Interlude

The 83 Romances by Sergei Rachmaninoff (1873-1943) include some of his finest and most memorable music. They are part of the Russian contribution to the great 19th-century stream of Romantic songs, and the composer cultivated the musical garden he inherited from Glinka and Tchaikovsky. Like Tchaikovsky, Rachmaninoff sought, above all, to capture the basic mood of a poetic text in a bright, melodic image, showing it in growth, dynamic intensity, and development.

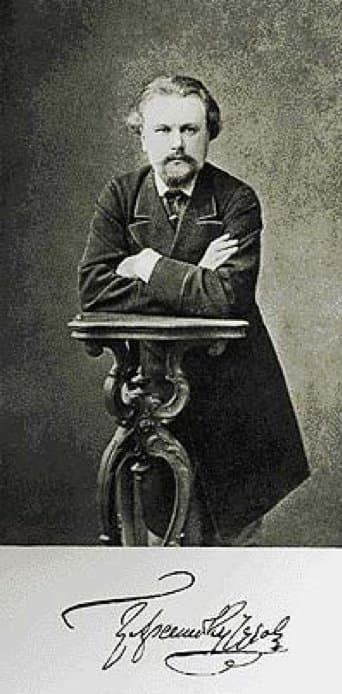

Sergei Rachmaninoff, 1901

Meanwhile, the complexity of the piano accompaniment is dramatic and equal to the “architectonics of a plot-unfolded opera scene.” Combining the declamatory parts for voice with his supreme pianistic gifts, Rachmaninoff’s romanzas were specifically written for the Russian milieu. Once he left Russia for good at the end of 1917, he composed no more Russian songs.

6 Romances, Op. 4

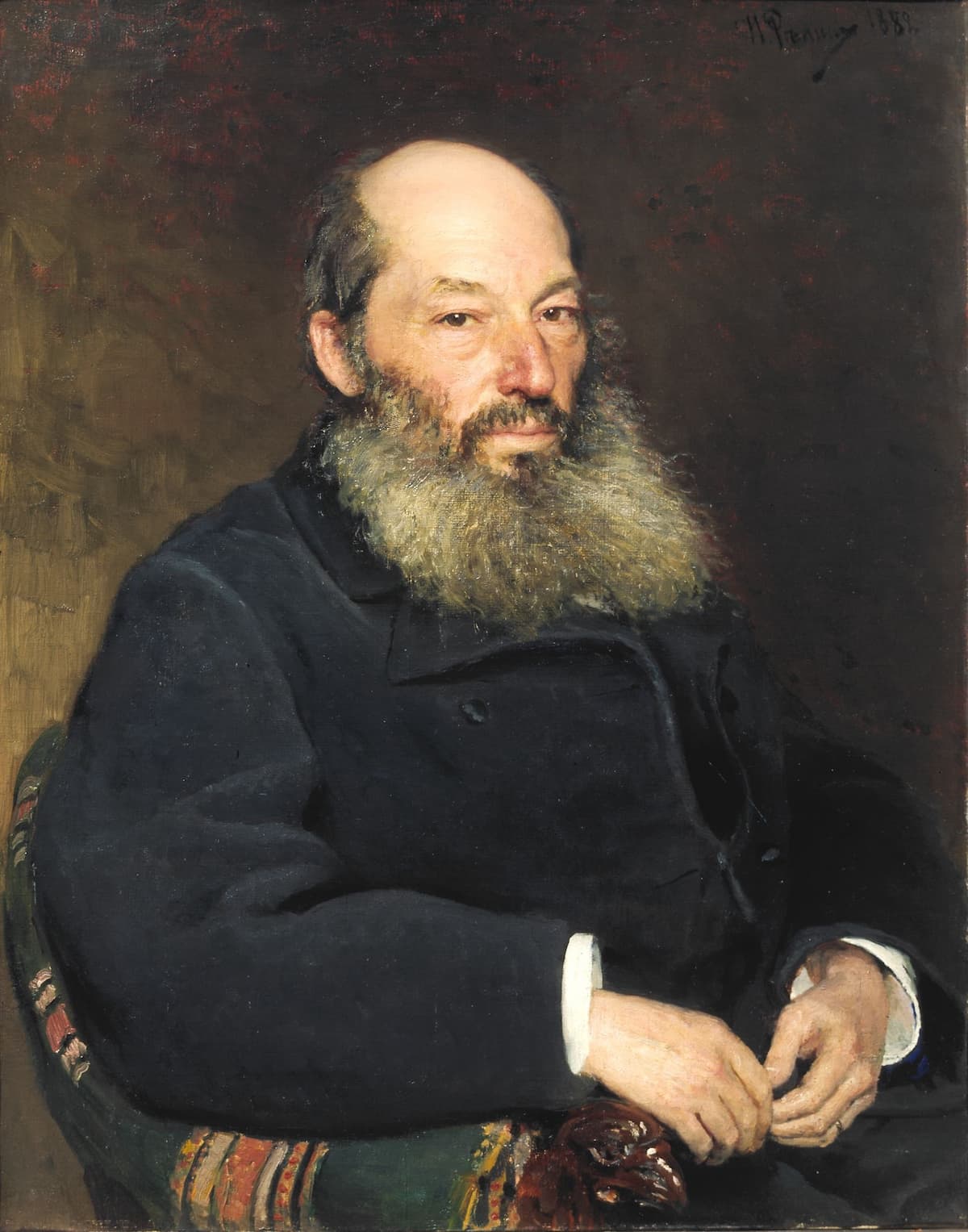

Arseny Golenishchev-Kutuzov

The Six Romances, Op. 4, date from 1890 to 1893, and Rachmaninoff’s student years in Moscow. Demonstrating characteristically idiomatic keyboard writing, the set is informed by a distinctive clarity of texture as the piano accompaniment envelopes piercing vocal melodies of Schubertian incisiveness. “How long, my friend,” based on a poem by Arseny Golenishchev-Kutuzov, features expansive melodic lines and subdued pianistic colours.

Has it been so long, my friend, since I caught

your sad gaze at our farewell moment?

The ray of that farewell

penetrated my soul.

Has it been so long, my friend, since, blundering alone

in a constricting and strange crowd,

I rushed to you, distant beloved,

In a sad dream?

My desires faded… my heart ached…

Time stopped… my mind was numb…

Has it been so long ago, this calm?

But a whirlwind of reunion came rushing…

We are together anew, and the days rush along

As in a flying sea of waves,

And thoughts boil

And songs pour forth from my heart

Brimming over with thoughts of you!

(Trans. Jennifer Gliere)

6 Romances, Op. 8

Afanassi Fet

Rachmaninoff composed music to a substantial number of lyrical texts during his student days. The vast majority of these romances are not included in his first publications, but his choice of poems attests to a wide interest and sure feeling for literary quality. We already find Pushkin, Lermontov, Tyutchev and Afanassi Fet, poets who represent some of the greatest flowering of Russian literature. However, for his second set of songs composed around 1893, Rachmaninoff relied on translations of Ukrainian and German poems.

Four of the Op. 8 set come from Heinrich Heine and Wolfgang von Goethe, and the other two from Taras Shevchenko. The “Water Lily” by Heinrich Heine is a brief two stanza poem of love between the water lilies of the lake and the bright moon above. Rachmaninoff’s setting opens and closes with a delicate but sprightly passage for the piano as the blooming of the lilies greet the moon. The vocal melody is lyrical and highly expressive as the youthful composer presents a warm and affectionate reading of Heine’s poem.

The slender water-lily

Stares at the heavens above,

And sees the moon who gazes

With the luminous eyes of love.

Blushing, she bends and lowers

Her head in a shamed retreat —

And there is the poor, pale lover,

Languishing at her feet!

12 Romances, Op. 14

Fyodor Tyutchev

In the twelve romances of Op. 14, Rachmaninoff strikingly changes the use of the piano. He places significant demands on the pianist, particularly in “Spring Waters”, based on a poem by Fyodor Tyutchev. The words conjure imagery of a violent Russian spring, breaking the ice of winter and threatening to drown the frozen fields. Dedicated to his old piano teacher Anna Ornatskaya, the piano accompaniment rushes forth with unhindered intensity and virtuosity.

White snow still covers all the fields

Yet streams already speak of spring:

Flowing, and waking the sleeping hills

Flowing, and sparkling, chattering all the while.

Proclaiming as they travel, near and far:

‘Spring is coming! Spring is coming soon!

We are the messengers of early Spring

She sent us on ahead, to let you know!

Spring is coming! Spring is coming soon!

Then come the warm and tranquil days of May,

When rosy-cheeked round dances of the young

Will follow in Spring’s train – a merry crowd!’

12 Romances, Op. 21

Sergei Rachmaninoff at 10 years old

During an interview in 1941, Rachmaninoff detailed how extra-musical impressions helped him in the process of creating music. “Ultimately, music is an expression of the composer’s individuality in its entirety,” he explained. “The composer’s music must express the spirit of the country in which he was born, his love, his faith and thoughts that have arisen under the impression of books and paintings that he loves. It should be a synthesis of the composer’s entire life experience.”

In his Op. 21 Romanzas, dating from 1900 to 1902, Rachmaninoff provides a finely controlled balance between voice and accompaniment. And it is once again the piano that offers deep insight into the text. Op. 21, No. 7, “How peaceful,” sets a poem by Countess Glafira Adolfoyna Einerling. The poetess describes a sunset and contemplates the bond between man, nature, and God. Full of gentle lyricism, the music is seemingly simple, but it is easy to hear that the true essence of Rachmaninoff’s musical imagination is already found in these early romances.

How peaceful…

Look there, in the distance

Shines the river like a flame,

The fields lie like a flowered carpet

Light clouds above us…

Here there are no people…

Here there is silence…

Here is only God—and I,

Flowers—and an aging pine,

And you, my dream.

15 Romances, Op. 26

Galina Galina

It took Rachmaninoff almost four years before he returned to setting poetry. The fifteen romanzas of Op. 26 date from the summer of 1906, and they continue to explore some of the declamatory vein introduced in his Op. 21. However, one striking exception is “Before my window,” a poem by Galina Galina nee Glafira Mamoshina. She began writing poetry at the age of 9, and her first poems were published in 1895. She also published a significant number of children’s works, both poem and prosaic, notably two collections of fairy tales. The poetry of her first years is dominated by love lyrics and subjects of spiritual experiences. With consummate skill and imagination, Rachmaninoff weaves a beautiful lyrical line between the voice and the piano.

The cherry tree flowers by my window,

Pensively it flowers in its silver raiment…

And its fresh and fragrant bough

Inclines to me and beckons me…

Blissfully, I inhale in the joyful breath

Of its quivering, airy blossoms,

Their sweet aroma clouds my mind,

And they sing wordless songs of love…

(Trans. Philip Ross Bullock)

14 Romances, Op. 34

Alexander Pushkin

The majority of poems in Rachmaninoff’s Op. 34 was suggested to the composer by Marietta Shaginyan. Of Armenian descent, she grew up in Moscow under privileged circumstances and became one of the most prolific women writers in Russian literary history. She had a lifelong fascination with music and a very close friendship with Rachmaninoff.

As he writes, “Dear Dee, what if I ask you to find me some lyrics for the love songs I’m writing now? Something tells me you must know a whole lot, if not everything, about this. And I would rather have something sad because I’m really not good at writing cheerful things.” The first song of Op. 34 is a text from Pushkin titled “The Muse.” The set also includes the famous “Vocalise,” a song without words, written for a singer of very different gifts, Antonina Nezhdanova, whose lucid tones and light, elegant coloratura had been delighting Moscow Bolshoy audiences.

6 Romances, Op. 38

Antonina Nezhdanova

Rachmaninoff was satisfied and extremely happy with his Op. 34, for “they came to me easily with little trouble. Please, God, that I may continue to work in this way.” However, Rachmaninoff was to write only one more group of songs before he went into exile. Op. 38, written during the Great War in 1916, moves away from the Romantics and turns to Symbolist poetry by Balmont, Alexander Blok, Andrey Bely, Valery Bryusov, and Fyodor Sologub, among them.

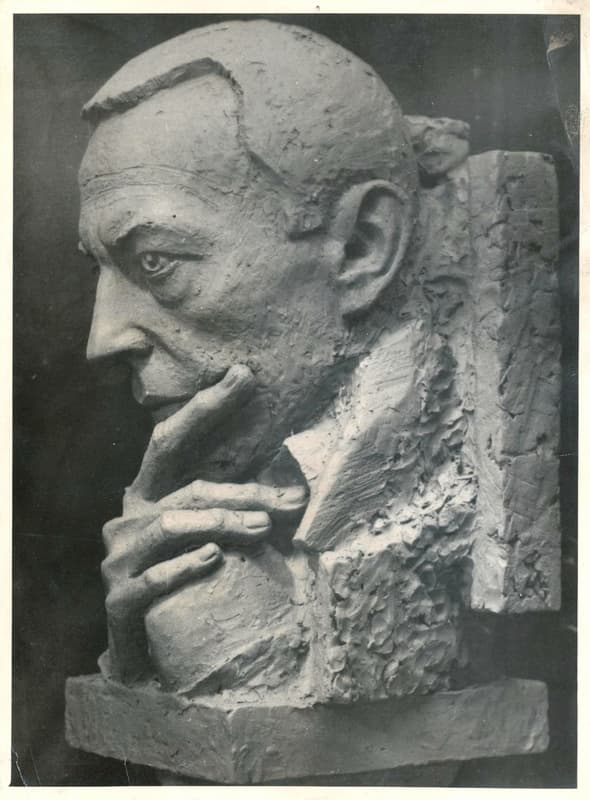

Bust of Sergei Rachmaninoff

Rachmaninoff’s interest in words now took the form not of declamation and its melodic effect but their actual sounds and the implications this had for music. That poetic resonance emerges in almost impressionist textures, and the composer writes, “if everyone wrote nature poems like that, a composer would only have to touch the text, and a song would be made.” “Daisies,” a setting of a poem by Igor Severyanin became Rachmaninoff’s favourite song. Delicately balancing the piano and voice, Rachmaninoff later made a version for piano solo, but he wrote no more Russian romanzas in exile.

Oh, see how many daisies,

Here and there,

They blossom; they are plentiful; they are abundant.

They blossom.

Their petals are three-edged, like wings,

Like white silk;

You are the summer’s might! You are abundant joy,

You are radiant multitude!

Earth prepares to flower with the dew’s draught,

Giving sap to the stalks.

Oh maidens, Oh daisy stars, I love you!

(trans. Elizabeth Wiles)