In the sentimental tradition still perpetuated in CD notes, Mozart composed his last three symphonies in the summer of 1788 from inner compulsion, with no prospect of performance. Alfred Einstein, in his widely read biography, writes of Mozart’s ‘appeal to eternity’. This is poppycock. Mozart never wrote without external stimuli. He almost certainly intended the symphonies, Nos 39‑41, for subscription concerts he was planning in Vienna. A recently discovered document also reveals that No 40 was performed in a concert series organised by Baron Gottfried van Swieten. It was apparently so poorly played that Mozart left the room before the end. Beyond this, the three symphonies would have come in useful on Mozart’s German tours in 1789 and 1790, and for a long-planned visit to London.

Podcast – Exploring Mozart: A special edition of the Gramophone Podcast sees Editor Martin Cullingford talk to Richard Wigmore about Mozart's extraordinary life and music.

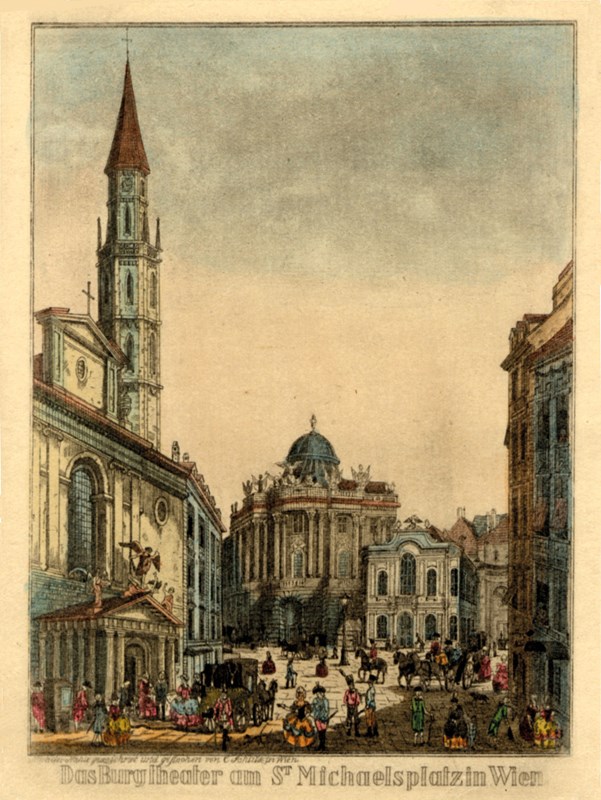

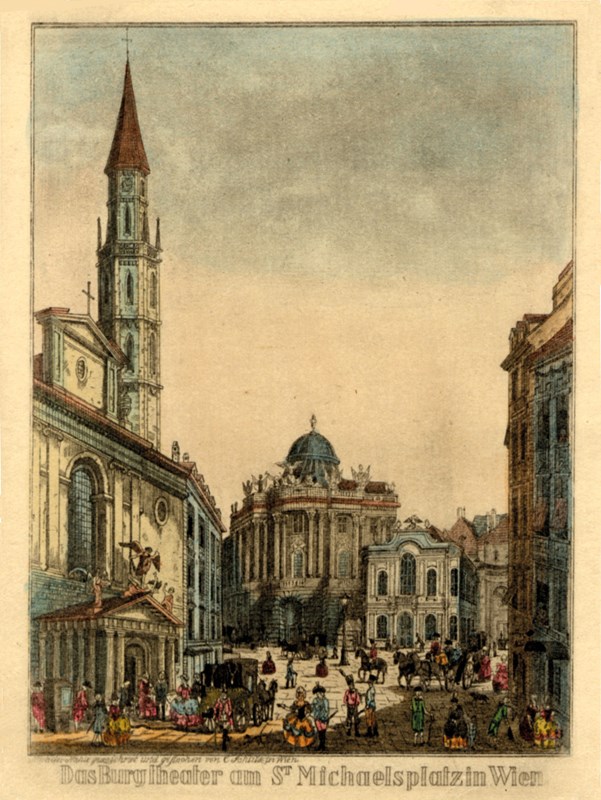

While it is a romanticising fallacy to view Nos 39, 40 and 41 as Mozart’s symphonic testament, the contrasts between them do suggest that he designed them to display the fullest range of his art. Like most minor-key symphonies of the day, the melancholy and turbulent No 40 in G minor omits trumpets and drums. Mozart originally scored it for a typical chamber orchestra of flute, oboes, bassoons, horns and strings. Soon afterwards – perhaps for the performance at van Swieten’s – he enriched the orchestration with clarinets, drastically modifying the oboe parts in the process. In its revised version the symphony was probably performed in a charity concert at Vienna’s Burgtheater in April 1791, conducted by Mozart’s supposed antagonist Salieri.

The Burgtheater in Vienna (Bridgeman Images)

Christian Schubart, the poet of his near-namesake’s song ‘Die Forelle’, characterised G minor as the key of ‘discontent, unease, gritting of teeth in anger’. Add in Mozart’s harmonic audacity and lyrical pathos and you have a fair summary of the symphony’s outer movements. The finale rises to a pitch of anguish barely matched in Mozart’s output. How ironic, then, that Robert Schumann, at a time when Mozart was either patronised or idealised as an emblem of a lost Eden, admired the G minor merely for its ‘buoyant Hellenic charm’!

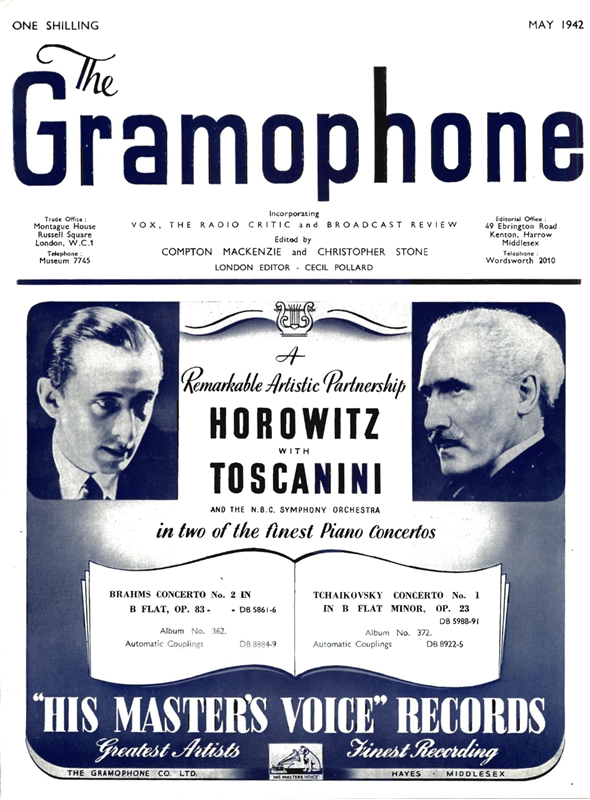

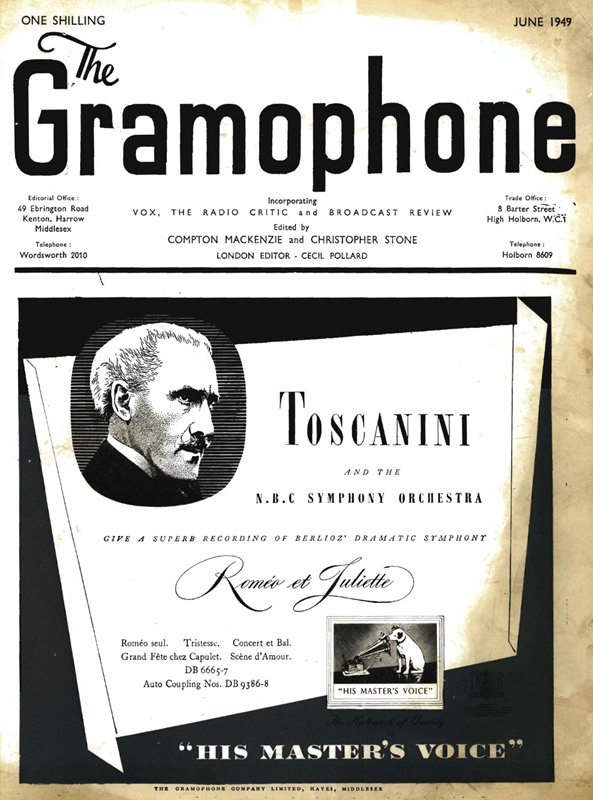

In 1915 No 40 became Mozart’s first symphony to be recorded, courtesy of the Victor Concert Orchestra. (You can check it out on YouTube. Once is enough.) A handful of recordings followed between the wars, since when a trickle has become a torrent. By now dreaming in G minor, I’ve listened to some 50 versions, on CD and streamed. But to avoid an annotated shopping list, I’ve self-denyingly limited my survey to just 20 versions. Apologies to readers whose favourite recordings have no place here. My aim is not to showcase the 20 ‘best’ (whatever that means) but to embrace a wide interpretative range across nine decades.

LEGENDARY MAESTROS

First, a handful of conductors born in the 19th century, with all that implies. In Germany, Hermann Abert’s revolutionary biography of 1923‑24 had portrayed a demonically driven, ultimately tragic Mozart. In Britain that notion only gained currency much later. The two most influential advocates of Mozart between the wars were the composer-musicologist Donald Tovey, for whom the composer’s exquisite formal perfection precluded tragedy, and Thomas Beecham, whose 1937 recording with the London Philharmonic Orchestra is preserved in remarkably good sound.

Surprisingly for a musical sensualist, Beecham chooses the original version, minus clarinets. Tempos, except in the finale, are leisurely, with long sostenuto lines and liberal use of portamento – slides between notes. The Andante unfolds at a ponderous six beats to the bar, while the doggedly accented Minuet is redeemed only by the nostalgic delicacy of the Trio. Without plumbing extremes of anguish, the first movement combines strong yet pliant rhythms with a con amore treatment of the sighing second theme. The finale, shorn of its repeat, is taut and unflinching. The Dutton transfer (9/97 – nla) allows plenty of crucial wind detail in the tuttis.

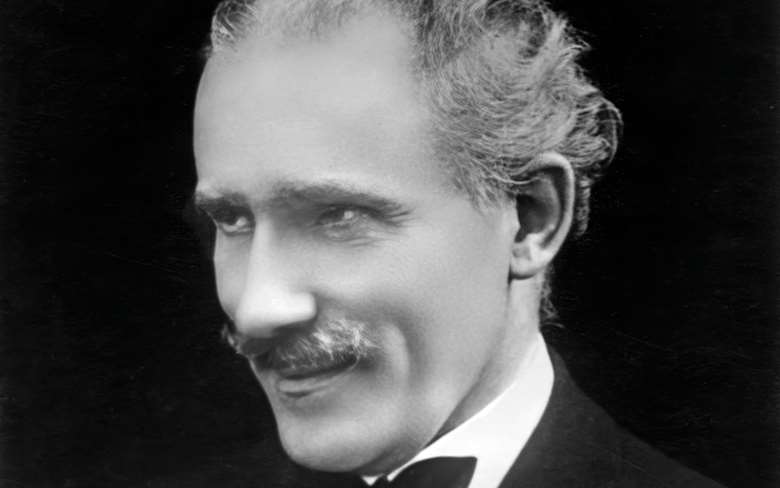

Either side of the Second World War, the two maestros who were often pitted against each other make for an intriguing, unpredictable comparison. With the NBC Symphony Orchestra in 1938‑39, the ‘back-to-the-score’ anti-Romantic Arturo Toscanini, using the clarinet version, moulds the first movement as flexibly as any conductor. The opening violin theme, with its added swells and ebbs, and the lingering leadback from the development to the recapitulation sum up the Toscanini approach. The groundswell of divided violas is barely audible.

In contrast, the subjective visionary Wilhelm Furtwängler, opting for the original version with the Vienna Philharmonic in 1948‑49, conceives the first movement in a single tragic span. The opening theme is starkly unbeautified, devoid of any hint of accent or crescendo. Beginning at a flowing andante – two rather than six beats to the bar – and making liberal and expressive use of portamento, Toscanini’s second movement is likewise freer in tempo than Furtwängler’s. Like Beecham, Furtwängler views the movement as an adagio; yet more than Beecham, who tends to glory in the moment, he vindicates his slowness with a burdened, far-seeing intensity of line. Mozart’s remote modulations become mystically charged. The old gold of the Viennese horns glows seductively in the Trio, while the finale, transcending some scrambled string-playing, combines an almost unhinged violence with the subtlest easing of the pulse for the second theme. Toscanini, by contrast, slams on the brakes here.

If Furtwängler presents the G minor Symphony as the creation of a demonically inspired Mozart, Bruno Walter, with the Columbia Symphony Orchestra, conducts the most elegiac performance on disc. You’d never guess from Walter’s backward-leaning performance that Mozart marked the first movement Allegro molto, with a time signature of two beats to the bar. ‘Sing, gentlemen, sing’ was the conductor’s plea in a famous 1956 rehearsal of the Linz Symphony. He is true to his word here, seizing every opportunity for pathos. The Andante, ravishing as sheer sound, is weighed down by loving ritardandos. Walter does display a fine control of tension in the developments of the outer movements. But the final impression is of a weary fatalism, epitomised by the minor-key returns of the second themes and the woodwind’s lingering envoi in the Minuet.

Cooler and more ‘objective’, Walter’s contemporary Otto Klemperer directs the Philharmonia in a typically rugged, plain-speaking performance, one that sets a premium on clarity of texture. But with a leaden Andante and the steadiest finale on disc, the upshot is marmoreal. Klemperer does, though, score over most conductors before the 1990s by dividing the violins left and right, so that Mozart’s antiphonal writing – say in the truculent counterpoint of the first movement’s recapitulation – makes its due effect.

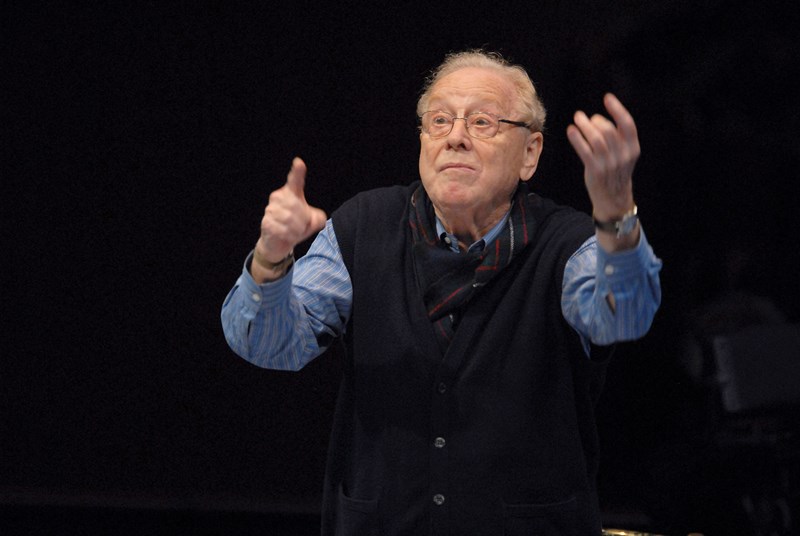

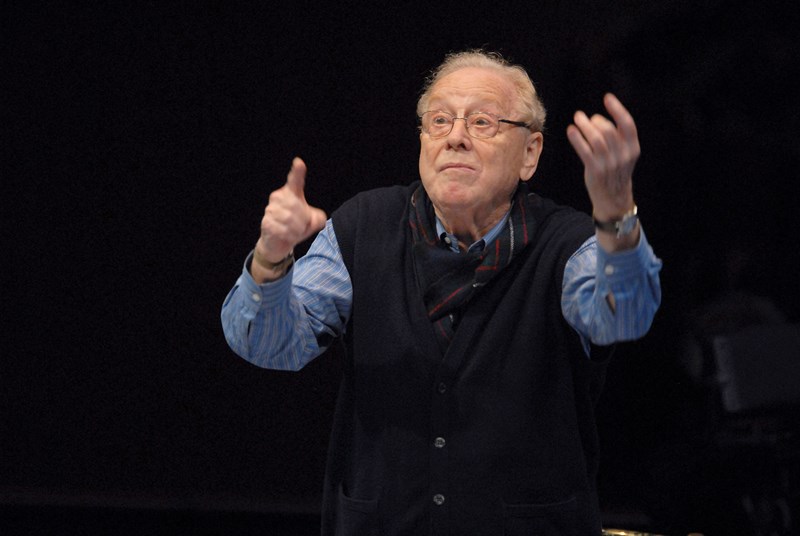

SLIMMED FORCES

All the pre-1960 performances use a string band based on a minimum of 12 first violins. From the mid-1960s, recordings of the G minor Symphony with around 35 players began to appear alongside more traditional performances. Of the latter, Karl Böhm, Herbert von Karajan and Colin Davis have their takers. More compelling, for me, is Leonard Bernstein’s live 1984 recording with the Vienna Philharmonic. With Bernstein the dividing line between illumination and indulgence can be a thin one. On the whole he locates it here. The VPO strings play with lightness and point, and those so-distinctive Viennese horns cut through thrillingly. Despite the low-voltage opening, Bernstein vindicates his leisurely tempos for the first two movements with the burning intensity of his phrasing. The finale, ominously glinting horns to the fore, is incandescent.

One of the earliest recordings with scaled-down forces, from Daniel Barenboim and the English Chamber Orchestra, still stands up well. The ECO always played superbly for EMI’s new star conductor, whose reverence for Furtwängler is unmissable. Like the German maestro, he chooses the original version minus the softening clarinets; and his tempos, often his phrasing, are virtually identical. The outer movements are as uncompromising as Furtwängler’s, with an added clarity and precision. More than in any earlier recording, you’re aware of Mozart’s novel, democratic treatment of the wind: say, in their cussed altercations with the strings towards the end of the first-movement development, or their wailing dissonances in the recapitulation’s contrapuntal imbroglio.

Benjamin Britten: chamber-musical delicacy with the ECO (Getty Images)

‘Grace plus dissonant fierceness’ was my jotted summary of the performance Benjamin Britten recorded with the same orchestra in the ideal acoustic of the Snape Maltings. Like most conductors from now on, Britten uses the version with clarinets, first among equals in the ECO’s superlative wind section. The first movement, half a notch slower than Barenboim’s, marries fire and subtle flexibility of pulse. No other conductor probes the symphony’s harmonic darkness so unerringly. The individual character of the wind players shines in the Andante, a musing conversation broken by tutti outbursts of shocking ferocity. Britten was the first conductor on disc to observe both of Mozart’s repeats in the Andante and finale, finding new nuances and phrasings the second time round. Clocking in at 16 minutes, the Andante emerges more than twice as long as the first movement. Britten justifies the proportions. The Minuet is brusque and bristling, with disruptive explosions on held high notes: illicit, perhaps, but all of a piece with Britten’s conception.

While Britten is no slouch, Yehudi Menuhin, with the Sinfonia Varsovia, is faster and leaner in each movement. By 1989 the period-instrument movement was in full spate. Menuhin’s determinedly anti-Romantic conception, gamely executed by the Polish band, taps into the spirit of the age. In the first-movement development, impetuosity can threaten rhythmic poise. But each movement, including a naturally flowing Andante (where Menuhin reveals himself master of the lyrical line) and a muscular, one-in-a-bar Minuet, has an urgent, inevitable sweep.

Two more recent recordings combine a Romantic impulse with period-performance practice: a marriage of convenience that more often than not works. With a slimmed-down (or so it sounds) Berlin Philharmonic, playing with light bow strokes and minimal vibrato, Simon Rattle chooses consistently swift tempos. Until the violent central outburst, the Andante is an airborne dance with an underlying minuet lilt, while the Minuet proper becomes a no-holds-barred scherzo, divided violins locked in combat. Textures are ideally transparent throughout. Rattle’s Romantic instincts are evident in, say, the wistful slowing into the first movement’s recapitulation and the all-passion-spent treatment of the second subject. The recasting of the finale’s lyrical second theme in G minor becomes a nostalgic envoi, à la Bruno Walter.

Taking all possible repeats – including both in the Andante – John Nelson directs the Ensemble Orchestral de Paris in another eager, up-tempo performance, less driven in the Minuet and disinclined to linger in the Allegros’ pools of lyricism. The Gallic horns are a tangy presence in the pastoral Trio. Nelson is unflinching in Mozart’s fierce contrapuntal developments, enhanced by keening wind. A pity that he fails to divide his violins left and right, as Mozart’s writing demands.

ENTER THE PERIOD BRIGADE

After early sallies from Christopher Hogwood et al, by the 1990s performances on period instruments (gut strings, valveless horns, woodwind with an agreeable ‘edge’) had become the norm. Roger Norrington, conducting the London Classical Players, starts as he means to go on, with a fast, tense Molto allegro underpinned by agitatissimo divided violas. From the wailing oboes and bassoons on the theme’s repeat, Norrington seizes every opportunity to stress the dissonant potential of the unblended period woodwind. The conductor has his own ideas on articulation and accentuation; and at his blithe tempo the little ‘flicking’ figures that pepper the Andante become charmingly decorative – a preview here of the airy trio for the Three Boys in Act 2 of Die Zauberflöte.

Released at the same time as Norrington’s version (despite having been recorded two years earlier), John Eliot Gardiner directs an equally fiery but more ‘central’ performance founded on a larger (or so it sounds) body of strings. Both conductors generate a fine fury in the developments of the two Allegros, propelled by splenetic divided violins. I love the way Gardiner encourages the horns to let rip in the first movement’s recapitulation. Differences between the two conductors are sharpest in the middle movements. At 13'53" to Norrington’s 12'08" (including both repeats), Gardiner’s Andante has breadth and gravitas. Similarly, while Norrington’s third movement, foreshadowing Rattle’s, becomes an incontinent scherzo, Gardiner’s exudes a defiant toughness. There’s room for both.

Trevor Pinnock, with The English Concert, is hardly less fiery in the outer movements but allows more room for lyrical grace. This is a natural, unaffected performance, combining light, precise articulation with a care for the singing line and inner detail. There are no quirks, no exaggerations. Phrases always breathe. The Andante, shaped with gentle flexibility, and the Trio have a chamber-musical intimacy, with the players listening intently and responding to each other.

Like Norrington’s, Pinnock’s ensemble numbers around 35. We know that Mozart relished larger forces when he could get them. So we can guess he would have approved of Marc Minkowski’s band, based on 12, rather than eight, first violins. More than the three fine British period performances, Minkowski tends to go for extremes, whether in the ultra-fragile pianissimos in the Andante (rather touching) or the contrast between the frenetic Minuet-scherzo and the slower, lovingly phrased Trio. The symphony opens with subdued tension at the fastest possible tempo; after an added pause Minkowski slows for the second theme, then tears into the development. It’s exciting, but can become a bit of a scramble.

From the barely controlled impetuosity of the opening, René Jacobs’s performance with the superlative Freiburg Baroque Orchestra likewise mines extremes of ferocity and delicacy. He goes further than Minkowski in his tempo tweaks, whether lingering at the opening of the first movement’s development or drifting into reverie before the return of the Andante’s main theme. Jacobs observes all possible repeats, and, crucially, uses them to further the symphonic drama. His idiosyncrasies can illuminate or (say, in the sudden unprovoked forte on the repeat of the Trio) irritate, according to taste. But there is no hint of routine. If you want a demonstration that Mozart’s instrumental music is opera by other means, here it is.

Like Pinnock, Frans Brüggen, 2010 vintage, combines expressive phrasing with minimal flexing of the pulse. While not quite immaculate, the playing of his Orchestra of the Eighteenth Century is always alive, full of individual nuances and colours. The flute-led woodwind scream out against the rebarbative string counterpoint in the finale’s development – a thrilling moment. Mystifyingly, though, Brüggen ditches both repeats here and in the easily paced Andante.

A smaller-scale Dutch period performance, from Jos van Immerseel’s Anima Eterna in 2001 (Zig-Zag/Alpha, 9/04), is the fastest and straightest of all, sticking sedulously to the letter of the score. Stravinsky, you suspect, would have approved. In extreme contrast are Riccardo Minasi and Ensemble Resonanz. Cultivating a notably abrasive sound world, Minasi eclipses even Jacobs in wilful subjectivity. He vindicates his manic tempo in the finale. But the first movement, replete with added dynamics, veers between febrile activity and exhaustion, while the Andante has barely four bars in the same tempo.

‘Hungry’ was my instant reaction to the opening movement from Nikolaus Harnconcourt, in his second recording with the Concentus Musicus Wien. Familiar Harnoncourtisms – tempo distensions, added pauses – abound. Speed choices are provocative. The Andante, quicker even than Norrington’s, opens as an ethereal dance, then generates an unmatched vehemence in the central development. Ricocheting antiphonal violins spit venom in the Minuet, taken at the breakneck speed suggested by Czerny’s metronome marking, while the Trio brings out the closet Romantic in Harnoncourt. In the finale, the conductor takes a surprisingly moderate view of the Allegro assai, caressing the second theme, then building inexorably through the development. The pungent timbres of the wind, raucous horns to the fore, are gloriously present. For all its hesitations and rhetorical emphases – emulated in varying degrees by later period practitioners – Harnoncourt’s performance is unsurpassed for colour and cumulative intensity.

THE FINAL CULL

Among period recordings, Pinnock, Gardiner, Norrington and the more subjective Jacobs and Harnoncourt all have strong claims. For inspired intuition, Britten and Furtwängler are in a class of their own. Yet forced to nominate a top library choice for the G minor Symphony, as the rules dictate, I’d plump for Charles Mackerras and the fabulous Scottish Chamber Orchestra: modern instruments (except for valveless horns) played with a discriminating awareness of period practice, and recorded in the clear yet glowing acoustic of Glasgow’s City Halls.

Mackerras with the Scottish CO: expressive phrasing, transparent textures and urgent tempos (Chris Christodoulou/Bridgeman Images)

Mackerras’s tempos – quick yet never hectic – seem spot on, his rhythms, founded on a superbly articulate bass line, taut and vital. The first movement marries urgency and lyrical eloquence, while in the flowing Andante the conductor is specially alive to the moments of harmonic mystery and the conversations within the inner voices. The finale ideally balances ferocity and pathos, with just a hint of sorrowful lingering when the minor key returns before the close.

The G minor Symphony was doubtless one of the works the early 19th-century critic Friedrich Rochlitz had in mind when he wrote that Mozart’s ‘modulations are frequently bizarre, his transitions rough … rarely is he delicate without emitting tense, painful sighs’. This is a verdict that would have astonished earlier generations, though evidently not Furtwängler. Locating the symphony’s dark, disturbing heart, the finest modern interpreters, Harnoncourt and Mackerras among them, would surely concur.

This article originally appeared in the February 2022 issue of Gramophone magazine. Never miss an issue – subscribe today