By Gaby Reucher

The pandemic prompted many German classical music festivals and orchestras to adopt more sustainable practices.

How COVID-19 made Germany’s classical music industry more sustainable

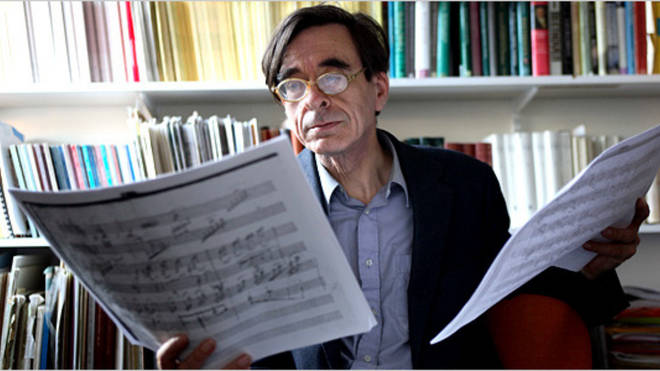

The coronavirus pandemic has had a major impact on the classical music industry in Germany, and around the world — yet there are lessons to be learned from the crisis. At least that's how Christian Höppner, Secretary General of the German Music Council, sees it: "We should now view the pandemic period as an opportunity and make cultural life fit for the future; from the point of view of sustainability, as well." It's not just about protecting nature and the environment, but also about sustainably promoting young musicians, he added.

The financial aid provided by Germany during the pandemic has been exemplary, according to Höppner. Nevertheless, many musicians have given up their profession and sought more crisis-proof work. Some prospective students who had passed notoriously difficult entrance exam even chose not to start studying music. "That would have been unthinkable before COVID-19. Then, passing an entrance exam was like winning the lottery. There has since been a very strong reorientation," says Höppner in an interview with DW.

Christian Höppner in a blue suit with a red bow tie and glasses.

Christian Höppner of the German Music Council says the pandemic has provided an opportunity for change

Sustainability from the office to the orchestra

A number of German festivals and orchestras are leading the way when it comes to how they treat both the environment and their artists. The entire staff of the Dresden Music Festival, for example, is participating in the city's "Culture for Future" pilot project on sustainability in cultural enterprises. "It starts with our attitude. We have to keep sustainability in mind in every planning process," explains artistic director Jan Vogler in an interview with DW. This is done in the office, in marketing initiatives and even in concert design.

More tickets are being sent out digitally, as are newsletters, brochures, program booklets and the festival magazine. The buffets for the artists feature regional cuisine, and glass bottles are used instead of plastic ones. The festival also relies on electric vehicles to transport artists and their instruments. It's still early in the process, says Vogler, but the team is enthusiastic about the new green steps.

A reduced carbon footprint

When air traffic came to a near global standstill in 2020 due to the coronavirus pandemic, orchestras were forced to cancel their tours. The question arose as to whether ensembles actually needed to do so much jet-setting.

Naturally, following the loosening of coronavirus restrictions, many people are longing to hear live music again, says Höppner. "But no one can avoid asking themselves how sustainable what we're actually doing is anymore" he adds.

The fact that the music touring industry needed a reboot was apparent before the pandemic, says Steven Walter, artistic director of the Beethovenfest Bonn. He would like to move away from having large orchestras go on tour and also have musicians travel less and instead spend more time at a destination — for example staying at a festival for one or two weeks and leaving their mark. "For us, this is also interesting artistically — to develop specific projects and ideas for a unique profile for the festival," says Walter.

Compensating for CO2 emissions

Yet avoiding air travel isn't always possible for the Dresden Festival or the Rheingau Music Festival, which aim to bring international artists to audiences around the world. Nevertheless, it is possible to make artists' travel more sustainable, says Dresden Music Festival artistic director Jan Vogler. "We try to take advantage of Dresden's location: Berlin, Prague and even Vienna are nearby," he adds.

Orchestras are also scheduling tours so that distances between venues are as short as possible. Recently, the Berlin Philharmonic toured Austria, Slovenia and Croatia, taking a bus between destinations. "In fact, artists also prefer this," says Vogler, "Before, they were often sent zigzagging nonsensically around the world. As long as it was feasible, no one thought about the fact that it was often an ordeal for them to manage these travel routes and the concerts."

A forest for Bach

Offsetting CO2 emissions is one way of compensating for distances driven and flown. The money goes to environmental protection projects. This allowed the Deutsche Kammerphilharmonie Bremen to be certified as climate neutral in 2020, even before the pandemic. Now, the ensemble only travels by train within Germany.

The Leipzig Bach Festival, which prior to the pandemic attracted a large international audience of 73,000 visitors to Leipzig, has also made environmental commitments. Director Michael Maul is raising funds to support the "Forest for Saxony" project and to have a "Johann Sebastian Bach Forest" planted near a former lignite mining area.

Music streaming as a solution?

Streaming and videoconferencing have been a major part of the current digital transformation, which was accelerated by the pandemic. Many industries, including the music industry, turned to streaming. Together with the Thuringia Bach Festival and the Köthener Bach Festival, the Leipzig Bach Festival founded their own platform last year to present selected concert streams that will continue after the coronavirus pandemic.

In the longer term, however, streaming, with its high energy consumption, is not all that sustainable either. Jan Vogler of the Dresden festival tries to combine meetings with concerts. "It's almost no longer conceivable for me to leave directly after a London or Paris concert. I usually stay an extra day and meet the partners we work with there."

COVID-19 restrictions in the arts industry inevitably raised the question: What is the value of culture?

"Is the music business dominated by a few big stars who make millions from it, or is culture really the daily bread one needs to live?" If the latter is true, then musical life has all the more reason to be underpinned by sustainable structures, says Christian Höppner. This is also done in relation to educating musicians.

Currently, music lessons are often substituted for short-term projects done at many schools, and funding for up-and-coming artists also tends to flow into temporary projects that are not sustainable. The pandemic, however, has shown how quickly young talent is lost.

"As an organizer, you have a responsibility in terms of human resources to protect the artists," says Beethovenfest Bonn director Steven Walter. This also applies to dealing with talent. "You can't burn them out and then drop them. It's about investing in their careers in a sustainable way, even when things aren't going so well at the moment."

This article was originally written in German.