It's all about the classical music composers and their works from the last 400 years and much more about music. Hier erfahren Sie alles über die klassischen Komponisten und ihre Meisterwerke der letzten vierhundert Jahre und vieles mehr über Klassische Musik.

Total Pageviews

Sunday, October 27, 2024

Who Wants To Live Forever | Arena di Verona 2024 ❤

Saturday, October 26, 2024

This is Why Beethoven's Symphony No.5 Is So Incredibly Popular

Friday, October 25, 2024

Composers of the Zodiac: Tropic of Scorpio

by Georg Predota, Interlude

Constellation of Scorpio

The constellation of Scorpio is associated with a number of myths. In one version rooted in Greek mythology, the legendary hunter Orion boasted to the goddess Artemis that he would kill every animal on Earth. Insulted by Orion’s excessive pride, Artemis sent a scorpion to kill Orion. Their heroic battle caught the attention of Zeus, who raised both combatants to the sky to serve as a stern reminder for mortals.

“Scorpio”, plate 23 in Urania’s Mirror

by Jehoshaphat Aspin

To this day, when Scorpio rules the night sky—from about October 23 to November 21—Orion goes away. It has been said the Scorpio is one of the most misunderstood signs of the zodiac. Because of its incredible passion and power, Scorpio is often mistaken for a fire sign. In fact, Scorpio is a water sign that derives its strength from the psychic and emotional realm. Extremely clairvoyant and intuitive, individuals born under the sign of Scorpio are imaginative and intense. They are ruled by Pluto (god of the Underworld) and Mars (god of War), and always know what they want and how to get it. Composer and pianist Roderick Elms, who for many years was the London pianist to cellist Mstislav Rostropovich as well as organist to the London Symphony Orchestra, provides his musical take on this powerful astrological sign.

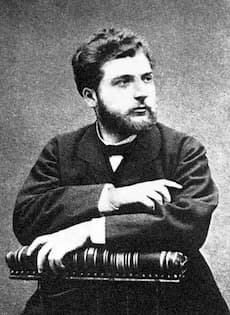

Georges Bizet

Georges Bizet

Born on 25 October, Georges Bizet was a brilliant student at the Conservatoire de Paris, winning a great number of prizes including the prestigious Prix de Rome in 1857. Once he had returned to Paris after almost 3 years in Italy, he quickly found out that his music was not in demand. In the true spirit of a Scorpio, Bizet was nevertheless determined to orchestrate a career in music. His intentions weren’t necessarily nefarious, he simply knew what he wanted and wasn’t afraid to work hard to realize his ambitions. He was greatly optimistic about the premiere performance of his opera Carmen on 3 March 1875. In the event, it turned into a veritable disaster. The opera was on the verge of being withdrawn, and it has been suggested that the theater had to give away free tickets in order to boost attendance. Bizet, unfortunately died a mere three months after the premiere, and it is suspected that the negative reception contributed to his fatal heart attack. As a biographer wrote, “The spectacle of great works unwritten either because Bizet had other distractions… or because of his premature death, is infinitely dispiriting, yet the brilliance and the individuality of his best music is unmistakable.”

Aaron Copland

Aaron Copland

Born on 14 November, Aaron Copland had a gift for natural leadership, and a great talent for management in all walks of life. On the outside, he displayed a deep calm while his true feelings were hidden deep within. Sensitive to the feelings of others, he displayed the greatest tact in all social interactions. Copland had a thorough understanding of the material world, and he clearly knew that his power and influence must be used for the benefit of mankind. And like a true Scorpio, he had the ability to inspire people and direct them to become part of his vision. Copland was a meticulous and hard worker, but he was easy going in almost all social situations. Realism was part of his nature as he dressed simply, yet he remained mysterious and sensitive. Copland easily bounced back from professional and personal failures, and true to his zodiac, he was wisely assertive throughout his life and in his music.

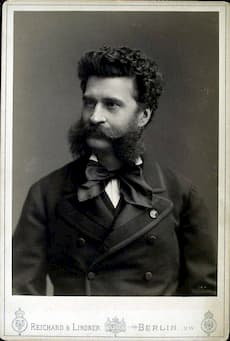

Johann Strauss

Johann Strauss II

Seductive and beguiling, Scorpio is the sign most closely associated with sex. Sex isn’t solely about pleasure for the sensual scorpions, as they also crave the physical closeness, spiritual illumination, and the emotional intimacy that sex can provide. Well, Johann Strauss II, born on 25 October, certainly wasn’t shy when it came to sexual adventures. Like any good son, he initially tried to outdo his father in all aspect of life, particularly in music and sexual promiscuity. He mesmerized Viennese audiences, and in a blatant repeat of history, Vienna’s female population would swoon at the mere mention of his name. His popularity with the ladies got him into serious trouble, as on more than one occasion, jealous husbands challenged him to duels, and once he even had to seek refuge in the Austrian Embassy, barely escaping a double-barrel shotgun gently inviting him to marry a young Russian maid. When a planned marriage did not materialize, Strauss bedded dozens of eager groupies. Strauss II eventually did marry the mistress to a high-profile banker, but following her death, he frequented the local bordellos and after seven weeks he was married again. Be that as it may, music and sex definitely ruled the life of this Scorpio.

Niccolò Paganini

Niccolò Paganini

Born in Genoa on 27 October, Niccolò Paganini left an irrefutable mark on the history of instrumental music and 19th century social life. He was a born leader with extra-ordinary drive and determination. Once he made up his mind to study the violin and discover new and hitherto unsuspected effects that would astound people, nothing would stand in his way. He became obsessed with fame and money, and his relentless ambition translated into increasingly bizarre behavior. Supposedly, he was once invited to play at a funeral, but interrupted the ceremony with a twenty-minute solo concerto. And I am sure you’ve heard the story of him spending eight days in jail for drugging his girlfriend and forcing the abortion of his child. There was even a rumor that he had murdered a woman, used her intestines as violin strings and imprisoned her soul within the instrument. Women’s screams were supposedly heard from his violin when he performed on stage. Always concerned about appearances and to project success and self-satisfaction, this Scorpio demanded unconditional respect and attention.

Five of the Most Famous Women Composers of the Classical Era

Most historians agree that the Classical Era began in the 1750s and didn’t give way to the Romantic Era until the 1820s or 1830s.

Obviously this was a time when professional opportunities for women were limited compared to the present day, but it was also a time when new ideas about what women could learn and accomplish had begun to take root.

There are many women who wrote great music during the Classical Era. Here are five of the most famous.

Marianna Martines (1744-1812)

Marianna Martines was born in 1744 in Vienna, Austria.

Importantly for Martines’s career and artistic development, her family lived with her father’s friend, the poet Metastasio, who was the Empire’s Poet Laureate.

Metastasio connected her with a poor young keyboard teacher living in the upstairs apartment named Joseph Haydn, who she studied with from the ages of seven to ten.

Marianna Martines

She received a fabulous and wide-ranging musical education from several great teachers and eventually began to sing for Empress Maria Theresa.

She became best known for her vocal performances and compositions and wrote many oratorios, cantatas, and choral works throughout her musical life.

It would have been unseemly for a woman of her social class to make money as a performer, so she made her money composing and teaching, and when her mentor Metastasio died, she inherited a portion of his estate.

Duchess Anna Amalia of Brunswick-Wolfenbüttel (1739-1807)

Duchess Anna Amalia was born in 1739 in Wolfenbüttel in present-day Germany.

When she was sixteen, she married the Duke of Saxe-Weimar-Eisenach. The following year, she had a son named Karl August. Shortly afterwards, her husband died, leaving her a widow and also her infant son’s regent.

As her son grew, she focused on making the court in Weimar intellectually and artistically brilliant. It became known as the “court of the muses” and hosted German cultural giants like Goethe and Schiller.

Duchess Anna Amalia of Brunswick-Wolfenbüttel

She somehow found time to write music herself, including harpsichord sonatas, vocal works, a symphony, and even two operas!

The most famous of the two operas was Erwin und Elmire, based on a libretto by Goethe, and composed in 1776, the year after her son reached his majority and she retired from the role of regent.

Maria Theresia von Paradis (1759-1824)

Maria Theresia von Paradis’s father was Imperial Secretary of Commerce and Court Councilor to the Empress Maria Theresa, and he named his daughter after his boss. When she was a toddler, she lost her sight, resulting in lifelong blindness.

Maria Theresia von Paradis

She was extremely musically gifted, and because of her family’s connections to the court, she received first-rate training in singing, keyboard playing, and composition. Her memory was astonishing: she was said to have sixty concertos memorised.

She went on tour to London and Paris in 1783, at the age of 24, and made a big impression. She even played piano concertos by Haydn and Mozart.

Later in life, she focused on composition herself, using a specially made composition board to write the music out. She wrote a wide variety of works, from piano sonatas to operas. Unfortunately, many of these works remain lost.

Louise Reichardt (1779-1826)

Unusually for the time, Louise Reichardt was born to two composers: both her mother and father wrote music. Her father and grandfather worked at the court of Frederick the Great.

Tragically, her talented mother died when Louise was just four. Her father became overwhelmed by his work and raising Louise and her siblings, so he didn’t spend much time teaching her music. However, she seems to have learned, anyway, and while she was still a child, he published works that included contributions by her.

Louise Reichardt

When she was a young woman, Reichardt struck out on her own to make a living in Hamburg, where she became a freelance musician, teacher and conductor of the Hamburg chorus. However, she never conducted publicly; conducting was seen as an unseemly activity for a woman.

She was most famous for her lovely lieder, which she wrote for the emerging middle-class market.

Maria Szymanowska (1789-1831)

Maria Szymanowska is sometimes referred to as the female Chopin, but since she was born before him, maybe we should think of Chopin as the male Maria Szymanowska!

She was born in Poland to a prosperous family. We don’t know much about her musical training or her early life, but we do know that she got married to a lawyer named Józef Szymanowski in 1810. They had three children together but were divorced in 1820.

Maria Szymanowska

Interestingly and unusually, her performing career began during her marriage, when she was a young mother. She toured through Europe and was extremely well-received. She made a final move to St. Petersburg in the late 1820s and died there in a cholera epidemic.

She wrote over 100 pieces for piano, many of them for the domestic market, a la Louise Reichardt.

Her music is right on the cusp of the transition between the Classical and Romantic Eras, and their uniquely Polish tinge predicts the nationalism that would appear in the piano music of Chopin and Liszt.

It’s a tragedy that she didn’t live longer, but it’s a joy to listen to the great music that survives.

Franz Liszt, Born 22 October 1811: The “Other” Works for Piano and Orchestra

by Georg Predota, Interlude

Apparently, Liszt also composed a 3rd Piano Concerto, possibly before the first two. This concerto was basically unknown until 1989, but it was identified and assembled from multiple sources by Jay Rosenblatt. It had long been assumed that they were early drafts of Liszt’s Piano Concerto No. 1, but since Liszt never mentioned a third concerto in his writing, the existence was unknown. That work premiered in 1990, but it remains little known and little played.

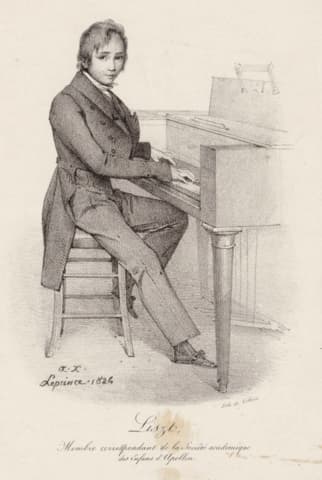

Franz Liszt

Concertos aside, Liszt wrote a number of works for solo piano and orchestra, mostly during his teenage years. In fact, these pieces are probably his first attempts at orchestral writing, combining the forces of the piano and the orchestra. As we celebrate Liszt’s birthday on 22 October, we thought it might be fun to listen to these pieces rarely featured on concert programs today.

Malédiction, S121/R452

Liszt wrote at least two concerti for piano and orchestra in his teens. However, they were never published, and the manuscripts were presumed lost or ignored. Such is the case with the single-movement concerto for piano and strings known as Malédiction. It was started in 1833, revised in 1840, then forgotten and published only in 1915. Actually, the origins of the work might be traced back to 1827, when sixteen-year-old Liszt played a concerto in London. The great pianist Ignaz Moscheles described it as having “chaotic beauties,” but all traces seem to have been lost.

Liszt did not provide a title for the work, but when the composer received the manuscript from the copyist, he inserted certain descriptive romantic phrases over different sections of the music. The opening theme, which was later taken over in the Années de pèlerinage, is labelled “Malédiction” (Curse), while the second theme area is marked “Orgueil” (Pride).

Liszt would later reuse this theme in his Faust Symphony. A calmer section carries the direction “Pleurs, angoisse” (Tears, anguish), and he identifies the codetta as “Raillerie.” The work is unusual as it features only strings in the orchestra, but as John Lade writes, it is “a remarkable succession mood sketches showing a striking, even unexpected unity in performance.”

Grande Fantaisie Symphonique (on themes from Berlioz Lélio)

The young Liszt

Franz Liszt and Hector Berlioz first met a few months after the July Revolution, when Liszt attended the first performance of the Symphonie fantastique in the company of the composer on December 5 1830. Berlioz and Liszt developed a warm friendship that lasted the better part of 20 years. Berlioz does speak of Liszt with a good deal of affection in his Mémoires, and he clearly regarded him unrivalled as a pianist. However, he was much more guarded about Liszt’s orchestral compositions.

Liszt did fashion a piano transcription of the Symphonie fantastique, and when Berlioz produced the sequel Lélio, for reciting actors, choruses with orchestra, and voices featuring dramatic monologues, Liszt decided to use two themes to construct a large-scale work in two parts. He titled it “Grande Fantaisie Symphonique,” featuring a full orchestra and a piano part fully integrated into the orchestral texture.

For his fantasy, Liszt uses the ballad for tenor and piano Le pêcheur, and the song for baritone, men’s chorus and orchestra called Chanson de brigands. Liszt writes an imaginative introduction before the first expansive melody finally appears as a piano solo. This theme is developed at length in dramatic fashion and into far-reaching tonalities, and a pianistic explosion leads to the “Brigands’ Song.” Here, Liszt preserves the Berlioz orchestration for a couple of measures before the piano takes over. The theme is developed, and new themes, not from Lélio, appear before a reworked reprise concludes a very confident work by the 23-year-old Liszt.

Fantasy on Themes from Beethoven’s “Ruins of Athens”

Franz Liszt met Beethoven at the age of 11 when he was introduced by his teacher Carl Czerny. The young Liszt played a piece of Ries and a fugue by Bach, which Beethoven told him to transpose. Beethoven apparently told him, “You are one of the lucky ones, as it is your destiny to bring joy and delight to many people.” For Liszt, “it was the proudest moment in my life.” It is hardly surprising that Liszt was to become a tireless champion of Beethoven and his music.

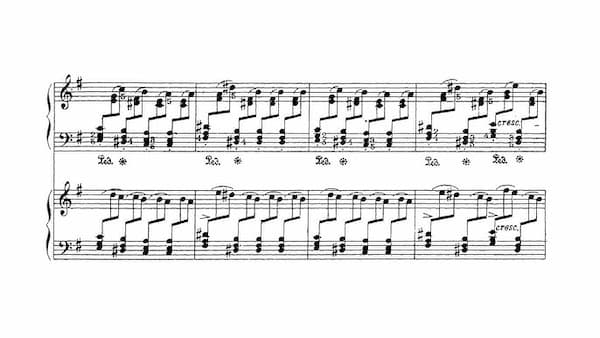

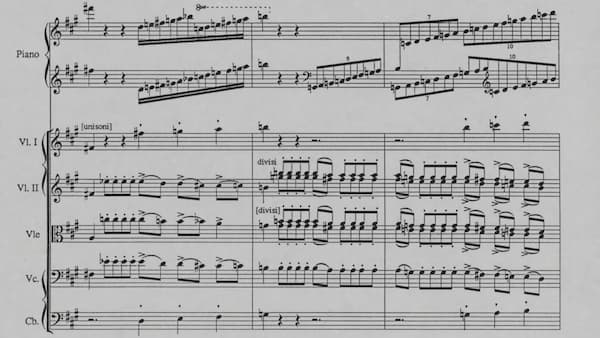

Franz Liszt: Fantasy on Themes from Beethoven’s “Ruins of Athens” music score

Once Liszt had completed the final revisions for his E-flat Major Concerto, he issued his Fantasy on Beethoven’s the “Ruins of Athens” in three different versions: one for solo piano, one for two pianos, and one for piano and orchestra. All three versions are dedicated to Nikolay Rubinstein, and Liszt extracts three Beethoven themes to fashion his Fantasy.

The introduction, exclusively sounded by the orchestra, uses material from the “March and Chorus” section of the original music blended with Liszt’s own “Capriccio alla turca.” The piano takes the lead in the “Chorus of the Dervishes,” while the final section is based on the famous “Turkish March.” Introduced in a very gentle way, with the orchestration, volume and tempo gradually increasing, the coda resounds the other themes. An annotator writes, “For some inscrutable reason, this excellent work is almost never encountered in concert, a fate which seems to have befallen Beethoven’s original, too.”

Fantasia on Hungarian Folk Melodies

Franz Liszt at around 14-15 years old

During Liszt’s lifetime, his Hungarian Rhapsodies were among his most popular works. Liszt writes, “by using the word Rhapsody, I wanted to describe the fantastical-epical nature I believed I had found therein. Each of these works seems to me to form part of a series of poems in which the unity of national enthusiasm is most striking; it is a kind of enthusiasm which can only belong to a single people, whose soul and innermost feelings it represents.”

Originally written for solo piano, Liszt decided to produce a version for piano and orchestra of his Hungarian Rhapsody No. 14. The structure is based on contrasting Hungarian folk tunes, a slow “lassan,” followed by a rapid “czifra” and a whirling “friska.” These individual sections are not strictly delineated but are subjected to constant permutations and the introduction of elements taken from improvisation.

The primary theme is based on a Hungarian folk song entitled “The battle of Mohács,” a melody that Liszt knew rather well. Interestingly, as in the piano concertos, Liszt returns to the opening theme to conclude the work. As he reported with a good deal of pride, “this way of summarising and rounding off an entire piece at its conclusion is really quite characteristic of me.”

De Profundis

Liszt never completed his 3rd Piano Concerto, and his De profundis “Psaume instrumental” belongs in that unfinished category as well. Composed in 1834/35, this elaborated piano concerto was inspired by Liszt’s friendship with the Abbe Felicite de Lamennais, and his rejection of the right-wing aspects of Roman Catholicism. The text clearly references Psalm 130, but the chant itself was composed by Liszt.

Franz Liszt: De Profundis music score

Out of the depths I have cried unto thee:

O Lord, hear my voice:

Let thine ears be attentive,

to the voice of my supplications.

This early concerto already outlines the way Liszt would subsequently formulate his structural ideas. All sections are presented in a single movement, containing a slow passage, a scherzo and a finale based on the transformation of the material used in previous sections. Liszt treated the orchestra with subtlety and sensitivity, and scholars have found “music of stunning originality and a striking instance of Liszt’s early genius.” Liszt had always wanted to complete the work, but life got in the way. It has since been completed by a number of scholars and performers.

Totentanz

Although Liszt never completed his “Psaume instrumental,” he did recycle the chant melody in his first version of the Totentanz. However, the inspiration for Totentanz (Dance of Death) was probably pictorial rather than literary or musical. In 1839, Liszt and Marie d’Agoult visited Pisa and admired the fresco of the Last Judgement. Liszt might have found additional inspiration in a series of wood engravings by Hans Holbein, which Liszt references in a letter to his son-in-law Hans von Bülow, to whom the work is dedicated.

The work is a series of variations on the “Dies irae” theme which Berlioz had famously used in his Symphonie fantastique to portray the sabbath of the witches. A contemporary critic writes, “Its shuddering, clanking rhythms, its sounds as of dancing bones, are of the weirdest achievement possible.” Liszt achieves astonishing dramatic power interspersed by moments of unexpected peace.” And Béla Bartók wrote, “…the work has such a phantasmagorical, dream-like quality that one feels one is in a world in which the strangest things could happen, and no juxtaposition is too bizarre.”

Totentanz was to be Liszt’s final work for piano and orchestra. Shortly after the premiere, Liszt was ready to join a clerical order, and he was thus known as Abbé Liszt for the remainder of his life. I trust you enjoyed this little excursion into the repertoire for solo piano and orchestra by Franz Liszt, a repertoire that combines the extraordinary accomplishments of his pianism with his visionary imagination as an orchestral composer. Happy Birthday!

15 Pieces of Classical Music About Trains

by Emily E. Hogstad, Interlude

All of these sounds, sights, and feelings have inspired composers to create music that continues to resonate with audiences today.

All aboard as we chug through fifteen pieces of classical music about trains!

Eisenbahn-Lust Waltz by Johann Strauss I (1836)

Johann Strauss I (the father of the composer of The Blue Danube) was a well-known composer and orchestra leader who wrote many pieces for various dances and celebrations.

In 1836, he wrote this ebullient waltz (which translates into “Train Ride Fun”) to celebrate the construction of early railroads. They were just beginning to connect communities near Vienna to the city proper.

Mikhail Glinka: Travelling Song from A Farewell to Saint Petersburg (1840)

This work comes from a larger suite of works called A Farewell to St. Petersburg.

Glinka was going through a tough patch at the time, as his marriage was disintegrating (his wife would ultimately leave him for another man). He poured some of his personal feelings about turmoil and transition into this set of songs.

The frantic Travelling Song takes inspiration from the perpetual motion of steam locomotives – and probably the composer’s desire to escape his difficult circumstances!

Charles-Valentin Alkan: Le Chemin de Fer (1844)

Charles-Valentin Alkan was once viewed as one of the greatest pianists of the nineteenth century, but after being passed over for a prestigious teaching position at the Paris Conservatoire, he largely withdrew from public life.

Today, he is best known for his personal eccentricity and the wonderfully original and staggeringly challenging piano music he left behind.

Although Strauss and Glinka’s works came earlier, this is the first work to graphically portray the sounds and motions of a train. It’s sometimes characterized as banal, but no one can deny that it’s fun!

Hector Berlioz: Le Chant des chemins de fer (1846)

Le Chant des chemins de fer translates into Railroad Song.

Somewhat amusingly to modern ears, it’s a whole cantata for orchestra and voices dedicated to glorifying the French railroad (as well as a celebration of the labour of all those who made its construction possible).

The occasion of its composition was the opening of the Gare de Lille, the main railroad station in Lille, France.

Berlioz wrote this work over the course of three nights for the money. He wanted a cannonade to go off in the final chords for maximum drama, but unfortunately, one couldn’t be located in time for his grand artistic vision.

Hans Christian Lumbye: Copenaghen Steam Railway Galop (1847)

Here’s another work composed to celebrate the opening of a railroad. This time, it was the opening of the first railroad in Denmark, which ran between Copenhagen and Roskilde.

Lumbye, a well-known composer of light music, pulled out all the train-based stops here. A bell clangs; whistles go off; percussion instruments unite to imitate the huff and puff of a steam-powered train rushing off to its new destination.

Lustfahrten, Walzer by Eduard Strauss (1879-80)

Like father, like son! Eduard Strauss, like his father Johann Strauss I, also wrote a work to honour the railroad, this one called Lustfahrten, or “Pleasure Trips.”

It was dedicated to the “Comité des Eisenbahnballes” (The Railway Ball Committee). Presumably, every attendee present found it transporting.

The Great Crush Collision March by Scott Joplin (1896)

Here’s one of the stranger entries on this list.

In 1896, a man named William George Crush, an agent with the Missouri–Kansas–Texas Railroad decided it would be a good idea to get rid of two of the railroad’s old locomotives by staging a massive trainwreck and selling train tickets to transport eager spectators directly to the scene of the crash.

A bespoke temporary town was built to accommodate the expected crowds. In the end, forty thousand people showed up!

Unfortunately, the crash turned into a disaster. The locomotives’ boilers exploded on impact, and two spectators died in the aftermath.

This extraordinary event was memorialized by up-and-coming composer Scott Joplin, who wrote a strangely upbeat piano piece portraying the deadly disaster.

Of special note are the notes he wrote in the score: “the noise of the trains while running at the rate of ninety miles an hour” and “the collision” (marked fortissimo, of course).

Pacific 231 by Arthur Honegger (1923)

French composer Arthur Honegger was obsessed with trains. “I have always loved locomotives passionately,” he wrote. “For me, they are living creatures, and I love them as others love women or horses.”

So it makes sense that one of his first big successes was Pacific 231, an imaginative orchestral work that gives the impression of an ever-accelerating train.

It’s easy to tell from moment to moment what stage of its journey the train is in. Six boisterous minutes in, the train decelerates and arrives safely at the station.

Charles Ives: The Celestial Railroad (ca 1924)

New England composer Charles Ives based his piano work The Celestial Railroad on the work of another New Englander: Nathaniel Hawthorne, and his short story of the same name.

In Hawthorne’s story, the narrator takes a train from the city of Destruction to the Celestial City. He begins talking with Mr. Smooth-It-Away, who is an expert on all things Celestial City, despite having never been there before. The story ends with Mr. Smooth-It-Away revealing his true form as a kind of demon. Luckily, in the end, it turns out to be a dream.

This work satirises the utopian and religious movements common in Hawethorne’s day, and Ives clearly enjoyed exploring the story’s themes in his own music.

When Ives wrote his fourth symphony, he adapted The Celestial Railroad into the symphony’s second movement.

Vladimir Deshevov: Rails (1926)

There’s not a lot of information available online about composer Vladimir Deshevov besides the fact that he was born in 1889 and died in 1955.

However, this evocative fleeting portrait of a speeding train deserves a spot on this list, anyway!

Heitor Villa-Lobos: The Little Train of Caipira from Bachianas brasileiras No. 2 (1930)

Translated into rough English, “Bachianas brasileiras” means “Bach-inspired Brazilian pieces.”

Brazilian composer Heitor Villa-Lobos wrote a series of them, combining the European classical tradition with folk music influences from South America.

The finale of the second Bachiana Brasileira is called The Little Train of the Caipira. (A caipira is a person from a more rural area in Brazil.)

This piece follows the caipira’s journey through the countryside of Brazil. It’s up to listeners to decide what happens once the train decelerates and pulls into the station.

Benjamin Britten: Night Mail (1936)

In 1935, British directors Harry Watt and Basil Wright created a twenty-minute documentary about the distribution of mail in Britain. It may have been an unassuming subject, but the work turned into a classic.

Poet and author W.H. Auden was involved with the production and wrote poetry for it. Meanwhile, his creative partner, composer Benjamin Britten, wrote the score.

The two men fused their efforts in this unusual spoken-word piece featuring both Auden’s poetry and Britten’s music.

Bohuslav Martinů: Le Train Hanté (1937)

Czech composer Bohuslav Martinů wrote Le Train hante, or The Haunted Train, in 1937 for that year’s World Exhibition in Paris.

The work isn’t about passenger trains but rather an amusement park train ride, which explains the music’s manic, fairground-like qualities.

Steve Reich: Different Trains (1988)

Steve Reich’s Different Trains was inspired by the fact that, as a Jewish American boy born in 1936, Reich often took train rides across the country to see his relatives. Once he got older, he realised that if he’d been born in Europe at the same time, he might have been forced to ride a train to another destination: a concentration camp.

The work is scored for string quartet and tape. The tapes include interviews with Americans reminiscing about their train journeys and Europeans describing their experiences on trains during the Holocaust. The sounds of sirens, whistles, trains, and even a string quartet were also recorded and woven into the music.

Ian Clarke: The Great Train Race (1993)

Composer Ian Clarke describes this train-inspired showstopper for flute-like so:

Techniques include residual/breathy fast tonguing, multiphonics, singing & playing, lip bending, explosive harmonics and an optional circular breathing section. A forward with explanations of the techniques is given along with fingerings in the score for easy reference. The multiphonics used are of the more friendly variety; seven from only four different fingerings.

It is astonishing to hear how a talented flutist can evoke an entire train with no other instruments present!

Conclusion

These fifteen pieces of classical music about trains have taken us on quite a musical journey. We hope you’ve enjoyed it. Mind the gap as you disembark onto the platform!