by Maureen Buja , Interlude

It's all about the classical music composers and their works from the last 400 years and much more about music. Hier erfahren Sie alles über die klassischen Komponisten und ihre Meisterwerke der letzten vierhundert Jahre und vieles mehr über Klassische Musik.

Total Pageviews

Wednesday, December 29, 2021

Tuesday, December 28, 2021

Muses and Musings - Bettina Brentano: Everybody’s Muse!

by Georg Predota , Interlude

Bettina Brentano

© Wikipedia

She aroused the curiosity of Napoleon Bonaparte and went for intimate walks with Karl Marx. She entertained a significant passion for Goethe, who deflected her craving into an extended correspondence and companionship, and she was Beethoven’s muse. Robert Schumann and Johannes Brahms dedicated songs to her, and the Grimm brothers devoted an edition of their fairy tales to her. Who was this incredible woman? Her name was Elisabeth Brentano, better known as Bettina. She was the sister of the famous poet Clemens Brentano, and the wife to another, Achim von Arnim, whom she bore 11 children. She never wrote poetry but her writings outraged and fascinated people, and she also composed music. Her first two songs appeared under the pseudonym “Beans Beor” (blessing, I am blessed). Approaching composition from a literary viewpoint, a number of her songs were published during her lifetime. Young virtuosos and composers like Franz Liszt, Joseph Joachim, Peter Cornelius and Johann Kinkel admired her as a friend of Goethe and Beethoven, and her influence on young musicians was of lasting importance. She was “a supreme muse, a one-woman literary movement, at once among the singular and most representative figures of the Romantic century.”

Johann Wolfgang von Goethe

© travel-target.com

Bettina was born in Frankfurt in 1785, and her mother had been Goethe’s first love. When she died, Bettina was sent to the convent, and eventually her mad brother Clemens—at some point he had painted his entire room, floor to ceiling, including the carpet, curtains, furniture, and his own face blue—became her mentor. Clemens and his friend Achim von Arnim, with substantial help from Bettina, collected folk poems, which they eventually published as the seminal work of German Romanticism, Des Knaben Wunderhorn. Bettina had always been a rebel, and her first love was a girl five years her senior whom she met in the convent. When she was 21, she was introduced to Goethe, and when he asked what interested her, she replied “Nothing interests me but you.” Apparently, “she leapt into his lap, threw her arms around his neck and went to sleep.” She clearly wanted to be his muse, maybe more. She wrote in a letter, “I have been jealous and sometimes I have felt myself to be the subject of your poems – and why shouldn’t I dream myself into happiness? What higher reality is there than dream?” Goethe, over 30 years her senior, did not know how to handle her, so he turned her letters into the materials for his books and poem, “but he kept her at arm’s length.”

© sueyounghistories.com

By 1810, Bettina had made herself known to another great artist of her age, Ludwig van Beethoven. According to her own recollections, “one day as Beethoven was working at the piano, I placed my hands on his shoulders. He turned in anger to find an attractive young woman who spoke melodiously in his ear: My name is Brentano.” Seemingly, Beethoven was enchanted by her forthright manner, and they developed a close friendship but were never lovers. She certainly was determined to bring Goethe and Beethoven together, which eventually happened in a single rather uneasy meeting. In her letters she kept quoting Beethoven and Goethe, but all the words were her own invention! Admirers suggest that Bettina created her own literary genre, the “epistolary novel.”

Bettina’s influence was felt throughout central Europe, and that included support for Johanna Kinkel, the female composer, writer, pianist and music teacher who published about 70 songs for voice and piano. Escaping from an abusive husband, Johann lived with Bettina von Arnim for several months, and helped her with compositions and translation projects. Her first collection of six songs, published under the name “J. Mathieux” is dedicated to her mentor, and the critic Ludwig Rellstab suggested, “She would soon become respected and well known.” Bettina tirelessly campaigned against anti-Semitism, wrote some seriously dangerous political books demanding liberalization of Prussian rule, and was even branded a communist. Her last book, Conversations with Demons almost ruined her financially, and looking at a bust of Goethe she died in her bed at 74. Scholars and critics agree that Bettina von Arnim was unique in a century rich with extravagant characters. “She was everyone’s muse, she craved love from every quarter, but she was never other than her own person. Her greatest creation was herself!”

Thursday, December 23, 2021

The Composer’s Block

by Doug Thomas, Interlude

Is the writer’s block (or composer’s block) avoidable? © Goalcast

Being stuck in front of an empty page is quite a common phenomenon for artists, regardless of the medium or format of the art. The writer’s block is the result of the creator not being able to produce new works, and unfortunately it can last for years. It is not only measured by the time elapsed without creating, but also by the productivity over time. A disease that all artists avoid like a plague, yet as much as one can try to steer away from being left with no inspiration, it is at times unavoidable. Some composers have made it a strength, an opportunity to reset, while some have suffered from it forever.

Is the writer’s block — or in this case, the composer’s block — avoidable? If so, how does one avoid the blank page as it is also known?

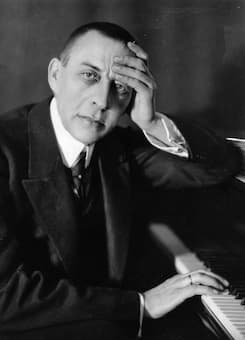

Sergei Rachmaninoff © euroarts.com

One of the most famous composers who has suffered from the blank page is of course well-knowingly Rachmaninoff, whose three yearlong depression resulted in a writer’s block, leaving the Russian composer unproductive for a long time. He is not the only composer though, Schubert faced difficulty in composing too when he became ill and depressed towards the end of his short life, and even Beethoven faced a few years of creative block, composing less than ten works for almost seven years!

There are a few ways around the writer’s block. Mozart, and many of his peers — despite having a very fertile brain — always composed following pre-set structures – including the harmonic structure — and all that was left to do was fill in the blanks with melodic material. Composing by numbers as one could call it!

Of course, the more one composes, the more the juices flow. When composing as a duty — in the case of Bach for instance — it is a lot easier to be more tolerant as well as detached from emotional and intellectual opinions, creative ideas are more easily accepted. The work has to eventually be completed! Creativity is like a muscle, it needs daily exercise.

Gardens Of The Villa Deste At Tivoli By Jean Baptiste Camille Corot

© Crescendo Magazine

One can use pre-existing material to plant the seed for inspiration, as does Nyman in his own interpretation of Mozart’s Don Giovanni in his In Re Don Giovanni. But the source does not necessarily require an existent musicality; other artistic works — in literature, painting — or even life experiences, such as travels, can provide a great source of inspiration. Think of Liszt’s Années de Pèlerinage, where the landscapes and cityscapes of Italy and Switzerland provide the canvas to the Hungarian composer’s masterpiece.

Eventually, another fantastic way to release the inspiration is of course to think outside of the box; compose for unusual instruments, unexpected settings, or in the case of Cage compose without composing; “4’33”, despite not containing a single note of music, it is one of the most inspired piece of work ever composed.

Some composers seem to have never been affected by the writer’s block and some others are well-known for having benefited from a lack of ideas to express, like Pärt — whose pause and return to music allowed him to come back with his true voice and expression and signature Tintinnabuli style. Outside of the music world, Frank Zappa or Bob Dylan are great examples of musicians whose regular and constant output allowed them not to ever feel the symptoms of the blank page.

One never quite runs out of ideas, rather one forgets how to find and reach them. Creativity is a stew which develops flavours over time and needs constant stirring and heat in order to express itself. The responsibility of the composer is as much to maintain his creativity boiling as to create.

The most adventurous composers rarely suffer from the writer’s block. It is rather for the ones that take shortcuts in their creativity, relying too much on their past achievements and waiting for external triggers to enable it to emerge.

Saturday, December 18, 2021

Camille Saint-Saëns - His Music and His Life

Camille Saint-Saëns in 1900

Camille Saint-Saëns (1835-1921) was one of the leaders of the French musical renaissance during the later part of the 19th century. He was a scholar of music history and tolerant of a wide range of musical issues and directions. He tellingly wrote: “I am an eclectic spirit. It may be a great defect, but I cannot change it; one cannot make over one’s personality.” His views on expression and passion in art conflicted with a prevailing Romantic aesthetic that was engulfed by Wagnerian influences.

Camille Saint-Saëns, 1846

In his memoirs he wrote, “Music is something besides a source of sensuous pleasure and keen emotion, and this resource, precious as it is, is only a chance corner in the wide realm of musical art. He who does not get absolute pleasure from a simple series of well-constructed chords, beautiful only in their arrangement, is not really fond of music.” Saint-Saëns possessed a mastery of compositional technique, and his ease, ingenuity, naturalness and productivity was compared to “a tree producing leaves.” Yet, during a period of extreme musical experimentations, Saint-Saëns remained stubbornly traditional, and by the time of his death on 16 December 1921, his compositional style was considered deliberately old fashioned. Scathing critical opinion suggested “Saint-Saëns has written more rubbish than any one I can think of. It is the worst, most rubbishy kind of rubbish.”

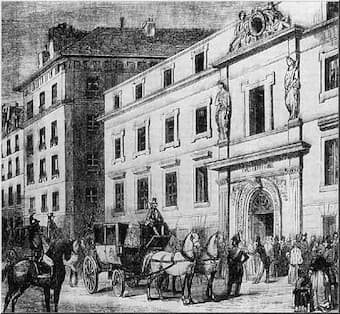

Saint Merri Church in Paris

Saint-Saëns was born in the Rue du Jardinet in the 6th arrondissement of Paris on 9 October 1835. Two months after the christening, his father died of consumption and young Camille was taken to the country. “It is not generally realized,” a music critic wrote, “that Saint-Saëns was the most remarkable child prodigy in history, and that includes Mozart.” He produced his first composition at age 3, and publically performed a Beethoven violin sonata at age 4. Saint-Saëns made his official public debut at the Salle Pleyel at the age of ten, performing piano concertos by Mozart and Beethoven. An anecdote tells that he offered to play as an encore any of Beethoven’s 32 piano sonatas from memory. Hector Berlioz admiringly wrote, “This young man knows everything, and he is an absolutely shattering master pianist,” with Franz Liszt declared him “the world’s greatest organist.” In addition to his musical prowess, Saint-Saëns excelled in his academic studies. He distinguished himself in the study of French literature, Latin, Greek, and Divinity. He acquired a taste for mathematics and the natural sciences, including archaeology, astronomy and philosophy. At the age of thirteen, Saint-Saëns was admitted to the Paris Conservatoire where he specialized in organ studies and took formal courses in composition.

The old Conservatoire de Paris, early 19th century

Saint-Saëns competed for the Prix de Rome in 1852, but the award went to Léonce Cohen instead. Upon graduation from the Conservatoire, Saint-Saëns accepted the organist post at Saint-Merri, and by 1858 he was appointed organist of La Madeleine, the official church of the Empire. Saint-Saëns became a teacher at the École de Musique Classique et Religieuse and he counted Fauré, Messager and Gigout among his most prominent students. Although he supported and promoted the music of Liszt, Schumann, and Wagner, Saint-Saëns wrote, “I admire deeply the works of Richard Wagner in spite of their bizarre character. They are superior and powerful, and that is sufficient for me. But I am not, I have never been, and I shall never be of the Wagnerian religion.” Going against the grain of French musical life in the mid-19th century, his main love was instrumental music. Extraordinarily active in the field of chamber music, not only as a composer but also as a performer, he might rightfully be considered one of the pioneers of French chamber music. Saint-Saëns left his teaching position in 1865 and pursued a career as a performer and composer.

Saint-Saëns at the piano for his planned farewell concert in 1913,

conducted by Pierre Monteux

Saint-Saëns was an excellent craftsman with a fine sense of musical style, and he placed his talents into the services of the Société Nationale de Musique. He wrote important articles in support of performing music by living French composers, and embarked on a number of operatic projects. His opera Le timbre d’argent had its première at the Théâtre Lyrique in 1877, and he scored a solid success with Samson et Dalila, a work that kept a foothold on the international stage. Saint-Saëns was elected to the Académie des Beaux-Arts in 1881, and he was made an officier of the Légion d’Honneur in 1884. Always a keen traveler, Saint-Saëns made 179 trips to 27 countries between 1870 and the end of his life. Avoiding Parisian winter, Saint-Saëns spent substantial portions of the year in Algiers and various places in Egypt. He resigned from the Société Nationale in 1886, and although his popularity in France began to wane, he was still regarded as the greatest living French composer in America and England.

Interior of Saint-Saëns’ tomb in Montparnasse

Saint-Saëns performed his last concert on 6 August 1921, and concluded his conducting career shortly thereafter. He died of a heart attack on 16 December 1921 in Algiers, and his body was taken back to Paris for a state funeral at the Madeleine. During a period immersed in modernism of all kinds, Saint-Saëns remained stubbornly traditional, and his steadfast dedication to musical moderation, clarity, balance and precision deservedly earned him the nickname “French Beethoven.” Contemporary critics, on the other hand, polemically called him “the greatest composer without talent.” From the perspective of music history, however, we now understand that Saint-Saëns compositional approach, deeply inspired by French classicism, was an important forerunner of the neoclassicism practices of Ravel and others.

E=Mozart2: Albert Einstein and Music

by Georg Predota , Interlude

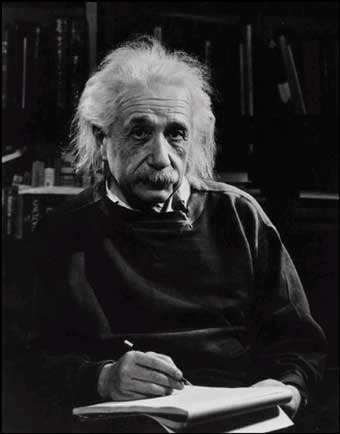

Albert Einstein in 1947 © biography4u.com

The German theoretical physicist Werner Heisenberg, who was awarded the Nobel Prize for Physics in 1925 for his work in quantum mechanics, suggested “The space in which a person developed as an intellectual/spiritual being has more dimensions than the space which he occupied physically.” In a personal sense, Heisenberg might reasonably have referenced his own personal development. In a cultural sense, however, we are hard pressed to ignore the connection of Heisenberg’s statement to the multidimensional phenomenon associated with his colleague Albert Einstein. His general theory of relativity revolutionized the field of physics, his work on the photoelectric effect won him the Nobel Prize in 1921, and his mass-energy equivalence formula “E=mc2” is almost universally recognized. Yet he also exists in banal advertisements and in the fantasies of people whose daily struggles with physics center on properly tying a shoelace. Interestingly, Einstein described himself as “a man, a good European, a Jew.” For some reason, however, he felt compelled to omit two obvious aspects of his persona; that of being a scientist and that of being a musician. As he famously stated, “If I had not been a scientist, I would have been a musician. Life without playing music is inconceivable for me. I live my daydreams in music. I see my life in terms of music; I get most joy in life out of music.”

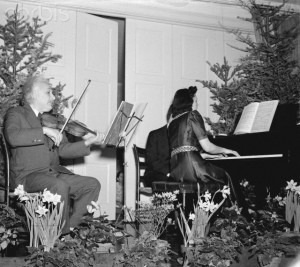

Albert Einstein and Gaby Casadesus Giving Recital

© digitalchemy.wordpress.com

Like every other boy growing up in a cultured and educated German family of Jewish origins at the turn of the century, young Albert started formal musical instruction. By all accounts, his mother Pauline was a talented pianist, and Albert took up the violin. Apparently, it was not easy for him to come to terms with the rudimentary technical aspects of his instrument, and he once is supposed to have thrown a chair in frustration. However, his musical universe started to come into focus when he discovered the music of Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart at the age of 13. In particular, he was fascinated with Mozart’s violin sonatas, a love he retained throughout the years. According to Einstein, Mozart’s music “was so pure that it seemed to have been ever-present in the universe, waiting to be discovered by the master.” As Leon Botstein rightly observed, Einstein’s partiality for Mozart was a search for “a purity of genre set against more Romantic, eclectic or contemporary musical tendencies.” In that sense, Einstein was simply part of a popular stream of modernism that was found through a purifying form of conservatism. It was Einstein’s second wife Elsa that connected her husband’s love for Mozart with his work in physics. “As a little girl, I fell in love with Albert because he played Mozart so beautifully on the violin. Music helps him when he is thinking about his theories. He goes to his study, comes back, strikes a few chords on the piano, jots something down, returns to his study.” There has been ample speculation that Einstein’s love of music somehow contributed to his scientific genius. Einstein himself did not publicly support these rather simplistic parallels, but it is nevertheless attractive to think that both Mozart and Einstein succeeded in unraveling the complexity of the universe. Einstein also worshipped Bach, and once reprimand an editor with the words, “I have this to say about Bach’s works: listen, play, love, revere — and keep your trap shut.” For obvious personal reasons, Einstein could not muster the same level of admiration for Richard Wagner. “I admire Wagner’s inventiveness, but I see his lack of architectural structure as decadence. Moreover, to me his musical personality is indescribably offensive so that for the most part I can listen to him only with disgust.

Artur Schnabel © www.jeunessesmusicales-mv.de

Once Einstein had established his renown as a physicist, he was frequently invited to perform at benefit concerts. Rather embarrassingly, a critic attending one such event, and unaware of Einstein’s real claim to fame wrote, “Herr Einstein plays excellently. However, his world-wide fame is undeserved.” Another critic sarcastically commented, “I suppose now Fritz Kreisler is going to start giving physics lectures.” Over the years, Einstein’s performing abilities have surely been exaggerated, but Leon Botstein reckons that his technical abilities ranked him as an accomplished amateur. This supposition is supported by Einstein’s friend Janos Plesch who wrote “There are many musicians with much better technique, but none, I believe, who ever played with more sincerity or deeper feeling.” It is also supported by a delightful little anecdote that exists in numerous delicious variations. In the 1920’s Einstein was invited to join a professional quartet during rehearsal. Apparently, he kept missing most of his entrances. The exasperated pianist, Artur Schnabel eventually turned to him and said: “For heaven’s sake, Albert, can’t you count?”

Sunday, December 12, 2021

Mealtime With Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart

by Georg Predota, Interlude

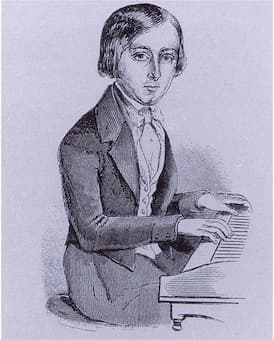

The young Mozart

Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart loved billiards, his pet starling, and food! Food was plentiful in Vienna during Mozart’s time, and a cheap and common meal would have consisted of two large meat dishes with soup, vegetables, bread, and a quarter liter of local wine.

With Mozart, Haydn, Beethoven and numerous other composers hanging around, Vienna was clearly a musical center. Concurrently, it was an epicurean center that created and established the Viennese cuisine we still enjoy today. Recipes for such fabled dishes as “Wiener Schnitzel, Tafelspitz, Kaiserschmarrn, and Sacher and Linzer Torte,” became formalized and circulated in a variety of cookbooks. And Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart was a good and happy eater. From a journey to Milan, his father Leopold writes to his wife, “We are in God’s hands wherever we are. Wolfgang will not ruin his health by eating and drinking. He is fat and in good health, and is merry and cheerful all day long.”

Liver Dumplings

During his adult life, Mozart started his day with hot chocolate and white rolls for breakfast, and habitually had a big pot of soup for lunch. And that apparently included a local Viennese specialty called “Kuttlflecksuppe,” which roughly translates to tripe soup. Mozart also enjoyed Sturgeon, a Flemish beef and beer stew called “Carbonnade” and the large neutered rooster called “Capon.” From his letters we also learn that he frequently dined on braised pigeons with chestnuts and almond casseroles, complemented by local wines and fruits. But his all-time favorite dish was liver dumplings with sauerkraut! The dumplings are made by mixing finely ground calf liver with egg, breadcrumbs, garlic, salt and an optional splash of milk. Once they have been shaped into little balls, the dumplings are dropped in beef broth and simmered partially covered for about 15 minutes. And we all know about sauerkraut! Mozart also loved pork cutlets. In a letter from 1791 Mozart writes to his wife, “What do I smell? Why, here is Don Primus with pork cutlets! Che gusto! Now I am eating to your health!” Given the composer’s love for pork it has recently been suggested that Mozart died from trichinosis caused by the parasitic worm Trichinella predominantly found in raw pork. Whether that is actually the case or not, the disease was certainly rampant in Vienna during Mozart’s time.

Friday, December 10, 2021

The Memory Game

by Frances Wilson , Interlude

Yuja Wang (without score!)

It’s one of the great romantic images, isn’t it? The solo performer, alone on an empty stage, faced with that huge black beast of a full-size concert grand piano, armed with nothing but his or her memory and willing, well-trained fingers.

There’s a lot of snobbery surrounding memorisation, and yet it’s one of the most absurd things pianists put themselves through. We have Clara Schumann and Franz Liszt to thank (or blame!) for the tradition of the pianist playing from memory, and both were significant in turning the piano recital into the formal spectacle it is today. Before the mid-nineteenth century, pianists were not expected to play from memory and playing without the score was often considered a sign of casualness, or even arrogance: Beethoven disapproved of the practice, feeling it would make the performer lazy about the detailed markings on the score; and Chopin is reported to have been angry when he learnt that one of his pupils was intending to play him a Nocturne from memory.

Few pianists today would dispute the legacy of Liszt and Clara Schumann, and now playing from memory is almost de rigeur, so much so that if you go to a concert where the pianist plays from the score, you may hear mutterings amongst the audience, suggesting the performer isn’t up to the job or has not prepared the music properly. Which is of course rubbish: sometimes, especially in contemporary or very complex repertoire, it is simply not possible to memorise all of it. Interestingly, memorisation has actually limited the range of repertoire performed in concert: many soloists won’t commit themselves to more than a handful of works each season because of the burden memorization places upon them (as pianists, we have to learn more than double the number of notes of any other musician!).

There are sound reasons for playing from memory and it should not be regarded simply as a virtuoso affectation (the ability to memorise demonstrates a very high degree of skill and application). It can allow the performer greater physical freedom and peripheral vision, more varied expression and deeper communication with listeners. But the pressure to memorise (a pressure which is imposed upon pianists from a young age and reinforced in music college or conservatoire) can also lead to increased performance anxiety – I have come across a number of professional pianists who have given up solo work because of the unpleasant pressure to memorise and the attendant anxiety. The late great Russian pianist Sviatoslav Richter gave up playing without the score when he reached his 60s as he felt he could no longer rely on his memory, and Clifford Curzon and Arthur Rubinstein both struggled with memorisation.

While each individual will have his or her own particular method of memorisation, pianists in fact utilise four types of memory, all of which must be employed when learning music:

Visual Memory: human beings use this part of their memory function to record large amounts of information, such as faces and colours and everyday objects. Music is made up of patterns and shapes, and the pianist uses visual memory to “picture” the score, as well as to recall the physical gestures involved in playing.

Aural/Auditory Memory: this is what enables us to sing in the shower! Music is an assortment of sounds, arranged in a certain order. The pianist uses aural memory to know he/she is playing the correct notes and to anticipate what he/she will play in the next few seconds.

Muscular/Procedural/Kinesthetic Memory: the ability to recall all the movements, gestures and physical sensations required to play music. Muscular or “procedural” memory is trained by repetitive practice: just as the tennis player practices his over-arm serve in exactly the same way each time to ensure a perfect delivery, so the pianist must employ repetitive practice to ensure the fingers land on the right notes every time.

Analytical/Conceptual Memory: the pianist’s ability to fully comprehend, absorb and retain the score through his/her intimate study and knowledge of it. This involves understanding structure, harmony, dynamics and nuances, phrasing, reference points, modulations, repetitions etc, as well as the context in which the music was composed, whether it is Baroque, Classical or Romantic, for example. This “total immersion” in the score should result in a rich, multi-layered awareness of it.

Many young students rely, often unconsciously, on auditory and visual memory, or on auditory and muscular memory, and many can play very competently from memory. However, to play expertly from memory, and to ensure that one’s ability to download and deliver music very accurately is completely secure, all four aspects of memory must be trained and maintained.

I go to many live piano concerts every year and I have noticed a growing trend: more solo pianists (Alexandre Tharaud is a notable example) are now using the score (accompanists and collaborative pianists tend to use the score, with the assistance of a page-turner, or the more modern alternative of an iPad or tablet with a score-reading app). It is possible to perform from the score and to deliver a quality performance which is rich in expression, gesture, and musicality. Well-managed page-turns, with the assistance of a discreet page-turner, should not detract from the performance, and after all, isn’t a concert fundamentally about communication, between performer, composer and audience? If you get that right, nothing else should matter.

Thursday, December 9, 2021

The origins of the ‘Twelve Days of Christmas’: the lyrics, numbers and timings explained

By Sophia Alexandra Hall, ClassicFM London

@sophiassocialsWe all know the ‘Twelve Days of Christmas’ song, what is the story behind those sometimes bizarre lyrics? Leaping Lords await...

Twelve days of Christmas? ...we sing about them every year. But this Christmas it might be time for a deeper dive. Let’s discover that incredibly generous ‘true love’ who bestows the bunch of daily bizarre gifts on the song’s protagonist.

Who gets their true love 8 maids [who are] milking [a cow]? and where do you even get eight milkmaids from? Are they there by choice? Do we need to call the police?

Keep hold of those gold rings, as we break down the story behind one of the season’s most iconic songs.

When are the twelve days of Christmas?

The twelve days of Christmas are sometimes also known as Twelvetide.

There is a raging debate as to when exactly Twelvetide starts. While some would suggest the first day of Christmas is Christmas Day itself (25th December), the majority see 26th December as day one, meaning magic number 12 falls on the 6th of January; the traditional Christian feast day of Epiphany.

While not a celebration in itself, these twelve days are embedded into the culture of multiple Christian nations.

In the UK and other commonwealth countries, the 26th December is commemorated as the national holiday Boxing Day, while the 6th January, is seen as the last day you can have your Christmas decorations up by many European countries. And if you don’t take them down, some people think it’s bad luck.

This period has been recognised as a festive and sacred season since before the middle ages, with the twelve days from Christmas to Epiphany having first been proclaimed as such all the way back in 567AD.

The English carol

The first appearance of this seasonal song was actually, not as a song at all, but as a rhyme.

These lyrics were published in England in 1780 without music, and many composers would go on to write tunes for the words over the next 100 or so years.

However, the melody we most associate with this song is derived from a 1909 arrangement of a traditional folk melody by English composer, Frederic Austin.

The twelve verse song, as published in 1909 with the folk melody, describes the following gifts which are given each day;

- A partridge in a pear tree

- Two turtle doves

- Three French hens

- Four calling birds

- Five gold rings

- Six geese a-laying

- Seven swans a-swimming

- Eight maids a-milking

- Nine ladies dancing

- Ten lords a-leaping

- Eleven pipers piping

- Twelve drummers drumming

Read more: The Twelve Days of Christmas, composed as a 12-tone masterpiece

So...what’s with the lyrics?

Some of the gifts given by the ‘true love’ are pretty self-explanatory. Five gold rings? Pretty cool gift. Three french hens? I've heard they lay delicious eggs, so that’s thoughtful.

But what could these strange gifts represent? Is there a deeper meaning?

Well in a theory debunked by the fact-checking website, Snopes, it has been suggested that the twelve days of Christmas song is a coded reference to important articles of the Christian faith.

The theory suggests that each gift represented a tenet of faith, and the song was sung by young catholics as a memory aid to remember various aspects of their religion.

According to this debunked-yet-interesting theory, the two turtle doves represent the Old and New Testaments, the six geese a-laying represent the six days of creation, and ten lords a-leaping represent the ten commandments. The ‘true love’ is meant to represent God and the gifts he bestows upon the baptised.

While a fascinating theory, it has been debunked as a potential lyrical origin story as there is no supporting evidence or documentation to suggest this was ever the case.

The claim also appears to date back to only the 1990s, meaning the theory’s roots are most likely founded in modern speculation.

Another, perhaps more credible theory for the origin story of the song, is that it was a memory game.

These types of songs were common in 1800s English playgrounds, and would normally involve children taking turns to sing all of the previously sung lyrics, before adding the next line. If someone got the lyrics wrong, there would usually be a forfeit.

This would explain the number of verses in the song, and the repetition of each previous gift in every new verse.

The Twelve Days today

Whatever the origins of the song, in modern-day money, you would be looking at spending around £30,900 on all of the gifts. This figure is courtesy of PNC, an American financial services group, who calculate an annual Christmas Price Index® for how much the total of the twelve gifts would be today.

Whether you’ll be spending a whopping 30 grand on some birds and musicians, or looking at a different range of Christmas presents for your beloved, make sure you’ve got these lyrics memorised so you can impress your true love with a perfect rendition of the twelve days tune.

And teach it to your children – it may help them on the playground during this Christmas season...

ANDREA BOCELLI

Wednesday, December 8, 2021

John Williams: his music and his life

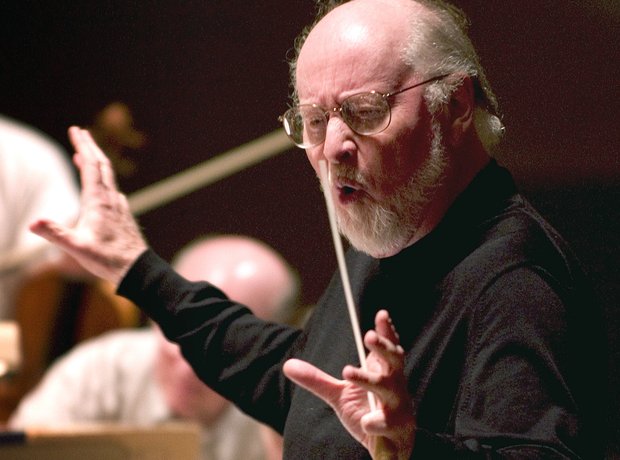

From writing the world's best-loved soundtracks - such as Star Wars and Harry Potter - to conducting the Boston Pops, John Williams is one of today's musical giants.

1. The force is with him

Born on 8 February 1932 in Long Island, John Williams has composed some of the most popular and recognizable film scores ever, including Jaws, the Star Wars films, Superman, the Indiana Jones movies, E.T., Jurassic Park, Schindler's List, Saving Private Ryan and three Harry Potter instalments. He has won five Oscars, four Golden Globes, seven BAFTAs and 21 Grammys. With 48 Oscar nominations, he is second only to Walt Disney as most nominated person ever.

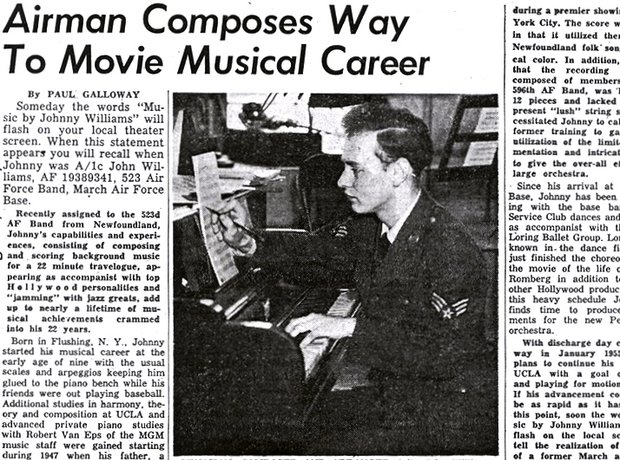

2. Aspiring young musician

John Williams grew up in a musical family; his father was a jazz percussionist. Young John attended UCLA while studying composition privately with Mario Castelnuovo-Tedesco. Drafted in 1952, Williams spent three years conducting and arranging music for the U.S. Air Force Band. After his service ended, Williams moved to New York City and entered Juilliard where he studied piano.

3. Legendary piano riff

Williams worked as a pianist in jazz clubs and eventually studios, most notably for the brilliant Henry Mancini. 'Little Johnny Love Williams' played the famous piano riff on the groundbreaking Peter Gunn theme. Williams went on to be music arranger and bandleader for a number of albums for singer Frankie Laine.

4. Composing TV classics

Williams returned to L.A. from New York. There he began working as an orchestrator at film studios with such legends from Hollywood's Golden Age as Franz Waxman, Bernard Herrmann, and Alfred Newman. He also developed his skills writing the music for hit 1960 TV shows, Gilligan's Island, Lost in Space, The Time Tunnel and Land of the Giants - pictured.

5. Academy Award recognition

John Williams received his first Academy Award nomination in 1967 for Valley of the Dolls. He was nominated again for Goodbye, Mr. Chips. He won his first Oscar for musical direction for Fiddler on the Roof. High profile scores for 1970s disaster movies followed - The Poseidon Adventure, The Towering Inferno and Earthquake.

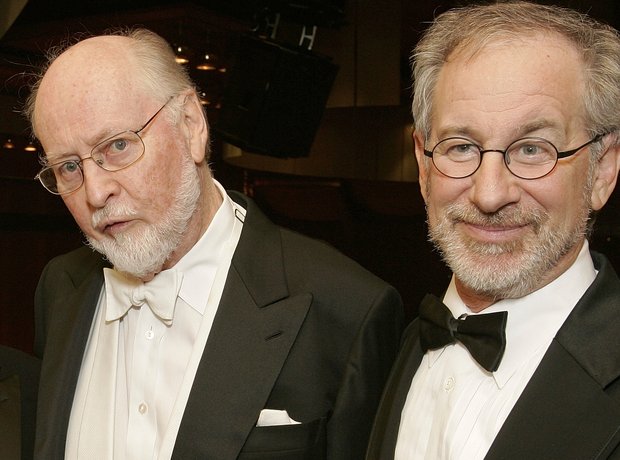

6. An extraordinary partnership

In 1974, a young director called Steven Spielberg approached Williams to compose music for his film, The Sugarland Express. They teamed up again the following year for Jaws. The threatening shark motif, two low notes played alternately on the tuba, has since become synonymous with sharks in general and danger at sea. Spielberg and Williams have gone on to work on more than 20 films together, most recently War Horse, Lincoln and The Adventures of Tintin.

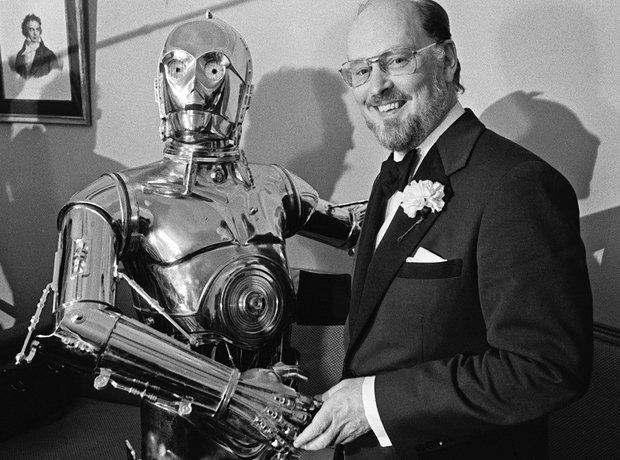

7. A galaxy far, far away...

Spielberg recommended Williams to his friend George Lucas, who needed a composer for Star Wars. Williams delivered a grand symphonic score in the style of Hollywood's swashbucklers of the 1930s and 1940s. The soundtrack remains the best-selling non-pop record of all-time - and Williams won another Oscar for Best Original Score. He was also nominated for the follow-up scores for The Empire Strikes Back and The Return of the Jedi.

8. At the peak of his powers

The late 1970s and early 1980s saw Williams at the peak of his powers and success. He scored Superman in 1978, followed by The Empire Strikes Back (1980), and Raiders of the Lost Ark (1981), created by George Lucas and directed by Spielberg. Williams' rousing Raiders March theme has defined the character of Indiana Jones and become a concert hall favourite in its own right.

9. Boston Pops star

From 1980 to 1993, Williams was Principal Conductor of the Boston Pops Orchestra. He is now its Laureate Conductor, leading the orchestra on several occasions each year, particularly during their Holiday Pops season and a week of concerts in May. He conducts an annual Film Night at both Boston Symphony Hall and Tanglewood.

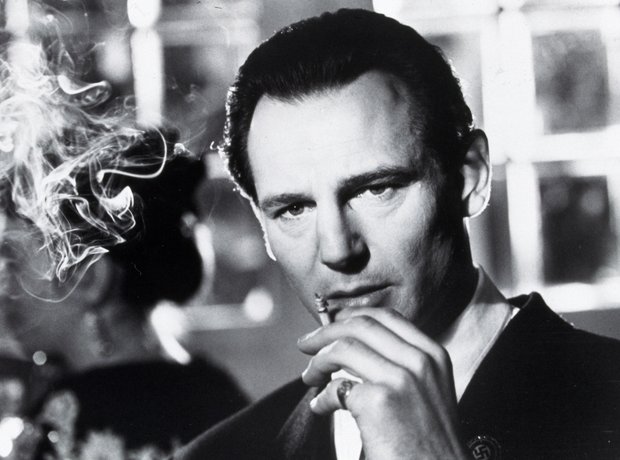

10. Schindler's List

Considered by many to be the finest film score of recent decades, Schindler's List followed hot on the heels of Spielberg and Williams' collaboration on Jurassic Park - and it couldn't be more different. When he first saw the film, the composer told the director: 'You need a better composer than I am for this film.' Spielberg replied, 'I know. But they're all dead!' For the soundtrack Williams, following Spielberg's suggestion, hired the great violinist Itzhak Perlman. The film's main theme, played with such passion and emotional intensity by Perlman, is heartbreakingly simple and touching. For Schindler's List, Williams won his fifth Oscar.

omposer John Williams awarded RPS Gold Medal...

... for introducing millions to orchestral music

|  |

‘He has dedicated his life to ensuring orchestral music continues to speak to and captivate millions of people worldwide.’

Internationally treasured composer John Williams, 88, is the recipient of this year’s RPS Gold Medal.

The legendary film maestro, who composed the enduring music for Star Wars, Harry Potter, Schindler’s List and many more, won the coveted award at the 2020 Royal Philharmonic Society Awards, for introducing millions to orchestral music.

His win, one of the highest honours in music recognising outstanding musicianship since 1870, was announced during a digital broadcast on 18 November featuring performances filmed at London’s Wigmore Hall.

Accepting the medal via video, Williams said: “To receive this award is beyond any expectation I could possibly have. For any composer to be able devote his or her life entirely to the composition of music is very fortunate indeed.”

Director Steven Spielberg presented a special congratulatory message to his long-time collaborator via video message, saying: “John, you have brought the classical idiom to young people all over the world through your scores, and through your classical training and your classical sensibilities. You are in the DNA of the musical culture of today.”

In his wonderful introduction to Williams’ win, which was determined by the RPS Board and Council and voted for by RPS members, RPS chairman John Gilhooly said:

“Some of us are born into classical music, never recalling a time without it. Others are drawn to its magic by the spell that orchestras cast in bringing soul, drama and humanity to motion pictures.

“The recipient of this year’s RPS Gold Medal has dedicated his life to ensuring orchestral music continues to speak to and captivate people worldwide in this way. Aged 88 and still at work, he is an international treasure, writing score after score of sophistication and impact, many transcendent of the films for which they were written.”

Elsewhere, cellist Sheku Kanneh-Mason was presented with the Young Artists Award for “captivating listeners worldwide”.

Welsh soprano Natalya Romaniw received the Singer Award, while the Scottish Ensemble received the Ensemble Award for their innovation in their 50th birthday year.

(C) 2020 by ClassicFM London

Unlike many contemporary composers, John Williams is a household name, even among families who aren't classic music buffs. To date, his award stats seem inconceivable, even to the most aspiring of professional composers. They include 25 Grammy Awards, seven British Academy Film Awards, five Academy Awards, and four Golden Globe Awards (and more to come, we would imagine).

A well-published John Williams quote (filmtracks.com) states, "So much of what we do is ephemeral and quickly forgotten, even by ourselves, so it's gratifying to have something you have done linger in people's memories." Based on that statement, this famous musician, composer, conductor, and music producer must be one gratified human being.

John (Johnny) Williams II: The Basics

We can't post an Artist Spotlight without capturing some of the basic biographical details. But, as we know, there is so much more to any human than birth dates and accolades. Therefore, the second section of this post focuses on facts you may not know about one of the 20th/21st centuries' most famous and well-loved composers.

The Early Years

John (Johnny during his younger years) Towner Williams II was born on February 8, 1932, making him almost 90 years wise today. He was born in Queens, New York, to parents Esther (née Towner, hence his middle name) and Johnny Williams. His father was a talented jazz percussionist who played with the Raymond Scott Quintet. Later on, after the family's move to Los Angeles in 1948, his father worked as a recording artist and a studio musician for both radio and films.

Williams's mother was originally from Maine and grew up in a family that owned a department store. Her father was also a carpenter and cabinet maker. As a result, John Williams, the composer, felt his life exemplifies both the musicianship and the strong work ethic that defined his formative years and family culture.

As is the way of many professional composers, Williams quickly became poly-instrumental. He began playing the piano at age six. By the time he left grade school, Williams was proficient on the bassoon, cello, clarinet, trombone, and trumpet. Eventually, Johnny-now-John attended UCLA, where he studied composition.

Williams' later years

In 1951, John Williams got drafted into the military, where he served in the U.S. Air Force Band as a pianist, brass player, and conductor. Upon his release from the service in 1955, he was accepted into Julliard. At first, Williams planned to become a concert pianist but eventually turned his sights to composition. He continued his composition studies at the Eastman School of Music and, upon graduation, Williams began working as an orchestrator in film studios.

That initial post-graduate job led to Williams's career as a world-renowned film score composer. However, it's impossible to narrow down his "best-known works" because the entire list is recognizable, including:

Jaws (1975)

Superman - The Movie (1978)

The Empire Strikes Back (1980)

Raiders of the Lost Ark (1981)

E.T.: The Extra-Terrestrial (1982)

Jurassic Park (1993)

Schindler's List (1994)

Seven Years in Tibet (1997)

Saving Private Ryan (1998)

The first three Harry Potter films (2001, 2002, and 2004)

All of the Star Wars films

(Wikipedia's complete list of compositions by John Williams)

We could go on, but you get the point. He also served as music director and laureate conductor of one of the country's treasured musical institutions, the Boston Pops Orchestra.

In our post, Insights From the World's Best Film Score Composers, we quoted John Williams saying, "I think the biggest single mission perhaps of the filmmakers and myself is to try to seek universalisms in the story, in the music, and in the emotions." (Source: Gramaphone). His laudable career exemplifies John Williams's ability to do just that.

10 Fun Facts

Now, as promised, we'd like to break away from the basic details and leave you with ten fun facts you might not have known about John Williams.

He's been nominated for 52 Academy Awards, making him the second-most nominated person after Walt Disney.

You can hear some of his early professional piano playing in the movies "Some Like it Hot (1959)" and "To Kill a Mockingbird (1962)."

Williams "allowed" Steven Spielberg to play clarinet, which he'd learned to play in high school in the band street scene. The dailyjaws.com website quotes Williams saying that Spielberg "added the right amateur quality to the piece" (sorry, Steven).

He paid his way through graduate music school, working as a nightclub jazz pianist and a bandleader called "Little Johnny Love."

In an interview with businessinsider.com, Williams admitted that he's never seen a single "finished" version of the Star Wars Films.

Technology is not his thing. Williams composes his scores at a desk with a pencil and paper, with his adjacent Steinway piano as a companion. John Williams has this to say about technology, "I have not evolved to the point where I use computers and synthesizers. First of all, they didn't exist when I was studying music, and luckily, mercifully, I have been so busy in the interim years that I haven't had time to go back and retool. And so my evolution, in very practical terms, i.e. piano and pencil and paper, has not changed at all." (Grunge)

John Williams's son, Joseph, was the lead singer of the band Toto, most famous for their songs, "Africa" and "Rosanna."

While best known for his film scores, a composer is a composer through and through. Williams has also composed concert hall performances that include two symphonies and various concertos for horn, cello, clarinet, flute, violin, and bassoon. Watch Yo-Yo Ma performing Williams's Concerto for Cello and Orchestra.

The iconic first three notes of the Jaws theme song (which Spielberg thought were a joke at first) have become the most famous musical introduction in history after the beginning of Beethoven's Fifth Symphony.

Two of his first Academy nominations were for movies you've probably never heard of: Valley of the Dolls (1967) and Good-Bye, Mr. Chips (1969).

At a sharp and still-composing 89 years old, John Williams is a musician, composer, producer, and conductor who deserves every bit of the respect and accolades he's received. We look forward to what this soon-to-be nonagenarian composes next.