It's all about the classical music composers and their works from the last 400 years and much more about music. Hier erfahren Sie alles über die klassischen Komponisten und ihre Meisterwerke der letzten vierhundert Jahre und vieles mehr über Klassische Musik.

Popular Posts

-

by Hermione Lai It’s not really common knowledge, but Georges Bizet was an absolutely brilliant pianist. He entered the class of Antoin...

-

by M aureen Buja With its full title, La mer, trois esquisses symphoniques pour orchestre (The sea, three symphonic sketches for orchest...

-

By Georg Predota “Blind Tom,” as he was generally known, was born into slavery in Columbus, Georgia in 1848. He was sold with his family du...

-

by Emily E. Hogstad June 7th, 2025 The great composers left behind more than just great music: they also left behind advice for their fe...

-

774,844 views May 29, 2024 #pierobarone #ignazioboschetto #tuttiperuno Social • Instagram: @ignazioboschetto.italy • Tiktok: @ignazi...

-

Join the cast of Les Misérables' 25th anniversary concert as we take a look at the first & last songs from the live musical with our...

-

182,711 views Feb 22, 2025 #WendyKokkelkoren #Goosebumps #Ballads 00:00 - 05:00 Hallelujah 05:01 - 09:38 I Will Always Love You 09...

-

Francisco Beltran Buencamino Sr Francisco Beltran Buencamino was born on the 5th of November, 1883 in San Miguel de Mayumo, Bulacan. He is...

-

930,887 views Jun 7, 2025 #futureofclassicalmusic #virtuosos Subscribe to @Virtuosos_Talent_Show | / virtuozok / virtuosos_t...

Übersetzerdienste - Translation Services

Total Pageviews

Friday, November 15, 2024

Daniel Reuss on Frank Martin (60 seconds)

Sigurd Raschèr: King of Sax

By Georg Predota, Interlude

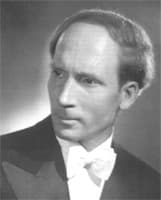

Sigurd Raschèr

Hector Berlioz wrote, “I find the main advantage of the saxophone to be the wide variety and beauty of its expressive possibilities. Sometimes low and calm; then passionate, dreaming, and melancholy; at times as gentle as the breath of an echo; other times like the vague, lamenting wail of wind in the trees.” The instrument was used in French opera for special effects and to add orchestral colour. It eventually became an essential member of jazz ensembles and swing bands. However, there is plenty of concert music in the classical idiom for the saxophone, and most of it was inspired and composed for Sigurd Raschèr (1907-2001).

Adolphe Sax, 1850s

Sigurd Raschèr was born in Germany to an American military physician. Initially, he studied the clarinet, but in order to become part of a dance band, he started to play the saxophone. “As I did this for a couple of years,” he writes, “I became more and more unsatisfied. I started to practice furiously and slowly found out that it had more possibilities than was usually thought.” After moving to Berlin, he met the composer Edmund von Borck, who composed a concerto for him in 1932. The work was first performed at the General German Composers Festival in Hanover and was considered a huge success. In fact, the Berlin Radio Symphony Orchestra picked up the piece for a performance, and this was followed by performances in Strasbourg and in Amsterdam. Raschèr was lauded for his brilliant agility, sweetness of tone and musical sensibility and for substantially extending the range of the saxophone by more than an octave.

Contemporary reviewers wrote, “Raschèr’s mastery of his instrument and the control of an almost inaudible pianissimo is phenomenal. His cantabile has real beauty, and his dexterity must be almost unequalled.” Paul Hindemith (1895-1963) had been interested in the sound of the saxophone in the 1920s, and he included the instrument in the scores for his theatre works. It features prominently in his opera Cardillac, the story of a goldsmith who is uncontrollably in love with the jewellery he creates and ends up murdering the people who purchase them. In that score, the tenor saxophone, with its “vaguely erotic connotations of timbre, represents the goldsmith’s secret passion.” Raschèr approached Hindemith for a dedicated composition, and Hindemith responded with his Concert Piece for Two Alto Saxophones in 1933. Hindemith told his publisher that he had “written very quickly, a gymnastic exercise, an extensive saxophone duet.” As Raschèr had secured an appointment to teach at the Royal Danish Conservatory in Copenhagen, he took the Hindemith manuscript with him. Raschèr and his daughter Carina premiered the piece only in 1960.

A Yamaha saxophone

Raschèr’s engagement in Denmark was quickly complemented by an appointment in Malmö, Sweden. He continued to tour extensively, performing concerts in Norway, Italy, Spain, Poland, Hungary, and England. While concertising in England, Raschèr met Eric Coates (1886-1957), a leading violist, conductor and popular composer of light music. During his early career, Coates was primarily influenced by the music of Arthur Sullivan, but eventually, his musical style evolved “in step with changes in musical taste.” Coates primarily composed orchestral music and songs, and he never really wrote for the theatre and only occasionally for the cinema. In his Saxo-Rhapsody for Raschèr, however, he incorporated countless elements derived from jazz and dance-band music.

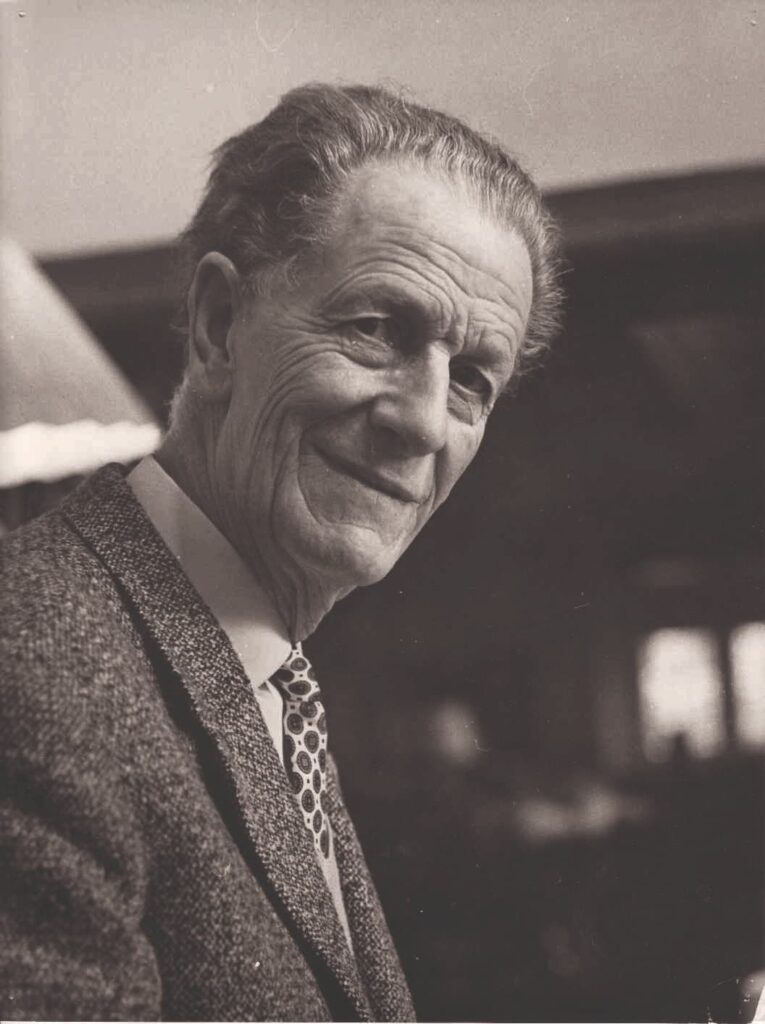

Jacques Ibert

In April 1936, Raschèr participated in the 14th Festival of the International Society for Contemporary Music (ISCM), and he premiered the Concertino da Camera by Jacques Ibert (1890-1962). Ibert was of the opinion that high-quality classical music does not always have to be deadly serious. He summed up his general approach and attitude towards music in a few words. “I want to be free and independent of the prejudices which arbitrarily divide the defenders of a certain tradition and the partisans of a certain avant-garde.” As such, Ibert rejected the two artistic trends that dominated the French musical scene at this time: French Impressionism and German Expressionism. Ibert only wrote music that he was happy to listen to himself. His Concertina da Camera is scored for alto saxophone and 11 instruments. The composer takes advantage of a number of contemporary musical trends, including the prevailing jazz and blues influences of his day.

Frank Martin

The Swiss composer Frank Martin (1890-1974) initially followed the wishes of his parents and studied mathematics and physics. Concordantly, he took private music lessons with Joseph Lauber but never studied at a conservatory. Nevertheless, his music shows a clear awareness of the various strands of contemporary music. We find serialism, extended tonality, free atonality, neo-classicism and rhythmic experimentations. Martin is indebted to both French and German musical styles, and his Saxophone Ballade, dating from 1938, sounds “chromatic melodies, jabbing rhythms and a predilection for sections in a playful and often syncopated compound time, but with a high level of dissonance to excite the ear.”

Raschèr made his American début in 1939, and he played with the Boston SO and the New York PO, “the first saxophonist to appear as a soloist in a subscription concert given by either orchestra.” He would subsequently perform with more than 250 orchestras worldwide. A historian writes, “Throughout the middle decades of the twentieth century, a preponderance of the significant new saxophone solo and chamber repertoire would appear with the familiar dedication to Sigurd M. Raschèr, the outcome of not just his ongoing commitment to motivating some of the world’s finest composers, but also in part the result of genuine close friendships he developed with so many… And it is not without significance that among all the pieces written for and dedicated to him during his life, not one was commissioned. He inspired new music, he never needed to purchase it.” Case in point, the American composer and educator Maurice Whitney (1909-1984) was Raschèr’s personal friend, and the Intro and Samba was freely composed and dedicated to him in 1951.

In 1951 Sigurd Raschèr approached William Grant Still (1895-1978) for a saxophone commission. He writes, “I know many of your works, as every educated musician does. And many times, I did think: Still would be a composer who could write something for the Saxophone that would be truly in the nature and style of the instrument… I am convinced that composition from your hand would meet with very considerable interest, wherever performed.” Still completed the commission in 1954, and “because of its apparent simplicity and absence of technical virtuosity,” his Romance was initially overlooked by many recitalists. In the manner of Franz Schubert, Still introduces several phrases that are restated a number of times. “The challenge for the interpreter is to reveal fresh layers of meaning with each repetition, thus providing the listener with ample opportunity to experience the subtle tonal shadings and contrasts available from the saxophone.” The orchestra setting, in turn, reflects Still’s experience of working as a composer for many Hollywood films and as a creator of television scores.

Henry Cowell

Raschèr stirred up a good bit of controversy by advocating that the saxophone used in classical music should sound like the inventor Adolphe Sax had intended. Sax specified that the interior of the mouthpiece should be large and round. With the advent of big-band jazz, however, saxophonists began to experiment with different shapes to “get a louder and edgier sound.” As a result, narrow-chamber mouthpieces also became common use by classical saxophonists. Raschèr was emphatic that the sound produced by modern mouthpieces provided the jazz player with a loud, penetrating sound but that “this particular sound was not appropriate for use in classical music.” Because the narrow-chamber mouthpiece became universally popular, Raschèr engaged a manufacturer to make official “Sigurd Raschèr brand” mouthpieces; they are still produced today.

Sigurd Raschèr with Carl Anton Wirth

The Idlewood Concerto by Carl Anton Wirth (1912-1986) was first performed on 22 October 1956 by the Chattanooga Symphony Orchestra. A critic wrote, “The overall impression of this work is of peaceful repose and meditation. The emphasis is less on rigid tonality and rhythm than on melody. The concerto develops from a melodic seed and proceeds without redundancy and complex variations. It is fresh and of lean construction. There is nothing superfluous in the progression and development of ideas.” Raschèr taught at the Juilliard School, the Manhattan School, and the Eastman School of Music. In 1969, he founded the Raschèr Saxophone Quartet, which commissioned and recorded many works by composers such as Berio, Glass, and Xenakis. In all, 208 works for saxophone are dedicated to him, and we should rightfully consider him the “King of Sax.”

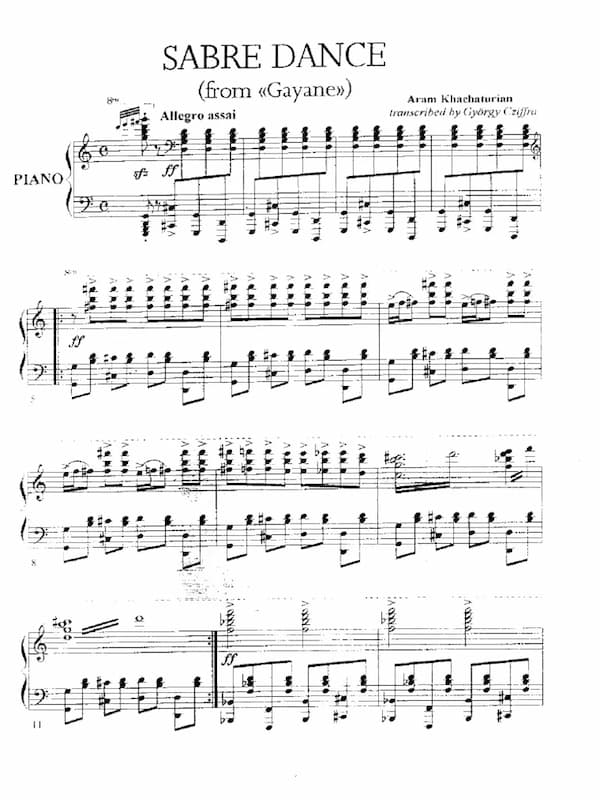

György Cziffra: Transcriptions and Paraphrases

by Georg Predota, Interlude

Childhood

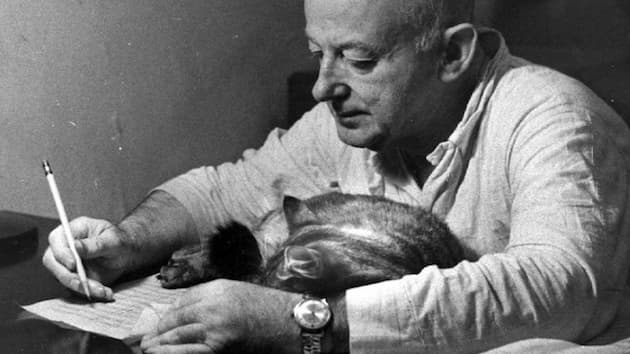

György Cziffra

Much has been written about his growing up in dire poverty on the outskirts of Budapest and his incredible musical talent on display at an early age. To be sure, the origins of his improvisational art can be traced back to his childhood and his ability to learn music without scores. Essentially, he mimicked the piano playing of his sister and repeated and improvised over tunes sung by his parents. “Thanks to the Strausses, the Offenbachs, and many others,” he later writes, “by the time I was five years old, improvisation at the piano became basically my only daily practice. It was more than mere pleasure; I had the power in my hands, and whenever I liked, I could break away from reality.”

Bar Pianist

Forced to contribute to the meagre household income of his family, Cziffra initially earned money as a child improvising on popular music at a local circus. In the 1930s, and during his studies at the Franz Liszt Academy, however, Cziffra decided to earn money by performing as a bar musician. As he later wrote, “I met some bar musicians, and they gave me some good advice as to how to enter the realm of popular music. Later, they invited me to listen to them play, and slowly, I transformed into a pop musician and, for a while, this was my real profession.” While it was still his ambition to become a concert pianist, Cziffra enjoyed improvising and started to fashion a number of transcriptions of popular American songs and film scores.

Process of Improvisation

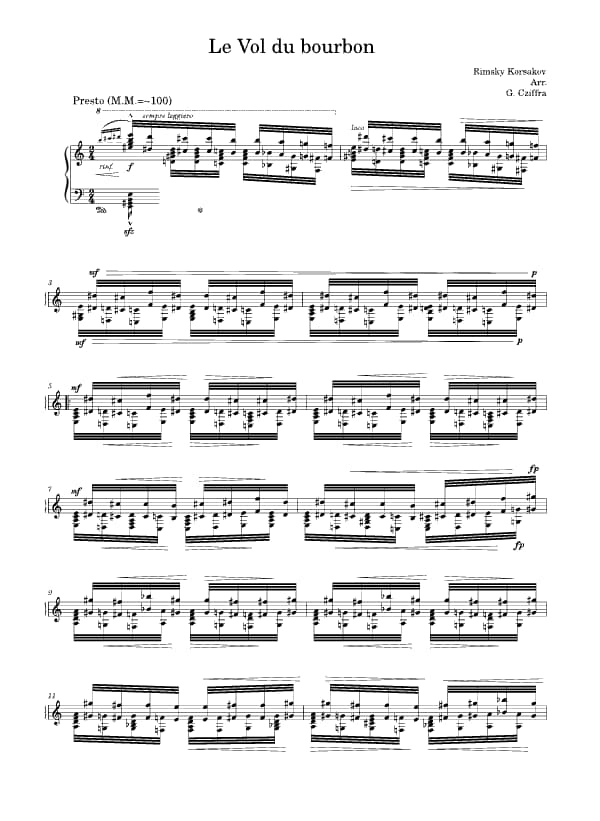

György Cziffra’s ‘Flight of the Bumblebee’ Transcription

He greatly enjoyed working in bars and taverns, and everybody knew him for his marvellous improvisations, which went from jazz, the fandango, and the czardas to the pasodoble. As he wrote, “I ended up dividing the nights between several lucrative places, spending two hours or so at each.” Between 1947 and 1950, Cziffra went on European tours with a jazz band, and in his autobiography, he described the process of improvisation.

“While I give myself over completely to the moment of inspiration, while I give the field of form and theme over completely to my imagination, I always try to maintain a discipline of my thoughts on the following two-three measures so that my hands can follow the path of my vision. The practice of this, at one-time tender and at another time enchanting, made it possible for me to discover the future form of piano performance in the moments of creation.”

First Performances

He quickly became recognized as a superb jazz pianist and virtuoso, and his performances soon became legendary. And in the footsteps of his hero Franz Liszt, Cziffra improvised dazzling fantasies on opera themes. From his earliest concert appearances, Cziffra wanted to finish a recital with “a short piece, that personally, could stand alone, and which was not prepared for eternity. When I improvise, I feel as if I become one with myself, and my body is freed from all earthly pain. It is truly a process of going beyond my talents, which makes it possible on each occasion to step over the known boundaries of the technical side of the piano performance.”

His career was on the verge of collapsing as Cziffra was imprisoned and subject to hard labour after attempting to flee Hungary in 1950. He was tasked with transporting blocks of stone and needed four months of physiotherapy after leaving prison in order for his fingers, swollen by work of a very different nature, to grow used to the piano again gradually. Cziffra’s first concerts after his release from prison were, to quote the pianist, “so dull as to verge on the incompetent. Fortunately, the transcriptions and improvisations I played as encores at the end of each recital compensated for the rest and shook my audience out of their apathy. These intense moments were like the ecstasy of love. One critic went so far as to say that this was the mastery not of a pianist but of the pianist of one’s dream.”

Success in the West

György Cziffra

When Cziffra made his Paris debut in 1956, he was hailed as “the most extraordinary pianistic phenomenon since Horowitz… Probably the only one of his Generation who can give each note a different colouration without ruining the continuity of the work he is performing.” One performance review even carried the headline, “Franz Liszt has arisen from the dead in a demonic experience, eliciting the landscape and soul of Hungary like a vision in drama and transfiguration.” However, not everybody was enthralled. His recitals featuring his own brilliant paraphrases were considered “brilliantly vulgar confections.” Cziffra himself said about his playing, “I became the profession’s Antichrist due to my improvisations, which multiplied the difficulties ten times over.”

Virtuosity

It was readily assumed that Cziffra’s transcriptions were simply composed for the sake of virtuosity. However, as has been pointed out, the most dazzling passages were born from the composer’s extreme intensity of expression, and the fiery passages were motivated by inner musical force. Cziffra believed that technical mastery should never be displayed for its own sake but rather made subservient to a powerful emotional intellect and a cultured mind. He never accepted praise for his phenomenal technique and sharply reproached admirers, “I don’t care about technique. What you call technique is simply an expression of feeling.”

Franz Liszt

György Cziffra’s ‘Sabre Dance’ Transcription

During a radio interview in 1984, Cziffra spoke about his close spiritual and artistic connection to Franz Liszt. “I started piano similarly to Liszt at a very early age, and I was making people happy with my improvisations, just like him. And, well, I think that I wasn’t too much below his capabilities in this field. This is not the question of immodesty or modesty; this I know because I was able to improvise in such a way those days that I could think four measures ahead. And I realise that very few people are able to do this. This is similar to a chess game, where one player is playing with twelve others simultaneously. By the time my hands arrive somewhere, my brain has already gone further.”

“And this is perhaps the most difficult thing about it. This is why when I make sound recordings improvising on certain melodies, numerous wrong notes happen, and mistakes; my hands cannot follow the outrageous speed that my brain commands. And at the same time, I shape the form of the piece as well. I am not only interpreting, but I am creating the actual piece at the moment. So, I think I am also a creator from another respect, certainly not to such extent as Franz Liszt was, but some congenial trait we do share.”

Notating Improvisations

Improvising is one thing; committing these flights of fancy and inspiration to paper is another. As Cziffra explained, “to put on paper the uniqueness of the improvisational form is extremely difficult… One needs an ear and untiring patience to put these improvisational sessions on paper.” A good many pianists have tried, and even more have failed and left the task unfinished. “But then my son George said that he would like to give it a try. With a tremendous amount of energy and enthusiasm, he took on the work.”

“Slowing down the tape in both directions, George wrote down the place of each sound, and slowly, after a point, he was able to give form to a certain amount of my musical creations. Finally, I too became involved in writing down the musical notes, which now turned into true compositions, which mirrored my thoughts and emotions.” Cziffra was certainly hoping that the pages of his published transcriptions would open the door to new possibilities and encourage a less stereotypical and more personal approach to performances of classical piano music.

Historical Legacy

Monument of György Cziffra in Budapest

Cziffra’s transcriptions and paraphrases left a dazzling record of his seemingly superhuman power. However, at the height of his popularity in the 50s and 60s, he seemingly vanished due to personal tragedy and changing tastes and fashion. He was frequently accused of using composers as a springboard for personal excess and idiosyncrasy, and audiences became weary of Romantic exaggeration and “turned elsewhere in search of greater depth and spiritual refreshment.”

His public image has always been highlighted by the recognition of his prodigious pianistic abilities and achievements. Yet, his critics always saw him as little more than a technician or notable interpreter of Liszt. Indifference to his unique powers has become almost commonplace, and in some quarters, he was even vilified. A French reviewer wrote, “when one plays like this, the best thing to do is to commit suicide.”

Critical Assessment

To be sure, Cziffra could play with pure elegance and simple, direct expression, but he inevitably polarised critical opinion and aroused stormy controversy. A critic wrote, “Cziffra could never play louder without getting faster,” and this particular shortcoming was attributed to haphazard and ill-disciplined technique. As you might well imagine, Cziffra wasn’t particularly enamoured with critics either, calling them “carrion beetles of the mind… easily recognized by their boundless pride and pathetic intellect.” To be sure, Cziffra’s ample use of rubato and variable tempi did not agree with current concert practice “but were the mark of artistic freedom and individuality of earlier times.”

The French-Cypriot pianist Cyprien Katsaris explained in a 2012 interview, “Cziffra had that terrible label as a circus-virtuoso pianist and very few people were willing to speak openly about all the good things about him. I think this is absolutely insane… He used his incredible virtuosity in an expressive way – whether it was revolt, whether it was anger, tenderness, or serenity. He was able to do so much with the wide range of whatever he played.” Cziffra was much more than a mere virtuoso, and his lyricism was sublime and his “personal commitment and distinctive musicianship reveal themselves in a number of fine recordings of keyboard music by C.P.E. Bach, Domenico Scarlatti, François Couperin, Johann Tobias Krebs, Jean-Philippe Rameau, Jean-Baptiste Lully, Mozart, and Clementi.”

His performances were always characterised by an unconditional spontaneity and the impulsiveness of the moment, and many critics denied him the ability “to interpret works that are less virtuosic in a coherent and true-to-the-text manner.” For Cziffra, “the interpreter’s role in society is like a keepers’ watching over people’s emotions to prevent them from being worn away by a soul-destroying everyday existence…Finally, my virtuosity no longer prevented people from seeing the wood for the trees.”

Thursday, November 14, 2024

Classical music is far from boring

"Classical music is far from boring - it has all the blood, energy, the sinister dark side, rhythm that rock music has, and all the refined, subtle sensuality that one can ask for."- Yuja Wang

12 best movie adaptions of musicals, ranked

7 November 2024, 14:24

By Will Padfield

We take a look at the greatest film adaptations of musicals across the eras.

There is nothing quite like the thrill of Broadway, the bustle of the West End, the atmosphere of anticipation before the curtain rises on a top-tier musical. For more than half a century, film producers and directors have tried to translate this feeling onto the big screen.

From the streets of 50s New York to the epic panorama of the Austrian Alps, we count down 12 of the greatest film adaptations of musicals.

A Funny Thing Happened on the Way to the Forum (1966)

Zero Mostel reprieved his stage role for the film adaption of this wild romp, inspired by the farces of ancient Rome. It has all the ingredients required for an entertaining film: a ridiculous plot, cross-dressing, and a brilliant score by the late great Stephen Sondheim.

Director Richard Lester perfectly adapts the mayhem of the original production to the screen, bringing Rome to life. Whilst songs such as ‘Everybody Ought to Have a Maid’ at first glance might seem a little dated, they offer a hilarious and astute critical commentary on 60s American life – a world of Don Draper-style executives – in a way which few other musicals of the time were able to do so effectively.

A Funny Thing Happened on the Way to the Forum (1966) - Comedy Tonight Scene (1/10) | Movieclips

Les Misérables (2012)

Do you hear the people sing? Well, we almost didn’t, as following the release of the stage musical in 1980, a film adaptation faced numerous setbacks, as the rights were passed on to several major studios, and various directors and actors were considered and disregarded.

The wait was worth it though, as this film turned out to be epic. The cast list reads as a who’s-who of Hollywood A-listers, all piling in to showcase their (ahem) ‘vocal talents’.

Les Misérables (2012) - Master of the House Scene (3/10) | Movieclips

My Fair Lady (1964)

“Few genres of films are as magical as musicals, and few musicals are as intelligent and lively as My Fair Lady," opined critic James Berardinelli about this fantastic adaptation.

Staring Audrey Hepburn – who replaced Julie Andrews from the stage musical – Rex Harrison and directed by George Cukor, the streets of London are brought vividly to life, supported by the full armoury of Warner Bros.

MY FAIR LADY | Official Trailer | Paramount Movies

Sweeney Todd (2007)

Dark, brooding and frankly disturbing, the Dickensian universe is brought to life in this gothic slasher musical by Sondheim.

Depp and Bonham Carter are at their villainous best, and Alan Rickman completely inhabits the role of Judge Turpin. Sondheim admitted that the film version differed significantly from the stage production, but in his own words, “if you just go along with it, I think you'll have a spectacular time”.

Sweeney Todd (7/8) Movie CLIP - By the Sea (2007) HD

Oklahoma! (1955)

With a plethora of show-stopping tunes, including ‘Oh, what a Beautiful Mornin’’, ‘Surrey with the Fringe on Top’ and ‘People Will Say We’re in Love’, to name a few, this classic Rodgers and Hammerstein wartime hit was adapted into an all-singing, all dancing technicolour blockbuster in 1955.

Featuring some of the era’s biggest stars, such as Gloria Grahame and Gordon MacRae, Oklahoma! was a critical and commercial success picking up a rave review from The New York Times and winning a host of awards. In 2007, Oklahoma! was selected for preservation in the United States National Film Registry by the Library of Congress as being “culturally, historically, or aesthetically significant”.

The Surrey With The Fringe On Top

Fiddler on the Roof (1971)

Containing some of the catchiest melodies written for a musical, Fiddler on the Roof received its Hollywood calling in 1971. Like the best adaptations, it manages to retain the feelings of intimacy from the original stage production, but with the added depth offered by filming on location. Chaim Topol – who plays Tevye – carries the show, with a multi-faceted performance that shows Tevye’s inner struggle and conflicts, pitted against a brutal world descending into the horrors of the 20th century. This was also the film that won John Williams, later of Jaws and Harry Potter fame, his first Academy Award.

Fiddler on the Roof (10/10) Movie CLIP - The Bottle Dance (1971) HD

Guys and Dolls (1955)

Featuring an incredible cast including Marlon Brando AND Frank Sinatra, this film – again from 1955 – hits all the right notes. Set on the streets of New York, Sinatra plays Nathan Detroit, a well-meaning small-time criminal gambler, who bets the mysterious Sky Masterson (Brando) that he can’t take Sister Sarah Brown to Havana on a date.

Sinatra is on top form here, elevating Frank Loesser’s glittering music, which gets a suitably luscious revamp for the silver screen.

With rumours of a new adaption from the Chicago team, this classic tale looks set to endure for the next generation.

Frank Sinatra, Stubby Kaye, and Johnny Silver - "Guys And Dolls" from Guys And Dolls (1955)

Chicago (2002)

This vaudeville-style show has been making waves since its original Broadway run in 1975, and the 2002 film manages to capture the essence of the 70s production whilst bringing to life the swinging, corrupt, probation world of 1920s Chicago.

Renée Zellweger is exquisite as Roxie Hart, and Catherine Zeta-Jones revels in her roots as a musical theatre actress. In short: everyone brings their A-game to make this film an absolute riot from start to finish.

This scene won an oscar (We Both Reached for the Gun) | Chicago | CLIP

Oliver! (1968)

Another adaptation from the swinging 60s, Oliver! has all the charm and appeal of the original West End production, but with the added gloom and drama of Victorian London, bought to life on the big screen. Ron Moody is absolutely exceptional as Fagan, supported by an all-British cast who all help make this one of the best musical theatre films ever made.

Oliver! (1968) - I'd Do Anything Scene (6/10) | Movieclips

West Side Story (1961)

West Side Story caused a storm when it premiered on Broadway in 1957. It also marked the debut of future musical titan, Stephen Sondheim, who wrote the lyrics for Bernstein’s timeless score.

A modern revamp of Shakespeare’s Romeo and Juliet, brought to contemporary 50s New York, this film adaptation shows a grittier side to the fun and comedic Big Apple of Guys and Dolls. A stellar cast helps bring this to life on screen, with Natalie Wood captivating audiences with her portrayal of Maria, the love interest of Tony. Incredibly, Elvis Presley was approached for Tony, but his manager, Colonel Tom Parker turned down the part.

Irwin Kostal beefed up Bernstein’s orchestration for the film with a full-sized orchestra making the music even more impactful than Bernstein’s original.

West Side Story (4/10) Movie CLIP - America (1961) HD

Grease (1978)

Despite the haunting memories of having to awkwardly dance to ‘Summer Nights’ at your school disco, Grease is, for want of a better expression, an absolute banger.

It’s a testimony to how enduringly popular this film is that its songs continue to be played worldwide.

An iconic 1970s film set in the 50s, this film was set to be a classic as soon as it was made. John Travolta and Olivia Newton-John found the right chemistry to win over audiences’ hearts and minds.

Grease - Summer Nights HD

The Sound of Music (1965)

Arguably not just the greatest musical adaptation but the greatest film of all time, it’s impossible not to love this classic. Beautiful panoramic shots of the Austrian Alps enhance the drama of Richard Rodgers’ technicolour score, and Julie Andrews gives a career-defining performance. Christopher Plummer – who played Captain Von Trapp – was dismissive of the film’s success, never seeming to understand why it achieved such popularity until his grandchildren turned him around in the later years of his life.