It's all about the classical music composers and their works from the last 400 years and much more about music. Hier erfahren Sie alles über die klassischen Komponisten und ihre Meisterwerke der letzten vierhundert Jahre und vieles mehr über Klassische Musik.

Total Pageviews

Saturday, April 6, 2024

Christina Perri - A Thousand Years [Official Music Video]

Save The Last Dance For Me by Emmylou Harris (with lyrics)

Last 'Switch' for PPO's 39th concert season

BY MANILA BULLETIN ENTERTAINMENT

AT A GLANCE

For its finale concert, the resident orchestra of the Cultural Center of the Philippines will feature violinist Diomedes Saraza Jr. as its guest soloist.

The Philippine Philharmonic Orchestra, the country’s primary orchestra, will take its last ‘Switch’ for its 39th concert season on April 19, 7:30 pm, at the Samsung Performing Arts Theater in Circuit Makati.

For its finale concert, the resident orchestra of the Cultural Center of the Philippines will feature violinist Diomedes Saraza Jr. as its guest soloist.

Saraza Jr. is an active concert violinist, chamber musician, and avid educator. The former Manila Symphony Orchestra’s concertmaster, Saraza is a well-established musical artist that has taken part in many international solo performances with different orchestras such as the Mannes Orchestra, New York Symphonic Arts Ensemble, the Sichuan Philharmonic Orchestra to name a few. His extensive solo and chamber performances include prestigious venues that span from Philippines’ Cultural Center of the Philippines, New York’s Avery Fisher Hall, Alice Tully Hall, Carnegie Hall, to Russia’s Tchaikovsky’s Concert Hall among others.

For its final concert, PPO music director and principal conductor Maestro Grzegorz Nowak will take the baton, leading the national orchestra in a night of Fete Francaise. The concert program includes: National Artist Lucresia Kasilag's Violin Concerto No. 1, Camille Saint-Saëns’ Introduction & Rondo Capriccioso, Op. 28, and Franz Schubert’s Symphony No. 5.

An instrumental in developing Philippine music and culture, the National Artist for Music was recognized for including indigenous Filipino instruments into orchestral productions. She has written more than 350 musical compositions that range from folksongs to opera to orchestral pieces. She was the founding mother of the Bayanihan Folk Arts Center for research and theatrical presentations and actively involved herself with the Bayanihan Philippine Dance Company.

Camille Saint-Saëns was a French composer, organist, conductor and pianist of the Romantic era. A child prodigy, he was already giving public concerts as a pianist and organist at a young age. One of his best-known works is the Introduction & Rondo Capriccioso, op. 28. composed in 1863, it was dedicated to Pablo de Sarasate, a Spanish virtuoso violinist, who frequently programmed it in his concert engagements, thus making it popular enough that other French composers made arrangements of it.

Completing the concert finale’s program is Schubert’s Symphony No. 5, a classic piece which is said to pay homage to masters Mozart and Haydn. Schubert deeply admired Mozart. His composition is frequently said to resemble the prolific and influential composer.

Ranked among the greatest composers in the history of Western classical music, Schubert and his work continues to be admired and widely performed. He was a composer during the late Classical and early Romantic eras. He has composed symphonies, masses, and piano works and is best remembered for his “lieder."

Tickets to PPO Concert VIII: Fete Francaise are priced at Php3,000 (Orchestra Center), Php2,000 (Orchestra Side), Php2,500 (Loge Center), Php1,500 (Loge Side), and Php800 (Balcony 1).

The PPO concert season is made possible with partners SSI Group, Inc., TBWA\SMP, Ascott Bonifacio Global City, and Lyf Malate Manila.

For more information, visit the CCP (www.culturalcenter.gov.ph) and follow the official CCP social media accounts on Facebook, X, and Instagram for the latest updates.

Friday, April 5, 2024

I Wanna Grow Old With You - Westlife

Charles Villiers Stanford - Piano Concerto No.2 in C-minor, Op.126 (1911)

Charles Villiers Stanford

by Georg Predota, Interlude

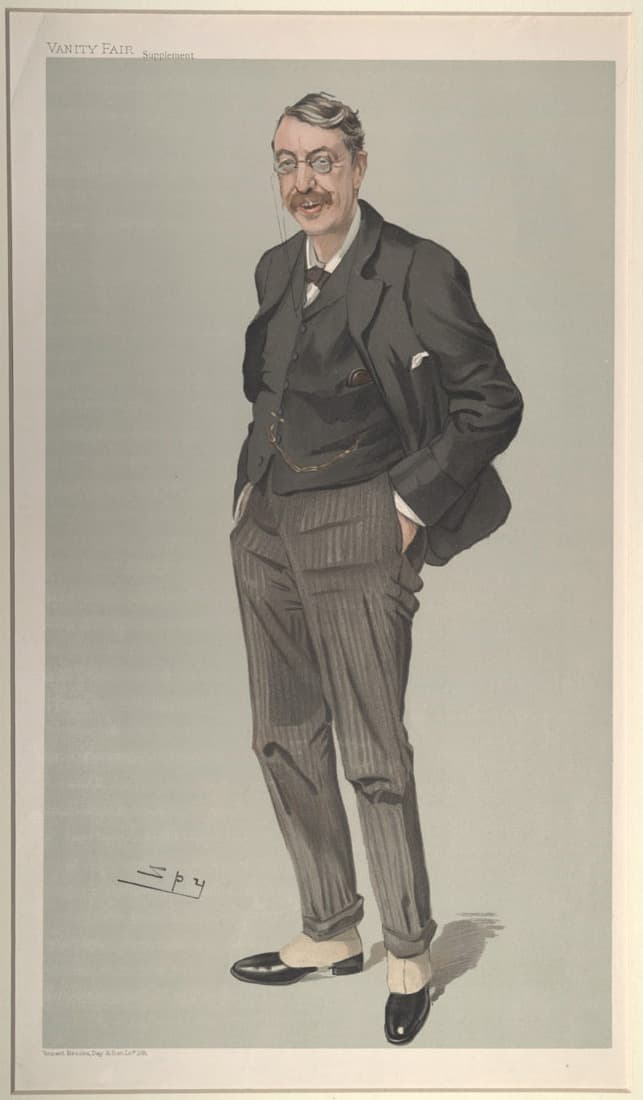

As a composer, Charles Villiers Stanford (1852-1924) might not be a household name, but he is remembered as a teacher of several generations of British composers at the RCM and Cambridge University. However, there is a clear disconnect between how he was celebrated in his day, and how posterity has decided to look at him.

Charles Villiers Stanford

Villiers Stanford was highly lauded during his lifetime as an exceptional composer of large works for chorus and orchestra, and he received a knighthood on the occasion of King Edward VII’s coronation. Posterity, however, has been less kind. The musicologist Robert Stove writes, “Sir Charles Villiers Stanford has not so much been neglected, but posterity has derived malicious satisfaction from ostentatiously yawing in his face.”

Centenary of Death

Villiers Stanford died 100 years ago, on 29 March 1924, and he untiringly campaigned for a national opera, as he saw “opera as a vital catalyst in Britain’s musical renaissance.” He was a mover and a shaker, but his music became associated with Victorian fustiness, worthy if ultimately inconsequential.

As Ralph Vaughan Williams wrote, “in Stanford’s music the sense of style, the sense of beauty, the feeling of a great tradition is never absent. His music is in the best sense of the word Victorian, that is to say, it is the musical counterpart of the art of Tennyson, Watts and Matthew Arnold.”

Critical Assessment

Charles Villiers Stanford as a boy

Villiers Stanford was a busy man. He composed roughly 200 works, including seven symphonies, about 40 choral works, nine operas, 11 concertos, and 28 chamber works. And this is in addition to songs, piano pieces, incidental music, and organ works. Stanford’s technical competence was never in doubt, as the composer Edgar Bainton wrote, “Whatever opinions might be held upon Stanford’s music, and they are many and various, it is always recognised that he was a master of means.”

It’s been suggested by countless critics that Stanford’s music lacked passion. In his operas, critics found music that ought to convey love and romance but fails to do so. His church music is “a thoroughly satisfying artistic experience, but one that is lacking in deeply felt religious impulse. And while Stanford had a real gift for melody often infused with the contours of Irish folk music, he never emulated comic operas but produced oratorios that “only occasionally matched worthiness with power and profundity.”

Beginnings

Charles Villiers Stanford

Born on 30 September 1852 in Dublin, Charles Villiers Stanford was the only child of the city’s most eminent lawyer. He grew up in a highly stimulating cultural and intellectual environment, and his childhood home was the meeting place of countless amateur and professional musicians. In fact, his father was a capable cellist and singer, and his mother an able pianist, with various celebrities such as Joseph Joachim visiting the home.

Stanford showed early musical promise, and he took violin, piano, and organ lessons. His teachers were of the highest calibre, including former students of Ignaz Moscheles. And he clearly had plenty of talent. He gave his first piano recital for an invited audience at the age of seven, presenting works by Beethoven, Handel, Mendelssohn, Moscheles, Mozart, and Bach. Long before the age of twelve, “he could play through all fifty-two Mazurkas by Chopin on sight,” and his earliest composition attempts emerged at the age of eight.

Cambridge and Leipzig

Charles Villiers Stanford’s parents

Not entirely unexpected, Stanford’s father wanted his son to enter the legal profession. Finally, in 1870, Stanford was able to gain the consent of his parents to pursue a career in music. He won an organ scholarship at Queens’ College, Cambridge, and immersed himself in various musical activities. He composed prodigiously and was elected assistant conductor to the Cambridge University Musical Society.

On the recommendation of Sir William Sterndale Bennett, Stanford spent the last six months of both 1874 and 1875 in Leipzig. He studied piano with Robert Papperitz and composition with Carl Reinecke. As Stanford reported, “Of all the dry musicians I have ever known, Reinecke was the most desiccated. He had not a good word for any contemporary composer, he loathed Wagner, sneered at Brahms, and had no enthusiasm of any sort.” To round off his continental study tour, Stanford spent some time in Berlin, working with Friedrich Kiel. “I learned more from him in three months,” he writes, “than from all the others in three years.”

Back in Cambridge

Stanford returned to Cambridge in January 1877, and he quickly became known as a conductor and composer. For one, he conducted the first British performance of Brahms’s First Symphony, and he completed his own First Symphony and the oratorio The Resurrection. He quickly followed up with his Second Symphony and the Piano Quintet, and as the organist at Trinity, he composed “some highly distinctive church music.”

At the age of 35, Stanford was appointed professor of music at Cambridge, with his students including Coleridge-Taylor, Holst, Vaughan Williams, and Ireland. By all accounts, he was not an easy teacher. He only taught in one-on-one tutorials, and “when students went into the teacher’s room, they came out badly damaged.” Apparently, Stanford’s teaching did not follow a prescribed plan or method. “His criticism,” as reported by a former student, “consisted for the most part of “I like it, my boy,” or “It’s damned ugly, my boy” (the latter in most cases).”

Royal College of Music

Stanford joined the staff of the newly inaugurated RCM as a professor of composition and conductor of the orchestra in 1883. He exerted considerable influence on a long list of students, and he instigated an opera class with an annual production. A scholar writes, “Stanford’s enthusiasm for opera is demonstrated by his lifelong commitment to a genre in which he enjoyed varying success.”

Stanford also took on the conductorship of the Bach Choir, the Leeds Philharmonic Society, and the Leeds Triennial Festival. He received honorary degrees from Oxford, Cambridge, Durham, and Leeds, and was knighted in 1902. Stanford continued to be active as a composer as well, but his music was gradually eclipsed by the young Edward Elgar. As Stanford was known as a hot-tempered and quarrelsome man, confrontations quickly ensued with Stanford writing, “Elgar, cut off from his contemporaries by his religion and his want of regular academic training, was lucky enough to enter the field and find the preliminary ploughing done.”

Thoughts on Music and Composers

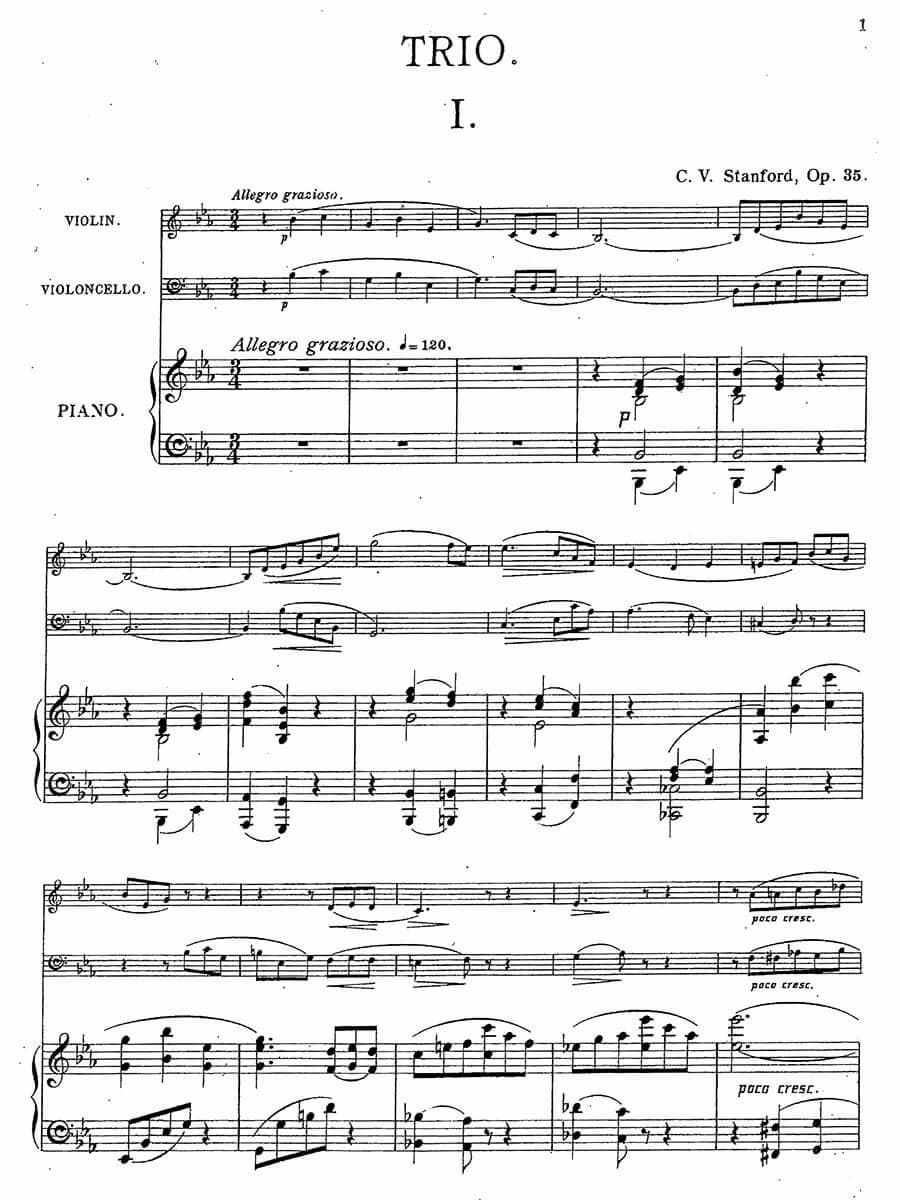

Charles Villiers Stanford’s Piano Trio

In his writings on music, Stanford frequently uses visual metaphors and references to painting and sculpture. His ideas on the subject can be reduced to simple statements. “A piece of music can survive bad texture and instrumentation, but never bad melody or design.” As he famously wrote, “Colour, the god of modern music, is in itself the inferior of rhythmic and melodic invention, although it will always remain one of its most important servants. Fine clothes will not make a bad figure good.”

In the musical culture war of the period, Stanford always sided with Brahms and against the modernists, although he had a great admiration for Wagner. He counted Berlioz and Liszt as lesser practitioners of the musical art, and he most bitterly objected to the music of Richard Strauss. Concerning Debussy and the new French School that emerged in the 1890’s, Stanford was deeply ambivalent.

Stanford was tormented by musical and aesthetic dichotomies at the end of his life. Always wrestling with his status in relation to Irish and English culture, he experienced what Yeats described as “my hatred tortures me with love, my love tortures me with hate.”

On This Day 5 April: Beethoven’s Piano Concerto No. 3 Was Premiered

By Georg Predota, Interlude

The Farmer’s Daughter

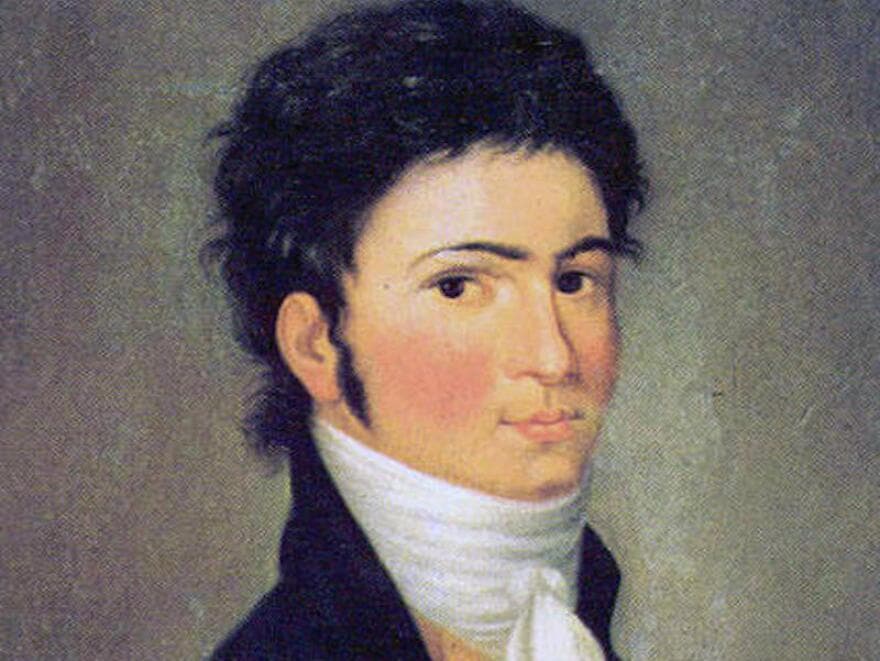

Beethoven in 1801

Beethoven’s landlord had a reputation for drunkenness, and for skirting the wrong side of the law. However, he also had a remarkably beautiful daughter, who had also managed to gain a bit of a reputation. A delightful anecdote reports that Beethoven was greatly captivated by her beauty, and made it a habit to stop his walk and gaze at her when she was working in the farmyard or the field. The farmer’s daughter, however, openly laughed at his clumsy advances.

However, the story isn’t quite finished, as the farmer was arrested and imprisoned for fighting in public. Hoping to impress the beautiful daughter, Beethoven went to the magistrate as an eyewitness to obtain his release. However, other witnesses came forward and refuted Beethoven’s telling of events, with the result that the farmer was forced to stay in jail.

Egyptian Hieroglyphs

Theater an der Wien

Beethoven, it is said, became very angry and abusive and was in danger of being arrested himself. A number of friends came to Beethoven’s aid, and convinced the magistrate of Beethoven’s position in society, his influence, and the power of his aristocratic friends. Having thus escaped jail, Beethoven set to work and drafted parts of a concerto for piano and orchestra in C minor.

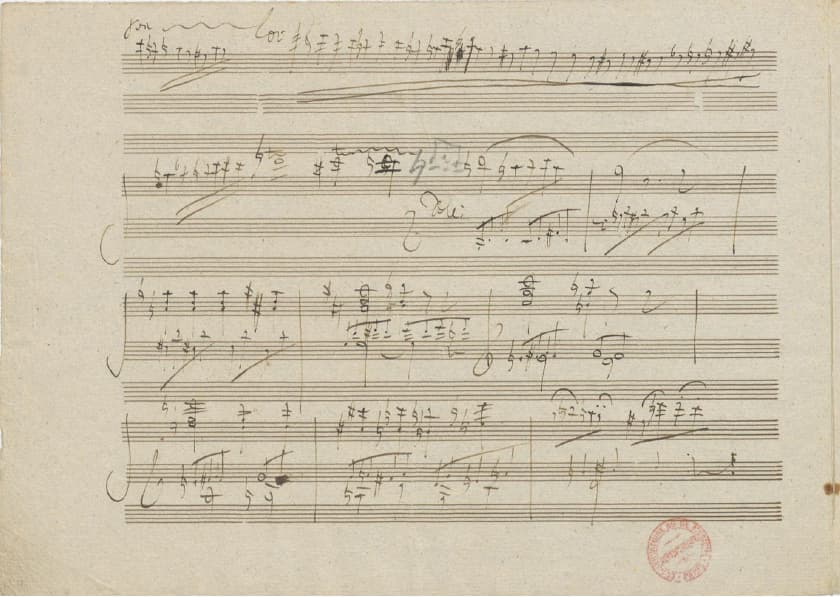

And while the inspiration might well have been Beethoven’s infatuation and ultimate rejection by a farmer’s daughter, the work was still unfinished when Beethoven presented it to the public almost three years later. Ignaz von Seyfried, the new conductor at the Theater an der Wien agreed to turn pages for Beethoven, and he reports, “I saw almost nothing but empty leaves,” he wrote, “at most on one page or another a few Egyptian hieroglyphs wholly unintelligible to me and scribbled down to serve as clues for him.”

As Seyfried reports, “Beethoven played nearly all of the solo part from memory since, as was so often the case, he had not had time to put it all down on paper. He gave me a secret glance whenever he was at the end of one of the invisible passages, and my scarcely concealable anxiety not to miss the decisive moment amused him greatly.” It took Beethoven another year to write out the piano part, and the work first appeared in print in 1804.

First Concerto Maturity

Ignaz von Seyfried

It has been suggested that the C-minor concerto is the first of his five piano concertos that sound like mature Beethoven. But what is more, it also reflects an important advance in piano technology as the range of the instrument had been expanded beyond the standard five-octave span.

The opening “Allegro con brio” pays homage to Mozart’s famous C-minor concerto (K. 491) by imitating the intricate interplay between soloist and orchestra and by launching into a further sparkling development in the coda. Singing with quiet nobility, the piano initiates the “Largo” movement. Imaginative orchestration creates a hushed mood in the remote key of E major and after a magical dialogue between the piano and orchestra, the movements conclude with a typical Beethovenian fortissimo exclamation.

Beethoven’s Piano Concerto No. 3 – original score

Less ornate and more muscular, the concluding “Rondo-Allegro” returns us to the minor key, with a pair of principal themes introduced by the soloist. Alternating passages of exuberant humour and blunt drama the movement irresistibly accelerates with the orchestra providing a high-spirited conclusion.

On This Day 5 April: Herbert von Karajan Was Born

by Georg Predota, Interlude

Herbert von Karajan, 1938

And the music critic Martin Bernheimer called him “the last of the old-school European supermen of music… a genius on the podium.” He was a dedicated devotee of yoga and Zen Buddhism, and characteristically conducted scores completely from memory with his eyes tightly closed. For Karajan, this was not a pose of affection, but “it has to do with the gap between what you want and what you hear and how it becomes narrower.” Karajan explained, “when I was very young and started conducting, I had to train myself to listen to music as it came out because the orchestra of a provincial town was simply noncompetitive with what I had in my ear. This is the point where you begin, and then you take one step and then another, and the gap begins to narrow.”

Heribert Ritter von Karajan, born on 5 April 1908 in Salzburg, has always been tight-lipped about his formative years. As a biographer wrote, “his public is curious to know about his family. But he is not in the least inclined to satisfy such curiosity. In all the conversations that he recorded as part of the present biography, what he had to say about his family would fit on a single piece of paper.”

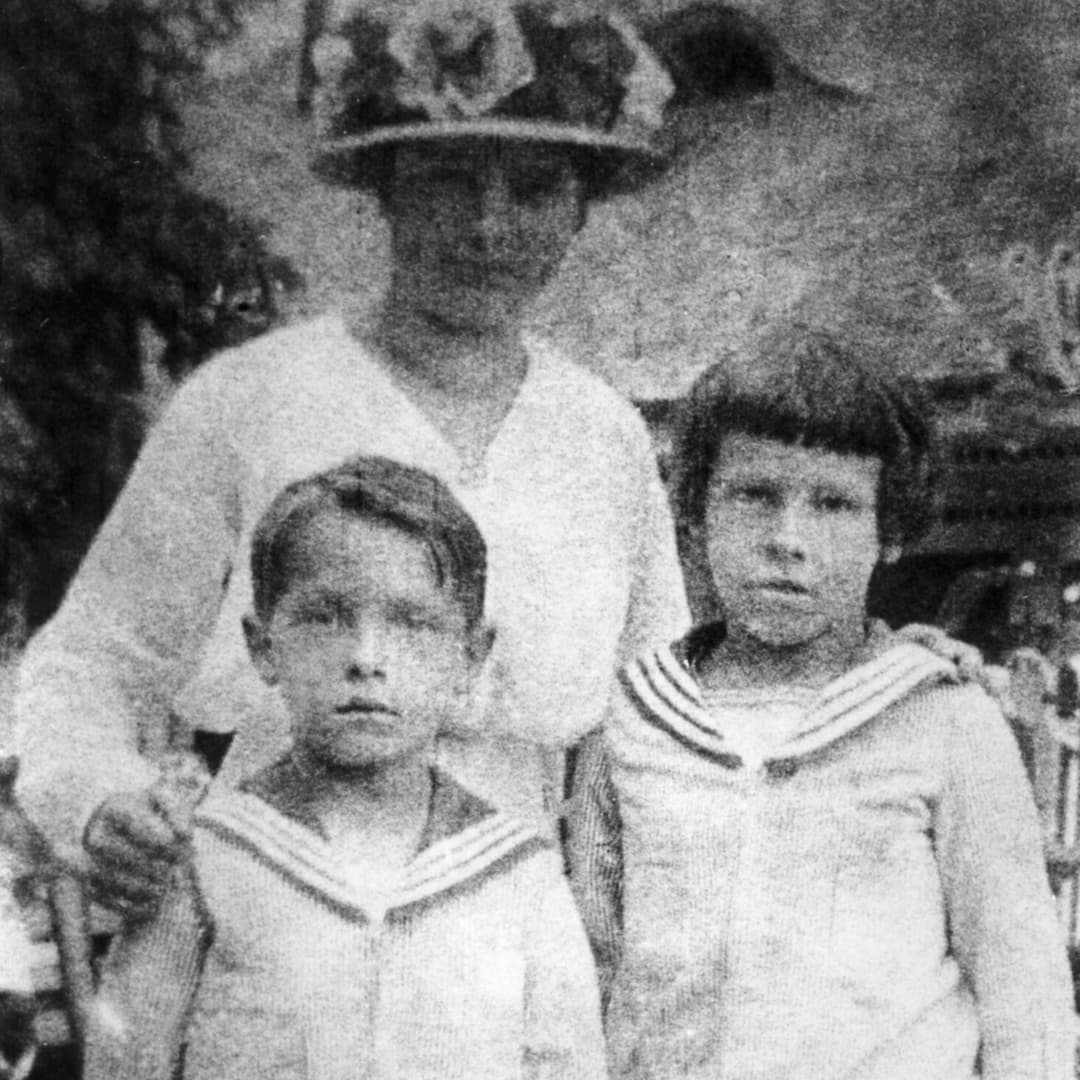

Herbert and Wolfgang Karajan

In fact, Karajan has never given a detailed account of his childhood. This has led to various speculations and theories, with one researcher claiming, “He was not the sort of man to guard sentimental memories or to harbor feelings of resentment.” Karajan clearly had a great number of ghosts in his closet, foremost among them his maintaining silence about his Nazi Party membership. In fact, Karajan joined the Nazi Party twice, first in Salzburg in 1933, and two years later he rejoined the party in Aachen. He subsequently insisted that his interest was “career advancement and survival rather than political conviction,” with Adolf Hitler personally appointing Karajan “state conductor” in Berlin. His enemies called him “SS Colonel von Karajan,” but the de-Nazification board immediately cleared him of any illegal activities, merely banning him from the concert halls for two years.

The Karajans were of Greek ancestry, with his great-great-grandfather Geórgios Karajánnis leaving for Vienna in 1768 and eventually settling in Saxony. He established a clothing business with his brother, and both “were ennobled for their services by Frederick Augustus III. The conductor’s father Ernst von Karajan was a chief medical officer and senior consultant, and his mother Marta née Martha Kosmač, came from a Slovene background. Apparently, Heribert inherited from his father “a seriousness of purpose,” and he once suggested that his mother wanted him to go into banking. That, however, was never going to happen.

Herbert von Karajan, 1941

Karajan’s earliest memory was “hiding behind the curtains, jealously auditioning his brother’s piano lessons.” Wolfgang Karajan was a gifted pianist, but Heribert was extraordinarily talented. It was quickly discovered that he was a child prodigy at the piano. As he later recalled, “I was naturally under a lot of stress from my piano studies alongside my school work. I wasn’t just plonking away. I played in public every year. On the one hand, it isolated you; on the other hand, it gives you a satisfaction it would be very difficult to get from any other source.”

Karajan practiced the piano for four hours every day, and he started attending classes at the Mozarteum in Salzburg in 1914. Within a couple of years, he was working with three eminent teachers, Franz Ledwinka (piano), Berhard Paumgartner (composition and chamber music), and Franz Sauer (harmony). And as the rising star of the Mozarteum, young Heribert made regular appearances in the yearly special Mozart Birthday Concerts. According to contemporary critics, Karajan played with great assurance both of manner and touch, “and a preoccupation with the beauty of sound born of an evidently precocious musical sensibility.”

Statue of Herbert von Karajan in Salzburg

Young Karajan also sang in various local church choirs in Salzburg, and he remembers “that choral singing has in fact accompanied me throughout my life.” Karajan claimed that Bernhard Paumgartner encouraged him to take up conduction, as he “detected his exceptional promise in that regard.” However, Karajan’s’ fascination with orchestral sound had already been identified by Ledwinka. In the event, Paumgartner took Heribert “along again and again to orchestral rehearsals and let him sit alongside him—‘So that you get an idea what conducting is like.’ And he also did his utmost to make sure that I eventually put it all to the test.” On the advice of Paumgartner, and on account of an inflamed tendon in one of his hands, Karajan turned to conducting, taking lessons with Alexander Wunderer and Franz Schalk at the Vienna Academy.