It's all about the classical music composers and their works from the last 400 years and much more about music. Hier erfahren Sie alles über die klassischen Komponisten und ihre Meisterwerke der letzten vierhundert Jahre und vieles mehr über Klassische Musik.

Tuesday, April 2, 2024

Khatia & Gvantsa Buniatishvili - Bach - Concerto for 2 Pianos BWV 1060

Friday, March 29, 2024

Dancing Bach’s St Matthew Passion

by Georg Predota, Interlude

Bach’s St. Matthew Passion

In both works, the text is capable of telling the story all on its own, but Bach adds multiple layers of musical meaning that make it possible to enjoy the music on a number of levels. Bach’s music makes the text and the story come alive, and the compositional complexity and theological depth trigger a wide range of profound emotional responses.

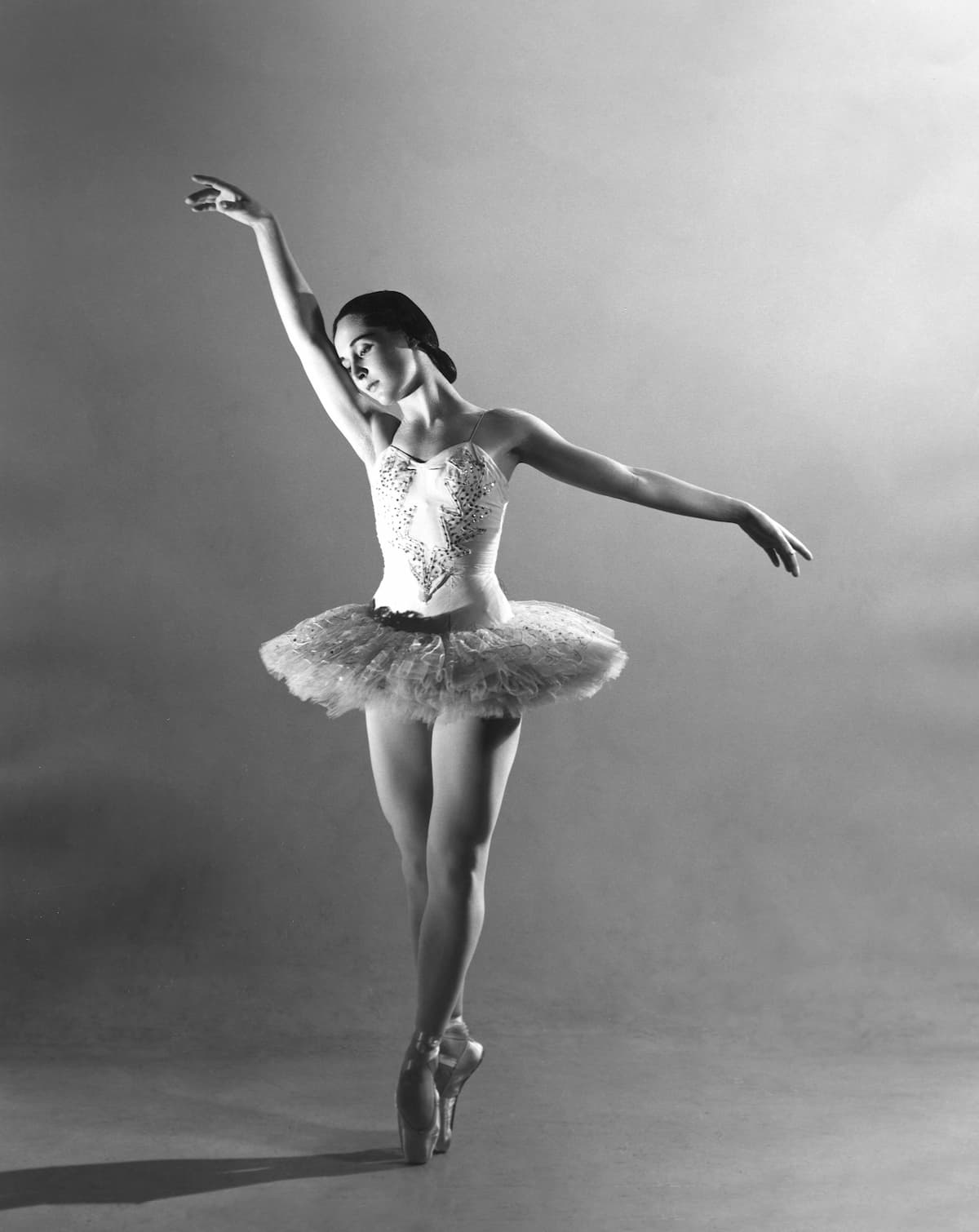

As the Passions are sacred oratorios performed in churches and concert halls, they forgo some important visual elements associated with opera. There are no costumes or scenery, and there is no action. So what happens when one of the single greatest masterpieces of Western sacred music combines Bach’s powerful music and the passion narrative with spellbinding dance performances?John Neumeier

John Neumeier

Transforming the gospel into dance and expressing religious experiences and convictions, has been the life work of the American ballet dancer, choreographer, and director John Neumeier. After a career as a ballet dancer in the United States, Neumeier became director of the Frankfurt Ballet, and subsequently the chief choreographer at the Hamburg Ballet in 1973. He has choreographed more than 170 works, including many evening-length narrative ballets.

John Neumeier’s St. Matthew Passion

Neumeier premiered his St Matthew Passion as a medieval passion play in a Hamburg church before taking it to the Hamburg Opera House. Neumeier’s dancers, dressed in white, embody Bach’s human Passion, with the audience invited to physically and spiritually experience the drama of struggle and redemption. Each dancer expresses grief, doubt, and even aggression, which adds a powerful visual dimension and physical reality to the allegory. Neumeier focuses on the awe-inspiring complexity and universal appeal of Bach’s St Matthew Passion into a profoundly moving experience.

Friederike Rademann

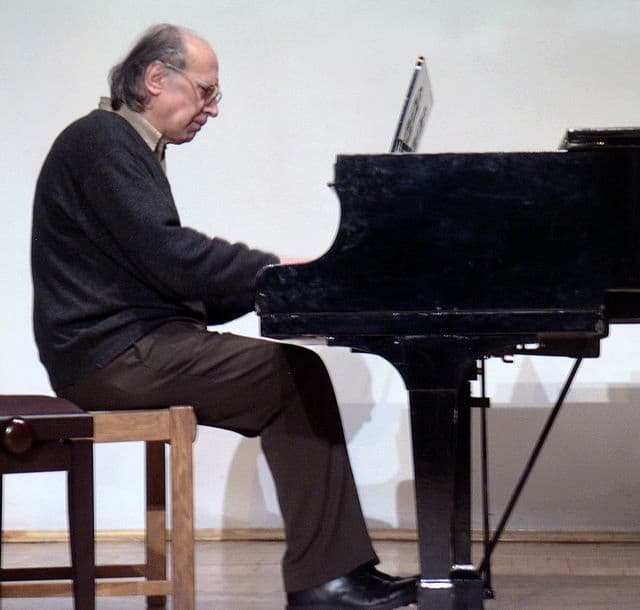

The German choral conductor and teacher Helmuth Rilling is best known for his performances of the music of Johann Sebastian Bach and his contemporaries. He was the first conductor to have twice prepared and recorded the complete choral works of J. S. Bach on modern instruments. Rilling was a student of Leonard Bernstein in New York, and in 1954 he founded the internationally recognized Gächinger Kantorei, which joined forces with the Bach Collegium Stuttgart.

The Gächinger Kantorei is still the ensemble of the International Bach Academy in Stuttgart, and it currently combines a baroque orchestra and a selected number of choristers. The ensemble is under the direction of Hans-Christoph Rademann, and his wife Friederike was a solo dancer at the Semperoper in Dresden. She has devoted herself to expressive dance and developed choreographies for a number of works by Chopin, Ravel, Schumann, and Bach, including the St. Matthew Passion. Her choreography includes the participation of one hundred schoolchildren, who connect and experience Bach’s monumental work as an artistic form of self-expression.

Gloria Contreras

Gloria Contreras

Born in Mexico City, the dancer and choreographer Gloria Contreras was a student of George Balanchine. She taught choreography at the Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México and was director and founder of its choreography workshop. For Contreras, dancing was much more than just a profession, it is “a way of life that teaches a greater understanding of life itself.” Contreras adopted the neo-classical choreographic style of Balanchine, and utilized the music of Mexican composers in her work. However, she also left us a moving choreography of the St Matthew Passion.

Kamea Dance Company

The Passion settings of Bach continue to inspire contemporary ballet productions. One such interpretation, combining music with virtuosic dance movements, comes from the Kamea Dance Company from Be’er Sheva, in southern Israel and the choreographer Tamir Ginz. The title “Matthew Passion 2727” asks the question of what will have happened to this work 1000 years after its premiere in 1727, and what will happen on the way there. Ginz does not translate doctrines, world views, or political statements, but expresses universal human experiences such as suffering and envy, grief and betrayal.

Tuesday, December 19, 2023

Bach For Christmas - A Musical Celebration (Classical Music)

Sunday, December 17, 2023

VOCES8: 'Jauchzet, frohlocket' by JS Bach

Thursday, June 15, 2023

The Widows of Bach, Mozart, and Mendelssohn: What Happened to Them?

by Emily E. Hogstad

However, historians tend to stop following the story once the composer dies. But have you ever wondered what happened to the composer’s families after their deaths? How did their widows keep their composer-husband’s music alive? And in eras before social safety nets, how did they survive…especially if they had kids?

Here’s what happened to three of classical music’s most famous widows after their husbands died:

Anna Magdalena Bach, 1701-1760. Married Bach in 1721.

Anna Magdalena Bach © www.bachueberbach.de

Anna Magdalena had just turned twenty when she married the widower J.S. Bach. In doing so, she became a very young stepmother to four surviving children, aged thirteen, eleven, seven, and three, all from his first marriage. Soon she began having biological children of her own. She would have thirteen in all, with seven dying very young.

When her husband died, Anna Magdalena Bach was forty-eight years old. She had been an accomplished professional singer in her youth, but she was in no position to restart her performing career…not to mention, she still had several minor children to raise!

Unfortunately, Bach hadn’t left enough money for them all to live on. She was left a portion of his estate, but J.S. Bach’s children, including his adult sons who were pursuing careers of their own, also got a cut of the assets, too. And alarmingly, the city of Leipzig only granted Anna Magdalena custody of her children on the condition that she not marry again, guaranteeing their future destitution.

Her stepson C.P.E. Bach was apparently the only child who stepped in to provide financial assistance, but it did not keep her from sinking into extreme poverty. She was evicted from her home and needed assistance from the city government to survive. She died a decade after her husband and was buried in an unmarked pauper’s grave.

Constanze Mozart, 1762-1842. Married Mozart in 1782.

Constanze Mozart

Mozart’s wife Constanze was twenty-nine years old when her husband fell ill and died, leaving her with two children, debts, and few prospects. She roused herself from her grief to line up support for herself, seeking out a pension from the emperor and organizing memorial concerts. She was a singer, and she put her musical abilities to use when she started publishing her dead husband’s works. Eventually, she grew to become a wealthy woman.

Six years after Wolfgang’s death, she took in a tenant named Georg Nikolaus von Nissen, a diplomat, and a writer. Romance blossomed. Rather scandalously, they moved in together the following year. They married in 1809, with von Nissen taking on the role of stepfather and helping Constanze with the administration and promotion of Mozart’s legacy.

Nissen’s last project was a Mozart biography, with which Constanze assisted. Nissen died before it was finished, but she made sure it was published, and it became an important source of Mozart lore. She lived in Salzburg along with two of her sisters, also widowed, and died in 1842 at the age of eighty.

Cécile Mendelssohn Bartholdy, 1817-1853. Married Mendelssohn in 1837.

Cécile Mendelssohn Bartholdy

Twenty-seven-year-old composer Felix Mendelssohn met nineteen-year-old singer Cécile Jeanrenaud in 1836 while he was conducting the Cecilia Choir in Frankfurt. They got engaged that September and were married in March 1837, and had five children together in Leipzig.

Unfortunately, tragedy hit the family in May 1847, when Felix’s beloved sister Fanny died suddenly and without warning of a stroke. Felix was deeply affected by her death, and he died in November 1847, also from a stroke. Cécile was only thirty.

Clara Schumann went to be with her and wrote: “She received me with the tenderness of a sister, wept in silence, and was calm and composed as ever. She thanked me for all the love and devotion I had shown to her Felix, grieved for me that I should have to mourn so faithful a friend, and spoke of the love with which Felix always had regarded me. Long we spoke of him; it comforted her, and she was loath for me to depart. She was most unpretentious in her sorrow, gentle, and resigned to live for the care and education of her children. She said God would help her, and surely her boys would have the inheritance of some of their father’s genius. There could not be a more worthy memory of him than the well-balanced, strong, and tender heart of this mourning widow.”

She kept her two daughters with her and sent her three sons to be raised by her in-laws in Berlin. Her son Felix died in 1851, compounding her grief, and she herself died of tuberculosis in 1853, leaving behind several children aged eight to fifteen.

Friday, May 19, 2023

Brahms on the Road: A Trip to Transylvania with Piano and Violin I

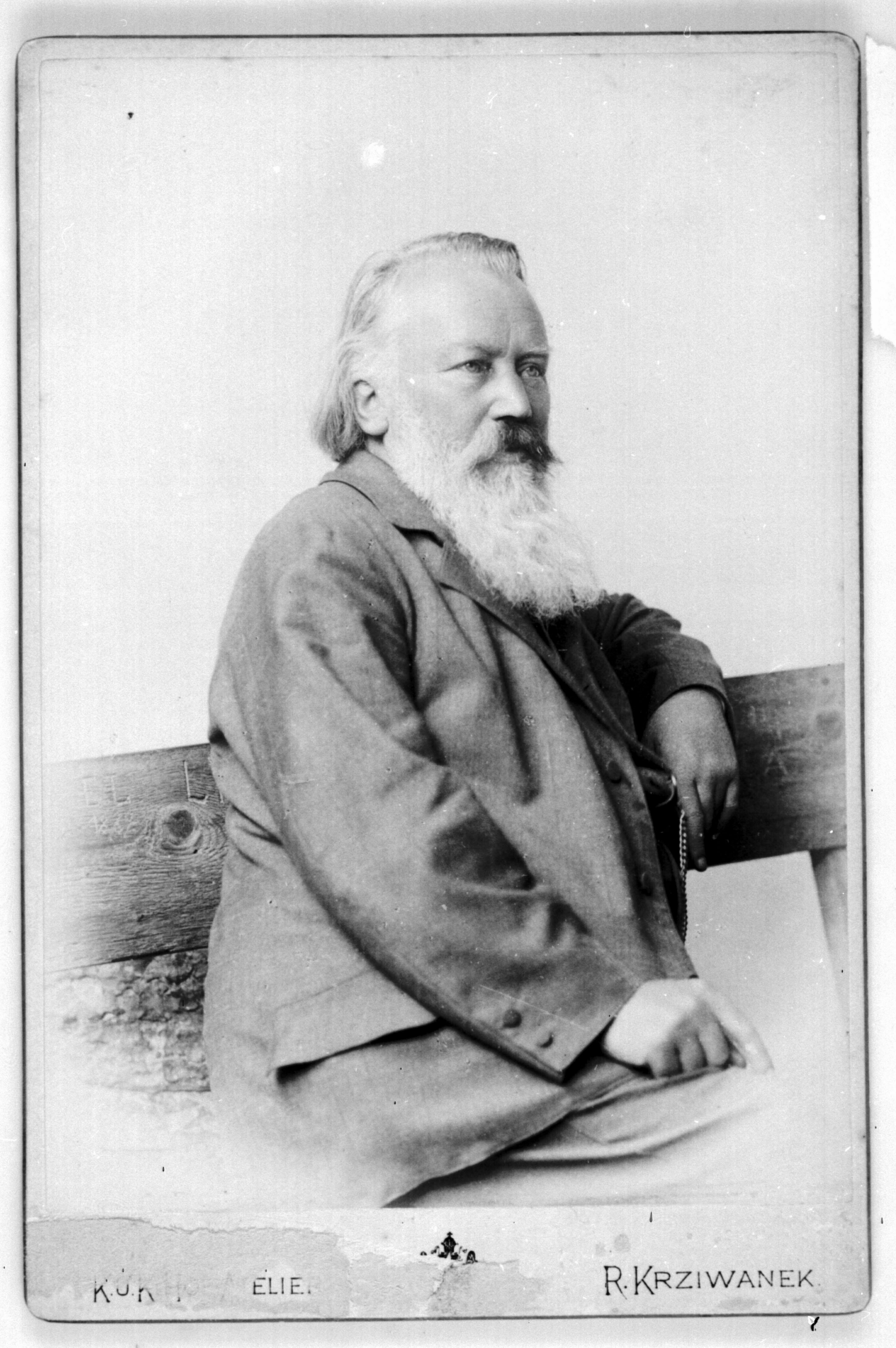

Johannes Brahms

In 1879, Brahms wrote to the librarian at the Gesesllschaft der Musikfreunde that he and the violinist Joseph Joachim were planning a tour to the extremes of the Austro-Hungarian Empire. Could he please send him, with the greatest urgency, some music by Beethoven, Schubert, and a bit of Schumann? Please have this in the mail two weeks ago! If the librarian couldn’t get these out of the library, please buy the Peters edition of the individual works requested and if those aren’t available, the complete violin sonatas of Beethoven and Schubert would do. Quickly!

Brahms was taking to the hinterlands with Joachim for a series of concerts. They were travelling deep into the Austro-Hungarian empire, to the middle of current-day Romania, which for the Viennese-living Brahms, would be like a New Yorker venturing into deepest Iowa.

For Brahms, this was a momentous decision: he hadn’t been on the road touring since the late 1860s when he needed the money, and when he was on tour, he complained about what the constant concertizing did to his fingers. Nonetheless, when Joachim’s agent suggested the tour as a way of combining music making with a holiday, Brahms was interested. Now that he was wealthier and could afford the leisure time, he could travel for the pleasure of it.

Joseph Joachim

It wasn’t easy to convince Brahms to go. Initially, he was reluctant, writing to his publisher Simrock that ‘…all concert tours…are a dubious pleasure.’ He said he wanted to travel in comfort and do some touring, but his concertizing companions, in the past, only wanted to do more and more concerts, scarcely lifting their eyes from the music to admire the scenery, and make money, of course. Eventually, though, he agreed and the tour was on.

Brahms and Joachim had only one day of rehearsal in Budapest, but then they were playing music that they probably knew from memory, having played it together for past quarter-century, with the one exception of a new work. The repertoire they travelled with included works from Bach to Brahms’ latest new work: the Violin Concerto, Op. 77. Joachim was the dedicatee of the work and had played its premiere, which hadn’t been a success. Joachim wanted to take it on the road as he needed to perform it more but Brahms wasn’t certain about reducing the orchestra to piano accompaniment alone. Joachim brought along Mendelssohn’s Violin Concerto as a backup, reminding Brahms that he had learned it from Mendelssohn himself.

The tour started on 13 September 1879 in Budapest, then by train to the city of Arad, just over the border in modern-day Romania. The next morning, off to Timişoara by carriage for a concert, return that night back to Arad, and then off to Sighişoara by train, concert the next day, and off the following day to Braşov. Back to the carriage for a trip to Sibiu, then onto Cluj, returning by train to Budapest on 24 September. This 11-day trip covered 1,600 km (1,000 miles).

The concert in Arad sold out almost immediately. The programme included Schumman’s Fantasiestücke for Piano and Violin (an arrangement of the Fantasiestücke for clarinet and piano), Tartini’s Devil’s Trill Sonata, and works by Bach, Beethoven, and Brahms.

Arad wasn’t quite as desolate and isolated as Brahms had imagined it to be in this tour of remote regions of the Empire. It was an important transportation hub, had a large military establishment, had the sixth music academy on the continent (opening only 11 years after the Royal Academy in London), and was a bustling commercial centre.

Reviewers noted in particular Brahms’ performance of the Schumann Novelletten, which seems to have been Brahms’ first performance of the entire work ever.

Off by single-track railroad to Timişoara, where the concert was promoted as presenting ‘The Piano Hero and the Violin King.’ The concert started with the Beethoven Violin Sonata, Op. 30, and closed with the Brahms Violin Concerto, Op. 77, arranged for violin and piano.

Finally, Brahms’ Violin Concerto was coming in for praise, with one reviewer calling it ‘one of the most important compositions today,’ but wished for an orchestra to accompany, rather than just a piano. Reports of the concert couldn’t understate their importance to the town: ‘anybody who was anyone, by birth, rank, position, anyone with an understanding for music, was present. They held their breath at the wonderful sounds of the Violin King and the rare virtuosity of Brahms, a pianist of the first rank. Stormy applause followed each number; the audience left highly satisfied, conscious of having been present at an evening of rare artistry.’

Friday, March 31, 2023

Musical Prayers for Peace

By Georg Predota

© National Today

In such times of deep political and ideological crisis, it is once again the musical community calling for an end to hostilities and musically praying for peace. And at the head of the class stands once more the celebrated cellist Yo-Yo Ma, appointed by the United Nations a “Messenger for Peace.” Yo-Yo Ma has been reaching out to people all over the globe, inspiring them to address the many challenging social issues we face today. In a recent concert with the New York Philharmonic, he performed a work that Pablo Casals often played to protest war and oppression.

Pablo Casals (1876-1973) was one of the greatest cellists of the twentieth century. He had to flee his native Spain in 1939 when dictator Francisco Franco took control at the end of the Spanish Civil War. Together with thousands of other refugees, Casals was housed in a refugee camp in France. “Casals spent much of his time delivering food and clothing to fellow refugees, and he continued to aid them throughout his life.”

Pablo Casals’ centenary statue

Yo-Yo Ma, at the age of sixteen, played in an orchestra under Casals’ direction. He recalls, “I never forget the way his mind and body would radiate vitality the moment he raised his baton… He saw himself not primarily as a cellist but as a musician, and even more as a member of the human race.” His personal anthem, “The Song of the Birds,” is a traditional Catalan Christmas song and lullaby, and after his exile in 1939, Casals would begin each of his concerts by playing his arrangement for cello.

It might come as a surprise, but the patriotic hymn “Prayer for Ukraine” dates back to 1885, and to a time when Ukrainian culture and language were once again suppressed by the government of Imperial Russia. It has been a very long struggle for independence for Ukraine, as different conquerors have mercilessly fought over this land rich in natural resources and culture. There was a short-lived revolution in 1919 brutally suppressed, and the Soviet occupation inflicted one tragedy after another.

Valentin Silvestrov

During the famine of the 1930s, millions of Ukrainian peasants starved to death because of the criminal policies of Joseph Stalin. The Nazi occupation of Western Ukraine saw the implementation of the “Final Solution,” first applied in cities whose wealth and cultural standing depended entirely on a vast Jewish population. And then there has been this perpetual tug of war over the Crimean Peninsula. Ethnic cleansing at the command of various Russian heads of State was repeated under Stalin, and then once again in 2014 after the Russian occupation. Instead of painting himself as a victim of Western aggression, Vladimir Putin and his shadow puppets should rightfully stand trial for committed war crimes at the International Criminal Court in The Hague.

On 23 February, Anatolii Vasylkovskii took the Ukrainian national chamber ensemble known as the Kyiv Soloists on a regular two-week tour to Italy. One day later, Russian troops invaded Ukraine, and he remembers, “When we arrived in Italy, many of our members phoned their families and heard that there had been bombings.” The focus of the tour changed in an instant, as “we had to spread the message that Ukrainians are peaceful people.” Relying on the solidarity of other ensembles and orchestras, who hosted them in their concert halls and homes, the tour was extended across Europe. Anatolii emphasized, “We want to dedicate these concerts to our families, our country, our army, which are now fighting for the democracy of the whole world.” The Kyiv Soloists want to convey a “message of peace and solidarity with the people of Ukraine and of love for the families and friends they have left behind.” Their performances are no longer simply aimed at cultural exchange and musical enjoyment; they are a form of activism. “Our music-making is now a prayer for peace.”

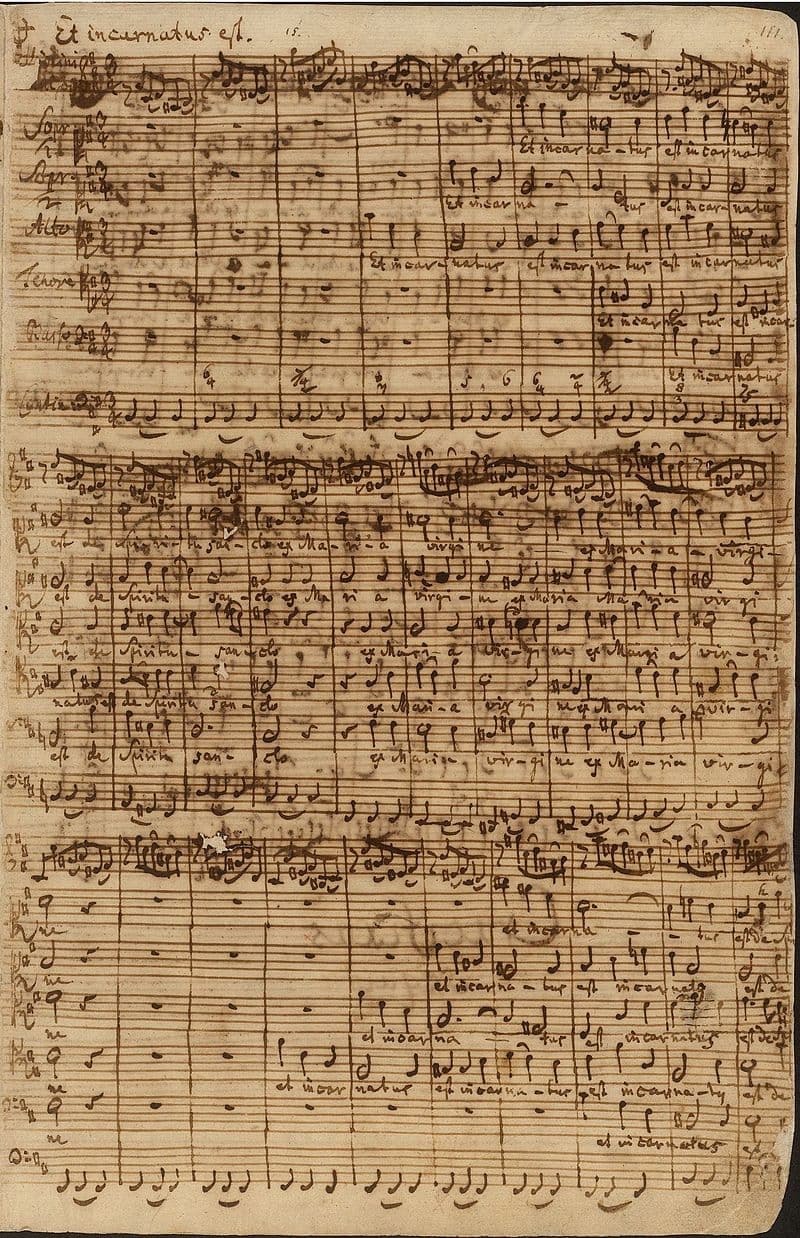

If I may be permitted, let me add my personal musical prayer for peace by turning to the music of Johann Sebastian Bach. In 1817, a critic called Bach’s Mass in B minor “the greatest work of music in all ages and of all people.”

Bach’s B minor Mass, BWV 232

While this kind of assessment might need a bit of clarification, the work is significant because we find a Lutheran composer setting the complete Latin text of the Catholic Mass Ordinary. So, how does a devout Lutheran musically deal with the line in the Creed, “and I believe one holy catholic and apostolic Church?” That particular text receives two melodies sung by the choir simultaneously, and in perfect harmony. One is the traditional melody sung by Roman Catholics, and the other is a Lutheran chorale melody. The language of music, after all, has the distinct ability to console and unite. Let us now join the Bach Collegium Japan in Bach’s short prayer for peace, the “Dona Nobis Pacem” (Grant us Peace) from his B-minor Mass.

Thursday, March 23, 2023

10 pieces of classical music that will 100% change your life

Hold on to your hats – if you haven’t heard any of these musical works of genius, your life is about to be changed 10 times in a row.

Classical music can calm nerves, fire up the senses and spark creativity. It can also be uniquely life-affirming.

Here are the 10 major works we recommend you devote some time to. Needless to say, each of these examples should be digested in a single sitting.

J.S. Bach: St Matthew Passion

What is it?

It’s one of two ‘Passion’ oratorios that have survived since Bach died (he could’ve written up to five), but it’s also become one of his most celebrated pieces. The original title is Passio Domini nostri J.C. secundum Evangelistam Matthæum (the ‘J.C.’ stands for Jesus Christ, which is maybe a bit familiar for someone he hadn’t met… but we’ll let him off).

Why it will change your life:

If you thought that Baroque music mostly dealt with plinky-plinky harpsichords, the St Matthew Passion will change mind. There are biblical proclamations of impending apocalypse littered throughout, and for each of them, Bach works in some sort of crushing atonality or strange chord, as if he’s wincing with pain each time it happens. This is such a human experience, composed at a time when human experiences weren’t chief among the aims of most Baroque composer composers.Tchaikovsky: Symphony No. 6

What is it?

Tchaikovsky’s final symphony, nicknamed ‘Pathétique’. The premiere performance was given just nine days before the composer died.

Why it will change your life:

Tchaikovsky was surely one of the most personally troubled of the great composers – and this symphony was essentially the outpouring of many of his issues, in a way. Many initially thought it was a lengthy suicide note, others pointed to the composer’s torment over his suppressed sexuality, while some thought it was just a tragic, sad, glorious and indulgent artistic expression. But the reason it’ll stay with you forever is that all of these contexts work in their own way, but it never detracts from how magisterial the music itself is. It’s a lesson in the very best ways of expressing emotions through music.Mahler: Symphony No. 2

What is it?

Massive, that’s what it is. Mahler’s Symphony No. 2 (known as the ’Resurrection’) is a 90-minute attempt to put the whole nature of existence into a piece music. So pretty ambitious.

Why it will change your life:

If you think any bit of music over three minutes long is a bit indulgent and full of itself, this single piece will convince you that sometimes it’s completely worth spending an hour and a half on one musical concept – even if it is a huge concept. No other composer could’ve made it more entertaining (listen out for death shrieks!), or more rewarding. The epic final few minutes are a stupidly generous reward on their own, but getting there is half the fun.Beethoven: Grosse Fuge

What is it?

One of the last pieces Beethoven wrote for string quartet, one of his celebrated ‘Late’ quartets. It’s a one-movement experiment in structure that was universally hated when it was first composed.

Why it will change your life:

It’s proof that not only can critics and audiences get it really, really wrong, but also that it’s all about interpretation. You can actually hear the struggle and the effort it must have taken to compose, which means it’s not always a relaxing listen, but few pieces in history have so nakedly shown how a composer can throw absolutely everything into a single work. And, in the end, it was hugely influential to serialist composers of the 20th century with none other than Igor Stravinsky proclaiming it a miracle of music. How about that for delayed gratification?Mozart: Requiem

What is it?

The piece that Mozart wrote on his deathbed, in a furious fever. Well, if the movies are to be believed, anyway.

Why it will change your life:

From the opening Introitus, the mournful tone is set. It might just be us, but doesn’t it actually sound like Mozart is scared of death here? Aside from being spooky as anything, the Requiem is a haunting patchwork of things. Completed by one of Mozart’s pupils, Franz Süssmayr, it’s become a legendary mystery and the perfect way to end the story of one of history’s most celebrated geniuses – in other words, not end it all. What an enigma.Monteverdi: Vespers

What is it?

It’s Baroque genius Claudio Monteverdi’s defining work, a gigantic noise that some argue bridged the gap between the Renaissance and the early Baroque periods.

Why it will change your life:

It makes you realise that just because something’s really old, it doesn’t mean it’s automatically boring, or simply lauded because it was ‘groundbreaking’. Make no mistake about it – Monteverdi’s Vespers are hugely entertaining on their own terms. For starters, it’s simply enormous in scale. If you want to be crude about it (and we do) then you could describe it as Monteverdi taking church music to the opera, with all the drama that implies. Trumpets, drums, massive choruses, florid vocal lines… this really is the greatest hits of the early Baroque.Elgar: Cello Concerto

What is it?

The only cello concerto that Edward Elgar wrote, and one of the most famous concertos of all time.

Why it will change your life:

It’s proof that intense emotion can come from the most unlikely of people. We don’t want to get all mushy on you, but there’s something spectacularly English about how the ultimate stiff-upper-lipped curmudgeon, Edward Elgar, was able to convey his emotions in music rather than in words or actions. His private life was surprisingly tumultuous (that’s another story), and in pieces like the Cello Concerto it’s as if the gasket has blown and Elgar is finally able to let out all the pent-up emotion in a focused blast.Cellist Sébastien Hurtaud plays Elgar Cello Concerto (3rd movement)Played and edited by cellist Sébastien Hurtaud.Wagner: The Ring Cycle

What is it?

It is everything.Why it will change your life:

Realising for the first time that the world of opera could actually be this immersive is a very, very special feeling. Wagner’s whole four-opera cycle has a terrible reputation as simply ‘that exhausting long opera’ – but that perception couldn’t be further from the truth. The Ring Cycle is a fundamentally unhinged work of staggering genius, and the peak of operatic indulgence, excess and excellence. Ignore at your peril.Max Richter: Vivaldi: Recomposed

What is it?

A radical, beautiful re-invention of Vivaldi’s Four Seasons concertos, by modern indie-classical composer Max Richter.

Why it will change your life:

Listening to Vivaldi: Recomposed is like discovering an old jumper that you used to love has magically, miraculously lost all its bobbly bits and is actually at the height of fashion. What Richter manages to do so incredibly well is to subtly sneak in delightful additions, tweaks and reinventions to a classic you already know extremely well, and freshen it up not just for the modern era, but for the eras to come too.Gorecki: Symphony No. 3

What is it?

Possibly the most emotionally draining piece of music ever written.

Why it will change your life:

There’s a reason Polish composer Henryck Górecki called his third symphony the Symphony of Sorrowful Songs. Each movement features a solo soprano singing texts inspired by war and separation, but it’s the second movement that really stands out. The text is taken from the scribblings on the wall of a Gestapo cell during the Second World War and, as you can imagine, it’s pretty harrowing stuff – but Górecki makes it sound so transcendental that it’s hard to believe it was written in such dire circumstances. He said himself that he wanted the soprano line “towering over the orchestra”, and it certainly does that.