by Georg Predota , Interlude

Caricature of Franz von Suppé

In his professional diary under 2 May 1841, Franz von Suppé writes, “First encounter with Therese Merville, my 1st wife.” We do know that Suppé age 22 and Merville age 25 married on 13 October 1841 in Preßburg, currently Bratislava. And we also know that their first daughter Anna was born on 2 February 1842. However, Suppé had already dedicated a song to Therese as far back as June 1838. The “Wiener Theater-Zeitung” reports “Suppé dedicated his setting of Schiller’s poem ‘For Emma’ to Therese Merville, which was published by Mr. Pietro Mechetti, in Vienna.” All very unremarkable, I hear so say, but why would Suppé actually lie about the time he first met his first wife? Well, it seems that Therese Merville had a bit of a reputation. That ill reputation was primarily based on a forty-page manuscript authored in the spring of 1833 by the Viennese municipal chancellor Engelbert Fürst. The ominous and rather verbose title reads, “Something about dealing with Miss Therese Merville, foster daughter of Mr. and Ms. Puchrucker.” And Fürst adds, “Intended as instruction and warning for men.”

Portrait of Franz von Suppé by Gabriel Decker, 1847

It appears that Mr. Fürst, a man of 35 years-of-age and an amateur singer had fallen deeply in love with Therese Merville, a girl of 17. He “considered her an earthly angel,” but her foster parents did not immediately want to commit to the honorable but poor Fürst, and Therese was allowed to inspect other “applicants for marriage” under the supervision of her foster parents. Therese, so it is reported, “flirted with any and all family guests on the occasion of house concerts and evening entertainments. Engelbert Fürst, a sensitive man who had decided after a long time to propose to Therese, finally withdrew, deeply offended by Therese’s coquetry.”

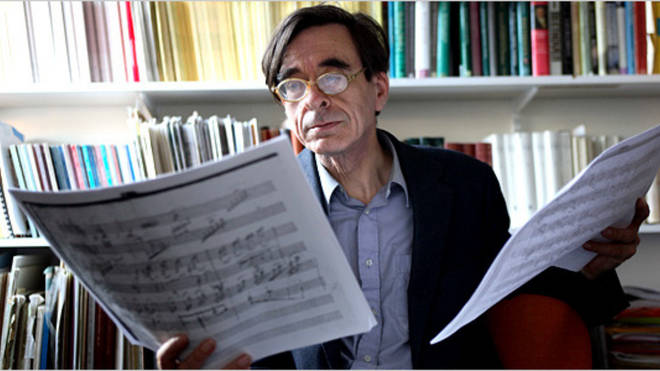

Sophie Strasser

As such, it is not known when, and under what circumstances Franz met Therese, but he clearly wanted this part of his biography kept secret. We know next to nothing about their married life, but by the autumn of 1852 both signed a divorce agreement. It detailed the conditions of separation and settled custody and maintenance payments for their children Anna (1842), Peter (1844) and Therese (1850). Therese von Suppé died on 23 May 1865, and Franz married the singer Sophie Strasser on 18 July 1866.

Suppé’s Pique Dame

As we have seen, Franz von Suppé wasn’t always up-front when it came to his private and personal life. And that trend continues in biographies dealing with his second wife. The biographer Otto Keller writes in 1905, “The summer of 1866 also brought a happy turn in the private life of the master. His first wife, from whom he had recently separated, had died on May 23, 1865. A year earlier he had met a lovely girl, Sofie Strasser. She was the daughter of ordinary citizens from Regensburg and was sent to Vienna to train for the stage. She was directed to the music director Suppé, who, since she was without special resources, placed and taught her in the choir of the Karltheater. But he soon saw that the voice was nice, but not enough for larger solo parts.” A closer look confirms, however, that Franz and Sofie had been a couple since at least June 1860, when Sofie worked in the choir of the Theater an der Wien. She was not only Suppé’s muse, but also most likely “the librettist of the opera Pique Dame.”

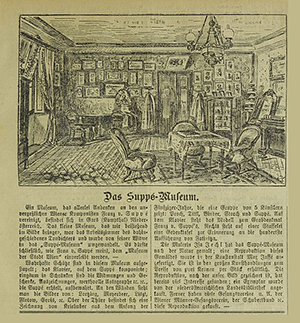

The Suppé Museum on newspaper

Franz and Sophie unofficially had been traveling as husband and wife since 1862. Although the civil courts had granted Franz’s legal divorce from Therese, in the eyes of the Catholic Church he was married “until death do us part.” In order to keep up the social decorum, however, Franz and Sofie von Suppé officially moved their acquaintance date to 1864, with the wedding taking place in 1866. Once again, we have little information about the marriage, but it has been suggested that Sofie was a major inspiration and staunch supporter for her husband’s works.

Suppé’s grave at the Zentralfriedhof

After Suppé died on 21 May 1895, his widow became his estate administrator and actively engaged in furthering the legacy of her late husband. She commissioned the young sculptor Richard Tautenhayn to design an artistic Suppé tomb for the honorary grave in the Vienna Central Cemetery. Between 1896 and 1908, she built and managed the Suppé Museum in Gars am Kamp, which she donated to the “City Collections of the City of Vienna” on 13 January 1902. In 1921 she gave the “Gesellschaft der Musikfreunde” the handwritten scores of 47 dramatic and numerous other orchestral and vocal works from Suppés’ estate. Sofie von Suppé died on 15 March 1926 in Vienna, and was buried in her husband’s honorary grave in Vienna’s central cemetery.