It's all about the classical music composers and their works from the last 400 years and much more about music. Hier erfahren Sie alles über die klassischen Komponisten und ihre Meisterwerke der letzten vierhundert Jahre und vieles mehr über Klassische Musik.

Total Pageviews

Wednesday, October 5, 2022

Shocking Blue - Venus (DJ Vini remix)

Tuesday, October 4, 2022

Gregorian - Conquest Of Paradise

Faith Hill - There you'll be (lyrics)

Faith Hill - There you'll be (lyrics)

WIND BENEATH MY WINGS (Lyrics) - BETTE MIDLER

Monday, October 3, 2022

Play Always as if in the Presence of a Master

by Frances Wilson, Interlude

Lang Lang masterclass

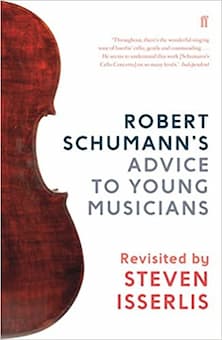

The title of this article is a quote from Robert Schumann’s ‘Advice to Young Musicians’, a cornucopia of practical advice and poetic words of wisdom for young people beginning their musical education, which still has plenty of relevance for musicians of all ages and abilities today.

When we see the word “master” in relation to music, most of us immediately think of the “masterclass”, the private lesson in public where participants submit their playing to the scrutiny of a “master teacher” such as Angela Hewitt or Maxim Vengerov. At one time, such classes were quite terrifying for the participants (I remember watching masterclasses with cellist Paul Tortelier on the TV in the 1970s and 80s and he seemed very fierce!), but in these more enlightened times, the masterclass, sometimes rebranded as “workshop”, has become a valuable forum for critique, support and advice, not only from the “master” but also from active listeners – something private lessons do not offer.

Watching a masterclass, especially with high-level players, is an opportunity to watch artists at work. It reveals what musicians do when they practice and often confirms the huge amounts of time and effort which go into refining music – something which is often forgotten when we see musicians performing. One of the most exciting aspects of the masterclass is witnessing breakthroughs and seeing how just a few words from an experienced master teacher can transform the participant’s playing. It’s an exciting and rewarding experience shared by both performers and observers.

Robert Schumann’s ‘Advice to Young Musicians’

© Amazon

In fact, I don’t believe Schumann was thinking of the masterclass as we know it today in his aphorism, but was actually referring to an attitude of mind which should colour one’s practicing and playing at all times. It is a fact universally acknowledged amongst musicians and music teachers that mindless practice is not only unproductive but also unmusical. But if we play “as if in the presence of a master”, we raise our game. In short, what Schumann is suggesting is that one should always play (and I include “practice” in the word “play”) with all one’s critical and artistic faculties fully alert – mindfully, deeply and beautifully. Repetitive practise is important, for sure, but it should be always be both thoughtful and repetitive – and each repetition should be considered and reflected upon. Taking notice of what one is playing – each phrase, dynamic nuance, subtleties of touch, expression, articulation – will result in more efficient and rewarding practice, leading to the kind of vibrant and authoritative playing one would be happy to present to a master teacher. In effect, one is putting into practice the habits of a master musician; this approach is relevant to from the beginner to the highly advanced player and is one we should carry with us at all times, from the practice room to the performance stage.

For me, Schumann’s comment also suggests one should not fear playing to a master. If you become accustomed to playing with that mindset, what is there to fear?

Friday, September 30, 2022

Morricone conducts Morricone: The Mission (Gabriel's Oboe)

Morricone conducts Morricone: The Mission (Gabriel's Oboe)

Symphony No. 2, Op 27: III

The Opera in the Symphony: Weber’s Symphony No. 1

We are most familiar with Carl Maria von Weber (1786-1826) from his opera Der Freischütz. Weber’s connections with the theatre began in childhood where he grew up in his father’s traveling theatre. His father, uncle to Mozart’s wife Constanze Weber, had been, with his brother, a member of the orchestra in Mannheim. Weber went on to write other operas, including Silvana (1810), Euryanthe for Vienna (1822-23), Oberon for London (1825-26) and, at his death, left the unfinished opera Die drei Pintos, which was completed by Mahler some 60 years later in 1888.

In 1807, Weber wrote two symphonies. At the time, he was in Carlsruhe working for Duke Eugen, who was himself a talented oboist. The orchestration of the symphonies matches the staff of the duke’s orchestra: a single flute, pairs of oboes, bassoons, horns, and trumpets, but no clarinets. There was the usual string complement, although sometimes the double basses are permitted freedom from being always tied to the cellos.

Weber’s Symphony No. 1 has closer ties with his operatic work than with the changes in symphonic form that Beethoven was experimenting with at the same time. Weber’s work would have fallen right in the middle between Beethoven’s Eroica (1805), his 4th symphony (1807), and his 5th (1807-8).

Just like an opera overture, the first movement starts with a call for attention. The first theme comes in the lower strings and the second theme was for the wind players. Even Weber described the movement as more of an overture than a symphonic movement.

This recording comes from a radio concert in April 1951 from Carnegie Hall in New York, with the New York Philharmonic led by Greek conductor Dimitri Mitropoulos. From 1949, Mitropoulos was co-conductor of the New York Philharmonic with Leopold Stokowski and in 1951 became the sole music director. Under his tenure, the Philharmonic expanded their repertoire, both through commissioning new works and by championing the music of forgotten composers, including, at the time, the symphonies of Gustav Mahler, a task that was taken up by his protégé, Leonard Bernstein.