by

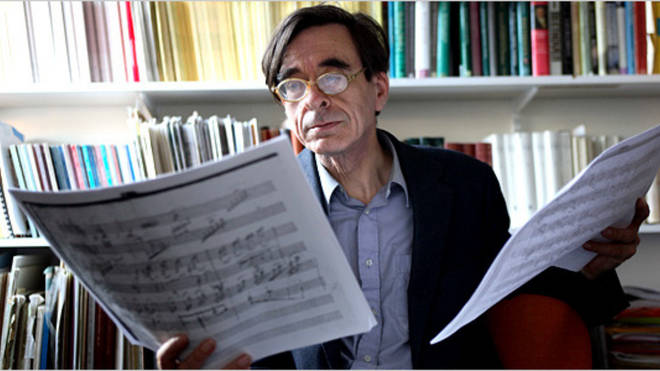

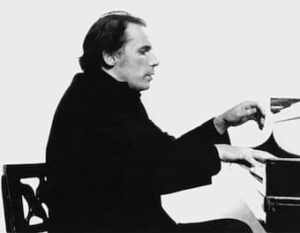

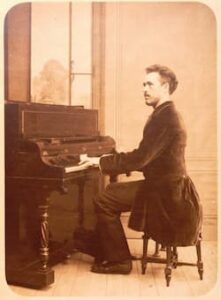

Glenn Gould

Glenn Gould is my favourite pianist. There, I said it. The reason I like him is because he is unconventional; unconventional in his approach to the stuffy world of classical music, unconventional in his interpretations, and unconventional in his mannerisms. Maybe I should have said idiosyncratic or eccentric. Eccentricity and non-conformity are no doubt part of the cultivated public image, but there is something very powerful in the way he tenderly strokes the keys like it is the memory of a long lost lover, or how he hums and groans incomprehensible along with the music. But there is one more thing I really liked about Glenn Gould, and that is the fact that he hated practicing. He would go days or even weeks without touching the piano, and he once claimed that the “best playing I do is when I haven’t touched the instrument for a month.”

Czerny: The School of Velocity

Piano practice just wasn’t very high on his list, and supposedly he practiced less than most during his concert years. After his retirement, he spent even less time at the piano. It is said, that from the mid-seventies, “he was practicing, when at all, as little as half an hour a day, usually about one hour, never more than two.” For us mere mortals, however, piano practice is essential, and countless composer have written dedicated exercises to keep our fingers nimble and wrists supple. We thought it might be fun to look and listen at music specifically composed for the purpose of piano practice, all starting with the probably most hated composer in the history of piano playing, Carl Czerny.

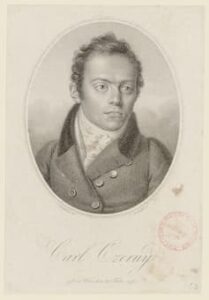

Carl Czerny

The name Carl Czerny (1791-1857) seems to automatically evokes great fear and loathing in aspiring pianists, but his technical exercises remain an essential part of nearly every pianist’s training. The idea that Czerny was a mere pedagogue churning out a seemingly endless stream of uninspired works actually originates with Robert Schumann. He writes, “It would be hard to discover a greater bankruptcy in imagination than Czerny has proved.” I think Schumann misses the point. The School of Velocity, The Art of Finger Dexterity, and countless others didactic pieces are solely and stubbornly concerned with acquiring and maintaining piano technique.

Czerny: The Art of Finger Dexterity

We all know how difficult it is to build up muscle dexterity and muscle memory, and how easy it is to fall off the cliff. The great violinist Jascha Heifetz once said, “If I don’t practice one day, I know it; two days, the critics know it; three days, the public knows it.” Czerny’s aim is clear, get your piano technique sorted first and then worry about making music. Czerny was pretty thorough in his aim, and his various “Schools” combine pedagogy with revelations about contemporary performing practices. Chopin greatly admired Czerny, as did Franz Liszt. In fact, the much-hated Carl Czerny is actually “considered the father of modern piano technique.”

Friedrich Burgmüller

It’s one thing to train the muscles of your hand, but quite another to keep your mind and ears interested in the process. As such, composers and pianists far and wide have tried to make the process of piano practice more interesting. Take for example Friedrich Burgmüller (1806-1874), a German composer and pianist. He settled in Paris and made his living as a much-esteemed piano teacher. His compositions proved successful among amateurs, as he wrote pieces of limited technical challenges, but coupled with the satisfaction of musical interest. Today, we primarily remember him for three collections of children’s etudes for the piano. These studies range from early intermediate to more advanced skills, and instead of simply numbering them from 1 to 12, Burgmüller provides descriptive titles. The charming salon pieces of his opus 105, for example, carry evocative names like “Chant du printemps,” “L’enchanteresse,” “L’heure du soir,” “Harpe du nord,” and others. These lovely little miniatures are an absolute joy to play, and they still “provide the basis for piano teaching and the development of technical proficiency.”

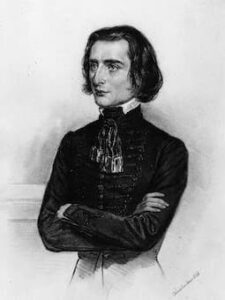

Franz Liszt

Franz Liszt (1811-1886) seems to have been born on a piano bench. In time, as we all know, he became the greatest piano virtuoso of his time, and possibly the greatest pianist of all time! His sensational technique and captivating concert personality turned him into the ultimate rock star of the 19th century. His incredible aptitude for playing the piano manifested itself at an early age, and in 1819, Liszt became a student of Carl Czerny. Czerny recalled, “He was a pale, sickly-looking child, who, while playing, swayed about on the stool as if drunk… His playing was…irregular, untidy, confused, and… he threw his fingers quite arbitrarily all over the keyboard. But that notwithstanding, I was astonished at the talent Nature had bestowed upon him.” It seems that even the great Franz Liszt was made to work through a number of Czerny exercises to stop throwing around his fingers arbitrarily. Liszt must have understood very early on that the key to success was found in technical proficiency. Why else would he have started work on the most significant of his first published compositions, the Etude en douze exercices at the age of thirteen. The collection consists of twelve different exercises, each an independent study dealing with a certain technical problem. These exercises did become the basis for Liszt’s “Grandes Etudes,” but at the time, they “appeared to be an excellent alternative for the more demanding studies of Czerny.”

Stephen Heller

Born in Hungary, Stephen Heller (1813-1888) was also looking to study with Carl Czerny in Vienna. However, Czerny was not only very famous, he was also very expensive. Heller couldn’t afford the tuition and learned his craft elsewhere. He did embark on an extensive concert tour through Hungary, Poland and Germany at the age of fifteen, and by the age of twenty-five, he settled in Paris. Heller established a distinctive concert presence, which eventually paved the way for the establishment of his well-respected piano studio. He was a prolific composer for the piano, and the first of his more than 160 published piano compositions date from 1829. Even the normally suspicious Robert Schumann predicted “a successful musical future for Heller.” He was first noticed in Paris as a composer of piano and concert studies, which were actually performed by Liszt and others throughout Europe. Scholars have suggested, “His reputation as a composer primarily of studies became so entrenched that he had difficulty in gaining recognition for his other music.” When it comes to piano practice, however, Heller’s studies have a great sense of rhythmic vitality and lyricism, and they are really fun to play.

Muzio Clementi

Muzio Clementi (1752-1832) published his three-volume Gradus ad Parnassum in 1817, 1819, and 1826. It represents, according to scholars “the culmination of his career, showcasing a veritable treasury of compositional and pianistic technique compiled from all periods of his work.” Clementi was in great demand as a piano teacher, and his students included members of London high society who could afford his substantial fees.

Clementi: Gradus ad Parnassum, Op.44

The Gradus is a collection of 100 pieces for keyboard that shows the full diversity of Clementi’s keyboard music. From finger drills to preludes, fugues, canons, character pieces, and sonata movements, more “than half the individual pieces are explicitly arranged into tonally unified suites of three to six movements… If the music in these volumes seems bent on exhausting all the possible varieties of keyboard figurations and textures, it also shows an underlying consistency.” Pianists of all levels have studied this treasury of compositional and pianistic technique continuously. This monumental work was designed to ascend to the highest level of musical and technical perfection. What a fabulous source of piano practice, as it trains your fingers and simultaneously hides that particular fact under cover of various musical styles and textures.

Johann Baptist Cramer

Let’s stay in London for a bit, and look at the piano practice of Johann Baptist Cramer (1771-1858). If you have ever taken formal piano lessons, there is a good chance that you will have played some of Cramer’s celebrated set of 84 studies for the piano. Published in two sets of 42 each in 1804 and 1810 as Studio per il pianoforte, it is still considered a cornerstone of pianistic technique today. With this collection, Cramer contributed directly to the “formulation of an idiomatic piano style through his playing and his compositions.” Cramer was a highly respected pianist, and Beethoven “considered him the finest pianist of the day.” He established a highly successful private piano studio in London, commanding top fees for his instruction. His “Studies for the Pianoforte” seem primarily concerned with matters of touch and the achievement of a singing tone. Yet at the same time, they are not mere exercises useful for an aspiring pianist, but also musically attractive to the listener. During his long professional life he witnessed monumental changes in musical styles and conventions, which he summed up by saying, “in the old days pianists played very well, and now they play awfully loud.”

Benjamin Godard

The French composer Benjamin Godard (1849-1895) might not be a household name today, but he was frequently compared to the young Mozart in his time. Godard entered the Paris Conservatoire at the age of ten as a violinist child prodigy, and he turned to composing shortly after. Godard, like a good many child prodigies was quickly forgotten, because he “somewhat abused his talent for commercial gain.” Nevertheless, Godard’s music is described as “full of charm and breathing a gentle spirit of melancholy.” An English critic wrote, “He can conjure up visions of the past, stir up memories of forgotten days … the best that was in him was perhaps expressed in works of small caliber, songs and pianoforte pieces.” Some of these delightful visions emerge in a set of three etudes published as Opus 149. The second volume, a set of six Etudes mélodiques opens with “Intimate Conversation,” in the manner of a Mendelssohn “Song without Words.” We also find a bright “May Song,” a “Nocturne Italien,” and a “Twilight Boating-Song.” Piano practice should be this much fun all the time, don’t you think?

Johann Nepomuk Hummel

Like many of his colleagues, Johann Nepomuk Hummel (1778-1837) was an enthusiastic writer of etudes. Without doubt, Hummel was one of Europe’s most famous pianists, and he was even hailed as the greatest of all the pianists on the continent. His playing was described as “full of clarity, neatness, evenness, pearly tone and delicacy, as well as an extraordinary quality of relaxation and the ability to create the illusion of speed without taking too rapid tempos.” Hummel was also one of the most important and expensive teachers in Germany, and both Schumann and Liszt were desperate to study with him, but never did. It almost goes without saying that Hummel was a prolific composer for his chosen instrument, and towards the end of his life he published a set of 24 studies in August 1833. A number of these etudes require great athletic ability, but “Hummel seems more interested in delicacy, color, expressiveness, emotional directness and, interestingly, veneration for the keyboard works of J.S. Bach.” The set is organized around the circle of fifths, and also includes some brilliant, witty, and song-like miniatures. Robert Schumann called the 24 studies “old-fashioned and not particularly relevant to modern pianists,” but he might have somewhat missed the point.

Frédéric Chopin

If you have ever taken serious piano lessons, you must surely remember countless hours of practicing scales and exercises to train and refine specific aspects of piano technique. To conclude this little survey on piano practice, I want to pay homage to Frédéric Chopin for turning mundane and boring finger exercises into a veritable art form. There is no arguing that his etudes are carefully constructed pedagogical pieces with a specific technical aim. However, they are simultaneously character pieces full of imagination, passion and poetry “seemingly communicating the essence of human experiences and emotions.” And what is more, they are composed for the concert hall. Chopin composed three sets of études between 1829 and 1839, and they “not only represent a developing style of playing that reflects the new aspects of the piano, but also provide an encapsulation of Chopin’s unique style.” Many etude composers before him had tried to achieve a balance between technical and artistic aims, but according to Schumann, in Chopin “imagination and technique share dominion side by side.” For me personally, these are probably the greatest etudes ever written. Many of the sampled composers have tried to find ways of transforming the sometimes frustrating, monotonous and always strenuous labor of practicing into a rewarding musical experience. What’s your favourite etude?

Composed for the cellist Heinrich Schiff in 1980, the work premiered at the Vienna Konzerthaus on 9 October 1981 with Schiff as the soloist and Gulda conducting. According to Gulda, Schiff only commissioned and performed this work because he wanted to make a recording of the

Composed for the cellist Heinrich Schiff in 1980, the work premiered at the Vienna Konzerthaus on 9 October 1981 with Schiff as the soloist and Gulda conducting. According to Gulda, Schiff only commissioned and performed this work because he wanted to make a recording of the