It's all about the classical music composers and their works from the last 400 years and much more about music. Hier erfahren Sie alles über die klassischen Komponisten und ihre Meisterwerke der letzten vierhundert Jahre und vieles mehr über Klassische Musik.

Tuesday, April 2, 2024

Khatia & Gvantsa Buniatishvili - Bach - Concerto for 2 Pianos BWV 1060

Friday, March 29, 2024

Dancing Bach’s St Matthew Passion

by Georg Predota, Interlude

Bach’s St. Matthew Passion

In both works, the text is capable of telling the story all on its own, but Bach adds multiple layers of musical meaning that make it possible to enjoy the music on a number of levels. Bach’s music makes the text and the story come alive, and the compositional complexity and theological depth trigger a wide range of profound emotional responses.

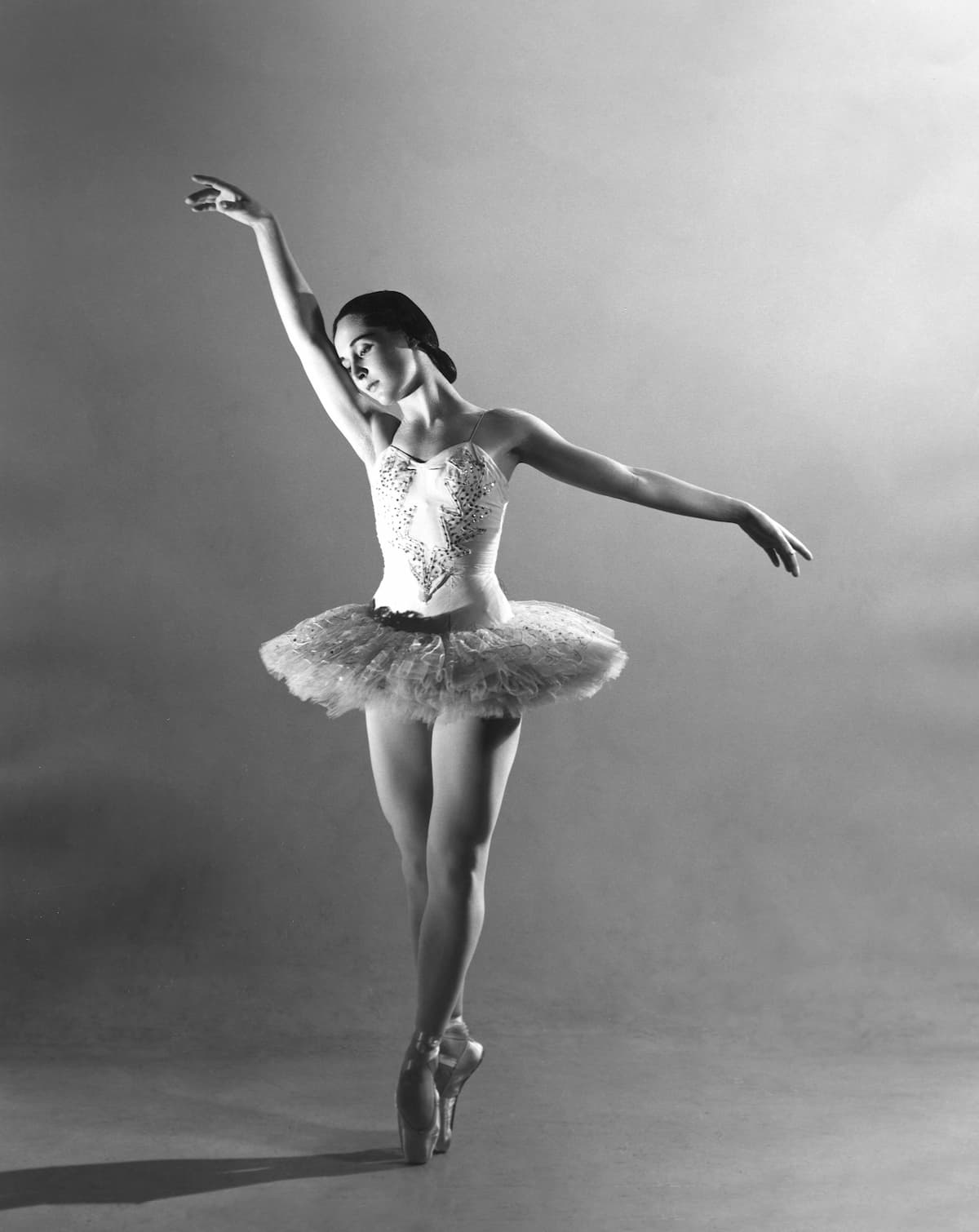

As the Passions are sacred oratorios performed in churches and concert halls, they forgo some important visual elements associated with opera. There are no costumes or scenery, and there is no action. So what happens when one of the single greatest masterpieces of Western sacred music combines Bach’s powerful music and the passion narrative with spellbinding dance performances?John Neumeier

John Neumeier

Transforming the gospel into dance and expressing religious experiences and convictions, has been the life work of the American ballet dancer, choreographer, and director John Neumeier. After a career as a ballet dancer in the United States, Neumeier became director of the Frankfurt Ballet, and subsequently the chief choreographer at the Hamburg Ballet in 1973. He has choreographed more than 170 works, including many evening-length narrative ballets.

John Neumeier’s St. Matthew Passion

Neumeier premiered his St Matthew Passion as a medieval passion play in a Hamburg church before taking it to the Hamburg Opera House. Neumeier’s dancers, dressed in white, embody Bach’s human Passion, with the audience invited to physically and spiritually experience the drama of struggle and redemption. Each dancer expresses grief, doubt, and even aggression, which adds a powerful visual dimension and physical reality to the allegory. Neumeier focuses on the awe-inspiring complexity and universal appeal of Bach’s St Matthew Passion into a profoundly moving experience.

Friederike Rademann

The German choral conductor and teacher Helmuth Rilling is best known for his performances of the music of Johann Sebastian Bach and his contemporaries. He was the first conductor to have twice prepared and recorded the complete choral works of J. S. Bach on modern instruments. Rilling was a student of Leonard Bernstein in New York, and in 1954 he founded the internationally recognized Gächinger Kantorei, which joined forces with the Bach Collegium Stuttgart.

The Gächinger Kantorei is still the ensemble of the International Bach Academy in Stuttgart, and it currently combines a baroque orchestra and a selected number of choristers. The ensemble is under the direction of Hans-Christoph Rademann, and his wife Friederike was a solo dancer at the Semperoper in Dresden. She has devoted herself to expressive dance and developed choreographies for a number of works by Chopin, Ravel, Schumann, and Bach, including the St. Matthew Passion. Her choreography includes the participation of one hundred schoolchildren, who connect and experience Bach’s monumental work as an artistic form of self-expression.

Gloria Contreras

Gloria Contreras

Born in Mexico City, the dancer and choreographer Gloria Contreras was a student of George Balanchine. She taught choreography at the Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México and was director and founder of its choreography workshop. For Contreras, dancing was much more than just a profession, it is “a way of life that teaches a greater understanding of life itself.” Contreras adopted the neo-classical choreographic style of Balanchine, and utilized the music of Mexican composers in her work. However, she also left us a moving choreography of the St Matthew Passion.

Kamea Dance Company

The Passion settings of Bach continue to inspire contemporary ballet productions. One such interpretation, combining music with virtuosic dance movements, comes from the Kamea Dance Company from Be’er Sheva, in southern Israel and the choreographer Tamir Ginz. The title “Matthew Passion 2727” asks the question of what will have happened to this work 1000 years after its premiere in 1727, and what will happen on the way there. Ginz does not translate doctrines, world views, or political statements, but expresses universal human experiences such as suffering and envy, grief and betrayal.

Tuesday, December 19, 2023

Bach For Christmas - A Musical Celebration (Classical Music)

Sunday, December 17, 2023

VOCES8: 'Jauchzet, frohlocket' by JS Bach

Thursday, June 15, 2023

The Widows of Bach, Mozart, and Mendelssohn: What Happened to Them?

by Emily E. Hogstad

However, historians tend to stop following the story once the composer dies. But have you ever wondered what happened to the composer’s families after their deaths? How did their widows keep their composer-husband’s music alive? And in eras before social safety nets, how did they survive…especially if they had kids?

Here’s what happened to three of classical music’s most famous widows after their husbands died:

Anna Magdalena Bach, 1701-1760. Married Bach in 1721.

Anna Magdalena Bach © www.bachueberbach.de

Anna Magdalena had just turned twenty when she married the widower J.S. Bach. In doing so, she became a very young stepmother to four surviving children, aged thirteen, eleven, seven, and three, all from his first marriage. Soon she began having biological children of her own. She would have thirteen in all, with seven dying very young.

When her husband died, Anna Magdalena Bach was forty-eight years old. She had been an accomplished professional singer in her youth, but she was in no position to restart her performing career…not to mention, she still had several minor children to raise!

Unfortunately, Bach hadn’t left enough money for them all to live on. She was left a portion of his estate, but J.S. Bach’s children, including his adult sons who were pursuing careers of their own, also got a cut of the assets, too. And alarmingly, the city of Leipzig only granted Anna Magdalena custody of her children on the condition that she not marry again, guaranteeing their future destitution.

Her stepson C.P.E. Bach was apparently the only child who stepped in to provide financial assistance, but it did not keep her from sinking into extreme poverty. She was evicted from her home and needed assistance from the city government to survive. She died a decade after her husband and was buried in an unmarked pauper’s grave.

Constanze Mozart, 1762-1842. Married Mozart in 1782.

Constanze Mozart

Mozart’s wife Constanze was twenty-nine years old when her husband fell ill and died, leaving her with two children, debts, and few prospects. She roused herself from her grief to line up support for herself, seeking out a pension from the emperor and organizing memorial concerts. She was a singer, and she put her musical abilities to use when she started publishing her dead husband’s works. Eventually, she grew to become a wealthy woman.

Six years after Wolfgang’s death, she took in a tenant named Georg Nikolaus von Nissen, a diplomat, and a writer. Romance blossomed. Rather scandalously, they moved in together the following year. They married in 1809, with von Nissen taking on the role of stepfather and helping Constanze with the administration and promotion of Mozart’s legacy.

Nissen’s last project was a Mozart biography, with which Constanze assisted. Nissen died before it was finished, but she made sure it was published, and it became an important source of Mozart lore. She lived in Salzburg along with two of her sisters, also widowed, and died in 1842 at the age of eighty.

Cécile Mendelssohn Bartholdy, 1817-1853. Married Mendelssohn in 1837.

Cécile Mendelssohn Bartholdy

Twenty-seven-year-old composer Felix Mendelssohn met nineteen-year-old singer Cécile Jeanrenaud in 1836 while he was conducting the Cecilia Choir in Frankfurt. They got engaged that September and were married in March 1837, and had five children together in Leipzig.

Unfortunately, tragedy hit the family in May 1847, when Felix’s beloved sister Fanny died suddenly and without warning of a stroke. Felix was deeply affected by her death, and he died in November 1847, also from a stroke. Cécile was only thirty.

Clara Schumann went to be with her and wrote: “She received me with the tenderness of a sister, wept in silence, and was calm and composed as ever. She thanked me for all the love and devotion I had shown to her Felix, grieved for me that I should have to mourn so faithful a friend, and spoke of the love with which Felix always had regarded me. Long we spoke of him; it comforted her, and she was loath for me to depart. She was most unpretentious in her sorrow, gentle, and resigned to live for the care and education of her children. She said God would help her, and surely her boys would have the inheritance of some of their father’s genius. There could not be a more worthy memory of him than the well-balanced, strong, and tender heart of this mourning widow.”

She kept her two daughters with her and sent her three sons to be raised by her in-laws in Berlin. Her son Felix died in 1851, compounding her grief, and she herself died of tuberculosis in 1853, leaving behind several children aged eight to fifteen.

Friday, May 19, 2023

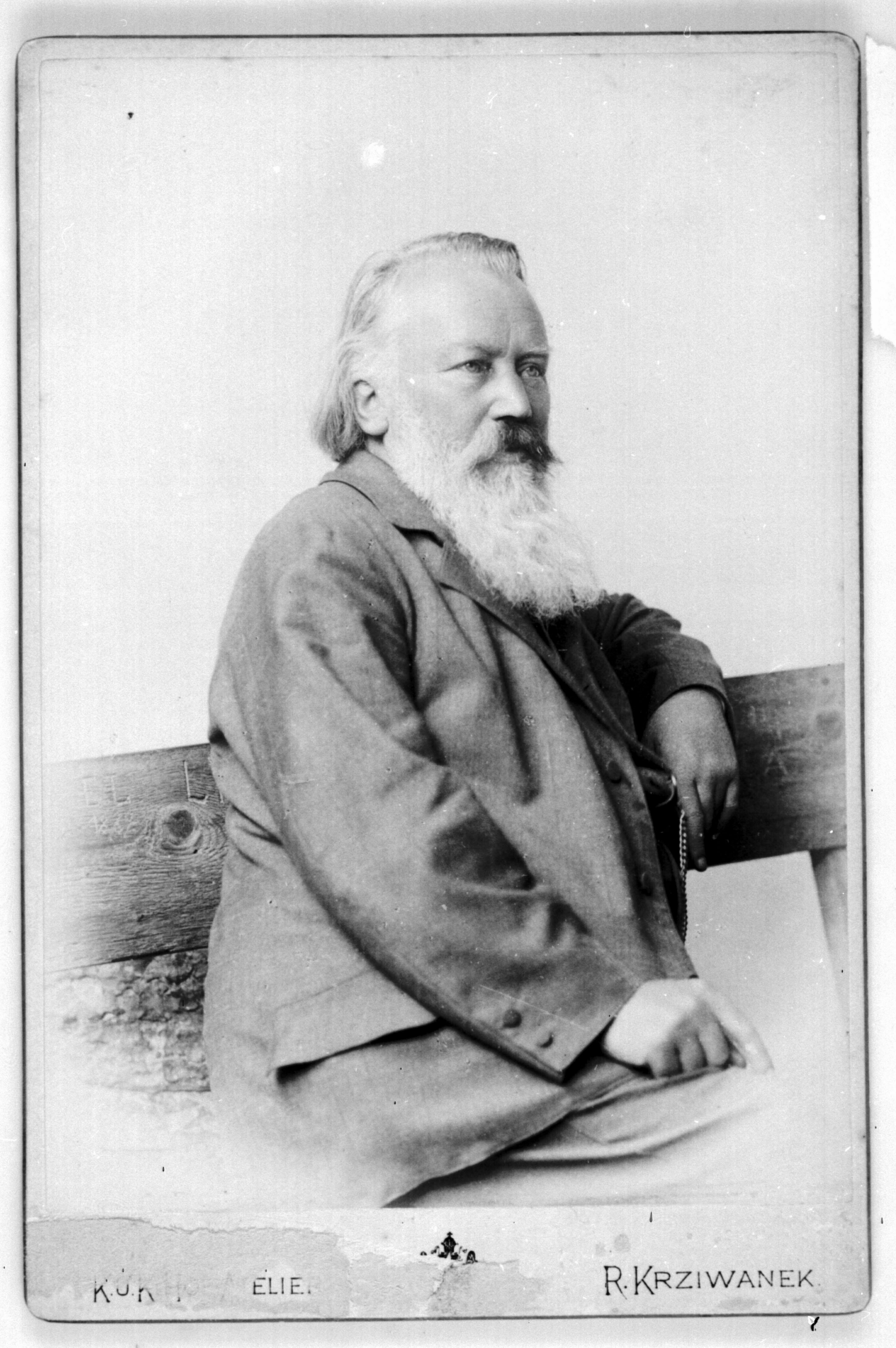

Brahms on the Road: A Trip to Transylvania with Piano and Violin I

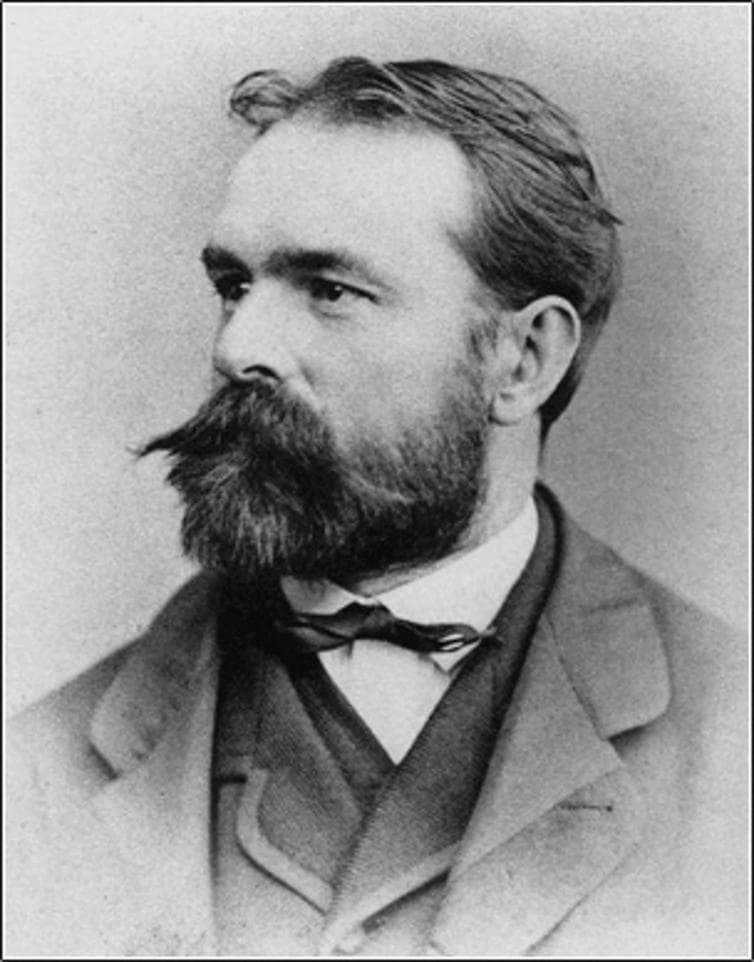

Johannes Brahms

In 1879, Brahms wrote to the librarian at the Gesesllschaft der Musikfreunde that he and the violinist Joseph Joachim were planning a tour to the extremes of the Austro-Hungarian Empire. Could he please send him, with the greatest urgency, some music by Beethoven, Schubert, and a bit of Schumann? Please have this in the mail two weeks ago! If the librarian couldn’t get these out of the library, please buy the Peters edition of the individual works requested and if those aren’t available, the complete violin sonatas of Beethoven and Schubert would do. Quickly!

Brahms was taking to the hinterlands with Joachim for a series of concerts. They were travelling deep into the Austro-Hungarian empire, to the middle of current-day Romania, which for the Viennese-living Brahms, would be like a New Yorker venturing into deepest Iowa.

For Brahms, this was a momentous decision: he hadn’t been on the road touring since the late 1860s when he needed the money, and when he was on tour, he complained about what the constant concertizing did to his fingers. Nonetheless, when Joachim’s agent suggested the tour as a way of combining music making with a holiday, Brahms was interested. Now that he was wealthier and could afford the leisure time, he could travel for the pleasure of it.

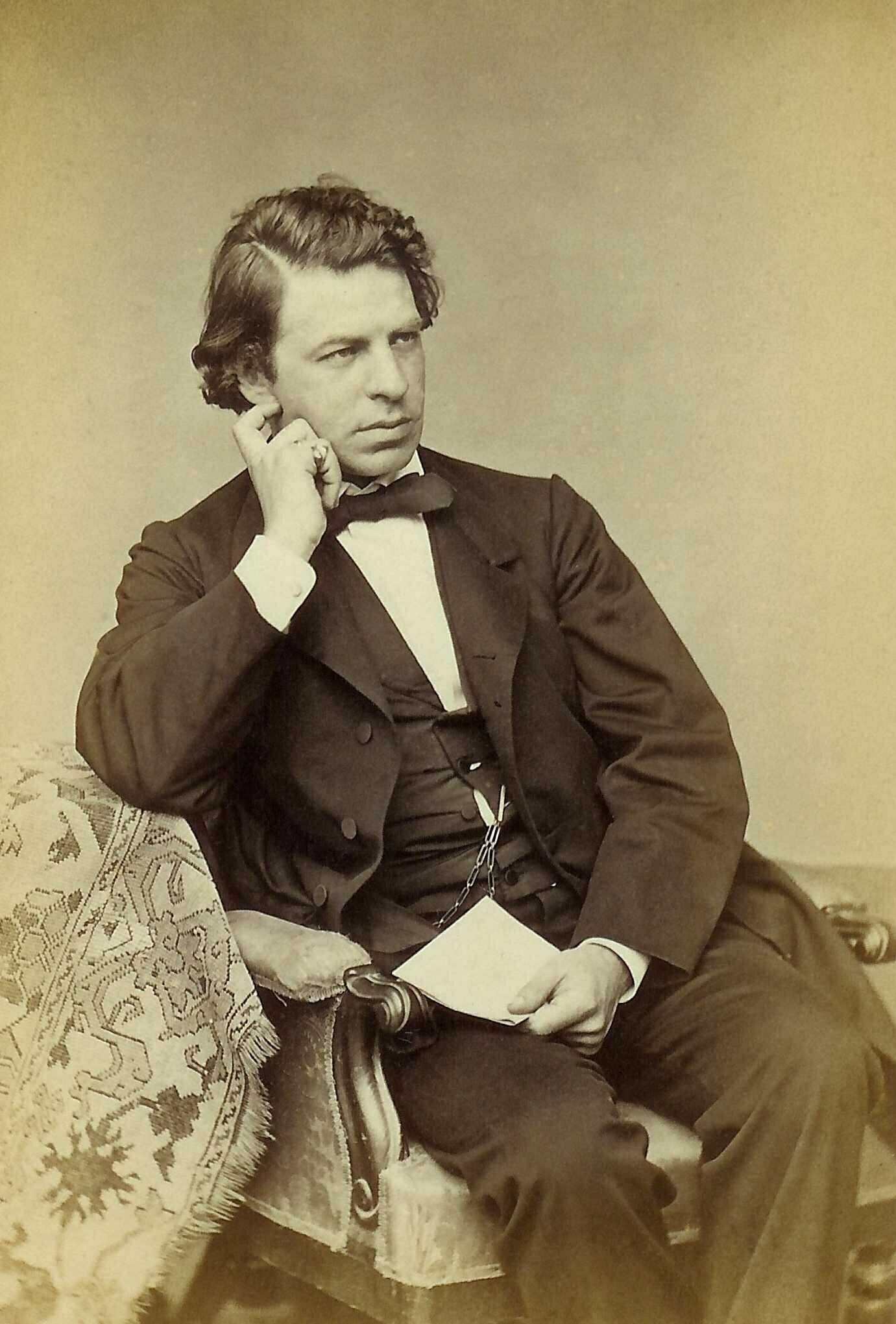

Joseph Joachim

It wasn’t easy to convince Brahms to go. Initially, he was reluctant, writing to his publisher Simrock that ‘…all concert tours…are a dubious pleasure.’ He said he wanted to travel in comfort and do some touring, but his concertizing companions, in the past, only wanted to do more and more concerts, scarcely lifting their eyes from the music to admire the scenery, and make money, of course. Eventually, though, he agreed and the tour was on.

Brahms and Joachim had only one day of rehearsal in Budapest, but then they were playing music that they probably knew from memory, having played it together for past quarter-century, with the one exception of a new work. The repertoire they travelled with included works from Bach to Brahms’ latest new work: the Violin Concerto, Op. 77. Joachim was the dedicatee of the work and had played its premiere, which hadn’t been a success. Joachim wanted to take it on the road as he needed to perform it more but Brahms wasn’t certain about reducing the orchestra to piano accompaniment alone. Joachim brought along Mendelssohn’s Violin Concerto as a backup, reminding Brahms that he had learned it from Mendelssohn himself.

The tour started on 13 September 1879 in Budapest, then by train to the city of Arad, just over the border in modern-day Romania. The next morning, off to Timişoara by carriage for a concert, return that night back to Arad, and then off to Sighişoara by train, concert the next day, and off the following day to Braşov. Back to the carriage for a trip to Sibiu, then onto Cluj, returning by train to Budapest on 24 September. This 11-day trip covered 1,600 km (1,000 miles).

The concert in Arad sold out almost immediately. The programme included Schumman’s Fantasiestücke for Piano and Violin (an arrangement of the Fantasiestücke for clarinet and piano), Tartini’s Devil’s Trill Sonata, and works by Bach, Beethoven, and Brahms.

Arad wasn’t quite as desolate and isolated as Brahms had imagined it to be in this tour of remote regions of the Empire. It was an important transportation hub, had a large military establishment, had the sixth music academy on the continent (opening only 11 years after the Royal Academy in London), and was a bustling commercial centre.

Reviewers noted in particular Brahms’ performance of the Schumann Novelletten, which seems to have been Brahms’ first performance of the entire work ever.

Off by single-track railroad to Timişoara, where the concert was promoted as presenting ‘The Piano Hero and the Violin King.’ The concert started with the Beethoven Violin Sonata, Op. 30, and closed with the Brahms Violin Concerto, Op. 77, arranged for violin and piano.

Finally, Brahms’ Violin Concerto was coming in for praise, with one reviewer calling it ‘one of the most important compositions today,’ but wished for an orchestra to accompany, rather than just a piano. Reports of the concert couldn’t understate their importance to the town: ‘anybody who was anyone, by birth, rank, position, anyone with an understanding for music, was present. They held their breath at the wonderful sounds of the Violin King and the rare virtuosity of Brahms, a pianist of the first rank. Stormy applause followed each number; the audience left highly satisfied, conscious of having been present at an evening of rare artistry.’

Friday, March 31, 2023

Musical Prayers for Peace

By Georg Predota

© National Today

In such times of deep political and ideological crisis, it is once again the musical community calling for an end to hostilities and musically praying for peace. And at the head of the class stands once more the celebrated cellist Yo-Yo Ma, appointed by the United Nations a “Messenger for Peace.” Yo-Yo Ma has been reaching out to people all over the globe, inspiring them to address the many challenging social issues we face today. In a recent concert with the New York Philharmonic, he performed a work that Pablo Casals often played to protest war and oppression.

Pablo Casals (1876-1973) was one of the greatest cellists of the twentieth century. He had to flee his native Spain in 1939 when dictator Francisco Franco took control at the end of the Spanish Civil War. Together with thousands of other refugees, Casals was housed in a refugee camp in France. “Casals spent much of his time delivering food and clothing to fellow refugees, and he continued to aid them throughout his life.”

Pablo Casals’ centenary statue

Yo-Yo Ma, at the age of sixteen, played in an orchestra under Casals’ direction. He recalls, “I never forget the way his mind and body would radiate vitality the moment he raised his baton… He saw himself not primarily as a cellist but as a musician, and even more as a member of the human race.” His personal anthem, “The Song of the Birds,” is a traditional Catalan Christmas song and lullaby, and after his exile in 1939, Casals would begin each of his concerts by playing his arrangement for cello.

It might come as a surprise, but the patriotic hymn “Prayer for Ukraine” dates back to 1885, and to a time when Ukrainian culture and language were once again suppressed by the government of Imperial Russia. It has been a very long struggle for independence for Ukraine, as different conquerors have mercilessly fought over this land rich in natural resources and culture. There was a short-lived revolution in 1919 brutally suppressed, and the Soviet occupation inflicted one tragedy after another.

Valentin Silvestrov

During the famine of the 1930s, millions of Ukrainian peasants starved to death because of the criminal policies of Joseph Stalin. The Nazi occupation of Western Ukraine saw the implementation of the “Final Solution,” first applied in cities whose wealth and cultural standing depended entirely on a vast Jewish population. And then there has been this perpetual tug of war over the Crimean Peninsula. Ethnic cleansing at the command of various Russian heads of State was repeated under Stalin, and then once again in 2014 after the Russian occupation. Instead of painting himself as a victim of Western aggression, Vladimir Putin and his shadow puppets should rightfully stand trial for committed war crimes at the International Criminal Court in The Hague.

On 23 February, Anatolii Vasylkovskii took the Ukrainian national chamber ensemble known as the Kyiv Soloists on a regular two-week tour to Italy. One day later, Russian troops invaded Ukraine, and he remembers, “When we arrived in Italy, many of our members phoned their families and heard that there had been bombings.” The focus of the tour changed in an instant, as “we had to spread the message that Ukrainians are peaceful people.” Relying on the solidarity of other ensembles and orchestras, who hosted them in their concert halls and homes, the tour was extended across Europe. Anatolii emphasized, “We want to dedicate these concerts to our families, our country, our army, which are now fighting for the democracy of the whole world.” The Kyiv Soloists want to convey a “message of peace and solidarity with the people of Ukraine and of love for the families and friends they have left behind.” Their performances are no longer simply aimed at cultural exchange and musical enjoyment; they are a form of activism. “Our music-making is now a prayer for peace.”

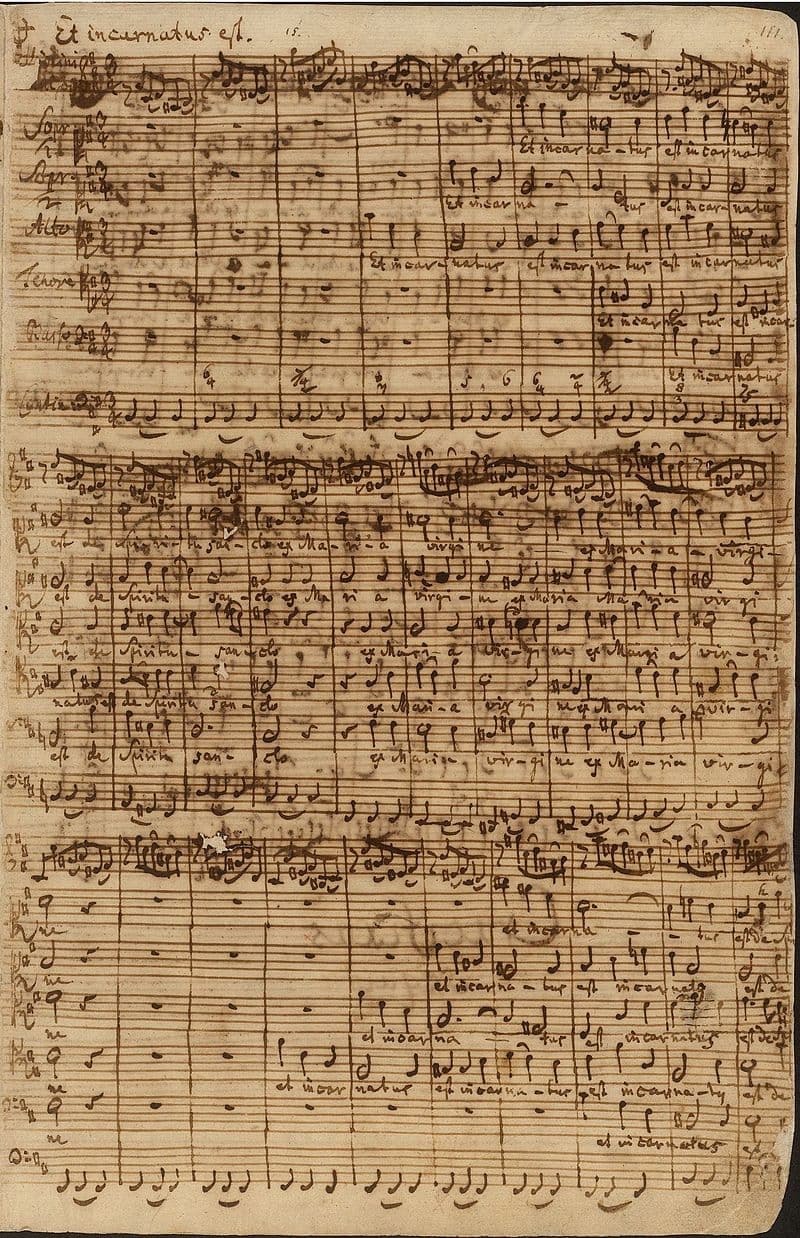

If I may be permitted, let me add my personal musical prayer for peace by turning to the music of Johann Sebastian Bach. In 1817, a critic called Bach’s Mass in B minor “the greatest work of music in all ages and of all people.”

Bach’s B minor Mass, BWV 232

While this kind of assessment might need a bit of clarification, the work is significant because we find a Lutheran composer setting the complete Latin text of the Catholic Mass Ordinary. So, how does a devout Lutheran musically deal with the line in the Creed, “and I believe one holy catholic and apostolic Church?” That particular text receives two melodies sung by the choir simultaneously, and in perfect harmony. One is the traditional melody sung by Roman Catholics, and the other is a Lutheran chorale melody. The language of music, after all, has the distinct ability to console and unite. Let us now join the Bach Collegium Japan in Bach’s short prayer for peace, the “Dona Nobis Pacem” (Grant us Peace) from his B-minor Mass.

Friday, January 6, 2023

Musical Double Takes: Bach, Bentzon, Czerny, Rekhin, Rheinberger, and Madsen

by Georg Predota, Interlude

Johann Sebastian Bach

Score of Bach’s Well-Tempered Clavier

The Well-Tempered Clavier, Book I, and the Well-Tempered Clavier, Book II are rightfully considered among the most important works in the history of Western music. These works have been highly influential, and various composers have composed complete sets. However, I want to introduce you to composers, who like Bach, did a musical double take and composed multiple sets of preludes and/or fugues in all keys.

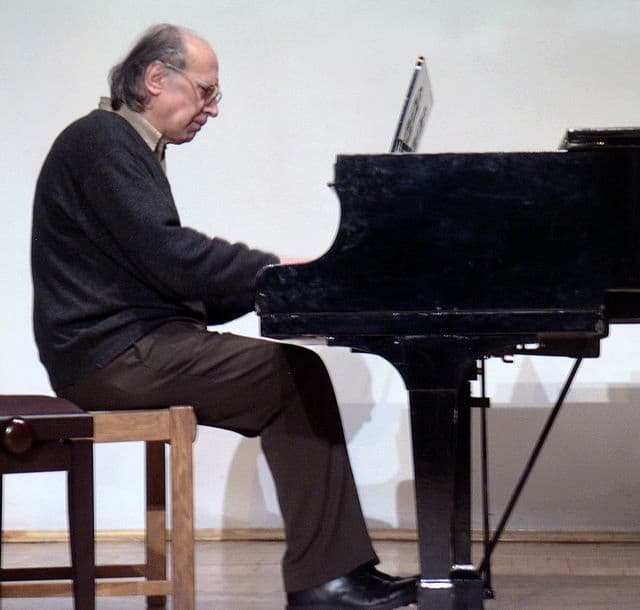

Johann Sebastian Bach amazingly wrote two complete sets of preludes and fugues, but the Danish composer and pianist Niels Viggo Bentzon (1919-2000) composed 14 separate sets of 24 preludes and fugues! By any stretch of the imagination, that is an astonishing number of works. They are collectively known as “The Tempered Piano,” and represent 20th-century examples of music written in all 24 major and minor keys.

Niels Viggo Bentzon

Niels Viggo Bentzon

In an interview, the composer referred to his “Tempered Piano as a series of aesthetic paradoxes. By this, I mean an almost complete transcription of the building blocks of classical music. If a Fugue from one of the tempered pianos is crammed with imitation, one can be dead sure that the phenomenon functions differently than in Bach or Handel. In The Tempered Piano, a theme may appear in its entirety at the beginning of the piece, only to change gradually, almost out of recognition, as that particular piece winds to an end.” The composer was once asked about the exact meaning of his compositions, and he responded, “I have to admit with shame that I am virtually seldom inspired. It is just a matter of getting hold of a pencil and firing away.” Bentzon has also composed 24 Symphonies—not ordered according to keys—operas, ballets, concertos, string quartets, and many additional piano works.

Carl Czerny (1791-1857) came from a very musical family. His grandfather was a professional violinist, and his father an oboist, organist, and pianist. Little Carl was a child prodigy, and he started piano lessons with his father at the age of three. By the age of ten, he became a student of Beethoven, and he maintained a relationship with the composer throughout his life. At the core of Carl Czerny’s early piano studies stood Bach’s Well-Tempered Clavier. We know that he carefully studied this collection during his early lessons with his father. Likewise, the WTC had been fundamental to Beethoven as well.

Carl Czerny

Carl Czerny, 1833

Today we know that Czerny produced a collection of exercises and studies that might rightfully be described as “industrial.” He composed a number of fugues early on that became part of his performing repertoire as a concert pianist. Czerny composed at least three complete sets of preludes and fugues in all 24 major and minor keys. The most impressive collection emerges in his Op. 856, in which he tried to update this archaic genre. It has been suggested that Czerny dedicated this set to Liszt, who had been Czerny’s most outstanding student. We don’t know how Liszt reacted to the dedication, but critics were generally dismissive. Robert Schumann “accused Czerny of insisting on an obsolete genre without renewing in any way the classical models established by Bach.” He even found fault with Czerny’s creativity, with the way he avoided the formal procedures that make the fugue interesting: transformations of the subject through augmentation, diminution, inversion, crab canons, and layering two or more themes or using subject and countersubject in the Handel fashion. Although homages to Bach and Handel are frequent, Czerny does attempt to dress his use of strict counterpoint in the characteristics of the emerging gallant style.

Igor Rekhin

Igor Rekhin

Collections of preludes and fugues in all major and minor keys are not exclusively tied to keyboard instruments. Such is the case with Russian composer Igor Rekhin, born in 1941. Rekhin fashioned two complete sets: the 24 Caprices for solo cello, and 24 Preludes and Fugues for guitar. Rekhin composed over 100 works in various genres, but the 24 Preludes and Fugues for solo guitar are unique. The initial idea emerged in 1985, on the 300th anniversary of Bach’s birth. The composer writes, “At the beginning of the work on the prelude and fugue I imagined a musical idea that I subsequently wrote down. I tested that idea on the piano and then elaborated it on the guitar. I quickly found that many ideas that sounded good on the piano were difficult to transplant to the guitar. That path was ineffective, so I changed my approach and just picked up the guitar and began to look for polyphonic solutions.” Critics were enthusiastic, and suggested that the collection “opened the concert repertoire for guitar in a completely new way. Maintaining the tradition of the old polyphonic masters of the lute in a homogeneous connection with the latest styles and trends, including pop to avant-garde, this cycle gives guitarists the opportunity to be placed on par with other traditional concert instruments such as the piano.”

Josef Rheinberger

Joseph Gabriel Rheinberger

Joseph Gabriel Rheinberger (1839-1901) was born in Liechtenstein, and he inherited his musical talents from his mother. He started lessons with the local organist at age five, and two years later he was appointed organist in Vaduz and was writing his first compositions. Against the wishes of his family, Rheinberger went to Munich to continue his studies, and he subsequently held a number of important posts in that city. Among them was the appointment as the instructor in counterpoint at the Royal Academy of Music, and his students included Engelbert Humperdinck, Ermanno Wolf-Ferrari, and Wilhelm Furtwangler. Organ music formed the core of Rheinberger’s compositional efforts, and he espoused a conservative musical style influenced by Bach, Mozart, and Haydn. As such, it is hardly surprising to find two sets of compositions in all major and minor keys. His 24 Fughettas Op. 123 are essentially lyric miniatures in a highly contrapuntal style. Rheinberger was also looking to compose 24 organ sonatas in all major and minor keys but sadly died having completed only 20.

Trygve Madsen

Trygve Madsen

The Norwegian composer Trygve Madsen was born in 1940. “I had the good fortune to be born into a family of musicians,” he explains, “my grandfather and his seven sons were all professional musicians. At six I began playing the piano and began composing at about the same age. As my piano playing developed I became increasingly involved in the daily music-making at home, joining in anything from popular songs to sonatas.” Madsen studied with the organist Johannes Almgren, who had been a student of the famous theoretician Hermann Grabner, who in turn had been a student of Max Reger. However, Madsen was not only interested in counterpoint but from an early age, he was also attracted by jazz. He listened to recordings by Erroll Garner, Dizzy Gillespie, Charlie Parker, and Oscar Peterson for hours on end. A clear formative musical influence was provided by Sergei Prokofiev, with Madsen writing ”That was what made me a composer. I realized that this was the way for me; everything came together in Prokofiev’s music. It was like coming home! Prokofiev shaped and molded his musical material in his own way with superb craftsmanship, without violating the rules of music – often infusing it with a liberating sense of humour.” Madsen composed two complete sets of music in all major and minor keys; 24 Preludes, Op. 20 and 24 Preludes and Fugues, Op. 101. He began work on the full cycle of 24 Preludes and Fugues in 1995, with a clearly laid out play of the order in which the keys would be presented. Bach had ordered his set chromatically, while Shostakovich and Chopin preferred an order according to the cycle of fifths. Madsen, ingeniously, based his collection on the astrological treatise “The Harmony of the Spheres,” by the German astronomer Johannes Kepler. Kepler suggested, “the relationship between the planets corresponds to the relationship between musical intervals.” Basing his set on an astrological point of view, Madsen’s system “consists of a row of descending minor thirds interrupted by an ascending tritone. In the next episode of musical double takes, we find music by Charles-Valentin Alkan, Lera Auerbach, Adolf von Henselt, Vsevolod Zaderatsky, Dmitry Shostakovich, Johann Nepomuk Hummel, Louis Vierne, Friedrich Kalkbrenner, and Nikolai Kapustin.