by

Publication History

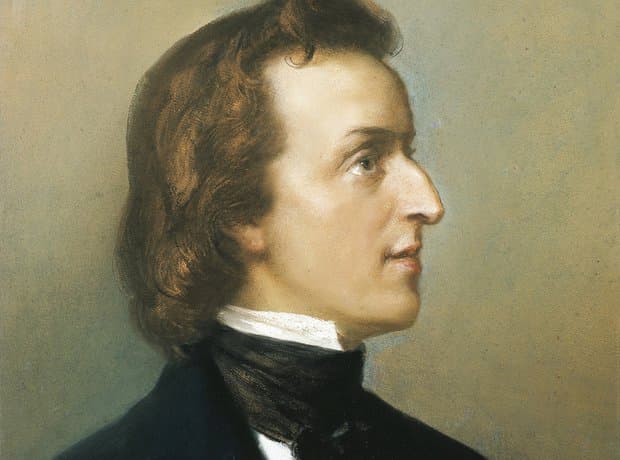

Frédéric Chopin

Chopin actually did not approve for his songs to be published at all. Juliusz Fontana, the composer’s friend and later the editor of the songs, mentioned that in Paris, at emigrant evenings, Chopin “in the moments of hearty frankness would recite them with intonation and accompaniment of the piano, with a book of poetry in front of him, postponing the moment of writing them down.”

Chopin did extemporize his songs at various times, from possibly as early as 1827 when he was 17, to 1847, two years before his death. All but one of the texts is based on original poems by Polish contemporaries, many of whom Chopin personally knew. As only two of them were published in his lifetime, Chopin’s mother and his sister sought to bring them to the public by looking for a suitable publisher. By 1857 the remaining 17 Polish songs had been collected and issued as Chopin’s Opus 74 by the publishing firm of Heinrich Schlesinger.

Chopin’s Study With Józef Elsner

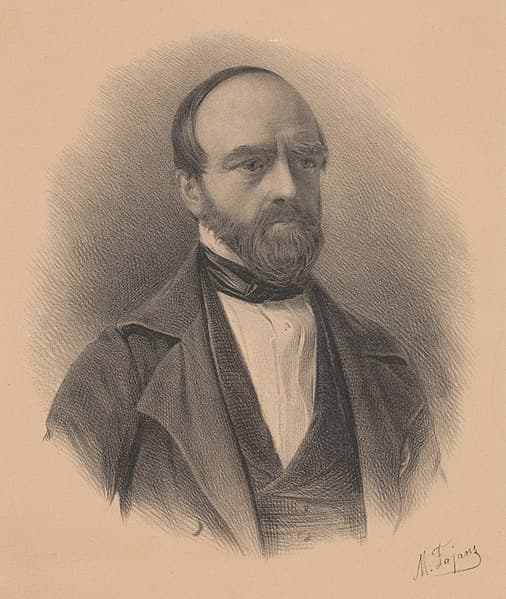

Józef Elsner

The Polish composer, music teacher, and music theoretician Józef Elsner is probably best known as the principal composition teacher of the young Frédéric Chopin. In his Treatise on Polish Poetry with Regard to Music of 1818, Elsner explored one of the most significant musical issues of his time. That being the creation of national music through the setting of contemporary, and often radical, Polish texts.

As he writes, “Every intelligent, creative person who understands the relationship between music and poetry, and who is connected to one of the other is deeply moved by it, must be aware of the shared perfection of the two arts. The influence of music on poetry, and poetry on music is so important, that one art form cannot be precisely and fully explained without reference to the other.”

The earliest Chopin art song in his Op. 74 collection was published only ten years after the publication of Elsner’s treatise. In fact, Chopin had been interested in art song composition from the time of his earliest studies with Elsner, and in his early group of songs, Chopin adheres strictly to “Elsner’s rules on the accentuation of penultimate syllables in closing phrases and section.”

If I were the sun in the sky

I wouldn’t shine just on you.

Neither on lakes

nor forests

but on everything;

Oh the times under your window and only for you

If I could only change into the sun.

If I were a bird from that forest

I wouldn’t sing in any foreign country

Neither on lakes

nor forests

but on everything;

Oh the times under your window and only for you

If I could only change into a bird.

(trans. Christopher Lapkowski)

Songs Composed During His Teenage Years in Warsaw

Frédéric Chopin, 1873

During his teenage years in Warsaw, Chopin seemed to have spontaneously composed a number of songs in a local coffee house. He regularly attended with his friends, and “Chopin would simply sit down at the piano and play.” The poet Stefan Witwicki (1801-1847) was part of the Chopin circle, and like the composer, he was interested in the ideals of Polish nationalism. Chopin set eight poems by Witwicki, beginning around 1829 with “Życzenie” (A Maiden’s Wish) and “Gdzie lubi” (Where She Loves).

These songs seemed to have quickly gained popularity and were circulated in copies with added accompaniment, and occasionally with changed lyrics. Chopin stayed in touch with Witwicki after he left the country, and in July 1831 the poet sent a letter to Vienna.

“Dear Mr. Fryderyk, let me remind myself to your memory. I would like to thank you for the songs. Both I and everyone who knows them like them very much and you would admit to yourself that they are very beautiful if you heard them performed by your sister. Your friend Witwicki… If you wanted to write music to another song…”

Chopin’s early songs feature, for the most part, regular four-measure phrasing subdivided into smaller two-measure units. He rarely employs successive melodic accents within the closing phase, “and his songs can perhaps be best interpreted as a transformation of original folk melody and vernacular text. Such melodies and texts are given new interpretations within the art song framework, particularly in terms of dramatic intent and ornamentation of accented syllables.” And while there are tangible allusions to folksong in Chopin settings, there is no documented evidence to suggest that the composer quoted directly from folk sources. My darling, when in a joyous moment

You begin to chatter and wail and coo,

Such lovely cooing, chattering and wailing

Not wanting to miss a single word,

I dare not interrupt, I dare not respond,

I only wish to listen!

But when the vividness of speech lights your eyes

And rosies the berries more intensely

Pearly teeth shine among corals,

Ah! then I will look boldly in your eyes

I hurry my lips and to do not demand to listen,

Only to kiss!

(trans. Jennifer Gliere)

Poetry by Adam Mickiewicz

Adam Mickiewicz

The Polish-Lithuanian poet Adam Mickiewicz (1798–1855) is regarded as a national poet in Poland, Lithuania and Belarus. A principle figure in Polish Romanticism, he is one of the so-called “Three Bards,” whose work was thought to give perfect expression to Polish nationalism. Chopin and Mickiewicz were close friends, particularly during the years when Chopin lived in Paris. Perhaps their most significant point of convergence was the intensity of their national feelings and the homesickness they both experienced.

Mickiewicz fondly remembered Chopin as “the sweetest figure” he had ever known. According to Robert Schumann, Mickiewicz supposedly inspired Chopin’s piano ballades, but we know with certainty that Chopin set two Mickiewicz poems. These settings are separated by about ten years, with the liltingly beautiful love song “My darling” written in 1837, and the declamatory “Out of my sight” dating from 1827.

Out of my sight! Leave me I beg you!

Out of my heart! I cannot go against you.

Out of my thoughts! No, that ultimate surrender

Our memories could ever render.

As evening shadows lengthen

And stretch their sad imploring arms,

My face will shine brighter in your mind

The further you are from me.

In every season in places close to our hearts,

Where we have shared laughter, tears and glances,

Always and everywhere shall I be with you,

For everywhere I have left a part of my soul.

Poetry by Bohdan Zaleski

Bohdan Zaleski

The Polish-Ukrainian poet Bohdan Zaleski (1802-1886) was part of the Mickiewicz circle, and an active member of a number of nationalist organizations, including the Slavonic Society and the Polish Democratic Society. Zaleski was associated with Romanticism and sentimentalism, and his love and reflective lyrics were inspired by folk poetry. Zaleski was a personal friend of Chopin, and his wife was the composer’s piano student between 1843 and 1844. In all, Chopin set four of Zaleski’s poems, and he seems to have been particularly interested in Zaleski’s historical dumkas.

Originating in Ukraine, the dumka was performed by itinerant Cossack bards and centered on historical events, often dealing with military actions. Although the narratives mainly revolve around war, they primarily impart a moral message in which one should conduct oneself properly in relationships with the family, the community, and the church. Chopin’s melody is reminiscent of a bard’s song, and the accompaniment mimics the strokes of the lyre. This is clearly a lyrical lament of a wanderer far from his homeland, a sentiment that Chopin could readily identify with.

My eyes mist over with tears from deep within me,

All around me darkness is gathering;

A dumka wells up and dies on my lips

In silence, ah, in the silence of unhappiness.

What bliss it would be to love and to sing!

Then I would dream in this alien

wilderness as I did at home;

I long to love — and there is no one.

I long to sing — and there is no one to sing to.

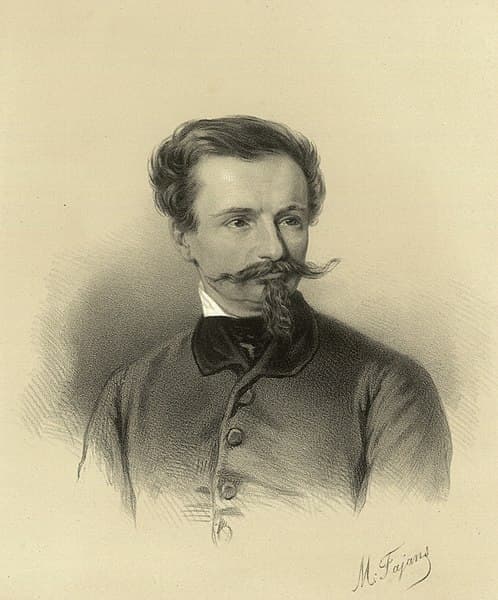

Poetry by Wincenty Pol

Wincenty Pol

The Polish poet and geographer Wincenty Pol (1807-1872) fought in the Polish army during the November 1830 Uprising. This armed rebellion in the heartland of partitioned Poland was fought against the Russian Empire. A substantial segment of people from Lithuania, Belarus, and Ukraine joined the uprising, and although the insurgents achieved local successes, a numerically superior Imperial Russian crushed the uprising. Pol published a collection of highly popular poems of the revolt titled “Songs of Janusz.” Apparently, Chopin composed music to ten or twelve of these, but only “Leaves are falling” has survived.

The leaves are falling from a tree

Which grew to maturity in freedom;

A little field bird sings

From on top of a gravemound.

O Poland,

You have fared badly!

It was all just a dream

And your children are dead.

Your hamlets have been burnt down,

Your towns destroyed,

And in the fields round about

A woman is lamenting.

Everyone left their homes,

Carrying their scythes with them;

Now there is no one left to work,

And the crops are wasting in the fields.

When the young men gathered

Near Warsaw,

It seemed as though the whole of Poland

Would cover herself with glory.

They had the upper hand all winter,

They fought the summer through;

But in the autumn

There were not even enough

adolescents left to continue.

Now the battles are over,

But all was in vain,

For none of our brethren are coming back

To their fields.

Some lie pressed beneath the sod,

Others have been led away captive,

Others are scattered throughout the world

With no home or farmland.

There is no help from heaven

Or from human hands;

The soil is lying waste

And Nature displays her charms for nothing.

The leaves are falling from the tree,

Again they are falling.

Oh, land of Poland!

If those countrymen

Who are dying for you

Had set to work

And carried away their homeland’s soil

A handful at a time,

They would already have built Poland

With their hands.

But distinguishing ourselves by a show of strength

Is nowadays beyond our imagining,

For traitors have proliferated

And the common people are too good-natured.

Chopin’s setting seems very much like a recorded improvisation. Rhapsodic in character, the song mourns the fate of a nation and of a generation rather than individual events. An expressive yet internalized interpretation takes away all of the threatening pathos, replaced with a subdued lament in an elevated mood.

Importance and Legacy

According to scholars, “Chopin’s songs brought to the European Romantic song repertoire a character and a tone it had lacked before. They brought the simplicity of a first-hand folkloric inspiration, an almost naive, youthful tenderness, a boisterous aplomb, a nostalgic reflection, and finally a deep feeling for one’s country.” For a number of critics, these songs are regarded as artistically unimpressive, and of minor significance in the entire creative work of the composer. To be sure, Chopin himself attached so little meaning to the songs that he never had a single song published. However, he surely wanted his vocal miniatures to fleetingly stir the emotions, to draw a smile or a tear. As such, “read with an understanding of tone and style, sung and played in a natural yet intimate way, they can charm and transform, move and disturb.”