figure in Russia, soon found himself labeled an enemy of the state.

In Soviet Russia, much of Stravinsky’s music was denounced as bourgeois and formalist. His early works, including The Rite of Spring, were deemed decadent and inaccessible by the Soviet authorities, leading to their prohibition. It was not until the 1960s, after Stravinsky’s return to Russia under tight surveillance, that some of his music was cautiously reintroduced. However, for most of his life, Stravinsky’s works remained largely banned in his home country, silenced by a regime that feared the influence of Western, modernist thought.

Dmitri Shostakovich (1906–1975)

Dmitry Shostakovich, 1942 (Red Star newspaper, No. 86 (5150) from 12 April 1942)

Dmitri Shostakovich, one of the greatest composers of the Soviet Union, became a symbol of artistic survival under the oppressive policies of Joseph Stalin. Shostakovich’s music, which often oscillated between personal expression and forced compliance, faced constant scrutiny. His opera Lady Macbeth of Mtsensk District (1934), initially acclaimed, was suddenly criticised by the Soviet regime in 1936 after a scathing review in Pravda, labeled as “muddle instead of music.” This criticism led to the withdrawal of several of his works and years of self-censorship as he navigated the complex relationship between artistic freedom and state control.

Shostakovich’s Fourth Symphony was suppressed before its premiere, while other works such as the Eighth Symphony and From Jewish Folk Poetry were banned due to their perceived political implications and pessimism. Despite moments of official rehabilitation, Shostakovich’s compositions remained under the threat of censorship for most of his life, reflecting the constant tension between artistic expression and political pressure.

Ding Shande (1911–1995)

Ding Shande © sin80.com

Ding Shande, a prominent Chinese composer, faced significant challenges during China’s Cultural Revolution (1966–1976), a period marked by extreme censorship and the suppression of anything deemed “bourgeois.” Western classical music was viewed as a symbol of imperialism, and many of Ding’s works—rooted in Western tradition—were suppressed during this era. His Long March Symphony, a composition that celebrated the Red Army’s historic journey, was initially well-received but later faced suppression as China’s political climate turned against any perceived foreign influence.

While Ding’s music was not banned in the same way as Western composers, his ability to compose and perform freely was restricted under the Cultural Revolution’s stifling ideological control.

Grażyna Bacewicz (1909–1969)

Grażyna Bacewicz

Polish composer Grażyna Bacewicz is widely regarded as one of Poland’s most accomplished musicians. During the Nazi occupation, she endured the harsh conditions imposed on Polish artists but continued to create, often in secret. Bacewicz, along with other musicians, performed clandestine concerts to keep music alive during the war. After the occupation, she faced more formal repression during the Communist regime, which had a distaste for modernist styles. Her works, particularly her String Quartet No. 2, were composed and performed in defiance of the occupying forces.

Bacewicz’s music became a symbol of resilience in the face of oppression, demonstrating the power of music to both resist and survive under harsh conditions.

Witold Lutosławski (1913–1994)

Witold Lutosławski

Witold Lutosławski was another prominent Polish composer whose music faced suppression under the Communist regime in Poland. Lutosławski’s compositions, particularly his First Symphony, were labeled “formalistic” and banned by authorities for being too complex and nonconformist. His music, which often challenged the conventions of Soviet-approved style, was seen as a threat to the ideological conformity that the regime sought to maintain. Despite these challenges, Lutosławski’s music gained recognition on the international stage, and he became a leading figure in 20th-century music.

Lutosławski’s works, once banned at home, have since become staples of the classical repertoire, symbolising the triumph of artistic freedom over political oppression.

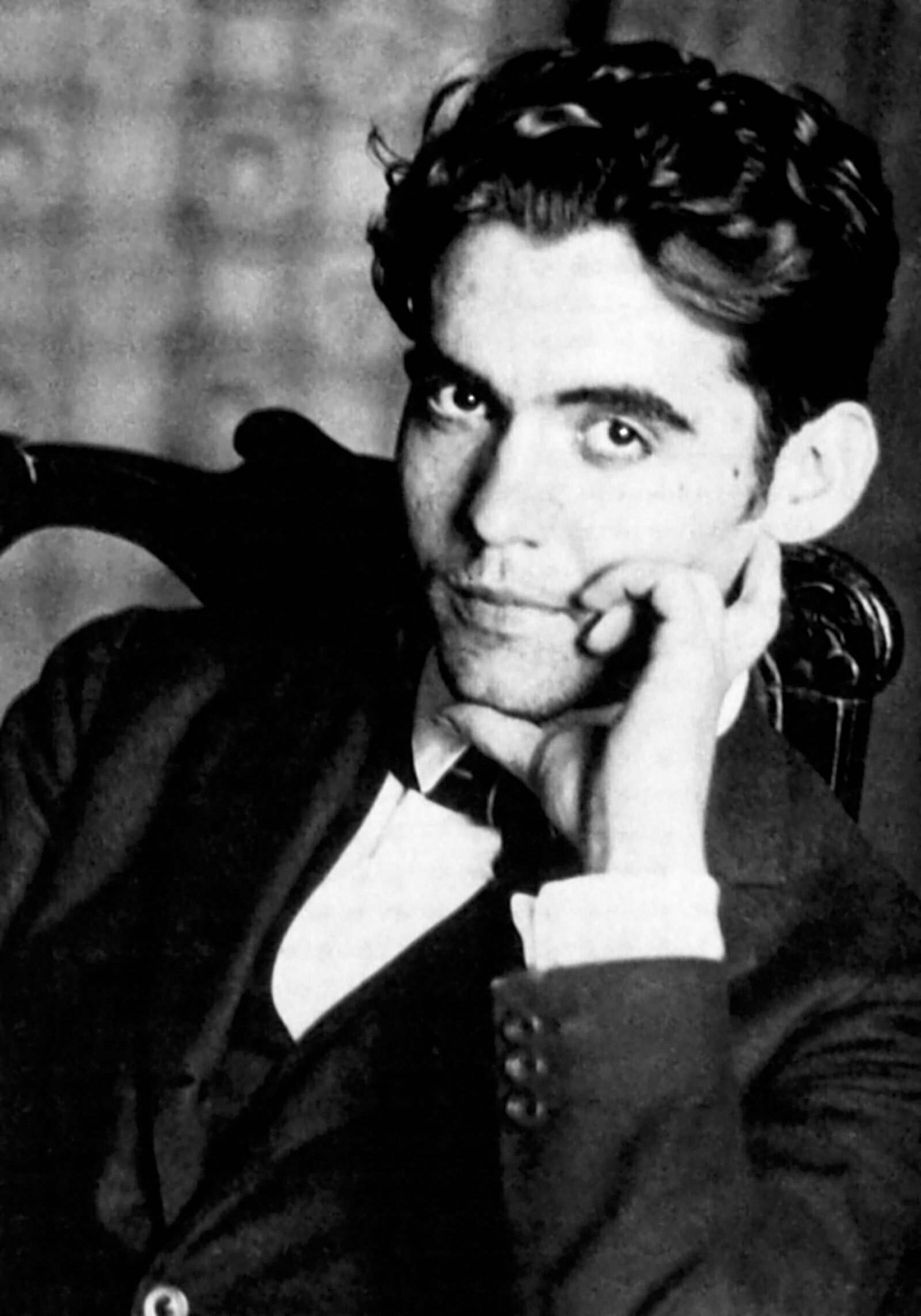

Federico García Lorca (1898–1936)

Federico García Lorca

Federico García Lorca, a celebrated Spanish poet and playwright, also made significant contributions to Spanish music, particularly through his collection and arrangement of traditional Spanish folk songs. His Colección de canciones populares españolas (1931), created in collaboration with the singer La Argentinita, highlighted the beauty of Spanish folk traditions. However, due to Lorca’s political beliefs and personal identity—he was openly gay and a Republican during Spain’s turbulent years—his works faced severe censorship under Franco’s dictatorship.

After his tragic assassination in 1936, many of Lorca’s works were banned, and his folk song collection was suppressed as part of the Franco regime’s effort to stifle cultural and political dissent. It wasn’t until after Franco’s death in 1975 that Lorca’s music was revived and began to regain its place in Spain’s cultural landscape.

Paul Hindemith (1895–1963)

Paul Hindemith, 1923

Paul Hindemith, a German composer and violist, found himself on the receiving end of Nazi censorship. His music, which combined modernist and neoclassical elements, was initially accepted but soon became targeted due to its perceived lack of alignment with Nazi ideals. Hindemith’s opera Mathis der Maler, which explored the role of the artist during political strife, sparked controversy, and by 1936, his works were banned in Germany. Faced with increasing persecution, Hindemith left Germany and eventually settled in the United States, where he continued his compositional career.

Despite his international success, Hindemith’s legacy in his home country was temporarily erased due to the oppressive political climate.

Mauricio Kagel (1931–2008)

Mauricio Kagel

Mauricio Kagel, an Argentine-born composer, became known for his experimental and theatrical approach to music. Kagel’s works often defied conventional musical boundaries, using irony and satire to critique societal norms and political regimes. While living in Germany, Kagel’s compositions like Ludwig van (1970) and Staatstheater (1971) were controversial for their audacity and critiques of cultural institutions. Staatstheater, in particular, faced significant resistance and even required police protection for its premiere. Although Kagel’s music was not officially banned, his works were suppressed in politically conservative environments, including during Argentina’s military dictatorship.

Kagel’s contributions to experimental music serve as a testament to the power of art to resist and critique authoritarian power structures.

Gilberto Mendes (1922–2016)

Gilberto Mendes © Wikipedia

Gilberto Mendes, a Brazilian composer known for his avant-garde approach and political activism, also faced censorship, especially during Brazil’s military dictatorship (1964–1985). While his music was not formally banned, works like Motet em Ré Menor and Santos Football Music were unofficially suppressed due to their political subtext. Mendes used his compositions to criticize societal and political issues, and this led to his music being withdrawn from festivals or omitted from broadcasts. Despite these challenges, Mendes remained a steadfast advocate for artistic freedom, helping to redefine Brazilian music in a time of political repression.

The experiences of these composers reflect the complex and often painful intersection of art, politics, and censorship. Music has long been a powerful force for both expression and resistance. Through their work, composers like Berg, Stravinsky, Shostakovich, and others not only endured suppression but also used their art as a form of defiance. The censorship of their music serves as a reminder of the enduring power of music to transcend oppressive regimes, offering hope, resistance, and a lasting legacy of resilience in the face of adversity.

Global Giggle Fest World Laughter Day Unleashes Hilarity

by Hermione Lai

On the first Sunday in May, we celebrate World Laughter Day. It all started in a park in Mumbai in 1998 when Dr. Madan Kataria gathered hundreds of people in a laughter yoga movement.

It started with some fake-laughing until the giggles turned real. It was gloriously absurd as strangers cackled like hyenas, some wiping tears of laughter, all because someone pretended to laugh at a non-existent joke.

Laughing is highly infectious, and moments of organised silliness remind us that laughter can cut through the daily grind. And while classical music might seem like a stuffy museum of serious faces, composers have given us plenty of giggles over the centuries.

Mozart Joke

Mozart’s Divertimento for Two Horns and Strings in F Major, K. 522, is like the 18th-century equivalent of a musical prank call. It is a deliberate trainwreck of bad composing, written in 1787 to poke fun at every hack and mediocre musician. To be sure, Mozart throws in every compositional cliché he can think of.

© wfmt.com

We hear repetitive phrases and off-key surprises, with the strings playing along like they forgot how to read music. The horns honk at the worst possible moments and in silly keys, and the transitions are simply awkward. Still, it’s catchy and brilliant. It’s the kind of piece that makes you laugh out loud. Are you laughing with Mozart, or is he secretly laughing at you?

Satie Joke

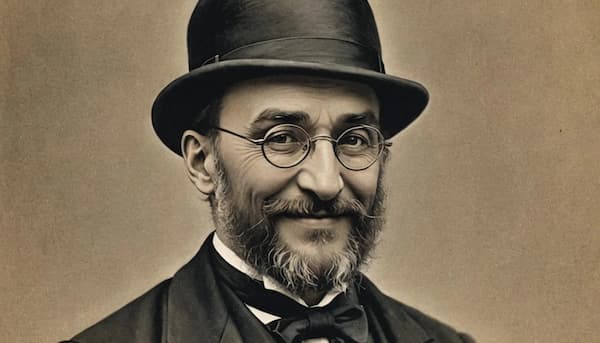

Erik Satie

The French musical maverick Erik Satie gave the world his “Three Pieces in the Shape of a Pear” in 1903. This piano duet isn’t just a composition, it’s a wacky response to stuffy critics who whined that his music lacked form. The title alone is enough to make you laugh, and in fact, it’s actually seven pieces and not three.

The music itself is a delightful mess of quirky melodies, wonky rhythms, and moments when the piano is daydreaming about being in a circus. Satie throws in some playful titles and instructions, like “play with a very profound gentleness,” and “Prolongation of the Same.” The pieces meander through dreamy waltzes like a conversation between friends that keeps changing topics. We can’t help but laugh at such sheer silliness.

Alkan Joke

The reclusive piano wizard Charles-Valentin Alkan unleashed his “Funeral March on the Death of a Parrot” in 1858. This piece is exactly what it sounds like. It’s a mock-serious dirge for a dearly departed parrot, complete with all the pomp and circumstance you might expect for a fallen feathered friend.

It’s pure musical satire with a solemn and plodding rhythm that sounds absurdly grandiose. Alkan piles on the melodrama with heavy chords and exaggerated tempos. Can you hear the quirky little flourishes and dynamic shifts? It’s like Alkan is snickering behind the music and daring you to keep a straight face. This is musical trolling at its finest, and somewhere, the parrot’s ghost is squawking with glee.

Haydn Joke

Franz Joseph Haydn was basically the original musical prankster, and his String Quartet Op. 33, No. 2 is nicknamed “The Joke” for very good reasons. This piece shows Haydn at his most impish as he lures listeners into a false sense of security with its chipper melodies and polite classical vibes.

In the finale, Haydn pulls out all the stops. Just when you think the music is wrapping up with a tidy little bow, Haydn throws in a cheeky pause, and when everybody gets ready to clap, he restarts the music with a cheeky encore. I bet he had some stuffy aristocrats looking like fools. Pure, mischievous and utterly funny genius!

As we celebrate “World Laughter Day,” let’s raise a glass to the musical jesters who turned stuffy concert halls into serious giggle celebrations. Let’s tip our hats to the genius composers who weave hilarity into their harmonies, proving that music can spark laughter around the world.

Thursday, May 8, 2025

YOUR LOVE - Ennio Morricone, from "Once Upon A Time In the West"

Friday, May 2, 2025

5 May 1891: Opening Night at Carnegie Hall

by Georg Predota

New York audiences and music lovers were treated to a momentous occasion in May 1891. Specifically, they witnessed the inaugural concert at Carnegie Hall, a concert venue in Midtown Manhattan in New York City, on 5 May 1891. Carnegie Hall would soon rise to become one of the most prestigious venues in the world of music.

Carnegie Hall in 1895

The vision of a dedicated Music Hall was the brainchild of Leopold Damrosch, conductor of the Oratorio Society of New York and the New York Symphony Society. His son Walter, who met the businessman Andrew Carnegie during his studies in Germany, carried Leopold’s vision forward. Eventually, he was able to convince Carnegie to donate 2 million dollars and the Oratorio Society and New York Symphony bought nine lots at the southeast corner of Seventh Avenue and 57th Street.

Andrew Carnegie

They approached architect William Burnet Tuthill, a talented amateur cellist and board member of the Oratorio Society to design the Music Hall. Tuthill had engaged in extensive studies of European concert halls, and he brought his experience with acoustics to bear on the Carnegie Hall project.

“Old Hundred” arr. Vaughan Williams

Designed in a modified Italian Renaissance style, the cornerstone for the Music Hall was laid by Carnegie’s wife Louise on 13 May 1890. Within the next 12 months, the original five-story brick and limestone building “containing a 3,000-seat main hall and several smaller rooms for rehearsals, lectures, concerts, and art exhibitions,” began to take shape. Andrew Carnegie said, “It is built to stand for ages, and during these ages, it is probable that this Hall will intertwine itself with the history of our country.” The Recital Hall opened in March 1891, and the Oratorio Hall in the basement opened on 1 April 1891. The Music Hall officially opened on 5 May 1891, starting a five-day Opening Week Festival.

William Burnet Tuthill

Contemporary reports write of “horse-drawn carriages lining up for a quarter-mile outside, while inside the Main Hall was jammed to capacity.” Conductor Walter Damrosch led the New York Symphony Orchestra and the Oratorio Society on Opening Night, and Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky had been engaged for a guest appearance. He was apparently paid $5,000 for his service, which in today’s money equates to roughly $150K.

A contemporary eyewitness reports, “People are swarming everywhere trying to get into this magnificent hall. The architecture is absolutely gorgeous with a façade made of terra cotta and iron-spotted brick. I manage to get inside where the main hall is jammed to capacity. I look around to see that the magnificent architecture extends to the inside as well. I looked up at the boxes to see the Rockefellers, Whitneys, Sloans, and Fricks families. I find my seat, smooth my dress, and sit down.”

Carnegie Hall Opening Festival poster

The program opened with the hymn “Old Hundred,” a tune from the second edition of the Genevan Psalter. It is considered one of the best-known melodies in the Western Christian musical tradition, and it was the first work transmitted by telephone during Graham Bell’s first demo at the American Academy of Arts and Sciences in 1876. Bishop Henry Codman Potter delivered a lengthy speech praising Carnegie’s philanthropy. Walter Damrosch entered the stage and the hall erupted in applause. The New York Symphony played “America,” and Beethoven’s Leonore Overture No. 3. A member of the audience reported, “The acoustics are even better than I could imagine.”

Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky: Marche solennelle

Then it was Tchaikovsky’s turn. In his diary, he writes, “In a crowded carriage I reached the Music Hall. Illuminate and packed with the public, it made an exceptionally striking and grandiose impression…The pastor gave a long and, it was said, exceptionally tedious speech, and after this, there was a very good performance of the Leonore Overture. Interval. I went downstairs. Excitement. My turn came. I was received very noisily. The march (Marche solennelle) went off beautifully. A great success! I listened to the rest of the concert from Hyde’s box. Berlioz’s “Te Deum” was rather tedious; it was only at the end that I really began to enjoy it.”

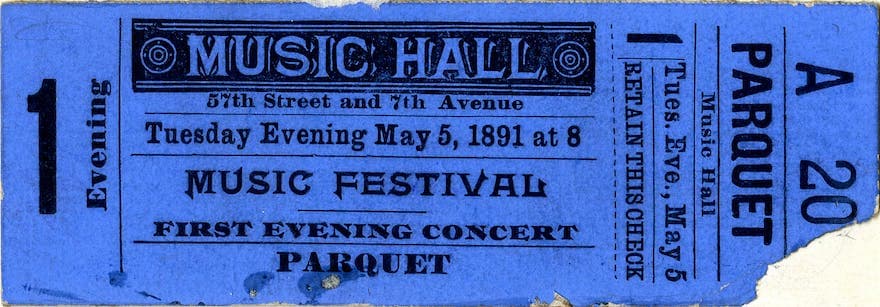

Ticket from the Opening Night at Carnegie Hall

Tchaikovsky was also less than enthusiastic about the review he read in the papers the next day. As he records in his diary, “Tchaikovsky is a tall, gray well built interesting man, well on the sixty?!!! He seems a trifle embarrassed and responds to the applause with a succession of brusque and jerky bows. But as soon as he grips the baton his self-confidence returns.”

Carnegie Hall at night

Tchaikovsky was rather annoyed and added, “It makes me angry that they not only write about music, but about me personally. I cannot bear it when they comment on my embarrassment, and marvel at my brusque and jerky bows.” Tchaikovsky did not have much time to ponder the review, as he was in the audience at the second concert, which featured Mendelssohn’s oratorio “Elijah.”