Throughout history, music has been both a reflection of and a response to societal and political climates. Under authoritarian regimes, art—particularly music—has often been a target for censorship. Whether deemed politically subversive, ideologically incorrect, or culturally inappropriate, certain works were banned, silenced, or suppressed in an attempt to control the narratives and voices that music can powerfully communicate. This article explores the lives and works of composers whose music faced censorship, showcasing the deep intersection between art and politics and the resilience of composers who faced suppression under totalitarian regimes.

Alban Berg (1885–1935)

Alban Berg, 1920s

Alban Berg was an Austrian composer known for emotionally intense music bridging late Romanticism and modernism. A key figure in the Second Viennese School, Berg studied under Arnold Schoenberg and created atonal music that expanded emotional and structural expression. Despite his non-Jewish status, his connection to Schoenberg and atonality made him a target of the Nazi regime’s campaign against “degenerate music.”

Berg’s opera Wozzeck, premiered in 1925, was groundbreaking for its atonality and acclaimed. However, with the Nazi rise in the early 1930s, his works were labeled “degenerate” and banned in Nazi-controlled areas. This suppression affected his later opera Lulu and the Lulu Suite, which also faced condemnation. The Lulu Suite premiered in Berlin in 1934 but met resistance, resulting in conductor Erich Kleiber’s resignation in protest. By 1935, all performances of Berg’s music were prohibited in Nazi Germany, and although his Violin Concerto premiered posthumously in 1936, it reflected the peak of censorship. While not openly denounced like some composers, Berg’s music remained silenced during a highly oppressive period of the 20th century.

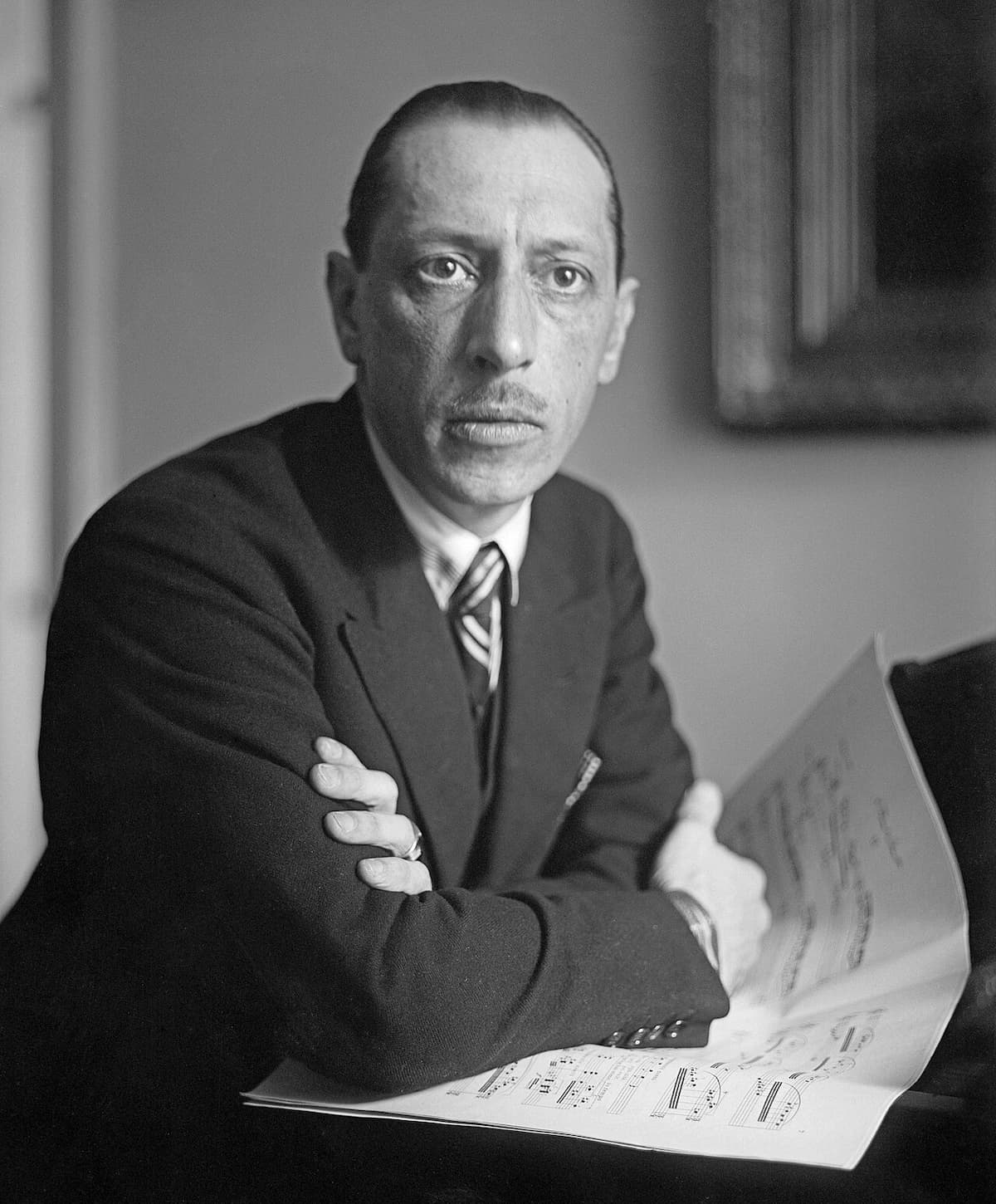

Igor Stravinsky (1882–1971)

Igor Stravinsky

Igor Stravinsky, one of the most influential composers of the 20th century, is best known for his revolutionary ballets The Firebird, Petrushka, and The Rite of Spring, which shattered conventional music traditions. However, Stravinsky’s avant-garde approach did not endear him to all regimes, particularly those with ideologically driven artistic policies. His music was banned and suppressed in the Soviet Union, particularly after the 1917 revolution, when he criticized the regime and emigrated. Stravinsky, a celebrated figure in Russia, soon found himself labeled an enemy of the state.

In Soviet Russia, much of Stravinsky’s music was denounced as bourgeois and formalist. His early works, including The Rite of Spring, were deemed decadent and inaccessible by the Soviet authorities, leading to their prohibition. It was not until the 1960s, after Stravinsky’s return to Russia under tight surveillance, that some of his music was cautiously reintroduced. However, for most of his life, Stravinsky’s works remained largely banned in his home country, silenced by a regime that feared the influence of Western, modernist thought.

Dmitri Shostakovich (1906–1975)

Dmitry Shostakovich, 1942 (Red Star newspaper, No. 86 (5150) from 12 April 1942)

Dmitri Shostakovich, one of the greatest composers of the Soviet Union, became a symbol of artistic survival under the oppressive policies of Joseph Stalin. Shostakovich’s music, which often oscillated between personal expression and forced compliance, faced constant scrutiny. His opera Lady Macbeth of Mtsensk District (1934), initially acclaimed, was suddenly criticised by the Soviet regime in 1936 after a scathing review in Pravda, labeled as “muddle instead of music.” This criticism led to the withdrawal of several of his works and years of self-censorship as he navigated the complex relationship between artistic freedom and state control.

Shostakovich’s Fourth Symphony was suppressed before its premiere, while other works such as the Eighth Symphony and From Jewish Folk Poetry were banned due to their perceived political implications and pessimism. Despite moments of official rehabilitation, Shostakovich’s compositions remained under the threat of censorship for most of his life, reflecting the constant tension between artistic expression and political pressure.

Ding Shande (1911–1995)

Ding Shande © sin80.com

Ding Shande, a prominent Chinese composer, faced significant challenges during China’s Cultural Revolution (1966–1976), a period marked by extreme censorship and the suppression of anything deemed “bourgeois.” Western classical music was viewed as a symbol of imperialism, and many of Ding’s works—rooted in Western tradition—were suppressed during this era. His Long March Symphony, a composition that celebrated the Red Army’s historic journey, was initially well-received but later faced suppression as China’s political climate turned against any perceived foreign influence.

While Ding’s music was not banned in the same way as Western composers, his ability to compose and perform freely was restricted under the Cultural Revolution’s stifling ideological control.

Grażyna Bacewicz (1909–1969)

Grażyna Bacewicz

Polish composer Grażyna Bacewicz is widely regarded as one of Poland’s most accomplished musicians. During the Nazi occupation, she endured the harsh conditions imposed on Polish artists but continued to create, often in secret. Bacewicz, along with other musicians, performed clandestine concerts to keep music alive during the war. After the occupation, she faced more formal repression during the Communist regime, which had a distaste for modernist styles. Her works, particularly her String Quartet No. 2, were composed and performed in defiance of the occupying forces.

Bacewicz’s music became a symbol of resilience in the face of oppression, demonstrating the power of music to both resist and survive under harsh conditions.

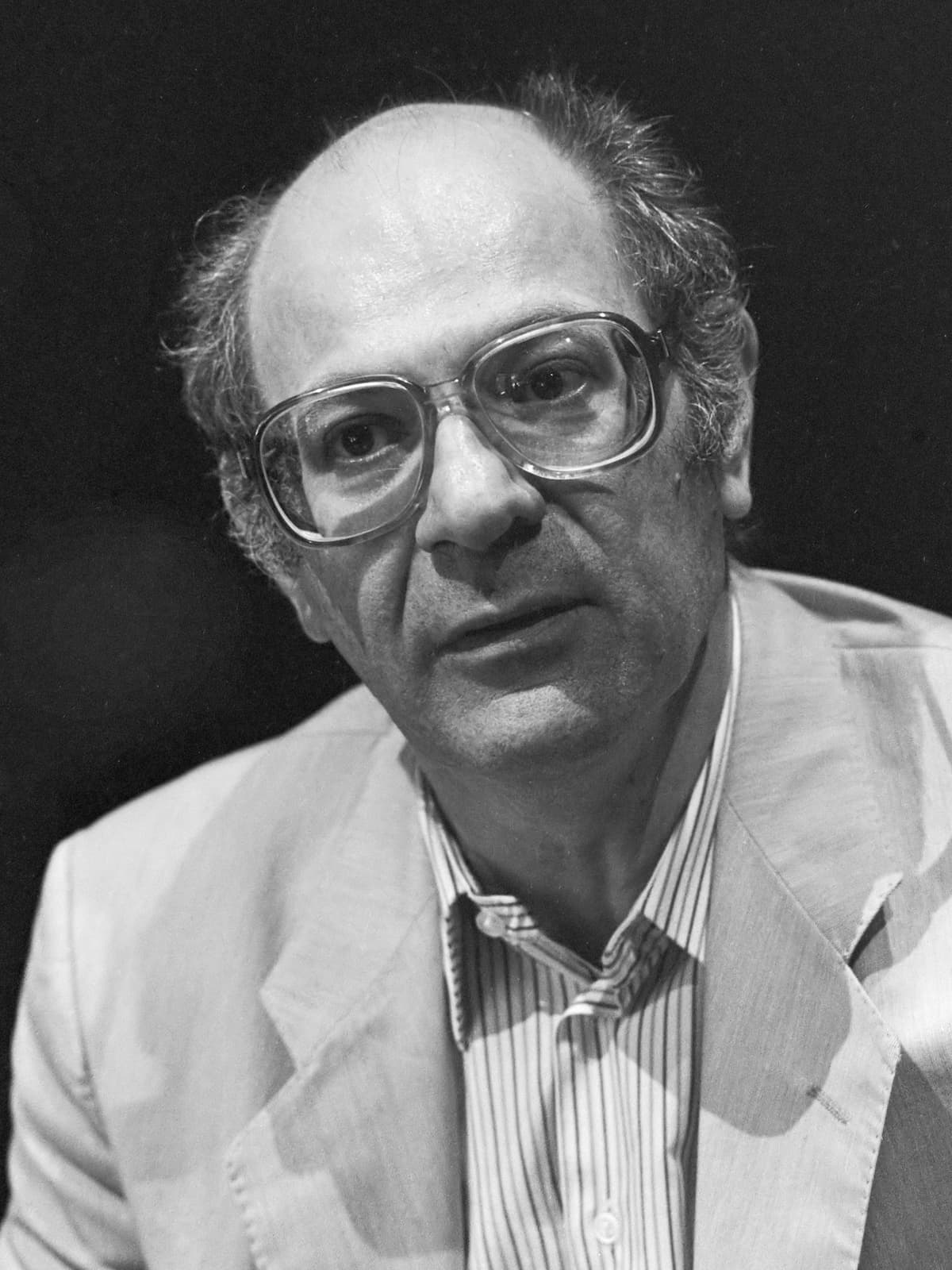

Witold Lutosławski (1913–1994)

Witold Lutosławski

Witold Lutosławski was another prominent Polish composer whose music faced suppression under the Communist regime in Poland. Lutosławski’s compositions, particularly his First Symphony, were labeled “formalistic” and banned by authorities for being too complex and nonconformist. His music, which often challenged the conventions of Soviet-approved style, was seen as a threat to the ideological conformity that the regime sought to maintain. Despite these challenges, Lutosławski’s music gained recognition on the international stage, and he became a leading figure in 20th-century music.

Lutosławski’s works, once banned at home, have since become staples of the classical repertoire, symbolising the triumph of artistic freedom over political oppression.

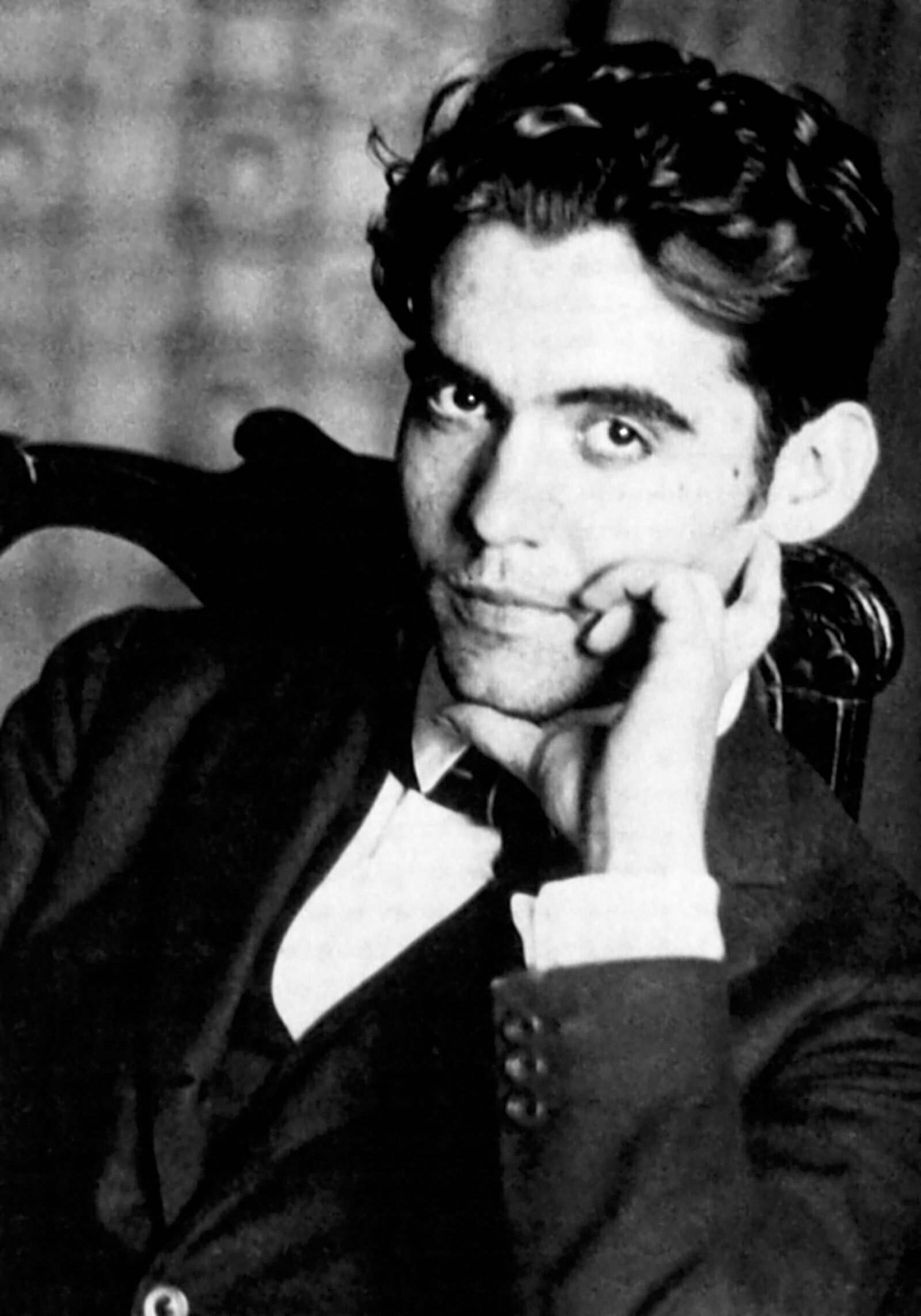

Federico García Lorca (1898–1936)

Federico García Lorca

Federico García Lorca, a celebrated Spanish poet and playwright, also made significant contributions to Spanish music, particularly through his collection and arrangement of traditional Spanish folk songs. His Colección de canciones populares españolas (1931), created in collaboration with the singer La Argentinita, highlighted the beauty of Spanish folk traditions. However, due to Lorca’s political beliefs and personal identity—he was openly gay and a Republican during Spain’s turbulent years—his works faced severe censorship under Franco’s dictatorship.

After his tragic assassination in 1936, many of Lorca’s works were banned, and his folk song collection was suppressed as part of the Franco regime’s effort to stifle cultural and political dissent. It wasn’t until after Franco’s death in 1975 that Lorca’s music was revived and began to regain its place in Spain’s cultural landscape.

Paul Hindemith (1895–1963)

Paul Hindemith, 1923

Paul Hindemith, a German composer and violist, found himself on the receiving end of Nazi censorship. His music, which combined modernist and neoclassical elements, was initially accepted but soon became targeted due to its perceived lack of alignment with Nazi ideals. Hindemith’s opera Mathis der Maler, which explored the role of the artist during political strife, sparked controversy, and by 1936, his works were banned in Germany. Faced with increasing persecution, Hindemith left Germany and eventually settled in the United States, where he continued his compositional career.

Despite his international success, Hindemith’s legacy in his home country was temporarily erased due to the oppressive political climate.

Mauricio Kagel (1931–2008)

Mauricio Kagel

Mauricio Kagel, an Argentine-born composer, became known for his experimental and theatrical approach to music. Kagel’s works often defied conventional musical boundaries, using irony and satire to critique societal norms and political regimes. While living in Germany, Kagel’s compositions like Ludwig van (1970) and Staatstheater (1971) were controversial for their audacity and critiques of cultural institutions. Staatstheater, in particular, faced significant resistance and even required police protection for its premiere. Although Kagel’s music was not officially banned, his works were suppressed in politically conservative environments, including during Argentina’s military dictatorship.

Kagel’s contributions to experimental music serve as a testament to the power of art to resist and critique authoritarian power structures.

Gilberto Mendes (1922–2016)

Gilberto Mendes © Wikipedia

Gilberto Mendes, a Brazilian composer known for his avant-garde approach and political activism, also faced censorship, especially during Brazil’s military dictatorship (1964–1985). While his music was not formally banned, works like Motet em Ré Menor and Santos Football Music were unofficially suppressed due to their political subtext. Mendes used his compositions to criticize societal and political issues, and this led to his music being withdrawn from festivals or omitted from broadcasts. Despite these challenges, Mendes remained a steadfast advocate for artistic freedom, helping to redefine Brazilian music in a time of political repression.

The experiences of these composers reflect the complex and often painful intersection of art, politics, and censorship. Music has long been a powerful force for both expression and resistance. Through their work, composers like Berg, Stravinsky, Shostakovich, and others not only endured suppression but also used their art as a form of defiance. The censorship of their music serves as a reminder of the enduring power of music to transcend oppressive regimes, offering hope, resistance, and a lasting legacy of resilience in the face of adversity.