From Felix Mendelssohn and his Romantic era landscapes to John Cage and his chance-driven ink washes, these five composers created drawings, sketches, and paintings that help illuminate their artistic inner worlds.

Today, we’re looking at the lesser-known art by five great composers.

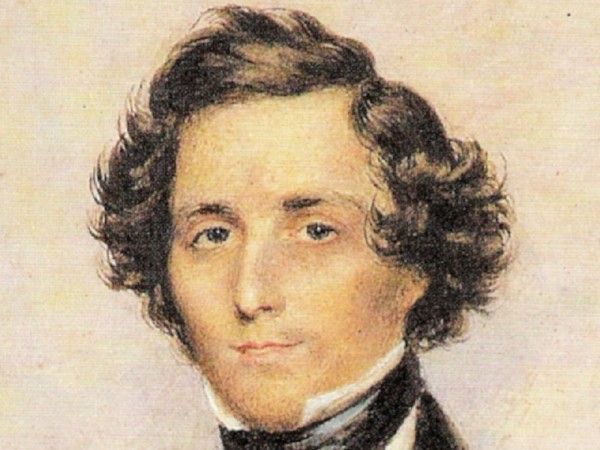

Felix Mendelssohn (1809–1847)

Felix Mendelssohn

Mendelssohn was not just a celebrated composer; he was also a prolific visual artist.

He began taking drawing and painting lessons at an early age. Over the course of his lifetime, he produced hundreds of pieces of art in pen-and-ink, watercolour, and oils.

It’s no surprise that this child of the early Romantic era favoured subjects like dramatic natural landscapes and historic architecture.

Mendelssohn’s landscape painting

During one family tour of Switzerland in 1822, the 15-year-old Mendelssohn drew over forty ink-and-pencil landscape sketches of the Alps.

Later trips to Scotland (in 1829) and Italy (in 1831) likewise inspired numerous scenic drawings and watercolours of breathtaking locales.

He would also create memorable musical portraits of those countries, most famously with his Hebrides Overture and his Fourth Symphony, nicknamed the “Italian.”

Mendelssohn wrote in 1838 that while vacationing in Switzerland, “I composed not even a bit of music, but rather drew entire days, until my fingers and eyes ached.”

The beloved hobby allowed him to remain creative even when he was struggling with finding musical inspiration.

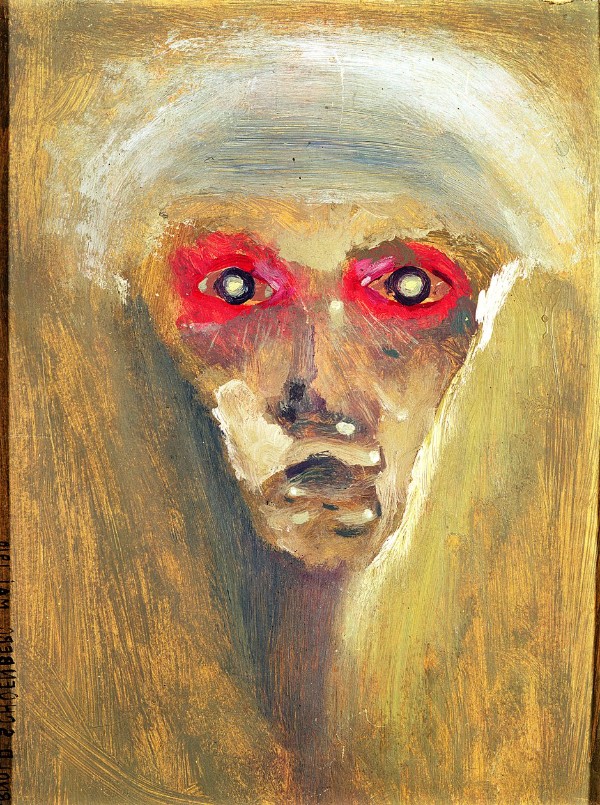

Arnold Schoenberg (1874–1951)

Composer Arnold Schoenberg is remembered best today as a composer and pioneer of atonality, but he was also a gifted Expressionist painter.

He began painting around 1907 and started focusing on the hobby in earnest months later during a particularly tumultuous period in his life.

Arnold Schoenberg

That year, his wife, Mathilde, left him for several months to have an affair with painter Richard Gerstl. After she returned to Schoenberg that November, Gerstl died by suicide.

While dealing with the emotional fallout, Schoenberg created a series of intense portraits characterised by stark colours, exaggerated features, and haunted gazes.

These paintings – which Schoenberg often titled “Gaze” or “Looking” – were meant to express something profound about his interior emotional state at the time of their creation.

He ended up aligning with the loose Vienna-based group of artists known as Der Blaue Reiter (The Blue Rider), named after Wassily Kandinsky’s 1903 painting of the same name.

In fact, Schoenberg showed paintings at the Heller Gallery in Vienna (1910) and in the Der Blaue Reiter exhibition in Munich (1911) at Kandinsky’s invitation.

Schoenberg painted around 60–70 paintings, mostly between 1908 and 1912. After 1912, his output dipped, and he returned to focusing on music.

Arnold Schoenberg’s self portrait, “The Red Gaze”

He later mused about the connections between the two arts in an interview:

I planned to tell you what painting meant to me. In fact, it was to me the same as making music. It was to me a way of expressing myself, of presenting emotions, ideas, and other feelings.

And this is perhaps the way to understand these paintings, or not to understand them. They would probably have suffered the same fate as I have suffered; they would have been attacked. The same would happen to them that happened to my music.

I was never very capable of expressing my feelings or emotions in words. I don’t know whether this is why I did it in music, and also why I did it in painting.

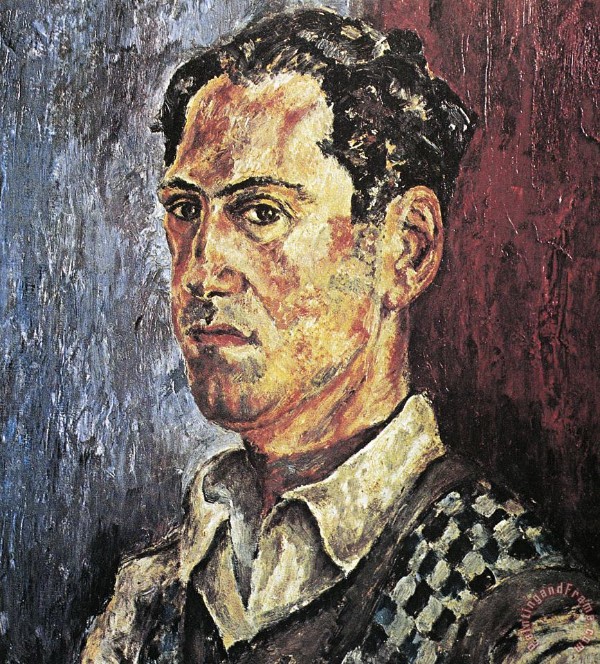

George Gershwin (1898–1937)

George Gershwin is famed as a composer of jazz-influenced classics, but he was also an avid painter: he created over 100 works during his lifetime.

He took up painting in 1927, encouraged by his younger brother Ira and their cousin, the artist Henry Botkin.

He worked primarily in oil painting and charcoal or pencil sketches, focusing on portraits and figure studies of the people in his world. He was especially fond of impromptu, casual portraiture.

George Gershwin, self-portrait, 1936

Among Gershwin’s best-known paintings is his portrait of his Hollywood tennis partner, fellow painter-composer Arnold Schoenberg (c. 1934–36). Today, that painting hangs in the U.S. Library of Congress.

George Gershwin painting Arnold Schoenberg

One friend, Merle Armitage, noted that Gershwin “was in love with colour and his palette in paint closely resembled the colour of his music. Juxtaposition of greens, blues, sanguines, chromes, and greys fascinated him.” Appropriate favourites for the composer of Rhapsody in Blue!

It should also be noted that Gershwin was an art collector as well as artist, owning works by Picasso, Chagall, Modigliani, Kandinsky, and others.

He even kept Mark Chagall’s painting, The Rabbi, over his piano, where he would see it every day he went to work.

It’s tantalising to think about how the aesthetics of these artists might have affected his own music.

As he once told a friend, “Painting and music spring from the same elements, one emerging as sight, the other as sound.”

Paul Hindemith (1895–1963)

Paul Hindemith, 1923

In addition to his compositions and viola-playing, German composer Paul Hindemith was known for his whimsical drawings.

Although he never formally trained as a visual artist, he drew prolifically from childhood until the end of his life.

He would regularly seize any scrap of paper at hand – menus, napkins, concert programs – and fill them with impromptu sketches and cartoons.

Hindemith’s doodles

His subjects were numerous and tended toward the bizarre: he’d portray whimsical, fantastic subjects in a cartoonish style, such as tubas with legs, cats who played musical instruments, or even dancing elephants.

Hindemith always treated his drawing as a casual, fun outlet. He never catalogued his visual art in any systematic way, or treated them as anything but throwaway doodles.

The only meticulously dated collection of Hindemith’s visual art is his series of Christmas cards, which he drew and sent out to friends, family, students, and colleagues every year. He kept up the tradition for decades, until his final Christmas in 1963.

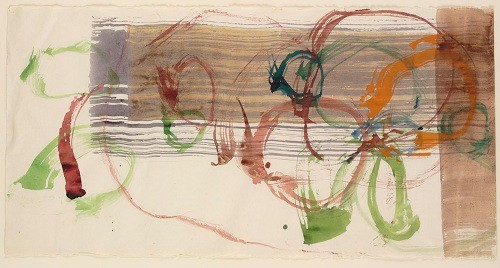

John Cage (1912–1992)

John Cage, avant-garde composer of 4’33” fame, created a significant body of visual art during the last twenty years of his life.

During the 1970s and 1980s, Cage turned to printmaking, drawing, and watercolour as extensions of his experimental philosophy. By the time of his death, he had produced a large and distinctive oeuvre of works on paper.

Cage’s visual art is notable for applying the same principles of chance and indeterminacy that he used in music. While making his watercolours and prints, Cage would let random operations guide the creation of the works.

John Cage’s painting

As a result, Cage’s art has a uniquely serene yet unpredictable quality – splashes of colour or delicate pencil lines appear according to coin flips and computer-generated randomness, not by his own subjective aesthetic judgment.

Cage’s largest sustained visual art project was done in collaboration with the Mountain Lake Workshop in Virginia. Between 1983 and 1990, he spent several week-long residencies there, creating a total of 125 unique watercolours. All of them were later published in the compendium The Sight of Silence: John Cage’s Complete Watercolors.

Conclusion

The visual artworks these composers left behind are compelling in their own right, but they’re also fascinating for what they say about their creative spirit and vision.

Whether it was Mendelssohn sketching alpine peaks in Switzerland, Schoenberg confronting his inner turmoil on canvas, or Cage embracing indeterminacy with brush and ink, each of these composers used visual media to explore ideas that sound alone didn’t allow them to.

Appreciating their artwork gives us an invaluable lens for hearing – and better understanding – their remarkable music.

.jpg)