It's all about the classical music composers and their works from the last 400 years and much more about music. Hier erfahren Sie alles über die klassischen Komponisten und ihre Meisterwerke der letzten vierhundert Jahre und vieles mehr über Klassische Musik.

Total Pageviews

Sunday, October 13, 2024

Saturday, October 12, 2024

Los Del Rio - Macarena (Bayside Boys Remix)

AFTER THE LOVE HAS GONE - Earth, Wind and Fire Lyrics

The Magical World of Musicals | The Lion King | The Greatest Showman

Friday, October 11, 2024

11 October: Frédéric Chopin’s Piano Concerto No. 1 Was Premiered

by Georg Predota

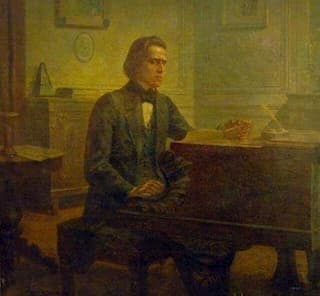

Frédéric Chopin, 1873

On 22 September 1830, Frédéric Chopin invited all of musical Warsaw to his home for a dress rehearsal of his E-minor Concerto. The rehearsal was enormously successful and a press review announced, “I hasten to bring a piece of good news to all friends of music and of native talent: Frédéric Chopin has completed his second grand piano Concerto. It is a work of genius, original, gracefully conceived with an abundance of imaginative ideas and perfect orchestration. The performance was masterfully executed… and we must add that Mr. Chopin will rob the Warsaw public of great pleasure if he departs without having publically produced this second Concerto.” Glowing accolades none withstanding, let us clear up some possible confusion. The referenced E-minor Concerto was the first of Chopin’s two piano concertos to be published, and it was subsequently given the opus number 11. It was composed immediately after the premiere of the F-minor concerto, which took place on 17 March 1830. This composition was published as his Piano Concerto No. 2 and given the opus number 21. As such, the E-minor concerto was composed and performed second but published first. The public premiere performance took place on 11 October 1830 at the Teatr Narodowy (National Theatre) in Warsaw, Poland, with the composer as the soloist.

Chopin playing piano © reddit

Chopin writes about his performance, “I was not the slightest bit nervous and I played as I play when I am alone. It went well. The hall was full. Goerner’s Symphony came first. Then My highness played the first allegro of the E minor Concerto, which I reeled off on a Streicher piano. The bravos were deafening… It seems to me that I have never been so much at ease when playing with an orchestra. The audience enjoyed my piano playing.” Rising political tensions prevented extended press reviews, and the local newspaper merely describes it as “one of the most sublime of all musical works,” but hardly the ecstatic tribute paid to the F-minor concerto earlier that year. Chopin performed the “Rondo” of the E-minor in Breslau 14 days later, and wrote to his family that the Germans had declared, “How light his touch as a pianist was.” However, Chopin complained, “that there was not a word written about the composition itself.” One local critic, however, “praised the novelty of the form, saying that he had never yet heard anything quite like it. “Perhaps” Chopin opined, “he understood better than any of them.” And a Munich performance in 1831 prompted the reviewer to write, “A lovely delicacy along with a beautiful and individualistic interpretation of the themes was characteristic of his cultivated style. On the whole, the work was brilliant and well written but without any particular originality or depth except for the main theme and middle second of the Rondo, which display a unique charm in their peculiar combination of melancholy and light-hearted passages.”

François-Joseph Fétis

Once the E-minor concerto had made its way to Paris, François-Joseph Fétis, one of the most influential music critics of the 19th century writes, “M. Chopin performed a concerto that caused as much astonishment as pleasure because of the novelty of its melodic ideas as well as its figuration, modulations, and form in general. His melodies are soulful, his keyboard writing imaginative, and originality prevails throughout. But mixed in with the qualities I have just identified are such weaknesses as over-rich modulations and a disordered succession of phrases, so that sometimes one had the impression of listening to an improvisation rather than composed music.” These early reviews decidedly colored the reception of the E-minor Concerto in the early twentieth century.

Frédéric Kalkbrenner, 1829

James Huneker dismissed it claiming “not Chopin at his very best,” and specifically writing on the E-minor he observed that “the first movement is too long, too much in one set of keys, and the working out section too much in the nature of a technical study.” And Donald Francis Tovey writes in the 1930’s that “the first movement of the E minor is built on a suicidal plan,” suggesting that it lacked “an essential element of harmonic contract and was therefore deficient from a structural point of view.” Critics initially might also have been guided by the dedication of the E-minor concerto to Frédéric Kalkbrenner, who was after all in the running to become Chopin’s teacher in Paris. However, today we understand that Chopin used virtuosity of differentiated intensity, inviting fluid interpretation and expression from his most technical writing. As has been observed, the E-minor concerto derives its “energy and momentum not from the contract of tonal centers, but from the contrast of lyric and virtuosic sections in the piano writing.”

Thursday, October 10, 2024

What YOUR favorite composer says about you!

Wednesday, October 9, 2024

Pink Floyd - Shine On You Crazy Diamond (Parts 1-5 & 7) [PULSE Restored ...

Last Words and Cause of Death of Famous Composers

Tuesday, October 8, 2024

A letter from Prague: the city in timeless harmony

Hattie Butterworth

Tuesday, October 8, 2024

Exploring the city’s cultural identity through architecture, history, and the legacy of Czech music

Prague is a city that architecturally is vaguely reminiscent of many places. I visited Prague for the first time earlier this summer, and found myself with memories of Italy, Germany and Scandinavia in my mind as I walked the cobbled streets. Then it has its political markers – the Lennon Wall with its ever-changing graffiti, marking global causes and the Memorial to the Victims of Communism active in Czechoslovakia between 1948 and 1989.

Its music – the distinctive Bohemian legacy of Dvořák, Suk, Smetana and others – perhaps gives the city an extra dimension to its colour. ‘My music is rhythmic because I am Czech,’ Bohuslav Martinů once said. ‘The national music of the Czechs is rhythm – strong and agile rhythm.’

But it was Bedřich Smetana (1824-1884), who was perhaps the first composer to revive the Czech musical language. A pioneer in his own right, he is now known in the country as the ‘father of Czech music’. This shift to writing in Czech came as later in life, he further embedded himself in Czech culture by learning to speak the language and the Czech nationalist movement caught wind. His own first language, as was usual among the middle classes in the Habsburg empire, was German.

Strong and lyrical, the Czech language has West-Slavic origins and is distinctly different to the German language of Smetana’s upbringing. Listening to the discussions of Czech audiences felt like a further journey into the music of the country. As I settled down in the National Theater for a production of Smetana’s late opera The Secret, the pastel and gold colours of the building glimmered and the strong, lyrical language reduced to whispers.

The interior of the National Theatre, Prague | Photo: National Theatre Prague

The interior of the National Theatre, Prague | Photo: National Theatre Prague

The Czech National Opera has commitment to celebrating its composer, Smetana, in his 200th anniversary year as part of the ‘Year of Czech Music’. The Secret lives alongside eight other Czech operas that Smetana wrote whilst principal conductor of Prague’s Provisional Theatre, the temporary home for Czech drama and opera before the National Theatre was built. Libuše (The Kiss) has also seen a new production this year, as well as revivals of The Bartered Bride and Dalibor.

Smetana’s operas blend the folk songs of his homeland with his personal style and have a poetic musical language. So too does his orchestral music, the most famous of which, his Má vlast was composed towards the end of his life and in the symphonic poem style pioneered by his friend Franz Liszt. Just as he began writing the work in 1874, Liszt lost the hearing in his left ear and a month later had also lost hearing in his right. He completed the work profoundly deaf.

By the end of 1874, Smetana resigned from his position as a conductor of the Provisional Theatre, because he couldn't hear well enough to keep doing his job. He wrote in his diary at the time: ‘If my disease is incurable, then I should prefer to be liberated from this life.’ He also suffered severely from tinnitus and wrote the ‘high E’ pitch he was hearing in the last movement of Bedřich Smetana's String Quartet No. 1, ‘From My Own Life’. In the middle of the finale, the quartet breaks off, followed by this mysterious high note. I wonder if this was a form of healing for Smetana, as embedding a tinnitus pitch into music has been known to significantly reduce the volume of the pitch. Was Smetana writing to sooth, rather than protest?

Many have argued about what caused the composer’s deafness and later his mental illness, leading for his body to be exhumed twice. In 1987 antibodies were found that pointed to syphilis, though the diagnosis still isn’t conclusive.

The Smetana Museum original manuscript of Smetana's opera The Kiss | Photo: Hattie Butterworth

The Smetana Museum original manuscript of Smetana's opera The Kiss | Photo: Hattie Butterworth

Learning of Smetana’s connections and tragedies came from the beautifully-curated Smetana museum, right on the Vltava river in a neo-renaissance building. It’s an intimate and moving experience, holding original letters and memorabilia from Smetana’s life. So too does the museum at Jabkenice, where a deaf Smetana composed many of his later works.

I often wonder about composers: does knowing about their lives matter or impact the way we hear the music? Perhaps the ins and outs of Smetana’s private life aren’t as important to the music as the knowledge is of his cultural journey throughout his life. When we listen to Smetana we are hearing a shift into a cultural identity and a start to the legacy we now know of the country’s music. It’s history through staves, scores and melodies.

The Czech Philharmonic closing the Prague Spring Festival 2024 | Photo: Hattie Butterworth

The Czech Philharmonic closing the Prague Spring Festival 2024 | Photo: Hattie Butterworth

Gramophone’s Orchestra of the Year 2024 was voted as being the Czech Philharmonic Orchestra. On my trip in June I saw the orchestra at the Rudolfinum concert hall in an all-Czech programme of music to close the annual Prague Spring Festival. From Smetana and Dvořák to the European premiere of Miroslav Srnka's Superorganisms, it was a unique opportunity to understand a full spectrum of Czech music and witness its effect on me. Perhaps the constant thread is the folk music of the country – still influencing Czech composers to this day and giving an intergenerational connection and community to the audiences.

In a recorded speech to receive the award, the orchestra’s chief conductor Semyon Bychkov said: ‘this orchestra lived by navigating through the highs and the lows, always attached to the national musical tradition, keen to preserve its unique sound and expression.’ Prague is engulfed with music. Walk around with your headphones in – Dvorak’s symphonies hold new resonance, bringing this iconic river and architecture to life through sound and history.

2024 is the Year of Czech Music. Find out more at visitczechia.com