Music is an important part of our life as it is a way of expressing our feelings as well as emotions. No matter where you are living on this globe. Some people consider music as a way to escape from the pain of life. It gives you relief and allows you to reduce stress. ... Music plays a more important role in our life than just being a source of entertainment.

Music affects our emotions. When we listen to sad songs, we tend to feel a decline in mood. When we listen to happy songs, we feel happier. Upbeat songs with energetic riffs and fast-paced rhythms (such as those we hear at sporting events) tend to make us excited and pumped up.

Music means the world to me. It makes me think about how it relates to life and I love the beats. Music is a way to express yourself, keep you company while you're alone, and always give you something to do. Music is a way of expressing me and being able to relate to other people.

It won't be a surprise to most that music can affect the human brain emotionally. ... Happy, upbeat music causes our brains to produce chemicals like dopamine and serotonin, which evokes feelings of joy, whereas calming music relaxes the mind and the body.

Music is a form of art; an expression of emotions through harmonic frequencies. ... Most music includes people singing with their voices or playing musical instruments, such as the piano, guitar, drums or violin. The word music comes from the Greek word (mousike), which means "(art) of the Muses.

Music is love. David Crosby sang this wonderful song already in 1971. "Everybody's sayin' music is love

Everybody'sayin' it's, you know it is..."

Music tells stories. Well, composers and musicians use music to tell stories. From all over the world. Music can be used to depict characters, places, actions and even emotions. Music is often used to heighten a mood, or to express a thought or feeling when mere words are not enough.

“[Music] can propel narrative swiftly forward, or slow it down. It often lifts mere dialogue into the realm of poetry. It is the communicating link between the screen and the audience, reaching out and enveloping all into one single experience.” The best stories engage all of the senses.

One of the great things about music in general, and in particular concert music, is that playing it opens up a whole new world of experience that further enhances the mind, physical coordination, and expression. Music lovers, who are also amateur performers, may choose to play in community ensembles (orchestra, band, choir), take lessons, perform with others, compose, and nearly anything else a professional musician may do, while maintaining their regular lives. All of this involves intense physical coordination in performing an instrument alone or with others, while reading musical notation, and adding delicate or strong nuanced changes to the music that only a performer can bring. In general, to an amateur musician, music can provide an escape from everyday life or an alternative means of expressing one's own capabilities. It is an important part of their lives and fills a need or an urge to create music.

I have been a music lover since my 4th birthday. Meanwhile, living as a German expat in the Philippines, I found out that Filipinos and Germans are music lovers. Among indigenous Filipinos, one important function of music is to celebrate or commemorate important events in the human life cycle. Fortunately, until today, these rich indigenous musical traditions live on. They serve as a reminder of the Filipinos' long history of musical talent and ingenuity.

Such is the case of Philippine music which today is regarded as a unique blending of two great musical traditions – the East and the West. ... The majority of Philippine Music revolves around cultural influences from the West, due primarily to the Spanish and American rule for over three centuries.

Becoming a German expatriate in the Philippines already 1999, I have attended many music events. I fell in love with Filipino classical music. So what does music really mean to Filipinos? It simply tells them where they've been and where they could go. It tells a story that everyone can appreciate and relate to, which is why it's a big part of every Filipino culture.

Music of the Philippines (Filipino: Himig ng Pilipinas) include musical performance arts in the Philippines or by Filipinos composed in various genres and styles. The compositions are often a mixture of different Asian, Spanish, Latin American, American, and indigenous influences.

Notable folk song composers include the National Artist for Music Lucio San Pedro, who composed the famous "Sa Ugoy ng Duyan" that recalls the loving touch of a mother to her child. Another composer, the National Artist for Music Antonino Buenaventura, is notable for notating folk songs and dances. Buenaventura composed the music for "Pandanggo sa Ilaw".

(To be continued!)

Musik ist ein wichtiger Teil unseres Lebens, da sie uns die Möglichkeit bietet, unsere Gefühle und Emotionen auszudrücken. Egal, wo wir auf der Welt leben. Manche Menschen betrachten Musik als eine Möglichkeit, dem Alltagsstress zu entfliehen. Sie verschafft uns Erleichterung und hilft uns, Stress abzubauen. … Musik spielt in unserem Leben eine wichtigere Rolle als nur Unterhaltung.

Musik beeinflusst unsere Emotionen. Wenn wir traurige Lieder hören, verspüren wir tendenziell eine gedrückte Stimmung. Wenn wir fröhliche Lieder hören, fühlen wir uns glücklicher. Fröhliche Lieder mit energetischen Riffs und schnellen Rhythmen (wie sie bei Sportveranstaltungen zu hören sind) machen uns aufgeregt und motiviert.

Musik bedeutet mir die Welt. Sie lässt mich darüber nachdenken, wie sie mit dem Leben zusammenhängt, und ich liebe die Beats. Musik ist eine Möglichkeit, sich auszudrücken, Gesellschaft zu leisten, wenn man allein ist, und immer etwas zu tun zu haben. Musik ist eine Möglichkeit, mich auszudrücken und mit anderen Menschen in Kontakt zu treten.

Es wird die meisten nicht überraschen, dass Musik das menschliche Gehirn emotional beeinflussen kann. ... Fröhliche, schwungvolle Musik regt unser Gehirn zur Produktion von Hormonen wie Dopamin und Serotonin an, die Freude auslösen, während beruhigende Musik Körper und Geist entspannt.

Musik ist eine Kunstform; ein Ausdruck von Emotionen durch harmonische Frequenzen. ... Bei Musik wird meist mitgesungen oder es wird ein Instrument wie Klavier, Gitarre, Schlagzeug oder Geige gespielt. Das Wort Musik stammt vom griechischen Wort (mousike), das „(Kunst) der Musen“ bedeutet.

Musik ist Liebe. David Crosby sang dieses wunderbare Lied bereits 1971: „Alle sagen, Musik ist Liebe, alle sagen, es ist Liebe, du weißt, es ist …“

Musik erzählt Geschichten. Komponisten und Musiker nutzen Musik, um Geschichten zu erzählen. Aus aller Welt. Musik kann verwendet werden, um Figuren, Orte, Handlungen und sogar Emotionen darzustellen. Musik wird oft eingesetzt, um eine Stimmung zu verstärken oder einen Gedanken oder ein Gefühl auszudrücken, wenn bloße Worte nicht ausreichen.

„[Musik] kann eine Erzählung schnell vorantreiben oder verlangsamen. Sie erhebt den bloßen Dialog oft in den Bereich der Poesie. Sie ist die kommunizierende Verbindung zwischen Leinwand und Publikum, die alles in ein einziges Erlebnis einbindet.“ Die besten Geschichten sprechen alle Sinne an.

Einer der schönsten Aspekte von Musik im Allgemeinen und von Konzertmusik im Besonderen ist, dass das Spielen eine völlig neue Erfahrungswelt eröffnet, die Geist, körperliche Koordination und Ausdrucksfähigkeit schult. Musikliebhaber, die auch Amateurmusiker sind, können in Ensembles (Orchester, Band, Chor) spielen, Unterricht nehmen, mit anderen auftreten, komponieren und fast alles tun, was ein professioneller Musiker tun kann, und das neben ihrem normalen Leben. All dies erfordert intensive körperliche Koordination beim Spielen eines Instruments allein oder mit anderen, beim Lesen von Noten und beim Hinzufügen feiner oder starker Nuancen zur Musik, die nur ein Musiker einbringen kann. Generell kann Musik für Amateurmusiker eine Flucht aus dem Alltag oder eine alternative Möglichkeit sein, die eigenen Fähigkeiten auszudrücken. Sie ist ein wichtiger Teil ihres Lebens und erfüllt ein Bedürfnis oder einen Drang, Musik zu machen.

Ich bin seit meinem vierten Geburtstag Musikliebhaber. Während meines Aufenthalts als deutscher Auswanderer auf den Philippinen habe ich herausgefunden, dass Filipinos und Deutsche Musikliebhaber sind. Unter den indigenen Filipinos ist eine wichtige Die Funktion der Musik besteht darin, wichtige Ereignisse im menschlichen Leben zu feiern oder zu gedenken. Glücklicherweise leben diese reichen indigenen Musiktraditionen bis heute fort. Sie erinnern an die lange Geschichte des musikalischen Talents und Einfallsreichtums der Filipinos.

So ist es auch mit der philippinischen Musik, die heute als einzigartige Verbindung zweier großer Musiktraditionen gilt – des Ostens und des Westens. ... Der Großteil der philippinischen Musik ist von kulturellen Einflüssen aus dem Westen geprägt, die vor allem auf die über drei Jahrhunderte währende spanische und amerikanische Herrschaft zurückzuführen sind.

Als ich 1999 als deutscher Auswanderer auf die Philippinen kam, besuchte ich viele Musikveranstaltungen. Ich verliebte mich in die klassische philippinische Musik. Was bedeutet Musik also wirklich für Filipinos? Sie erzählt ihnen einfach, wo sie waren und wohin sie gehen könnten. Sie erzählt eine Geschichte, die jeder schätzen und mit der sich jeder identifizieren kann, weshalb sie ein wichtiger Teil jeder philippinischen Kultur ist.

Musik der Philippinen (philippinisch: Himig ng Pilipinas) umfasst musikalische Darbietungskunst auf den Philippinen oder von Filipinos, die in verschiedenen Genres und Stile. Die Kompositionen sind oft eine Mischung verschiedener asiatischer, spanischer, lateinamerikanischer, amerikanischer und indigener Einflüsse.

Zu den namhaften Komponisten von Volksliedern gehört der Nationale Musikkünstler Lucio San Pedro, der das berühmte „Sa Ugoy ng Duyan“ komponierte, das an die liebevolle Berührung einer Mutter mit ihrem Kind erinnert. Ein weiterer Komponist, der Nationale Musikkünstler Antonino Buenaventura, ist bekannt für seine Notation von Volksliedern und Tänzen. Buenaventura komponierte die Musik für „Pandanggo sa Ilaw“.

(Fortsetzung folgt!)

%20(1).jpg)

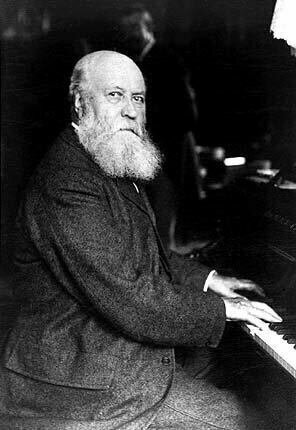

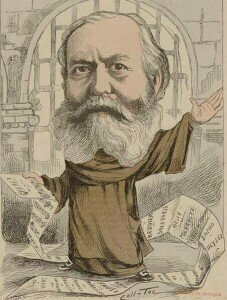

Charles Gounod was born 200 years ago, on 17 June 1818 in Paris. Today we primarily remember him as the composer of the opera Faust and an Ave Maria descant to the first prelude of J.S. Bach’s C-major prelude from the WTC. Yet, during the second half of the 19th century, he was one of the most respected and prolific composers in France. His musical influence on the course of French music was highly significant, but in the fractured post-Wagnerian critical climate towards the end of his life, his reputation took a severe hit. Son of a painter and engraver of considerable talent, Charles exhibited enormous talents in music and the fine arts. Pressured into studying law, Charles decided at age 16 to devote himself to music. Private lessons in counterpoint and harmony with Antoine Reicha prepared Charles for his enrollment at the Paris Conservatoire. Fully devoted to composition, Charles furthered his studies with Halévy and Le Sueur, and he won the Prix de Rome in 1839 with his cantata Fernand.

Charles Gounod was born 200 years ago, on 17 June 1818 in Paris. Today we primarily remember him as the composer of the opera Faust and an Ave Maria descant to the first prelude of J.S. Bach’s C-major prelude from the WTC. Yet, during the second half of the 19th century, he was one of the most respected and prolific composers in France. His musical influence on the course of French music was highly significant, but in the fractured post-Wagnerian critical climate towards the end of his life, his reputation took a severe hit. Son of a painter and engraver of considerable talent, Charles exhibited enormous talents in music and the fine arts. Pressured into studying law, Charles decided at age 16 to devote himself to music. Private lessons in counterpoint and harmony with Antoine Reicha prepared Charles for his enrollment at the Paris Conservatoire. Fully devoted to composition, Charles furthered his studies with Halévy and Le Sueur, and he won the Prix de Rome in 1839 with his cantata Fernand. The operatic stage in Rome—primarily populated by Donizetti, Bellini and Mercadante—was of little interest to Gounod. However, coming under the influence of the Dominican preacher Père Lacordaire, Gounod became genuinely fascinated by the music of Palestrina and the cultural legacy of Rome. He also crossed paths with Fanny Mendelssohn, and spent the remainder of his government stipend in Austria and Germany. After meeting with Felix Mendelssohn in Leipzig, Gounod returned to Paris and became music director of the Missions Etrangères church in 1843. He stayed in this position for the better part of four years until he formally enrolled at the seminary of St. Sulpice to begin studies for ordination into the priesthood. In the end, he rather abruptly abandoned his pursuit of the cloth and began to cast his eyes towards the glitzy world of opera.

The operatic stage in Rome—primarily populated by Donizetti, Bellini and Mercadante—was of little interest to Gounod. However, coming under the influence of the Dominican preacher Père Lacordaire, Gounod became genuinely fascinated by the music of Palestrina and the cultural legacy of Rome. He also crossed paths with Fanny Mendelssohn, and spent the remainder of his government stipend in Austria and Germany. After meeting with Felix Mendelssohn in Leipzig, Gounod returned to Paris and became music director of the Missions Etrangères church in 1843. He stayed in this position for the better part of four years until he formally enrolled at the seminary of St. Sulpice to begin studies for ordination into the priesthood. In the end, he rather abruptly abandoned his pursuit of the cloth and began to cast his eyes towards the glitzy world of opera. Gounod was not a household name on the Parisian musical scene, but all that changed when he started to orbit around the mezzo-soprano

Gounod was not a household name on the Parisian musical scene, but all that changed when he started to orbit around the mezzo-soprano  Music, according to Tinctoris, a Renaissance era theorist from the Netherlands, is a ‘nova ars’ – new art – which rejected all that had grown stale from the Middle Ages, and focused instead on infusing it with sweetness and truth (‘suavitas et veritas’). Thinkers and theorists such as Tinctoris joined Italian musicians, such as Gafori, to establish a systematic theory of composition.

Music, according to Tinctoris, a Renaissance era theorist from the Netherlands, is a ‘nova ars’ – new art – which rejected all that had grown stale from the Middle Ages, and focused instead on infusing it with sweetness and truth (‘suavitas et veritas’). Thinkers and theorists such as Tinctoris joined Italian musicians, such as Gafori, to establish a systematic theory of composition. One of the most significant achievements of the time in music and painting is the transition from successive to simultaneous composition. In painting, the classical triangle (just as the tonic triad in music) centers the image on canvas. Painting during the Renaissance era abandoned the medieval superposition of narrative scenes and arrived at the central perspective, at a definite element of form from a single point of sight to the unity of time, action and space. In Botticelli’s painting, the vanishing point is centered on the Holy Family contained in the classical triangle in the center of the painting, which is set into an Italian landscape. The clothing of the Magi and their retinue (Italian courtiers) is in the style of Renaissance Italy, which was intended to demonstrate unity of time, action and space, i.e. order, balance and harmony. The light within the painting is evenly distributed, leaving nothing in the dark, nothing ‘unseen’. Painting found its depth, so that viewers of these paintings could perceive the work almost as if they were looking through a window into three-dimensional space. Painters reinforced this perspective by framing their paintings with replicated window frames to further enhance and emphasize the ‘modern’ three-dimensionality of their work.

One of the most significant achievements of the time in music and painting is the transition from successive to simultaneous composition. In painting, the classical triangle (just as the tonic triad in music) centers the image on canvas. Painting during the Renaissance era abandoned the medieval superposition of narrative scenes and arrived at the central perspective, at a definite element of form from a single point of sight to the unity of time, action and space. In Botticelli’s painting, the vanishing point is centered on the Holy Family contained in the classical triangle in the center of the painting, which is set into an Italian landscape. The clothing of the Magi and their retinue (Italian courtiers) is in the style of Renaissance Italy, which was intended to demonstrate unity of time, action and space, i.e. order, balance and harmony. The light within the painting is evenly distributed, leaving nothing in the dark, nothing ‘unseen’. Painting found its depth, so that viewers of these paintings could perceive the work almost as if they were looking through a window into three-dimensional space. Painters reinforced this perspective by framing their paintings with replicated window frames to further enhance and emphasize the ‘modern’ three-dimensionality of their work.