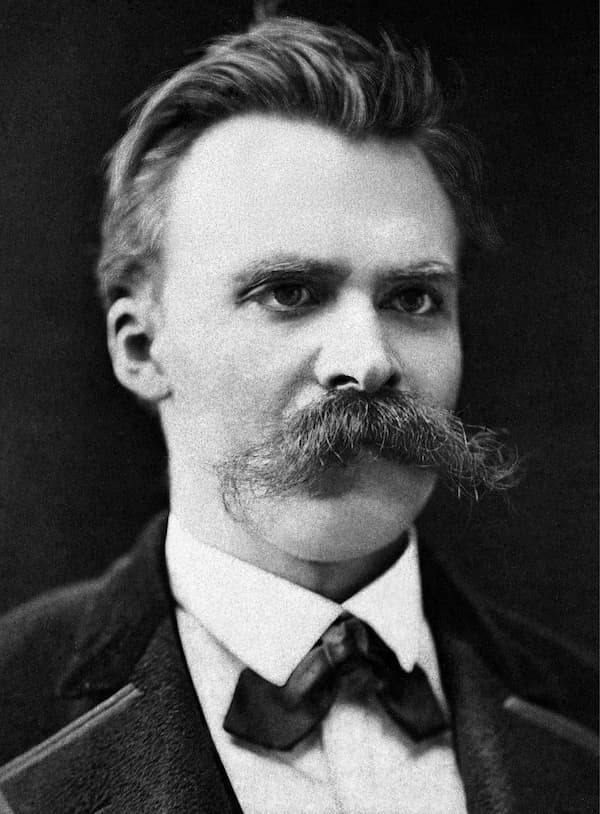

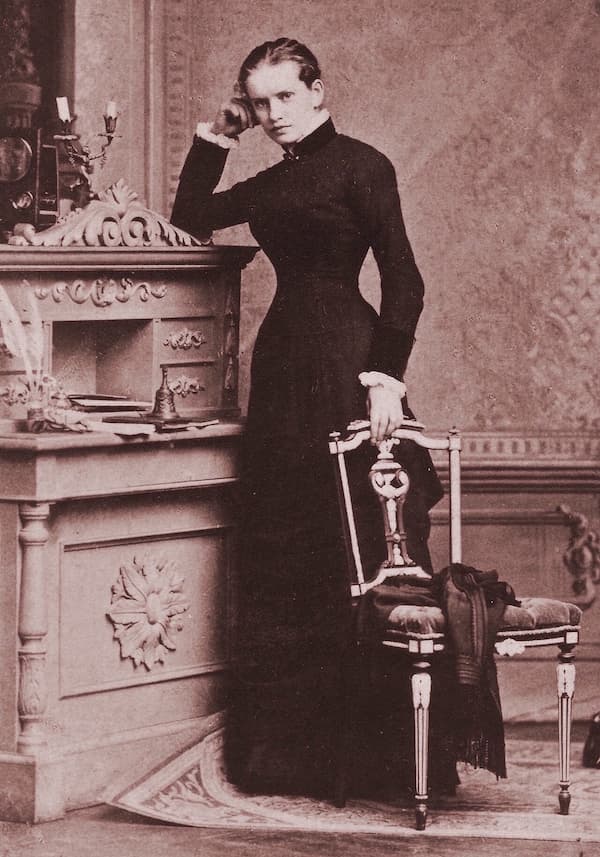

Friedrich Wilhelm Nietzsche at 21

Essentially, Nietzsche questioned the value and objectivity of truth, looking at God as a historical process and construct. Nietzsche wrote numerous texts on morality, contemporary culture, philosophy and science. Interestingly, he never really trusted the written word. He wrote, “all communication through words is shameless. The word diminishes and makes stupid; the word depersonalises, the word makes what is uncommon common.”

It might come as a surprise, but music was actually Nietzsche’s true love. Descended from a family of pastors where music and theology went hand in hand, young Friedrich was an accomplished pianist and organist by the time he reached the age of seven. At that age, he already played several Beethoven sonatas, transcriptions of Haydn Symphonies, and he was skilled in the way of improvisation. A couple of recent recordings have engaged with Nietzsche’s piano compositions, so we decided to take a closer look.

Reminiscences on my Life

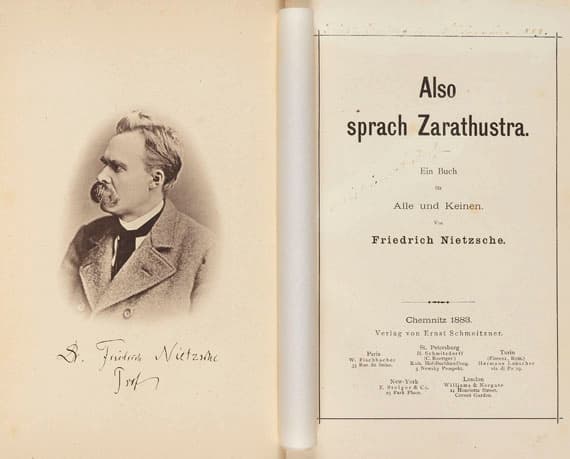

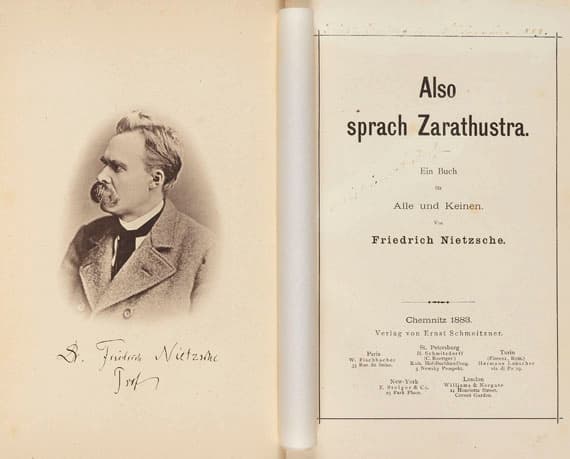

Friedrich Wilhelm Nietzsche’s Thus Spoke Zarathustra

Young Nietzsche initially improvised his own melodies, yet he soon moved on to sketch motets, symphonies, masses and oratorios, most of them unfinished. As he grew up, Nietzsche switched to smaller forms, particularly Lieder and piano pieces. As pianist Jeroen van Veen writes, “these pieces reflect the philosopher as a human being, vulnerable and desirous, but above all melancholic.”

At the age of 14, Nietzsche wrote his “Reminiscences on my Life.” He explained, “All qualities are united in music: it can lift us up, it can be capricious, it can cheer us up and delight us, nay, with its soft, melancholy tunes, it can even break the resistance of the toughest character.”

“Its main purpose, however, is to lead our thoughts upward so that it elevates us and even deeply moves us. All humans who despise it should be considered mindless, animal-like creatures. Let music, this most marvellous gift from God, remain forever my companion on the pathways of life.”

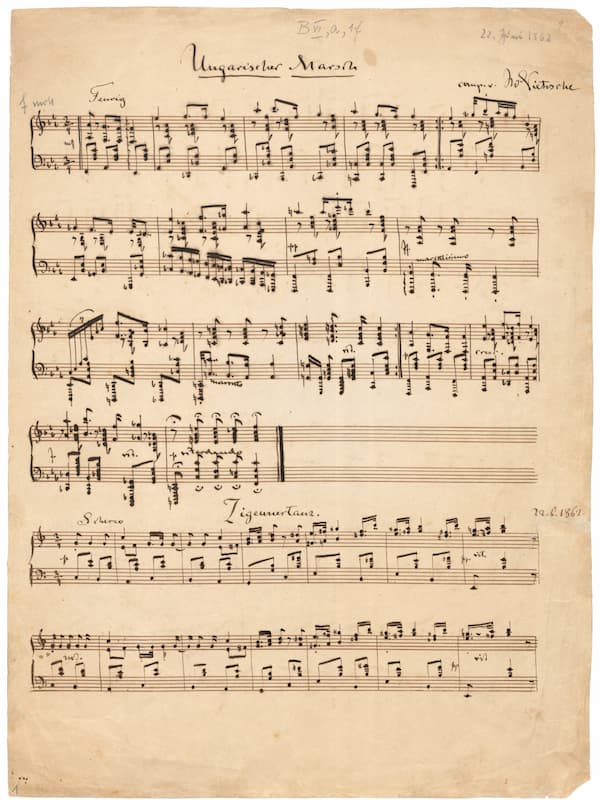

Barbarous Frenzy

In his “Reminiscences on my Life,” Nietzsche carefully listed his writings and his compositions, and at age fourteen, he had 46 compositions to his name. The earliest Lieder settings of Klaus Groth, the Hungarian poet Sándor Petöfi, Pushkin and Hoffmann von Fallersleben, were all composed “in a kind of barbarous frenzy, as the demon of music took hold of me.”

Nietzsche never took composition lessons, as he was essentially self-taught. He described himself as “a wretched youth who tortured his piano to the point of drawing from it cries of despairs, who with his own hands heave up in front of himself the mire of the most dismal greyish-brown harmonies.”

The Germania

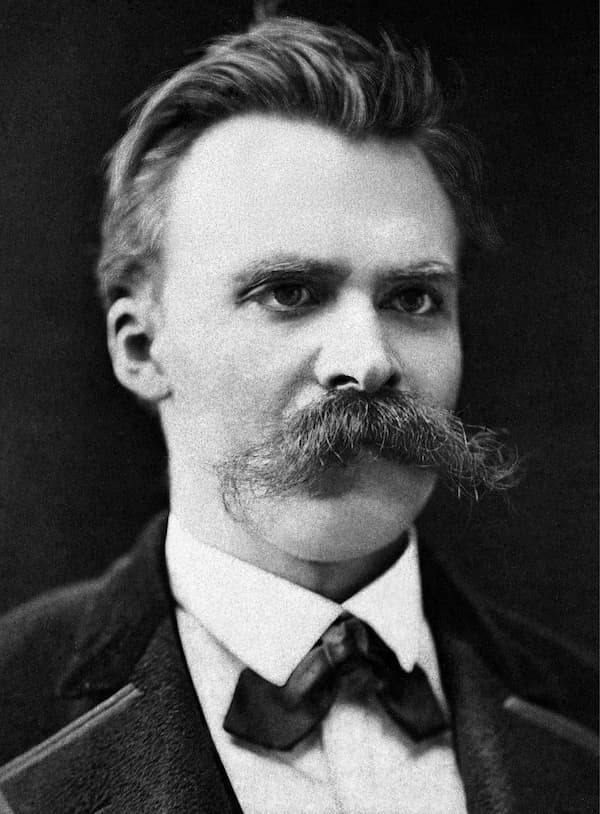

Friedrich Wilhelm Nietzsche

At the age of 16, Nietzsche started on a Christmas oratorio that was never finished. However, he would develop several themes for later use in subsequent compositions. “I look for words for a melody that I have and for a melody for words that I have, and these two things I have don’t go together, even though they come from the same soul. But such is my fate.”

Nietzsche’s early piano music is frequently dedicated to family and friends. Together with two young friends, he founded a small society called “The Germania,” which was dedicated to the “development of the spirit.” They would send each other compositions and poems, lectures and articles. And Nietzsche loved to improvise. A fellow student listened to these improvisations and wrote, “I should have no difficulty in believing that even Beethoven did not play extempore in a more moving manner.”

Assessment

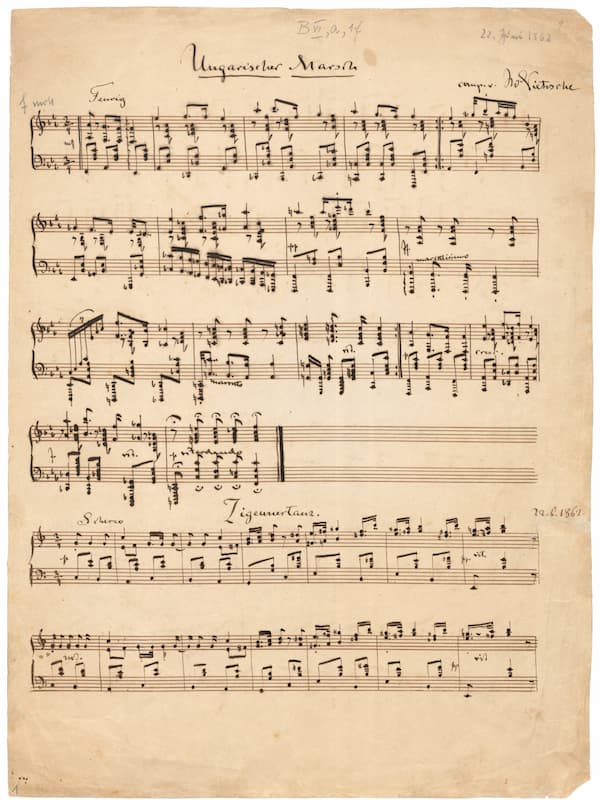

Friedrich Wilhelm Nietzsche’s Hungarian March

However, assessment from professional sources was less encouraging. Nietzsche sent Hans von Bülow, son-in-law of Richard Wagner, his “Manfred Meditation” for evaluation. Bülow was not impressed and wrote, “this music is the most extreme in fantastic extravagance and the most unsatisfying and most anti-musical composition I have seen in a long time. Is this a joke that deliberately mocks all rules of tonal harmony, of the higher syntax as well as of ordinary orthography?”

“In musical terms, this piece is the equivalent to a crime in the moral world, with which the musical muse, Euterpe, was raped. If you would allow me to give you some good advice, just in case you are actually serious with your aberration into the area of composition, stick with composing vocal music, since the word can lead the way on the wild sea of tones. I apologize, esteemed Herr Professor, of having thrown such an enlightened mind as yours, into such regrettable piano cramps.”

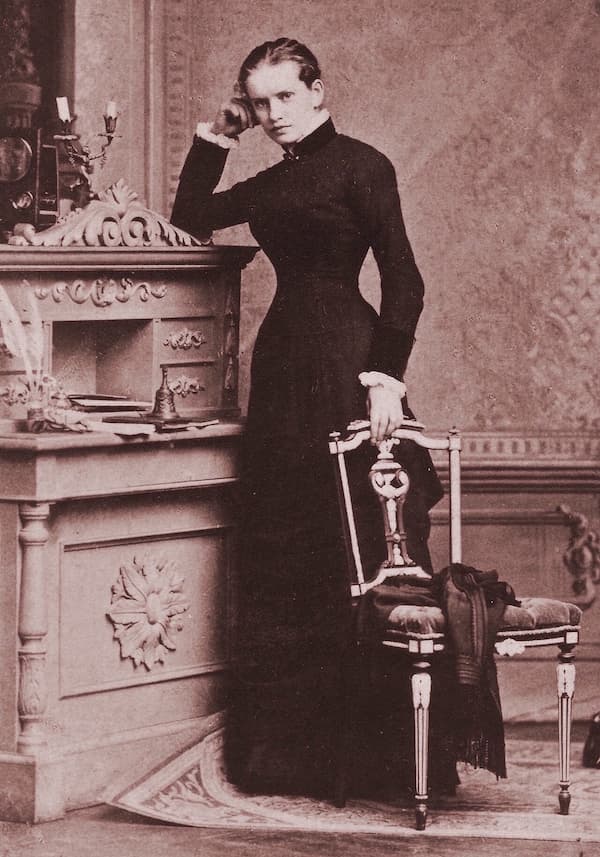

Lou Salomé

Lou Salomé

Nietzsche’s “Hymn to Life” is based on a text by Lou Salomé, a Russian-born psychoanalyst, well-travelled author, narrator, and essayist. At a literary salon in the city, Salomé met the author Paul Rée, who instantly proposed to her. Salomé declined and suggested setting up an academic commune, which was joined by Nietzsche in April 1882. He instantly fell in love with her as well, but she rejected him twice. Instead, Salomé, Rée, and Nietzsche travelled in search of setting up their commune in an abandoned monastery, but as no suitable location was found, the plan came to naught.

We do find an interesting assessment of Nietzsche by Salomé, which reads, “The higher he rose as a philosopher in his exaltation of life, the more deeply he suffered, as a human being, from his own teachings about life. This battle within his soul, the true source of the philosophy of his last years, is only imperfectly represented in his words and books, but it sounds perhaps most profoundly through his music to my poem Hymn to Life.”

Sabbatical

After completing the “Hymn of Life” and receiving Bülow’s devastating letter, Nietzsche wrote, “As for my music, I only know that it allows me to master a mood that unsatisfied, would perhaps produce even more damage. If music serves only as a diversion or a kind of vain ostentation, it is sinful and harmful. Yet this fault is very frequent; all of modern music is filled with it.”

After receiving this letter, Nietzsche did not touch his piano for a while, but in the end, “his awareness of being an amateur was overshadowed by his urge to become a better person, through music,” writes Vrouwkje Tuinman. As Nietzsche frequently proclaimed, “Emotions, morals, the world: the only way to (maybe) grasp the essence of being is surrendering to the highest of art forms,” he writes again and again. “Without music, life would be a mistake.”

The Affair Wagner

Richard Wagner

During his time as Professor of Philosophy at Basel University, Nietzsche became a close personal friend of Cosima and Richard Wagner, then living in Swiss exile. He was a regular house guest and even had his own room at Tribschen. We know that Nietzsche fell in love with Cosima Wagner, and he certainly composed some music for her.

Nietzsche dedicated his first book, “The Birth of Tragedy” to Wagner, proclaiming Wagner’s music the modern rebirth. The first part of the book was developed from long conversations between Cosima, Wagner and Nietzsche, roughly around the same time that Wagner began to develop the story of what eventually would become the “Ring Cycle.”

Postlude

Cosima Wagner

Nietzsche offered Richard and Cosima his “Reminiscence of a New Year’s Eve,” but they basically ignored it. In turn, Nietzsche started to object to Wagner’s “endless melody,” suggesting that listening to Wagner’s music made his whole body feel discomfort. He called it “a music without a future,” and that the effects of Wagner’s music are “for idiots and the masses.”

Nietzsche suffered a mental breakdown at the age of 44, from which he never recovered. For the last eleven years of his life, he was no longer able to speak or write, but he continued to play the piano. Listening, performing and composing music became an unconscious philosophical activity for Nietzsche, who had suggested earlier that “sound allowed me to say certain things that words were incapable of expressing.”

Editors of Nietzsche considered his compositions “amateurish and lacking in originality.” However, composing for Nietzsche meant experimentation and therapy, as he famously wrote, “we have art so not to die from the truth.” His piano music continues to be explored, and scholars write that “these piano miniatures present a fascinating window into the creative mind of a still-lofty figure in Western thought.” To me, his piano music, an elaboration of the conflicted world of Schumann, sounds hesitant and even unguarded, and the occasional ray of optimism is quickly cast aside by all-pervasive melancholy.