The biggest songs in West Side Story

It has possibly the greatest musical score of all time, and it’s all based around that ominous, uncomfortable tritone… but which songs are really the best? Here’s our definitive ranking* of Bernstein’s songs from West Side Story.

*Tears were shed and friendships ruined in the making of this listicle.

A Boy Like That

A duet between Anita and Maria, this is Anita’s final piece of wisdom for her sister-in-law, before Tony’s (spoiler alert) sticky end. The tempo constantly flits between 3/4 and 4/4 time, creating a feeling of unease. More than anything, it just makes us think: why didn’t Maria just listen to wise old Anita? It would have saved her a lot of upset.Cool

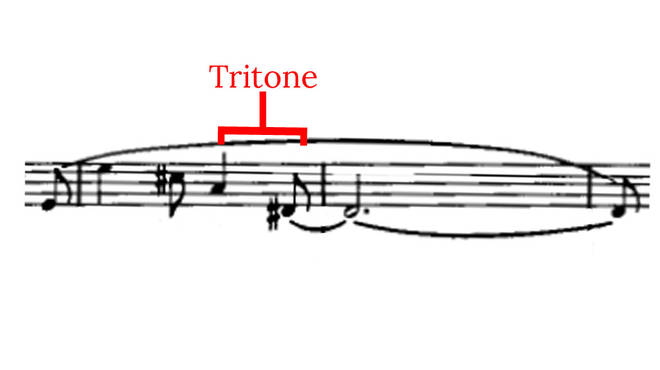

The tritone, also known as the , is frankly everywhere in – so this is by no means the only example of it on this list. ‘Cool’, like ‘Maria’ and ‘Gee, Officer Krupke’, is based around the devil’s interval, and it creates a dark, stilted atmosphere to tell the audience that something is up. (It’s not that we don’t like ‘Cool’, by the way, it’s just Bernstein wrote too many bangers.)I Feel Pretty

In eighth place, it’s Maria’s solo ‘I Feel Pretty’. It’s a bit twee, but the song will always be charming, sweet and one of ’s most memorable melodies.Lyricist Stephen Sondheim described the idea behind this song as “simple’. The New York Times elaborated, saying that Sondheim “said he was never particularly fond of his lyrics in ‘West Side Story’, especially ‘I Feel Pretty’.”Jet Song

Tritone klaxon! In the ‘Jet Song’, the juicy interval appears prominently, but is never resolved. By leaving it unresolved, Bernstein builds that uncomfortable, ominous atmosphere that will set the tone for the rest of the musical.Gee, Officer Krupke

‘Gee, Officer Krupke’, the great comic number in the musical, is a perfect example of Bernstein and Sondheim’s incredible teamwork. It kicks off in a light, vaudeville style, before launching us into another whopping great tritone in the first interval.Tonight

Ah, those sweet teenage dreams of finding a Shakespearean man to sing to us on our parents’ balcony... In their first love duet, Maria and Tony are suspended in time, while the rest of the world fades away. Oh, and there are no tritones here – only nice, loved-up fourths and fifths. *swoons*Maria

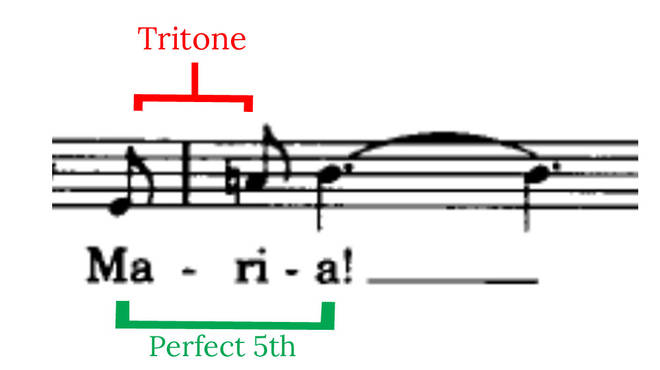

There’s no greater example of the tritone than in ‘Maria’. After that echoed build-up (which makes it sound a bit like poor Tony is lost in a train tunnel somewhere) a great big tritone comes in as Tony exclaims Maria’s name aloud for the first time.But the mood here couldn’t be further from the menacing feeling the tritone normally creates – and that’s because it’s only there for a moment, before it resolves to create a lovely perfect fifth interval.Something’s Coming

In third place, it’s the musical’s tagline. Full of jumpy rhythms, ‘Something’s Coming’ is based on a syncopated ostinato, which is repeated throughout. It sets the tone for Tony becoming disillusioned with gang violence, and his desire to leave the Jets.America

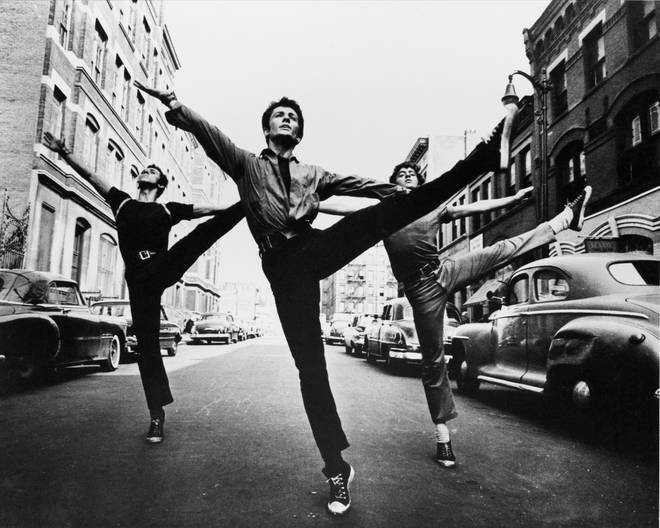

Grab your castanets! ‘America’ is the biggest dance number in the musical, and Sondheim’s rhyming game is exceptional here. Beginning with triplets, it paints a nostalgic picture of Puerto Rico, before moving into 6/8 time and that earworm-y C major melody.Somewhere

‘Somewhere’ has probably found the most fame outside of the musical – and at least a smattering of our Bernstein-shaped tears can be attributed to this final, heartbreaking love duet.It borrows the tune from the slow movement of ’s ‘Emperor’ Piano Concerto, but the final note is shifted a tone higher, hinting at a brief moment of hope for the star-crossed lovers.