by Georg Predota

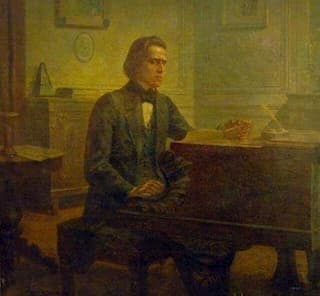

Frédéric Chopin, 1873

On 22 September 1830, Frédéric Chopin invited all of musical Warsaw to his home for a dress rehearsal of his E-minor Concerto. The rehearsal was enormously successful and a press review announced, “I hasten to bring a piece of good news to all friends of music and of native talent: Frédéric Chopin has completed his second grand piano Concerto. It is a work of genius, original, gracefully conceived with an abundance of imaginative ideas and perfect orchestration. The performance was masterfully executed… and we must add that Mr. Chopin will rob the Warsaw public of great pleasure if he departs without having publically produced this second Concerto.” Glowing accolades none withstanding, let us clear up some possible confusion. The referenced E-minor Concerto was the first of Chopin’s two piano concertos to be published, and it was subsequently given the opus number 11. It was composed immediately after the premiere of the F-minor concerto, which took place on 17 March 1830. This composition was published as his Piano Concerto No. 2 and given the opus number 21. As such, the E-minor concerto was composed and performed second but published first. The public premiere performance took place on 11 October 1830 at the Teatr Narodowy (National Theatre) in Warsaw, Poland, with the composer as the soloist.

Chopin playing piano © reddit

Chopin writes about his performance, “I was not the slightest bit nervous and I played as I play when I am alone. It went well. The hall was full. Goerner’s Symphony came first. Then My highness played the first allegro of the E minor Concerto, which I reeled off on a Streicher piano. The bravos were deafening… It seems to me that I have never been so much at ease when playing with an orchestra. The audience enjoyed my piano playing.” Rising political tensions prevented extended press reviews, and the local newspaper merely describes it as “one of the most sublime of all musical works,” but hardly the ecstatic tribute paid to the F-minor concerto earlier that year. Chopin performed the “Rondo” of the E-minor in Breslau 14 days later, and wrote to his family that the Germans had declared, “How light his touch as a pianist was.” However, Chopin complained, “that there was not a word written about the composition itself.” One local critic, however, “praised the novelty of the form, saying that he had never yet heard anything quite like it. “Perhaps” Chopin opined, “he understood better than any of them.” And a Munich performance in 1831 prompted the reviewer to write, “A lovely delicacy along with a beautiful and individualistic interpretation of the themes was characteristic of his cultivated style. On the whole, the work was brilliant and well written but without any particular originality or depth except for the main theme and middle second of the Rondo, which display a unique charm in their peculiar combination of melancholy and light-hearted passages.”

François-Joseph Fétis

Once the E-minor concerto had made its way to Paris, François-Joseph Fétis, one of the most influential music critics of the 19th century writes, “M. Chopin performed a concerto that caused as much astonishment as pleasure because of the novelty of its melodic ideas as well as its figuration, modulations, and form in general. His melodies are soulful, his keyboard writing imaginative, and originality prevails throughout. But mixed in with the qualities I have just identified are such weaknesses as over-rich modulations and a disordered succession of phrases, so that sometimes one had the impression of listening to an improvisation rather than composed music.” These early reviews decidedly colored the reception of the E-minor Concerto in the early twentieth century.

Frédéric Kalkbrenner, 1829

James Huneker dismissed it claiming “not Chopin at his very best,” and specifically writing on the E-minor he observed that “the first movement is too long, too much in one set of keys, and the working out section too much in the nature of a technical study.” And Donald Francis Tovey writes in the 1930’s that “the first movement of the E minor is built on a suicidal plan,” suggesting that it lacked “an essential element of harmonic contract and was therefore deficient from a structural point of view.” Critics initially might also have been guided by the dedication of the E-minor concerto to Frédéric Kalkbrenner, who was after all in the running to become Chopin’s teacher in Paris. However, today we understand that Chopin used virtuosity of differentiated intensity, inviting fluid interpretation and expression from his most technical writing. As has been observed, the E-minor concerto derives its “energy and momentum not from the contract of tonal centers, but from the contrast of lyric and virtuosic sections in the piano writing.”

No comments:

Post a Comment