National Flag of Mexico

That particular incident started the Mexican War of Independence, which lasted until 1821. At that time, Spain withdrew and recognised Mexico as an independent country. Father Hidalgo is known as the Father of Mexican Independence, and every year on 16 September, the President of Mexico rings the 200-year-old bell and recites the “Grito de Dolores” speech. We thought it might be fun to celebrate Mexican Independence Day by featuring 10 of the most famous Mexican Composers.

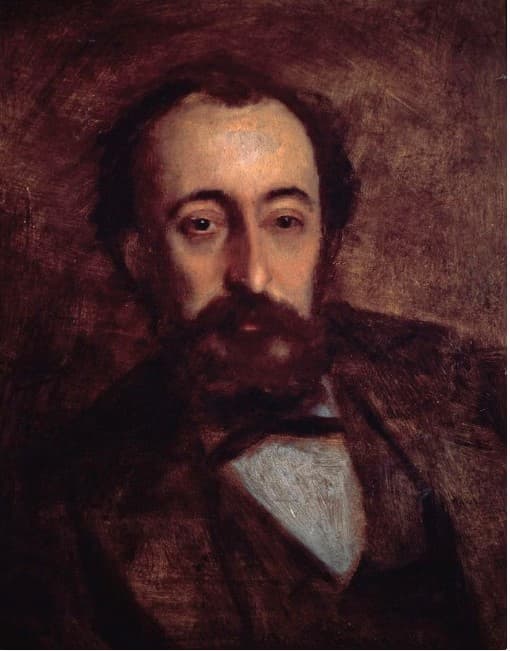

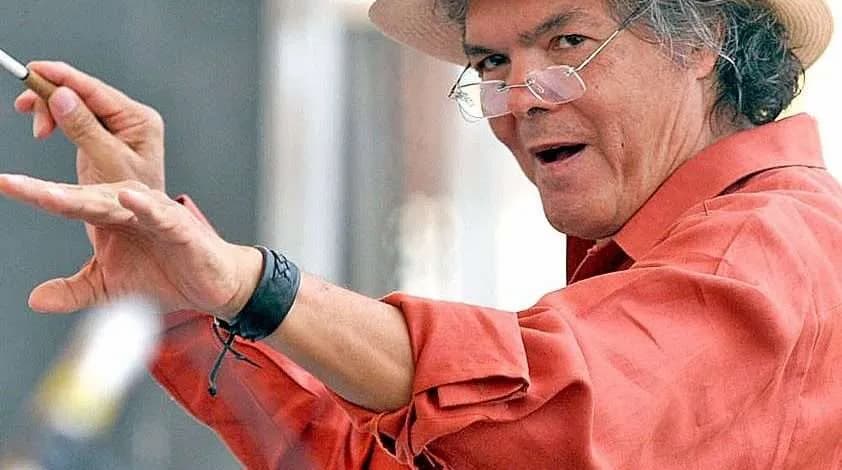

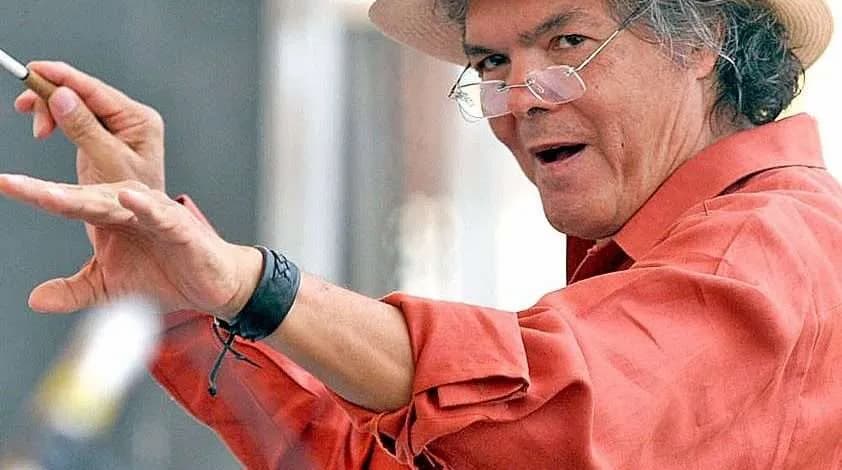

Arturo Márquez

Arturo Márquez

Let’s get started with one of the most popular and most important Mexican composers of his generation, Arturo Márquez. Born in 1950 in the colonial town of Álamos deep in the Sonoran desert, Márquez has “always been enthralled by the music bubbling out of cafes and dance salons in Mexico.” Music had been in the ancestral DNA of his family, and he initially studied the violin and several other instruments as a teenager. Scholarships saw him further his education in Paris and at the California Institute of the Arts. Surprisingly, Márquez was virtually unknown outside his native Mexico until the early 1990s.

When Márquez was introduced to the world of Latin ballroom dancing, he responded with a series of pulsating “Danzones.” A fusion of dance music from Cuba and the Veracruz region of Mexico, Márquez quickly thrilled his audiences with its entrancing and seductive rhythms. His most famous Danzón No. 2 was commissioned by the National Autonomous University of Mexico, and because of its popularity, “it is often called the second national anthem of Mexico.” In fact, Márquez composed a series of “Danzones,” which are increasingly being used for ballet productions throughout the world. You can easily hear why Arturo Márquez is on my list of the 10 most famous Mexican composers.

Aniceto Ortega

Aniceto Ortega

Let’s continue with a composer born shortly after Mexico achieved independence. Aniceto Ortega (1825-1875) was the youngest son of the prominent literary figure and statesman Francisco Ortega, who was active in the Mexican independence movement. He studied medicine and graduated in 1845. He had a distinguished career in medicine and was also a founding member of the Sociedad Filarmónica Mexicana.

Simultaneously, Ortega had a career as a musician. A scholar writes, “at the Gran Teatro Nacional on 1 October 1867, a military band and 20 pianists united in a grandiose performance of his march, the Zaragoza dedicated to the hero who defeated the French. Ortega composed a couple of other marches, but he is also known for his opera Guatimotzin, a setting dealing with the defence of Mexico by the last Aztec ruler Cuauhtémoc. Apparently, it was one of the earliest Mexican operas that used a native subject.

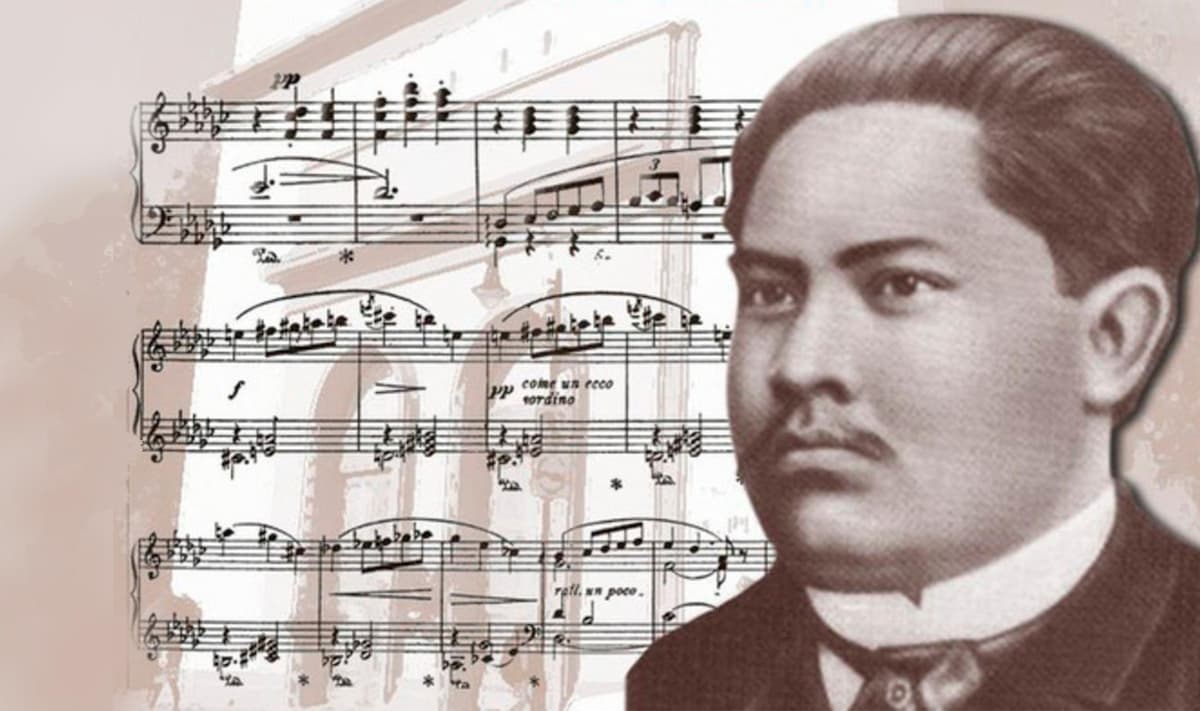

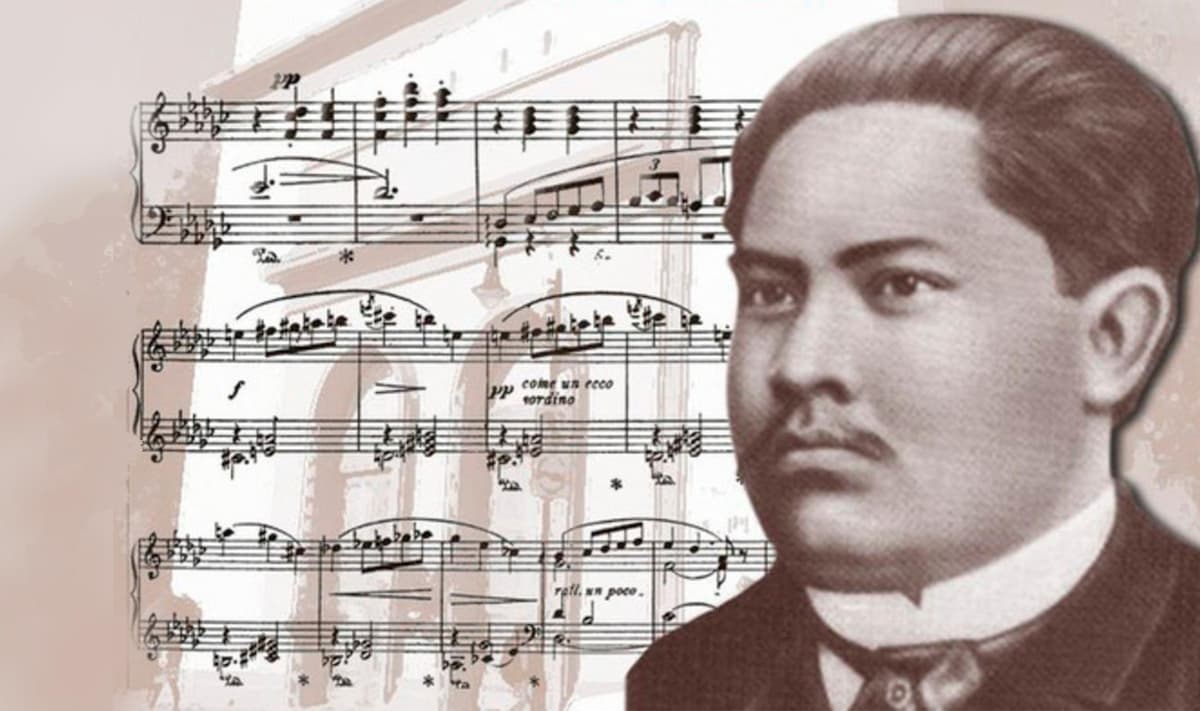

Felipe Villanueva

Felipe Villanueva

One of the best-known Mexican musicians, the violinist, virtuoso pianist, and pianist Felipe Villanueva (1862-1893), was the voice of Mexican musical romanticism. He was born during the historical period known as the “Porfiriato,” a period ruled by General Porfirio Diaz. He ruled the country with an iron fist continuously for almost 20 years, but the fraudulent 1910 election broke his grip, and Diaz was forced to resign and go into exile. His glowing legacy was a decade of regional civil war known as the Mexican Revolution.

Felipe Villanueva was a musical prodigy who composed a patriotic cantata for piano and four voices at the age of 10. He quickly followed up with a number of works for piano and he was accepted into the National Conservatory of Music at the age of 11. Only three years later we find him as a professional violinist performing with the orchestra of the Teatro Hidalgo. José Ramírez writes, “Villanueva developed his craft at a time when Italian music predominated in Mexico, coupled with reminiscences of the Viennese waltz introduced to the country in the time of Emperor Maximilian. Villanueva died at 31 and left countless works for piano and the comic opera Keofar.

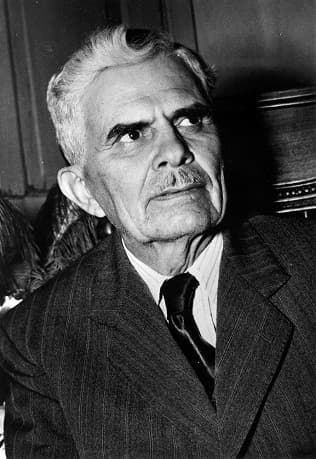

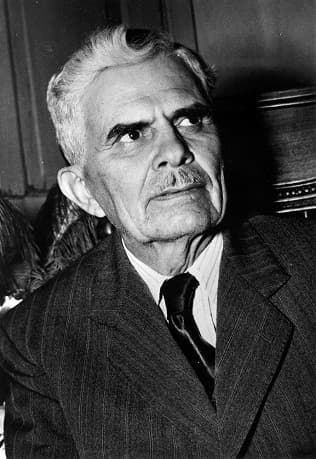

Manuel Ponce

Manuel Ponce

The Mexican pianist and composer Manuel Ponce (1882-1948) was one of the leading Mexican musicians of his time. He was born into a musical family and continued his studies in Europe with Cesare Dall’Olio, Puccini’s teacher. Ponce also studied in Berlin for a short period of time before taking up piano teaching posts at home. He returned to Europe to study with Dukas until 1933 and founded several music magazines. Ponce worked closely with Segovia, and once he returned to Mexico, he became director of the National Conservatory and founded the chair of folklore at the National School of Music.

Ponce made significant contributions to the development of a Mexican national style, evolving away from Romanticism, “nationalism and the use of popular Mexican themes towards a more personal and contemporary style.” He is also credited with the revival of the guitar repertory and using the guitar as a concert instrument. But let’s not forget that he was an accomplished pianist who wrote many piano works that combine Lisztian virtuosity with popular Mexican tunes or phrases inspired by Mexican songs. Ponce is probably best known for his song Estrellita, but the catalogue of his works is vast and embraces a whole spectrum of musical genres and styles.

Silvestre Revueltas

Silvestre Revueltas

Silvestre Revueltas (1899-1940), alongside Carlos Chávez, did much to promote contemporary Mexican music. He studied at the National Conservatory in Mexico City, St. Edward’s University in Austin, Texas, and the Chicago College of Music. Revueltas was an exceptional violinist, and he became assistant conductor of the National Symphony Orchestra of Mexico. Revueltas wrote a good deal of chamber music, including 4 String Quartets, orchestral and film music. He scored the 1939 film La noche de los mayas, which became one of his best-known compositions.

Arguably, Sensemayá is one of Revueltas’ most famous compositions. It is based on a poem by the Cuban poet Nicolás Guillén invoking a ritual Afro-Caribbean chant performed while killing a snake. We meet the leader of rituals known as “mayombero,” who offers the sacrifice of a snake to a god. Revueltas composed a couple of versions starting in 1937, and the music became ever more obsessive. “Finally, it reaches a massive climax by the entire orchestra in what sounds like a musical riot. The coda feels like the final dropping of a knife.”

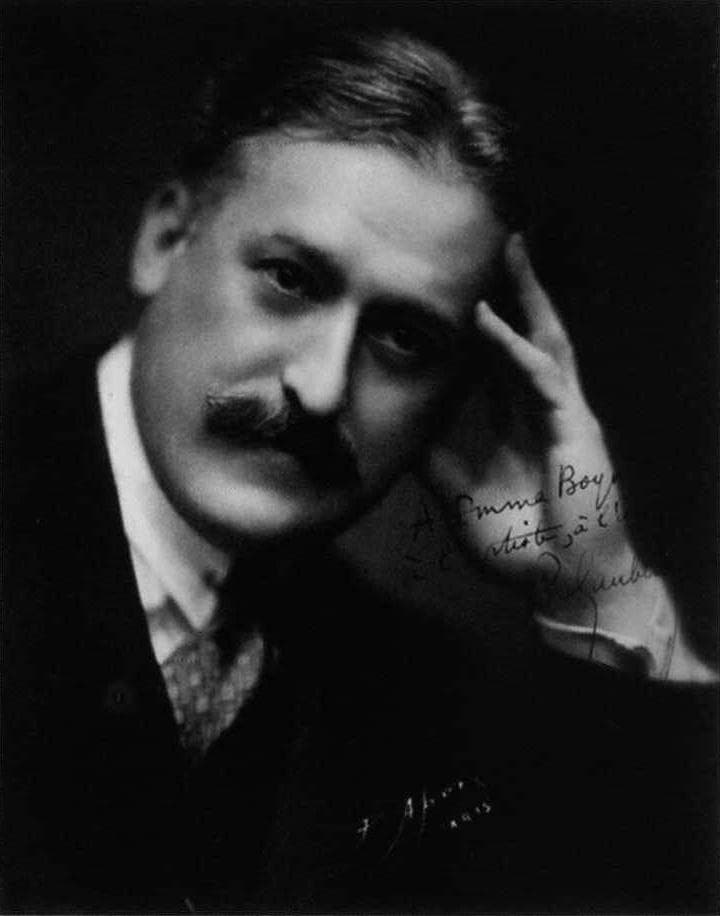

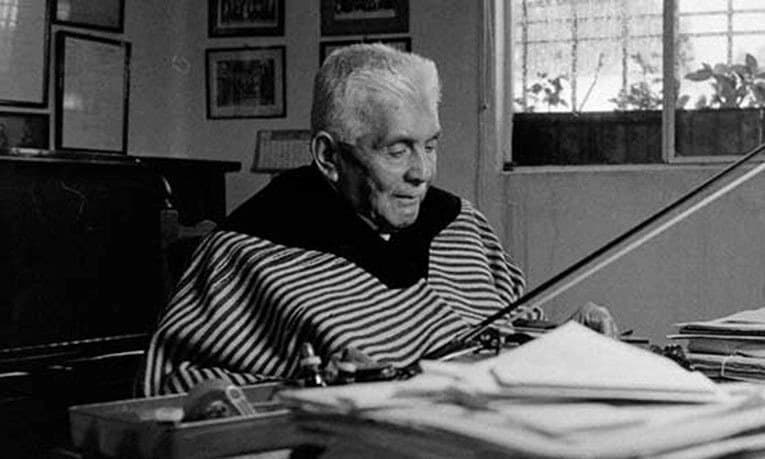

Julián Carrillo

Julián Carrillo

Julián Carrillo (1875-1965) was born into an American family, and his great musical talents saw him study first at the National Conservatory of Mexico City and later at the conservatories of Ghent and Leipzig. Gerald R. Benjamin writes, “During these formative years, he shaped his critical philosophy of the practical application and examination of all theoretical precepts. The results were revolutionary and led him to a lifelong attempt at effecting greater accuracy among the discrepant postulates of physicists, mathematicians and music theorists, and at helping performers to apply, or at least understand them.”

That all sounds pretty complicated, but as I understand it, it applies to a theory of microtonal music created by Carrillo. Termed the “Thirteenth Sound,” Carrillo experimented with his violin and divided the twelve semitones of the tempered scale into multiple parts greater than the 12 classical tones. A biographer wrote, “Carrillo spent his life peering into an unsuspected microtonic world of sound. He has shattered and then remade our chromatic scale, and we might be tempted to call him the atom-splitter of music, except that the name gives no idea of the rich emotional world he has opened.” What is rather surprising is the fact that Carrillo came up with this system in 1895.

Ricardo Castro

Ricardo Castro

Let’s take a break from microtonality and return to the time of Porfirio Diaz and the music of Ricardo Castro (1864-1907). A renowned concert pianist and composer, Castro is frequently considered Mexico’s last great romantic composer. Born in Naza, Durango State, his family moved to Mexico City, and the highly talented Ricardo enrolled in the conservatory. He studied composition with Melesio Morales and piano with Julio Ituarte, and by 1885, embarked on his first international tour that saw him perform in Philadelphia, Washington, and New York. He founded the “Sociedad Filarmónica Mexicana” and completed his opera Atzimba.

Castro furthered his studies with Eugen d’Albert and Teresa Carreño in Paris, and he visited the Bayreuth Festival. Once he returned to Mexico he was appointed music director of the National Conservatory of Music, reforming the curriculum and institute by implementing the latest teaching methods and musical styles. Castro crafted several symphonies, concertos, and countless pieces for piano in a pleasing and sophisticated Schumannesque style infused with Lisztian sparkle and virtuosity.

Gabriela Ortiz

Gabriela Ortiz

Music by Mexican composers continues to flourish, and Gabriela Ortiz is one of the foremost composers in Mexico today. Critics describe her musical language as “achieving an extraordinary and expressive synthesis of tradition and the avant-garde; combining high art and folk and popular music in novel, frequently refined and always personal ways.” She grew up in Mexico City, and her parents were founding members of a renowned music ensemble dedicated to the performance of Latin American folk music. She started composition studies with several renowned Mexican composers and subsequently earned a doctorate in composition and electronic music from City University London.

Her music incorporates seemingly disparate musical worlds, “from traditional and popular idioms to avant-garde techniques and multimedia works.” As one critic wrote, “perhaps, the most salient characteristic of her oeuvre is an ingenious merging of distinct sonic worlds.” In addition, Ortiz allows herself the freedom to celebrate the Mexican folk heritage that played such an important role in her early life, and Atlas-Pumas, with its shifting melodies for violin and marimba, evoke a sonic walk through the streets of Guadalajara.

Candelario Huízar

Candelario Huízar

After his death, Candelario Huízar (1883-1970) was remembered as a hero who rose from humble provincial origins to artistic pre-eminence. As Robert Stevenson writes, “he became a pillar of uncompromising Mexican nationalism in his later works.” Huízar came from a working-class family and was a goldsmith apprentice very early. He taught himself to play the guitar and joined the Jérez municipal band as a saxophonist in 1892. He played viola in a string quartet and was a horn player in the State Band in Zacatecas before entering the Conservatory as a composition student in 1918.

Huízar earned a meagre living in Mexico City when Carlos Chávez invited him in 1928 to join the Orquesta Sinfónica de México as a horn player and librarian. He composed four symphonies, leaving a fifth unfinished and a string quartet. However, he is best remembered for his tone poems. The première of Imágenes, a prizewinning four-movement impression of his hometown, was given in 1929, the fresh carnival piece Pueblerinas in 1931 and the bucolic symphonic poem Surco in 1935.

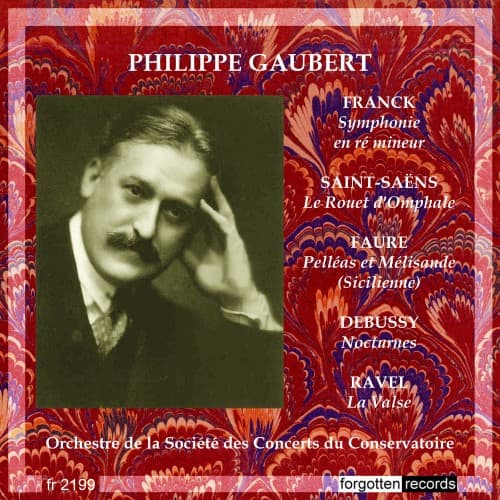

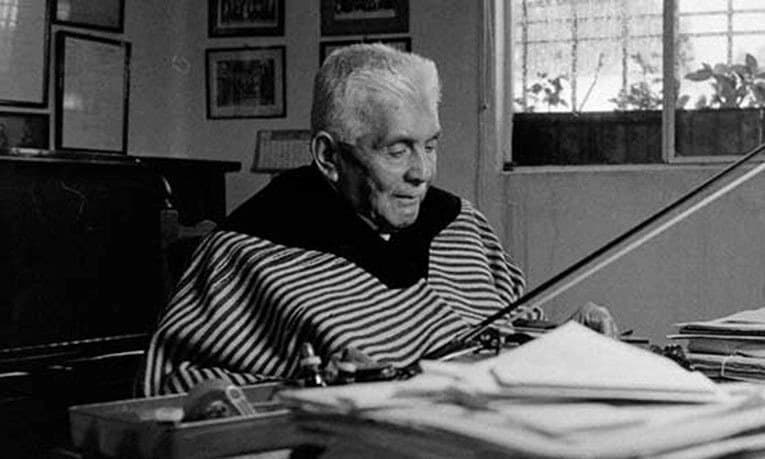

Carlos Chávez

Carlos Chávez

Carlos Chávez (1899-1978) left an enduring legacy to the heritage of his native Mexico. He was born in Mexico City in 1899 and used much of his endless energy to further various aspects of composing, conducting, teaching, writing, and also as a government official. As an ethnomusicologist, he researched extensively the harmonies, rhythms, melodies, and instruments of the Indian cultures of Mexico. Chávez inherited Indian blood from his maternal grandfather, and he wrote, “The most important result was that it gave the young composers of Mexico a living comprehension of the musical tradition of their own country.”

Chávez composed six symphonies, and the second, or Sinfonia India, which uses native Yaqui percussion instruments, is probably the most popular. Composed in 1936, the work is scored for large orchestra and a hefty percussion section. The one-movement work is divided into sections by frequent changes in tempo, cross-rhythms, syncopation, and gorgeous instrumental colour, which contribute to a driving and primal energy. I trust you enjoyed this musical celebration in honour of Mexican Independence Day, and apologies if your favourite Mexican composer did not make my top 10.