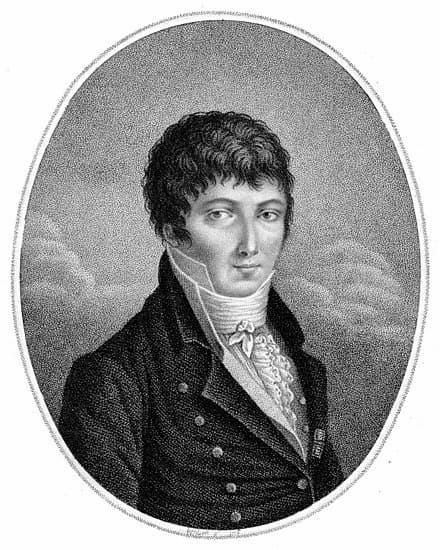

From his public relations-issued pictures alone, British-Indonesian pianist George Harliono struck one as having the best of both worlds—the Eurasian handsomeness that can only issue from the fine mix of two races.

But beyond good looks, he struck his first-time Manila audience as a young—he’s 23 years old—flaming talent to watch. The audience at the Ayala Museum wouldn’t let him go after he struck the last chords of Igor Stravingsky’s “Trois Mouvements de Petrouchka.” Filipino pianist Mariel Ilusorio, seated on the side front row, led the standing ovation. He obliged with Piazzolla’s “Libertango” as first encore.

The people didn’t cease applauding after that, and what followed was an extreme crossover to pop tunes like “Over the Rainbow” and the Elvis Presley ballad “Can’t Help Falling in Love.”

The purist in music reviewer and writer Pablo Tariman, who tried to shout “Chopin!” above the din, said if Harliono played another light ditty, he would place a candelabra on the Steinway & Sons grand piano (lent by the family of the late piano pedagogue Henrietta Tayengco-Limjoco) a la Liberace!

Tariman was good for a few guffaws, but we thought Harliono deserved better, considering he played a repertoire that was scarcely heard in the Philippines: Beethoven’s “The Tempest”; Mikhail Glinka’s “The Lark”; Mily Balakirev’s “Islamey”; Jean-Philippine Rameau’s “Les Tendres Plaintes”; Tchaikovsky’s “Dumka”; and the Stravinsky fireworks.

No wonder the hall attracted many piano majors and graduates, mostly from the University of Santo Tomas, or students of master piano accompanying artist Najib Ismail.

Wilder reception

According to witnesses, the reception for Harliono, who performed at the Luce Auditorium on the 123rd anniversary of Silliman University in Dumaguete City, was even wilder. While the Ayala Museum added some additional chairs for the Aug. 23 performance, the auditorium in the prime university in the south was packed with cheering students.

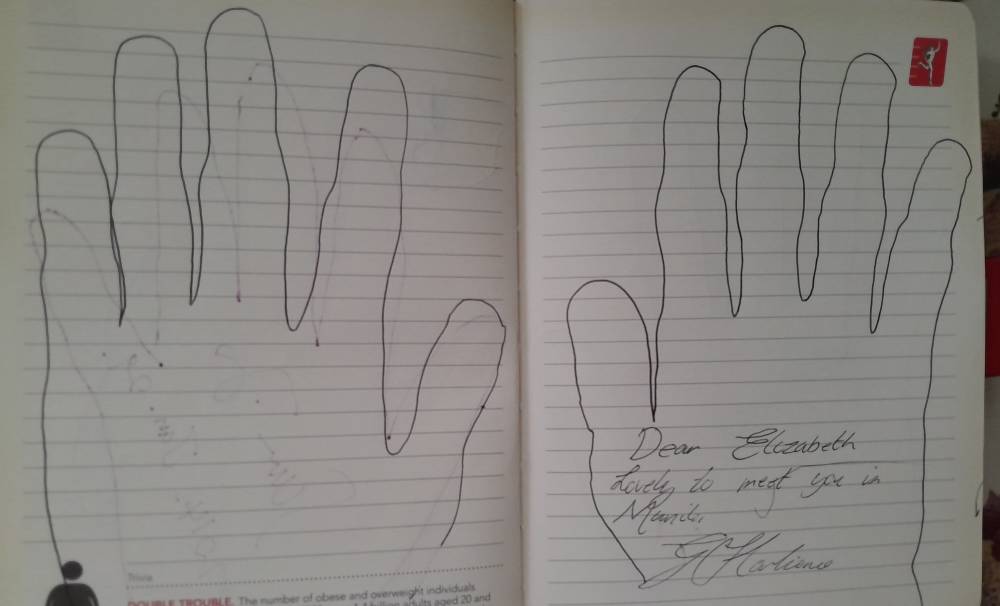

In an interview with the Inquirer Lifestyle at Café Romulo, where he was feted with a buffet dinner, Harliono described his Filipino audiences as “warm and kind,” so kind that they plied him with food and gifts like sterling silver cufflinks. Those who came, he added, were “young audiences, half of whom are studying the piano. It was nice seeing them look enthusiastic to meet me. I’m glad they enjoyed my program.”

At first, he thought that his program was “too heavy and serious,” so he also prepared lighter encores. He said the serious program was meant for those who study music, while the encores were “for those who don’t come ordinarily to classical music concerts.”

That evening at the café, he was seen talking at length with Ilusorio. Asked what their subject was, he replied, “It was about my teacher Pascal Nemirovski, with whom Mariel had a master class some 20-25 years ago.” The young pianist described his teacher as “very scary and strict but one of the best. In his 60s, he has mellowed. He’s now kind and sweet to me. His other students have won the Leeds and Tchaikovsky piano competition prizes.”

‘Halo-halo’ and adobo

He said that in the beginning, it felt strange to be of Indonesian and British parentage. “I grew up in a small town. I looked more Asian when I was small, then more European or Hispanic, even Mexican, in college.”

He continued, “I want to get more in touch with my mother’s Indonesian side. I was never taught to speak Bahasa. Now I understand a little. I can now spend four months in Indonesia to learn more.”

While he used to enjoy concertizing in Europe, he now wants to play more frequently in Southeast Asia, China and Russia.

To relax, he listens to Tchaikovsky symphonies and orchestral works by other composers. He said, “I don’t listen to piano. I’m more of an orchestra listener. Most pianists, when they’re in a train or a car, don’t listen to music. We would rather watch the view.”

Of the Filipino food he tried, he would like to come back for halo-halo and the Holiday Inn Makati’s pork adobo.